Courtesy of the Indiana University Archives, Bloomington Indiana.

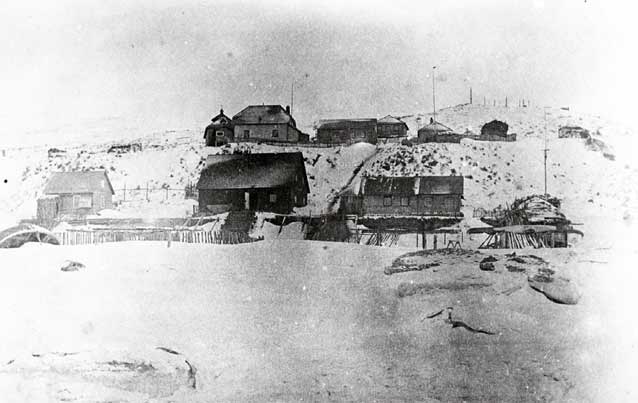

During the late 1870s and early 1880s, the U.S. Signal Service became the leading federal agency responsible for compiling meteorological data in Alaska. General William B. Hazen, chief signal officer, collaborated with Spencer F. Baird, assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, in selecting young naturalists to gather data at meteorological-natural history stations. Stations were established at St. Michael, Unalaska, and Nushagak. Perhaps the most accomplished Signal Service agent was Edward Nelson, who was stationed at St. Michael between 1877 and 1881 (Unrau 1992).

On March 2, 1881, Baird wrote to David Starr Jordan, a professor at Indiana University, telling him of a great opportunity for “some earnest student of natural history to acquire distinction,” by documenting a “vast region now unknown,” to the wider world. Baird was “anxious to find a first-rate man to go as signal observer to Bristol Bay, in Alaska . . . the best locality for zoological discovery in North America . . . The ethnological field is also one of wonderful richness, furnishing an opportunity for important discoveries & collections of all kinds can be made in vast amounts.” (Baird 1881).

The duties assigned to the observer at Nushagak were stated in a letter of March 22, 1884, by Baird to James W. Johnson, the second observer at that post. “Your primary duty at the station will be to make twice-daily observations in regard to the thermometer, barometer, rain gauge and next to that, to make collections of specimens of natural history and ethnology for the National Museum.” The observer was also authorized to make purchases of trading stock from John Clark at the Alaska Commercial Company post, such as tea, sugar, pilot bread, and tobacco to barter with Natives for various artifacts and services such as guiding and paddling baidarkas on collecting trips (Baird 1884).

Courtesy of the Field Museum, 283410.

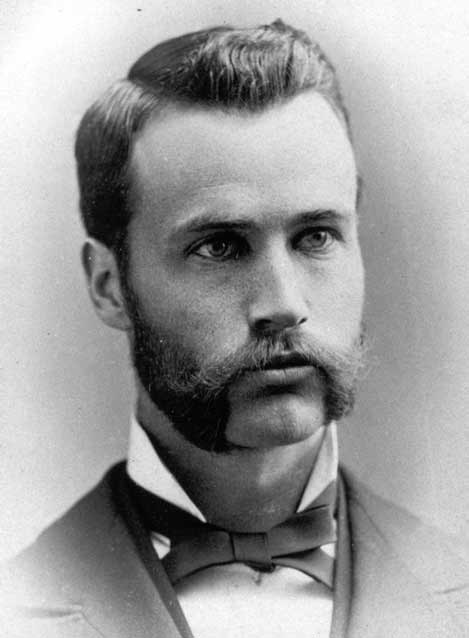

The first Signal Service observer at Nushagak was Charles Leslie McKay. He was born near Appleton, Wisconsin, on April 21, 1855. At a young age, McKay did chores on the family farm and demonstrated a great love of the natural world, in particular birds and fish. He enrolled in the Appleton Collegiate Institute and became a student of David Starr Jordan. When McKay wanted to become a naturalist like Jordan, he first went to college at Cornell University. In the late 1870s, McKay followed his mentor, Jordan, to Butler University and transferred again to Indiana University, where he was graduated in 1881 (Mearns 1993).

