Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Bob Reeve is arguably one of Alaska’s most recognizable bush pilots. Although his independent airline, Reeve Aleutian Airways, pioneered commercial routes from Anchorage throughout the Alaska Peninsula and the Aleutian Chain between 1947 and 2000, the pilot is most known for his ability to land and take off from glaciers located in a region that would become Wrangell-St.Elias National Park and Preserve.

But what is often overlooked in the accounts of Reeve’s early aviation activities in the Wrangells is the role that Alaska’s mining industry, bolstered by New Deal legislation, played in launching the “glacier pilot’s” historic flying career.

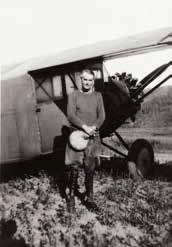

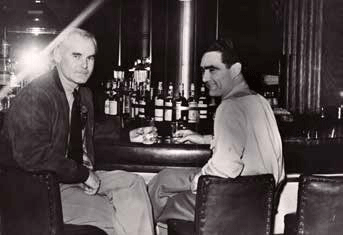

Bob Reeve File. Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum, Anchorage, Alaska.

After his first flight in 1932, Reeve became an astute student of the towering peaks surrounding Valdez. While circling summits and studying the tongues of ice that flowed forth from the barren, steep slopes, the pilot, with a prospector’s instinct, remembered thinking, “It was hard to realize that in such an inhospitable, nearly impassable land lay the riches of the earth” (Day 1961). The so-called “easy-to-gather” ore had long since disappeared from Alaska and the Yukon, and by 1932, “Valdez,” as Reeve described it, “was a dead town” (Day 1961). But prompting Reeve’s interest were claims made by geologists that rich quartz lodes still lay in the inaccessible mountains and were scarcely touched because of the expense and physical labor of reaching them. Besides the famous Chugach mines that once made Valdez a mining hub before the Great Depression, Reeve guessed that the Wrangell Mountains stretching eastward, with little or no distinguishable break on the horizon, held the type of riches that to the pilot meant more flying and a promising future.

Winter Flying in the Wrangells

It did not take long for Reeve to encounter extreme weather conditions, which provided him a strong awareness of the natural surroundings that, among other things, was crucial for success in Alaska’s aviation business. Flyers understood the region as a land of contrast and change. “The way of the pilot is hard in that country and the perils which lie over and beneath the white blanket of snow are many,” warned the New York Times in 1932. “In the Alaskan winter-time this means . . . a fight for life.” “It is no wonder,” remarked writer Harmon Helmericks, “that the old pilots were all weather-wise.”

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

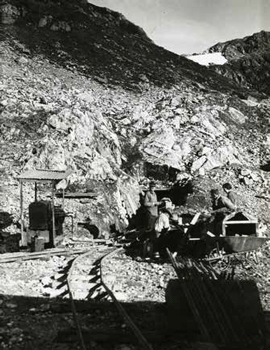

To Reeve, being “weather-wise” was simply part of the job, a skillset he most certainly perfected during his first contract work in the Wrangells. The job consisted of flying supplies into the isolated Chisana region. At the time, the only way into or out of the struggling year-round mining camp was hauling supplies over the mountains by horse and sled, or if one could afford it, charter a flight with Gillam Airways. Reeve was hired to fly supplies to Chisana at twenty cents a pound—an affordable price. In order to keep costs low, Reeve found the most efficient way to fly in goods was to truck fuel and freight up the Richardson Highway from Valdez to Chistochina, where he based his rented Eaglerock at the Chistochina roadhouse. From there he flew supplies over the Wrangells to Chisana.

By 1932, roadhouses were well equipped to serve Alaska’s flyers. Instead of dog mushing kennels, many roadhouses now provided airstrips, encouraging weary pilots to stay overnight. The Copper Center roadhouse, run by Florence “Ma” Barnes, was a preferred base for flyers because it offered a telephone line on which pilots could call in for weather reports. By mid-November in the Copper River Basin, temperatures drop as quickly as the daylight disappears. No matter the the oil from their plane upon landing. If a pilot neglected this critical procedure, the oil would freeze like water, irreparably damaging the engine.

