Part of a series of articles titled Badlands Geology and Paleontology.

Previous: The Big Pig Dig

Article

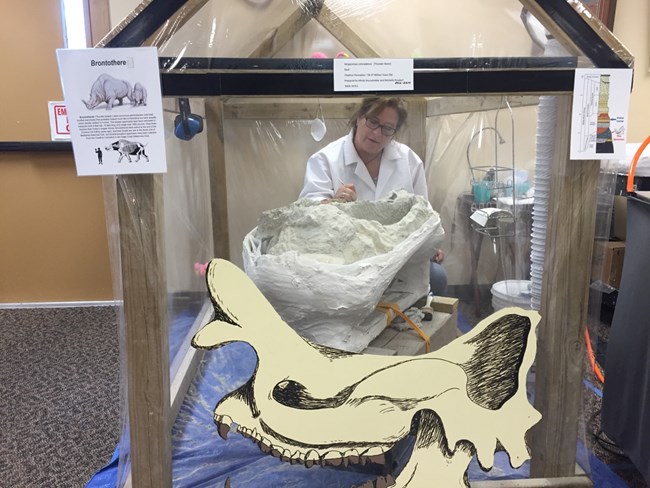

NPS Photo

A brontothere is an ancient mammal which roamed the area of Badlands National Park about 38-34 million years ago. Badlands brontotheres are also known as Megacerops coloradensis in scientific literature. Sometimes called “titanothere,” its name means “thunder beast,” referring to how a traveling herd of massive brontotheres may have sounded long ago, thundering through ancient environments .

Brontotheres found in the Badlands would have measured around 8 feet tall and 16 feet long, the size of a large rhino or small elephant today, but brontotheres began as only dog-size animals in the early Eocene epoch. Over the next 20 million years of the Eocene, brontotheres became larger as they evolved and diversified. By the late Eocene, brontotheres reached the massive size we see in Badlands fossil brontotheres today.

Brontotheres are usually known for the blunt paired horns which stuck out from their noses. These horns developed from small nubs into the giant horns that stretch over 3.3 feet (1 meter) long in Badlands brontotheres. Horns tend to be larger in males and smaller in females. Although these horns usually inspire thoughts of rhinos, brontotheres are related to modern rhines. Even so, Badlands fossils include animals like Subhyracodon, which are true ancestors of the modern rhinomembers of the rhino family!

The knowledge of these “thunder beasts” existed long before American paleontologists came to understand them. Though Othniel Charles Marsh coined the name Brontotherium, or “thunder beast”, he was inspired by Lakota oral histories of giant beings involved with violent thunderstorms. Marsh first heard about thunder being remains in the Badlands from James Cook, who would later homestead on and preserve the Agate Fossil Beds. Cook was great friends with several Lakota leaders who shared the stories, such as Chief Red Cloud, Little Wound, and American Horse. Cook was shown a jawbone with a tooth collected by Young Man Afraid of His Horses, who would later show Marsh. Cook introduced Marsh to Chief Red Cloud, and the two became good friends for the rest of their lives. Red Cloud even visited his friend Marsh at Yale University.

Original artwork “Subtropical South Dakota, Chadron Formation, Badlands National Park” commissioned by Badlands Natural History Association and painted by Laura Cunningham © 2005.

Brontotheres inhabited the lush forests of the Eocene epoch. These forests appear in the Badlands rock record as the Chadron Formation, which is where the park’s brontothere fossils are found. Brontotheres were herbivores, meaning that they survived by eating plants instead of other animals. Brontothere teeth are low and flat, which are good for grinding up vegetation. Studies examining the wear on brontothere teeth have found that brontotheres most likely ate the soft leaves found in Eocene forests.

The purpose of brontothere horns has been speculated about over time. Initially, some scientists believed that brontothere horns would have been employed in head-on collisions like those of bighorn sheep today. As paleontologists considered this hypothesis, they concluded that it wasn’t possible: the base of brontothere bones is too thin and spongy, it would have broken easily under such an impact. Instead, scientists now propose that brontotheres used their massive horns for wrestling, head-to-head pushing, and swinging – if they used their horns to hit each other, the impacts would have been side-to-side, not head-on. The purpose of these movements may have ranged from toppling one another over to protecting brontothere calves from predators.

Brontotheres went extinct at the end of the Eocene epoch (about 34 million years ago) alongside other fossil mammals. Although the reasons for this extinction are not completely known, it is likely due to a changing climate. The climate shifts from hot, wet, and lush in the Eocene to cooler and drier in the early Oligocene.

When the climate shifted, so did the environment: humid forests of the Eocene became the dry scrublands of the Oligocene. The change in vegetation type resulted in major changes for herbivores. Animals which could adapt to drier, hardier plants such as early grasses went on to prosper and continued evolving. One example of these animals is Mesohippus, the ancestor of the modern-day horse. Animals with low-crowned teeth designed for the soft vegetation of Eocene forests, like brontothere, struggled to eat the harder forage available.

With no soft leaves to munch on, brontotheres died out alongside other herbivores which couldn’t adapt to changing vegetation. Although they died out around 34 million years ago, brontotheres would still leave a legacy in the American paleontological record – no larger mammal inhabited North America until millions of years later, when the first mastodonts (mammoths) roamed the continent.

NPS Photo

Brontothere was one of the first fossil mammals discovered west of the Mississippi. The first brontothere was discovered in 1846, found in the Badlands 70 years before the National Park Service was founded. Combined with other finds, this brontothere led to one of the first “bone rushes,” in which the discovery of fossils and geological structures drew scientists to the American West. Scientists were collecting fossils all over the Midwest, and many went to the Badlands, already well-known for its abundance of fossil mammals.

But brontotheres continued playing a starring role in the Badlands, even after the bone rushes of the 19th century were over. In the 1940s, the US Air Force took possession of 341,726 acres of land from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation (337 acres of which were located on then Badlands National Monument) for use as an aerial gunnery range. Among old car bodies and 55-gallon drums painted yellow, gleaming white (and enormous) brontothere skulls were visible from the air and used as target practice by USAF bombers. The Badlands, and the science of paleontology, lost hundreds of fossil resources in the process.

Part of a series of articles titled Badlands Geology and Paleontology.

Previous: The Big Pig Dig

Last updated: November 10, 2020