For a short time during the winter of 1881, McKay worked for the U.S. Fish Commission in Washington, D.C., where he must have come to the attention of Baird. By late winter, he had been selected to man the Signal Service station at Nushagak. McKay enlisted in the Signal Service on March 28, 1881, as a private. McKay sailed from San Francisco to Nushagak that spring.

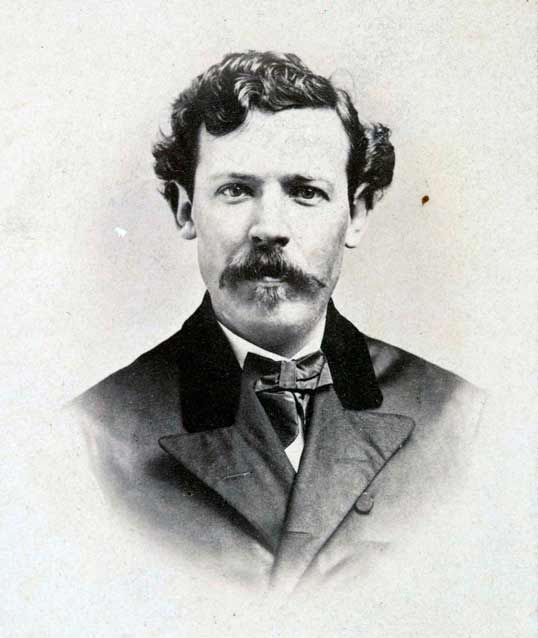

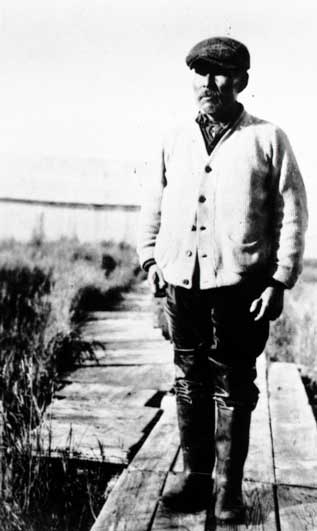

McKay arrived at Nushagak in June, where he met Clark. Clark was an experienced Alaska hand, having been in Alaska since the late Russian America period. Clark was to be McKay’s only English-speaking companion for the next two years. McKay lived in a small log house next to Clark’s Alaska Commercial Company store. Twenty years later, biologist Wilfred Osgood, the second federal biologist to work in the Bristol Bay region, stayed in the same house (Osgood 1904).

Clark would become McKay’s translator and chief local informant, sharing his knowledge of the Bristol Bay people and the locations of various natural and cultural resources suitable for museum collections. One immediate need Clark resolved was hiring local Yup’ik guides with their three-hatch baidarkas to take McKay on collecting forays around the Bristol Bay region. The pay would probably have been in trade goods, such as tea, tobacco, or gun powder. Clark loaned his own kayak to McKay, and soon McKay wrote to Baird at the Smithsonian of his need of a skin boat: “I will get a baidarka for my own use this coming season. I have been using one of the Company’s baidarkas, but I cannot always have it when I want it and it sometimes puts Mr. Clark to inconvenience. It would probably cost about $15.” (Baird 1881).

Courtesy of Dennis and Lois Herrmann

McKay began collecting as soon as he arrived at Nushagak village, Osgood wrote in A Biological Reconnaissance of the Base of the Alaska Peninsula (Osgood 1904); he collected a fox sparrow on June 6, 1881. McKay wrote in July 1881 that he went to the head of Bristol Bay. By that, he seems to have meant to the mouth of the Kvichak River. McKay went as far south as the Ugashik River, where he collected ethnographic specimens, including an elaborately beaded headdress (Fitzhugh and Crowell 1992). McKay hoped to go on a collecting trip to the northward of Cape Constantine, an area that was rocky (Kulukuk and Togiak) “if the weather quiets down sufficiently this fall.” It is doubtful that he ever traveled to Togiak himself, yet he might have collected specimens from that location with the aid of a Togiak resident who ran a small trading station for Clark (Baird 1881).

