Black and On March 18, 1911, President Theodore Roosevelt traveled by automobile parade through the rugged Arizona terrain to dedicate Roosevelt Dam. A crowd of nearly 1,000 followed in the dust, eager to witness their “Teddy” dedicate the great dam, built to store water that would, in time, transform desert soil into fertile farmland and little Phoenix into an urban center. Completion of the dam inspired a song that praised the President who championed the reclamation of Arizona’s sunny valley. It chimed,

“If you miss me when the blizzards blow, then you’ll know where I am/ And you can join me down in Phoenix where Teddy built the dam.”

The dam—and later, its hydroelectric powerplant—brought stability and hope to Arizona, as part of the Federal Government’s new Salt River Project that reclaimed more land for farmers and, for the first time, brought electric power to area homes. Standing on the crest of the massive dam named in his honor, Roosevelt proclaimed the 1902 Reclamation Act, along with the Panama Canal, as his administration’s top achievement.

Water was always key to habitation in the harsh desert of the 12,000-square-mile Salt River basin. Named for its brackish waters, the Salt River begins high in the White Mountains of eastern Arizona and flows southwesterly for more than 200 miles, converging with the Gila River just west of Phoenix. The basin once was home to the Hohokam people who, beginning in about 300 A.D., dug a sophisticated network of canals and ditches, and farmed the valley for centuries. Mysteriously, the Hohokam culture vanished around 1450 A.D. Then, the Pima and the Maricopa Indians farmed the area using irrigation. In the late 1600s, Spanish priests arrived, exerting their energy in mission work, but also in irrigating their gardens with the construction of acequias, or community ditches.

The end of the Mexican War in 1848 brought the Salt River basin into United States control. American settlement increased with the Civil War’s end in 1865. In 1867, Civil War veteran John W. “Jack” Swilling created the Swilling Irrigation and Canal Company, and in 1868 he and his partners dug the Salt River Valley Canal and established “Phoenix” on the ancient lands of the Hohokam. By 1870, Phoenix counted 200 people farming 3,000 irrigated acres planted in wheat, barley, and corn. Expanded ditch networks and the new railroad line helped Phoenix grow, but the unpredictable Salt River—which sometimes raged with uncontrollable torrents and other times held a mere trickle–hampered full development of the Salt River Valley’s agricultural potential.

After devastating droughts in the 1890s, farmers pursued ambitious plans to build a dam in the mountains to capture the spring floods, which would both help protect their diversion dams from being washed away and would store water for summer use. However they failed to raise enough money. In 1903, they formed the Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association, got the attention of President Teddy Roosevelt, and campaigned for Federal aid. In 1903, Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock approved the Salt River Project as one of a group of five reclamation projects first authorized for construction by the newly created United States Reclamation Service.

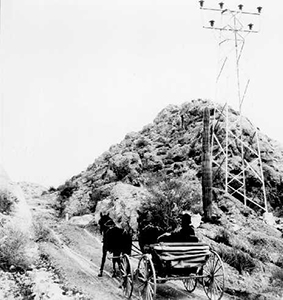

The Salt River Project’s Roosevelt Dam was an impressive feat of engineering for the fledgling Reclamation Service, especially considering its location some 60 miles from the railhead at Mesa City. So remote was the site of the dam that transporting construction materials was the first obstacle to overcome. To reach the canyon damsite, construction crews, some composed of Apache Indians, built the Mesa-Roosevelt Road—soon known as the Apache Trail—through the harsh terrain, then hauled materials in by mule teams. To reduce the amount of fuel oil that crews constantly hauled to the damsite, Arthur Powell Davis, Chief of the Division of Hydrography of the U. S. Geological Survey and later Director of the U.S. Reclamation Service, recommended constructing a temporary hydropower plant to generate electricity onsite.

Starting in 1904, Reclamation contracted for the construction of a 19-mile-long canal that, with the help of a diversion dam, channeled water to power a little powerplant, which was located in a shallow cave within the canyon wall just south of and below the damsite. The current generated there powered the drilling, mixing, and crushing of rock for concrete.

In June 1909, the permanent Roosevelt Powerplant entered service, replacing the temporary plant. Abutting the canyon wall just below Roosevelt Dam, the plant was built of the same dolomite limestone—sometimes confused with sandstone—as the dam. Inside were three constant-head vertical hydraulic turbines and three 1000 kilowatt vertical generators. By August 1909, all three units were online and water from the reservoir poured in to spin the turbines, creating electricity. From the powerplant, electricity went to the transformer house, 600 feet downstream from the power plant, where the original 2,300 volts were stepped up to 45,000 volts for long-distance transmission to the dam site and beyond to the Salt River Valley, establishing the Salt River Project as one of Reclamation’s first projects to not only provide water for irrigation, but also electricity.

Reclamation’s own hydroelectric power also helped build Roosevelt Dam. Completed in 1911, the dam contained 344,000 cubic yards of masonry and stood 280 feet high—at the time the tallest stone-masonry dam in the world. Behind Roosevelt Dam rose Roosevelt Lake, with a capacity of more than a million acre feet of water, enough to irrigate the Salt River Valley farms for more than 4 years without replenishment. By 1916, Roosevelt Powerplant housed six dynamos, generating electricity that surged throughout a 208-mile grid of transmission and distribution wires. The current powered nine pumping plants that irrigated nearly 10,000 acres. In 1917, as always planned, Reclamation transferred operations to the Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association, but maintained ownership of the properties.

World War I boosted industry and agriculture in Arizona, which then raised demand for electric power. Association management developed plans to increase power generation on the Salt River Project to make money to pay project debt. The plans sparked controversy between the Water Users’ Association management and its members, because water stored in Roosevelt Lake could only be released for irrigation between April 1 and October 1. Some users feared their irrigation water would be spent for power production, but Frank Reid, the Association president, declared, “We are in the power business.”

Finding common ground, and after receiving Reclamation’s approval, the Association constructed three additional storage dams with powerplants—Horse Mesa Dam, Mormon Flat Dam, and Stewart Mountain Dam—all downstream from Roosevelt Dam, creating a 60-mile series of reservoirs. From dam to dam, water stepped down the river, was released for power generation at each stop, then recaptured for irrigation. Reclamation was allowed to release project water only for irrigation purposes, so the Association would have to build a dam downstream that could recapture irrigation water released for hydropower purposes.

Between 1902 and 1935, Phoenix’s population mushroomed from 5,000 to 35,000, while the Roosevelt Powerplant labored at nearly 100 percent increased capacity since its original construction. In September 1924, following a campaign by the Water Users’ Association, Reclamation added seventh and eighth units to the powerplant. To accommodate the new systems, crews added an additional story to the front of the plant and two stories to the back, which allowed all eight units and the transformers to be housed in the same building.

In the early 1970s, a new generator and turbine unit and transformer were installed in front of the original Roosevelt Powerplant, leaving only its second and third stories, including its original horizontal molding, clearly visible. In the 1980s and 1990s, Roosevelt Dam was made higher to increase flood control storage capacity. The original masonry dam was enclosed in concrete, drastically changing its appearance. While today the dam that Teddy built sits encased within a concrete veneer, and the powerplant has had several additions, their legacies speak to Roosevelt’s belief that water resources of the American West were important to the future of the United States. Although the Phoenix basin has grown into an urban center – today it is the nation’s sixth largest city – agriculture, not power production, remains the priority purpose of the Salt River Project.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017