Reeve recalled that during these first winters he had to beg the roadhouse proprietor to allow him to warm the oil overnight near the stove. Through cooperation and good manners, Reeve found that the cooks became “as plane-wise as the flyers,” for they routinely set the oilcan next to the stove before they started to grill the hot cakes (Day 1957). Before taking off, pilots had to warm the motor with a fire pot, which had to be covered with a tarpaulin to keep wind from extinguishing the flame.

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Chisana miners anticipating Reeve’s arrival often met his plane at the airfield. “A bush pilot was expected to serve as mailman, message-carrier, and purchasing agent for the men who stayed the year-round at the mine sites,” recalled Reeve. Like the roadhouse staff that accommodated pilots, to the isolated miners who appreciated items brought to them from distant markets, pilots recognized their role in a new elaborate system linking Alaskans to the modern world. Still, Reeve maintained that instead of transporting modern American life—along with its commodities, technologies, and business—into the most remote places of the north, his air services carried on a spirit of frontier Alaska. “It was much more than a packet of needles or a can of snuff. It was their assurance that they were still a part of the outside world,” explained Reeve, “and it was a tradition of Alaskan fellowship” (Day 1957).

In spite of Reeve’s contention that aiding isolated miners was the Alaska way, during the worst years of the Depression, the gesture nevertheless lacked good business sense. As Reeve himself pointed out, it was always difficult to receive actual payment from them. So instead of concentrating on cash-strapped miners, Reeve began to specialize in the transport of freight. His competition in the Wrangell Mountain area seemingly preferred to fly people, because passengers could, as Harold Gillam put it, “use their two legs” to walk off his plane. The pragmatic Reeve had a different view. His response to Gillam: “It [freight] didn’t ask questions” (Day 1957). But more importantly, the mining companies that chartered flights with Reeve generally paid their bills.

Aviation's Golden Era

It turned out that Reeve started his airfreight business at the perfect time. Even though the mining giant Kennecott Copper Corporation had temporarily closed its mines, which marked the inevitable decline of the region’s copper production, the impact of the Depression cut costs for equipment and other supplies, which exponentially reduced overhead costs for gold lode mining operations in eastern Alaska. Additionally, Congress passed legislation in 1932 relieving owners of the obligation of having to conduct annual assessment work, except those who were required to pay federal income taxes. Most significantly, however, prosperity in the gold mining industry came from new federal policies directed at replenishing the nation’s precious metal reserves.

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

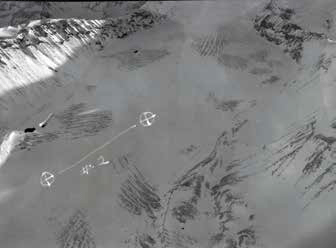

Figure 5. Bob Reeve fixed his Fairchild with homemade skis, and the mudflats that fronted Valdez was his airstrip, dubbed “Mudville” by his rivals. “While other pilots were operating by clock and calendar,” recalled Reeve, “I began using a tide book for a manual of operation.” Because work kept him mired in a muddy mess that smelled of rotting salmon and decaying seaweed, Reeve was known as a fairly filthy flyer. Not everyone was impressed with Reeve’s dirty flying, however. Reeve’s frequent advertising target, the meticulously clean Harold Gillam, remarked, “Reeve can have it!”