In the mid- to late-19th century, travel was difficult at best in Bristol Bay country. When the Bering Sea and the inland waters were ice-free, travel was by kayak, baidarka, or baidara. Winter travel was by dog team and was generally less laborious than travel by skin boat, yet, it too, was very physically demanding.

McKay wrote that he had “a smart young fellow . . . one of the agents of this company Alaska Commercial Company collecting for me on the other side of the bay.” Unlike the better-known Signal Service agent Edward Nelson, McKay’s few extant letters are often vague about locations and dates. He might have been referring to Togiak, Egegik, Ugashik, or Koggiung villages or even Igushik, west across Nushagak Bay from his home at Nushagak (Baird 1881).

McKay was a skilled collector, and he was able to establish a level of trust and mutual respect with Bristol Bay Natives, which enabled him to do his job of collecting natural history specimens. That would be borne out by the fact that he traveled widely in the Bristol Bay drainage collecting artifacts and specimens with Native guides and paddlers. Some of the locations he visited were Lake Aleknagik, Igushik, Ugashik, Kvichak Bay, Iliamna Lake, Lake Clark, and the Chulitna Portage, including the Swan, Koktuli, Mulchatna, and Nushagak Rivers (Osgood 1904).

Osgood is the best source for information on the extent of McKay’s travels around much of the Bristol Bay region for several reasons. In 1902, for his wide-ranging trip around the bay, Osgood hired the same Dena’ina guide as McKay, Zackar Evanoff. Evanoff had guided McKay on the same portage from Lake Clark to the Nushagak drainage. In addition, when writing his book, Osgood had access to McKay’s field notebooks to document locations of where the collections were made.

Courtesy of the Elizabeth Butkovich Collection

McKay did write his friends in Indiana telling them of some of his adventures, and it is clear that he also traveled by dog sled from Nushagak during the winters of 1881-1882 and 1882-1883. David Starr Jordan references the last letter McKay wrote to Spencer Baird on January 26. Osgood established that McKay went upriver during the spring-summer of 1882. It seems inexplicable that McKay did not write a lengthy letter to Baird detailing his collecting trip to the Chigmit Mountains. Yet no such letter exists in the Smithsonian Institution Archives. It seems likely, though, given that McKay wrote to Baird on January 26, 1882, describing his intention of going to the Chigmits:

There is one section of this district, up at the head of this river [Nushagak River], among the Chigmit Mountains and inland, that is entirely unexplored and unknown. No white man has ever been there. It is very probable that many species of birds that are not found here will be found there . . . The mountain sheep and little ‘chief hare’ pika are very abundant there, but it is impossible to get the Natives that live around here to kill the latter as they have some superstition about it. The Natives also say that there is a goat that lives in these mountains . . . I have no doubt that if I could spend one summer in that region, I could do good work there. Looking towards that end, I have a proposition to make . . . Mr. Swain, who has been at work in Professor Jordan’s laboratory remarked incidentally in one of his letters that he ‘wouldn’t mind spending a year with me.’ If he would come, I could leave my station in his charge. The expense to the Smithsonian would only include his transportation to San Francisco and return . . . In that case, I would, of course, be without salary, but I would be perfectly satisfied with having my traveling expenses paid . . . Mr. Swain would be a very valuable aid in developing the resources of this large region. There is yet a good deal of work to do and I do not care to return under four years. (Jordan 1883).

Osgood was certain that McKay did reach Lake Clark, and there are several specimens in the Smithsonian’s American Museum of Natural History collections attributed to McKay from the Chulitna River, a tributary of Lake Clark. Moreover, Osgood states that his guide in 1902 on the Chulitna River was Zackar. “He [McKay] also made a trip over a considerable part of the route traveled by our party,” Osgood wrote. “He visited Lake Iliamna and Iliamna Village, and according to an account received from a Native, [Zackar] crossed the Chulitna Portage. By strange coincidence, the same Native who, as a young man accompanied McKay on his trip, went with us from Lake Clark to Swan Lake, and related to us various incidents of the trip made twenty years before, [with McKay] . . . our guide, Zackar, a very intelligent Native from Kijik village.” (Osgood 1904).

Courtesy of Sandra Orris and the NPS.

McKay wrote another intriguing letter from Nushagak on April 14, 1882, to an unnamed friend at his alma mater, Indiana University:

In Nushagak here, they [Natives] have adopted the European dress to a greater extent than anywhere else in the Bristol Bay region, but they still retain the parka and the moccasins or skin boots. As you go inland, however, the people dress entirely in skins. Their dishes and weapons of the chase are made just as their forefathers made them . . . The Indians of the interior . . . There is a tribe of them, living up on the Molchatria [sic] River, a branch of the Nushagak River . . . They were far more sociable than these [Yup’ik ?] people, as far as my observation went—different in features and language. In Callogamuck [Koliganak] I saw one huge squaw [sic] with a face as big and round and expressive as the full moon. (McKay 1882).

McKay’s Bristol Bay life was described by the editor of The Indiana Student:

If space permitted, we should be glad to add many other interesting extracts from Mr. McKay’s long and interesting letter. His experiences in that strange far-away land, with fish, fowl, men and ferocious mammals, among mountains and fleas, and in the wilderness with spruce boughs for a bed, the sky for a coverlet, and a thermometer marking 29 below zero for a bed-fellow, are altogether as interesting reading as can be found in any books of travel. (Anonymous 1882).

The spring-summer of 1882 saw McKay travel with Yup’ik guides and paddlers by baidarka from Nushagak around Etolin Point into Kvichak Bay upstream on the Kvichak River and eastward across Iliamna Lake to Old Iliamna village, where he likely secured two Dalls sheep horn spoons from the Dena’ina. The sheep horn specimens came from the Chigmit Mountains. Osgood believed McKay obtained the sheep specimens at the Dena’ina village of Old Iliamna. But Osgood felt the Iliamna Dena’ina probably obtained the sheep parts from their kinfolk on Lake Clark, because, based on his 1902 visit, Dall sheep were not known to commonly inhabit the mountains around Iliamna Lake. In addition, McKay’s accession records from 1883 list “Clothing of Kenai Indians,” that he could have collected himself at Old Iliamna during his 1882 visit or from one of the Mulchatna villages he perhaps visited during the winter of 1882 or 1883 (Osgood 1904).

McKay collected a pika in the Chigmit Mountains and noted, “Indians in their vicinity have a superstitious dread about killing them, and cannot be hired to do so.” (Jordan 1883).Osgood said “McKay was unquestionably a careful and enthusiastic collector, and his accidental death at an early age was a distinct loss to science.” (Osgood 1904). On May 19, 1883, about a month after McKay died in Nushagak Bay, Baird, not knowing of his death, wrote him saying the collections he sent back to the Smithsonian had “extreme value” and “great importance.” (Baird 1883).

Courtesy of the Elizabeth Butkovich Collection.

As late as 1882, the Iliamna-Lake Clark region had rarely seen a Euro-American traveler. Perhaps Alphonse Pinart, the French ethnographer-linguist, was the first non-Russian white man to see Iliamna Lake when, in 1871, he and Yup’ik guides paddled baidarkas up the Kvichak River to the lake’s outlet and then returned to Bristol Bay. It is very likely that McKay was the first documented American to see the lake north of Iliamna Lake, which the Dena’ina called Qizhjeh Vena, before it was named Lake Clark in February 1891 by New York City writer-explorer Albert B. Schanz (Haakanson and Steffian 2009).