Across the nation, desperate people were pulling their life savings from local banks, forcing them to close. Without capital available for new investment, the economy stagnated, coming nearly to a complete halt in 1932, the year Reeve arrived in Valdez. Soon after his inauguration in 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt signed a series of executive orders designed to prevent the run on and, ultimately, failure of banks, which culminated in the Gold Reserve Act of 1934. This piece of New Deal legislation made the Federal Reserve Bank the only financial institution that could legally buy gold. In fact, the law criminalized the holding or acquiring of gold by any U.S. citizen. The law also required that all newly mined gold in the country had to be purchased by the U.S. Treasury. Most significantly, the Gold Reserve Act increased the nominal price of gold from $20.67 per ounce to $35.00. The nearly doubling in value inflated the federal government’s gold holding $2.82 billion overnight. The surge in gold prices also made it remarkably profitable to mine gold.

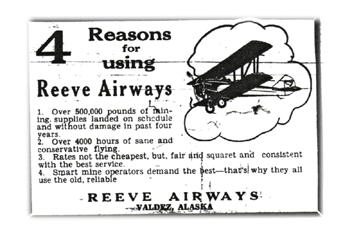

Figure 6. In early 1934, Reeve sought to capitalize on the economic upturn, placing an announcement in the Valdez Miner that read: “Prospectors, Attention! Gold is where you find it; but you can’t beat the Chisana, Nabesna, Slate Creek, Chistochina and Bremner gold bearing districts as some of the best bets in Interior Alaska in which to make that pile.” When a miner had his outfit ready to go, the ad insisted, “Always use REEVE AIRWAYS!” A similar advertisement was printed in the Valdez Miner in 1937.

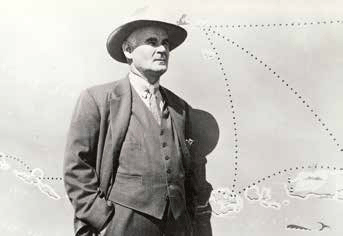

In Alaska, where stories of gold rushes and independent sourdoughs continued to resonate with citizens, the Gold Reserve Act gave a tremendous boost to the depressed mining industry. As Governor John Troy reported, “Never before have the material prospects for this Territory been brighter than now” (Cole 1989). Writer Rex Beach referred to such federal support as “a bit of intelligent government aid” (Beach 1936). Thanks almost entirely to an artificial, federally-controlled market, mines that had not been working for years suddenly reopened. The independent-minded citizens of the Last Frontier were too busy to be concerned that gold mining had become a noncompetitive industry.

Valdez, like other dormant gold rush towns, returned to life, as miners streamed into town with “cleanups” of gold bricks. Territorial journalists proclaimed the Prince William Sound port as “the Key to the Golden Heart of Alaska” (Valdez Miner 1934). Most significantly for flyers, mining investors could now afford to charter flights to remote prospects and develop new lode claims. While the country’s economy would remain stalled for several more years, Alaska’s revitalized mining industry took off with the help of the federal government and a new mining tool—the airplane.

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Without the federal law significantly increasing the price of gold it is likely that Reeve Airways never would have left the ground. But the reopening of the high altitude lode mines, combined with increasing investment in exploration, kept Reeve in the air almost around the clock. For the summer months, Reeve made a deal with the mine owners that when they needed fresh supplies, they would send a man on foot down to the town with the order. Bob would then fly the order out to the mine and deliver it by airdrop.

Clarence William Poy, mining engineer and manager of the Bremner lode mine, told the Valdez Miner that “parachuting a 1,000-pound diesel engine from an airplane above an Alaskan mine is one of the latest achievements of aviation in assisting the prospector in the pioneer country, to say nothing of dropping dynamite, carbide, canned goods, lumber, drill steel, meat, oil and, in short, everything but eggs into the heart of the frozen North” (1934). Besides the booming mines in the vicinity of Valdez, Reeve Airways—thanks in part to strategic advertising—also picked up increased business from developing mines in the Wrangell Mountains, such as Chisana, Nabesna, and the new gold mine at Bremner, in the isolated Chugach range.

Mudflat Takeoffs and Glacier Landings

The rising demand for business after 1934 also allowed the pilot the opportunity to develop such a distinctive operation that it would quickly manifest into a brilliant reputation and moniker for which he would forever be known. Following trends set by European aviators landing in the Alps, Reeve began flying supplies into mines throughout the Chugach and Wrangell Mountains, landing on makeshift strips near the diggings.