The Demise of McKay and His Legacy of Scientific Inquiry

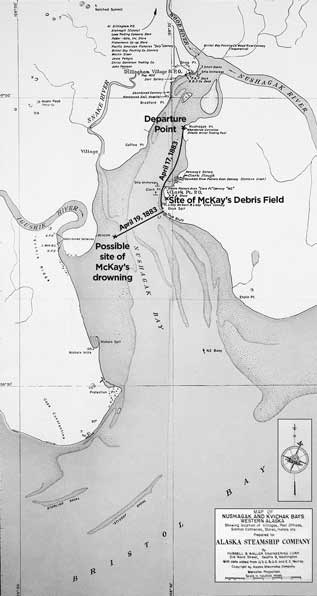

It is my sad duty to inform you that your son left this place on the 17th of April, to make a short trip for the purpose of making collections, and that he never returned. He left in company with a Native, each of them in a single canoe and passed the night in an Indian village, sixteen miles from the station. The following day was very stormy and they lay over in the village. On the morning of the third day it being calm weather, they left the village to cross over the bay, a distance of twelve miles. They were accompanied from the village by three other Native canoes. When about two thirds of the way across a strong adverse wind sprang up. In some manner, he was left behind and that was the last that was seen of him. On the 22nd the report reached me and the same day we began to search for him. We found broken pieces of his canoe, a gun, his rubber boots, hat and various little articles on the beach about a mile on this side of the village they left that morning. We continued the search for over three weeks, but could not find the body. Such is a brief account of all that is at present known of the manner in which he was lost. I can readily understand with what feelings you will receive this letter, and believe me that if the sympathy of a stranger can serve to mitigate your grief in the slightest degree, you have mine. Being my sole companion for two years, I had learned to appreciate him and to esteem his manly, upright character. Your very obedient servant, John W. Clark. (Clark 1883).

McKay seemed to foretell the cause of his own demise when he wrote Baird about the dangers of kayak travel on the waters of Bristol Bay. In a September 1881 letter to Baird, McKay wrote: “It has to be pretty quiet down on the coast or there is no getting the Indians [Yup’iks] to venture out. On the last trip I wanted to go out fishing, but the Indians would not stir as it happened to be a little rough . . . I believe that I will get a baidarka for my own use this coming season.” (Baird 1881).

University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, John Cobb Collection, 4179.

Another letter, written by Nelson Groom of the Signal Service in San Francisco to General Hazen on July 19, 1883, tells of a letter from an unnamed Alaska Commercial Company agent at Unalaska. Groom wrote: “I regret to inform you of the drowning April 19 of Charles L. McKay . . . who had left Nushagak on the breaking up of the river to go with a party to Cape Constantine on a collection tour and on his return the accident occurred; his party was ahead and a very strong gale blowing at the time, and did not see him capsize, but from the finding of his gun and a portion of the wreck of his baidarka, concluded it must have happened by his trying to make a landing on the ice. His body was not recovered.” (Groom 1883).

McKay’s mother, Sarah A. McKay, wrote to Baird on September 14, 1883, enclosing a copy of Clark’s letter. She stated that Clark’s letter “differed in some respects from the one sent by you [Baird] to us from the department. You will notice that it was three days after the accident occurred before they got word to Mr. Clark. In a letter written the first of April Charles told of making the same trip and back in the same day.”

In a post script, Mrs. McKay reflected both her maternal grief and a widespread, 19th-century Euro-American bias against Native Americans: “It seems to me that the Natives must know more of the matter than they choose to tell. Perhaps an investigation of the other side of the Bay might reveal something. No one can tell a Savages [sic] motive for what he may do. I have just read of Alaska Indians killing white men.” (McKay, S.A. 1883).

Courtesy of the Alaska State Museum, Juneau 2011-21-20.

In a post script, Mrs. McKay reflected both her maternal grief and a widespread, 19th-century Euro-American bias against Native Americans: “It seems to me that the Natives must know more of the matter than they choose to tell. Perhaps an investigation of the other side of the Bay might reveal something. No one can tell a Savages [sic] motive for what he may do. I have just read of Alaska Indians killing white men.” (McKay, S.A. 1883). Rumors persisted into the 20th century of foul play in McKay’s death. Sarah McKay’s sentiments indicated she felt her son’s death might have been the responsibility of his Yup’ik companions. The implication of Mrs. McKay’s letter was that perhaps some Nushagak people resented McKay collecting artifacts and natural history specimens, and somehow caused his death. In 1904, Osgood wrote, “rumor at Nushagak still persists to the effect that the drowning of McKay was brought about by foul means.” However, later Osgood wrote that McKay’s “accidental death at an early age was a distinct loss to science.” Yet there is no evidence to suggest that McKay’s death was anything but a tragic accident, albeit one exacerbated by extenuating circumstances (Osgood 1904).