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Figure 8. A so-called “scout of the sky,” Reeve rebuilt and used Owen Meal’s wrecked Eaglerock, and later his Fairchild aircrafts, to prospect for undeveloped mineral deposits throughout the Chugach and Wrangell Mountains. Besides transporting miners and supplies, his ties with the mining industry ran deep. Reeve owned 846 shares of Yellow Band stock at Bremner and even named his youngest son Whitham, for his friend Carl Whitham, owner of Nabesna mine. He was also part owner of the aptly named Ruff & Tough Mine.

Existing in close proximity to most high mountain lode mines were alpine glaciers, where even in summer, winter ruled. Reeve found that, for the most part, the snow on glaciers froze as hard as concrete. He replaced the Fairchild’s wheels with wooden skis, instantly making each glacial field a possible landing strip that provided access to the protruding quartz lode deposits.

After a series of trial and error attempts landing on the constantly changing and potentially deadly rivers of ice, Reeve perfected his new niche by paying close attention to the relatively unknown glacial environment. He learned to land in flat light on a featureless glacier by making a preliminary pass while throwing out dark objects, such as gunnysacks dyed black, or willow boughs, anything that gave him depth perception. He also set up flags and sprinkled lampblack to mark the landing area. Reeve learned to identify the location of the mostly hidden crevasses by looking for a slight undulation on the surface, where snow was not quite as blue as the surrounding field. Reeve’s rule of thumb: the lighter and drier the snow, the more dangerous on which it was to land. Finally, akin to a hockey-stop, he learned to turn his plane to a 90-degree angle on the slope before cutting the engine so as not to slide backward.

From the Jack Peck File, courtesy Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum.

Figure 9. Although Bob Reeve and Harold Gillam respected each other as pilots, their views on government regulation of Alaska aviation diverged. Gillam believed regulation would make flying safer and more economical, while Reeve believed it would bring more government interference to flying. Pictured are Reeve and Gillam in Anchorage for the Civil Aeronautics Board Hearings in 1939. The main problem facing Reeve’s innovative glacier flying was that by May, snow on the Valdez airstrip had melted, making it impossible to reach the alpine mines with skis during the warm months of late summer. By winter, when he could finally replace his wheels with skis, the lodes had disappeared with the quickly accumulating snowfall. Reeve, something of a mechanical virtuoso, solved this problem by fixing his Fairchild with stainless steel homemade skis and taking off from the mudflats that fronted Valdez at low tide. But unlike snow, the sticky mud created suction on his skis, making it extremely difficult to get airborne. Once in motion, Reeve had to physically rock the plane in order to tear the skis loose (Beach 1936). The hassle proved prosperous, however, for this inventive mudflat takeoff technique allowed him to serve mines year-round. “While other pilots were operating by clock and calendar,” recalled Reeve, “I began using a tide book for a manual of operation” (Day 1957).

Courtesy of Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum.

Figure 11. When Reeve died on August 25, 1980, an estimated 600 mourners attended his funeral service at the Sydney Laurence Auditorium in Anchorage. Pictured is Bob Reeve at the Reeve Aleutian Airways office in Anchorage, Alaska.

Tourists arriving via steamship often gawked curiously at Reeve’s “airport,” dubbed “Mudville” by his rivals. Within a year and a half of his arrival, Reeve had developed a reputation as being “intensely competitive” and “fiercely proud of his skill in the air” (Beach 1936, Day 1957, and Roberts 2002). Reeve’s glacier and mudflat flying skills, besides boosting the mining industry, sparked the imagination of a depressed populace whose collective lives had little opportunity or reason for excitement. Rex Beach wrote several articles promoting Alaska mining that centered

on Reeve. The renowned author wrote passionately on his contention that the federal government should invest even more money to create a modern infrastructure for aviation in Alaska.

For its efforts, argued Beach, the Territory would attract a fleet of “sky prospectors,” who in his mind were “the quickest way to unlock Alaska’s golden treasure chest and provide thousands of immediate jobs for young, out of work Americans.” (Beach 1936).

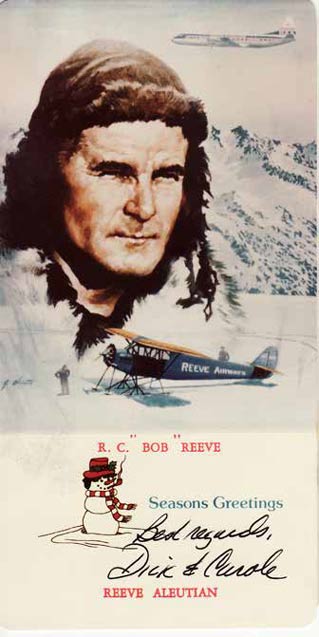

Reeve Aleutian Christmas Card, courtesy Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum.

Figure 12. Although Reeve’s modern airline, Reeve Aleutian Airways, flew passengers throughout the Aleutian Islands until 2000, his “glacier pilot” persona, developed while flying for a brief time in eastern Alaska, remained central to his public identity.

The End of an Era

By the end of the 1930s, the glacier pilot’s “anything goes” approach to flying for the mining industry came to an end as a result of government regulation and the start of World War II. In 1938, the federal government took its first steps to regulate the nation’s aviation industry, calling for the establishment of a safe and reliable air transportation system and, for the first time, a distribution of mail contracts. Most significantly, however, the Civil Aeronautics Act established Alaska’s first scheduled commercial air routes.

The year 1938 was especially bad for Reeve. After several nationally recognized glacier flying achievements in 1937, a combination of landing accidents, a windstorm, and a hangar fire left him without a plane for six months. This allowed his rivals to monopolize service to Chisana, Nabesna, McCarthy, and Bremner.

More significantly, the Civil Aeronautics Board determined outcomes and ultimately granted certificates to a flyer based on the “Grandfather Clause.” The clause stated that any pilot or air service that provided regular flights over a given area between May 14 and August 22, 1938, would retain exclusive rights to serve that area from that time on. At the time, Reeve had no planes to conduct business, and therefore, the competitive pilot was ironically squeezed out of Valdez and most of eastern Alaska by an unlucky fluke in the federal law.

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Figure 13. Bob Reeve wearing his trademark rain hat is shown working on his plane, preparing to take off from the Valdez mudflats around 1937. 1937 marked his last year serving mining camps in the Chugach and Wrangell mountains.

But the real hit to aviators like Reeve, whose business depended almost entirely upon the mining industry, was the federal government’s reasoning that it made no sense to spend precious resources on further domestic production of the precious metal. Thus, the deathblow for the gold mining industry came on October 8, 1942, when the War Production Board declared gold mining a nonessential industry and ordered most placer and lode gold mining on American soil to cease indefinitely. Faced with uncertainty, the Nabesna and Bremner mines closed, and Reeve moved his family to Fairbanks, confiding later to his biographer, Beth Day, “I was forty years old, with a growing family, one beat-up plane and no future” (Day 1957). For Reeve, the decision to leave the Wrangell Mountains was personal, for the pilot was intimately connected to the surrounding mining operations. He owned 846 shares of Yellow Band stock at Bremner and even named his youngest son Whitham, for his friend Carl Whitham, owner of Nabesna mine.