Perhaps the genesis of rumors of foul play was propagated by the next visitor to Nushagak to leave a written record. On April 30, 1883, Danish ethnographer and collector Johan Adrian Jacobsen arrived near the scene of the accident 12 days after McKay drowned. He made no reference to criminal behavior in reference to McKay’s death, but he did excoriate the behavior of McKay’s Yup’ik traveling companions. Jacobsen and his four Togiak guides traveled in three small craft, probably two baidarkas and one kayak, paddling around Cape Constantine and crossing Nushagak Bay to Clark’s trading station:

We reached the village of [Ekuk] where I [met] young Kasernikoff (whose father was murdered by the Indians in Nulato 2 years ago)—he was busy searching for the body of the young signal service officer Mr. McKy [sic], who capsized in a snowstorm about [twelve] days ago on a hunting and collecting expedition, and drowned. There were several Eskimos with him and he was abandoned by these cowards when the storm came—they have found his gun and almost all things but not his body . . . This station [Nushagak] was unfortunately without an occupant because Mr. Mackay [sic], who had been there, was drowned during a hunting expedition . . . It was not possible for me to find anything at this place because Mr. Mackay [sic] had bought everything the Natives possessed for the Smithsonian Institution. . . . Here is a signal station . . . and the present observer [McKay] has plundered the entire area . . . and has in his collection a few nice things. The Eskimo are now annoyed that they have sold all of their stone axes and knifes etc. to him because I promised them higher. But it is too late because everything has been sold . . . the signal officer here lost his life a few days before I arrived because he went to hunt with some Natives and was shameful-ly left behind by the Eskimo in a snow storm when his kayak was cut in two by the ice and he drowned. (Jacobsen 1883).

Courtesy John Branson

Neither Clark nor the other two informants mentioned foul play as a possibility in McKay’s death. There was never any official government investigation of McKay’s death, nor did any documented contemporary account of his demise offer any credible evidence of foul play. Surely, if Clark had any suspicions of foul play in the death of his young friend, he would have informed the U.S. Signal Service. McKay’s successor, James W. Johnson, who arrived at Nushagak the summer of 1884, apparently never asked his superiors in San Francisco and Washington, D.C., to open an investigation into McKay’s death.

Patience and deference to the forces of nature were part of the Yup’ik culture, coupled with broad experience on the water. When the weather turned bad, Yup’ik men, who had life-long experience in skin boats on the Bering Sea, were far better prepared to deal with adverse weather than a young man who had only been in Alaska two years. McKay had little experience on Nushagak Bay, with its fearsome, 25-foot tides, spring ice floes, and sudden snowstorms with accompanying gale force winds. When the going turned very bad, perhaps it was every man for himself; McKay’s kayak was disabled, and he could not keep up with his Yup’ik companions.

As tragic as McKay’s death was, his legacy of work in the Bristol Bay region as the first resident scientist was considerable. Captain J.N. Mills of the U.S. Signal Service sums up the value of McKay’s contributions: “the . . . service has lost a faithful, intelligent and efficient member and that his service in connection with meteorological work of this office in Alaska has been highly appreciated . . . I am informed by Professor Baird that he had rendered extremely important service to the Smithsonian Institution and National Museum.” (Jordan 1883). In addition, McKay is considered to be the first documented Euro-American to see Lake Clark.

The tangible results of McKay’s few years of collecting at Nushagak include about 363 mammal and bird specimens and 123 plant species. He also collected mineral and important ethnographic specimens. His collection of Dena’ina and Yup’ik skin clothing is important to better understand the material culture of the Native people of Bristol Bay. In recognition of his excellent service, McKay’s Bunting, Plectrophenax hyperboreus, a rare passerine bird, was named after him (Mearns 1993).

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 14 Issue 1: Resource Management in a Changing World.

Last updated: August 13, 2015