Indeed, the ban on gold mining coupled with Reeve’s departure from the Wrangells marked an end of an era in eastern Alaska. But Reeve, like the rest of the country in 1941, went to work instead of giving up. He left behind his glacier pilot persona to help the United States military transform the Territory into an air bridge, which greatly aided the victorious Allied campaign in Europe and left behind an expanding web of aviation infrastructure that would underpin modern Alaska. After establishing the Northway airfield via Nabesna River, Reeve continued to fly for the U.S. military, helping to establish a chain of air bases in the Aleutians during World War II. When peace came, Reeve had accumulated the experience, as well as enough military surplus aircraft, to conduct a viable air service along the stormy, volcanic island chain. In 1946, he established Reeve Aleutian Airways, which, through his constant guidance, became one of Alaska’s most successful and modern airlines, flying passengers over some of Alaska’s most hostile terrain until competition and high fuel prices shut down company operations in December 2000. When Reeve died on August 25, 1980, just months before the passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) converted his old flying territory into Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, the editor of the Anchorage Daily News reminded readers that men like Bob Reeve carried to Chisana, Nabesna, and Bremner what writers for decades had described as the spirit of frontier Alaska.

References

Beach, R. 1936.

The Place is Alaska—the Business is Mining. Cosmopolitan (January).

Beach, R. 1936.

Alaska’s Flying Frontiersmen. American Magazine (April): 42-43, 96-101.

Beach, R. 1939.

Valley of Thunder. New York: Grosset & Dunlap.

Cohen, S. 1988.

Flying Beats Work: The Story of Reeve Aleutian Airways. Missoula: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company.

Cole, T. 1989.

Golden Years: The Decline of Gold Mining in Alaska. Pacific Northwest Quarterly Vol. 80, no. 2, (April): 62-71.

Day, B. 1957.

Glacier Pilot: The Story of Bob Reeve and the Flyers Who Pushed Back Alaska’s Air Frontiers. New York: Henry Holt and Co.

Day, B. 1961.

He Looked Like a Tramp. Early Air Pioneers: 1862-1935. New Work: Franklin Watts, Inc.

Hartsfield, K. 1973.

Reeve’s Unique Family Airline. Alaska Industry (January): 34-35.

Haycox, S. 2002.

Frigid Embrace: Politics, Economics and Environment in Alaska. Corvallis: Organ State University Press.

Helmericks, H. 1969.

The Last of the Bush Pilots. New York: Alfred A. Knoff, Inc.

Koontz, G.B. 2007.

Alaska’s 1930s Bush Pilots: Remarkable Fliers and Creative Mechanics Keeping the Engine Oil Warm at 60 below. Aircraft Maintenance Technology (April): 36-41.

Patty, E.N. 1937.

The Airplane’s Aid to Alaskan Mining. Mining and Metallurgy (February): 92-94.

Potter, J. 1945.

The Flying North. New York: Macmillan Company.

Roberts, D. 2002.

Escape from Lucania: An Epic Story of Survival. New York: Simon & Schuster.

War Production Board Limitation Order L-208, 7 Fed. Reg. 7992-7993.

White, P.J. 2000.

Cultural landscape report: Bremner Historic District, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska. Anchorage Regional Office, National Park Service.

New York Times. 1932.

Resourceful Air Pilots of Alaska. March 6.

Valdez Miner. 1934.

Reeve Airways Advertisement. February 24.

Valdez Miner. 1934.

Mining Activity Keeps Pilot Bob Reeve Busy. March 31.

Valdez Miner. 1934.

Pilot Reeve Sets Record in Freighting this Winter. May 5.

Valdez Miner. 1934.

Valdez Pilot Makes Many Trips, Interior. June 2.

Valdez Miner. 1934.

Pilot Reeve and Mechanic Egan Back From Trip. December 14.

Valdez Miner. 1934.

Valdez Alaska: The Key to the Golden Heart of Alaska. December 14.

Valdez Miner. 1935.

Development is Speeded Up By Airplane: Pilot R.C. Reeve Tells of Advantages over Former Methods of Transporta-tion. February 22. (previously published in the Denver Mining Record).

Valdez Miner. 1935.

Parachute Drops Heavy Machinery Supplies Safely: Air Transport Plus Parachute Delivery Gets Supplies, Fuel, Food to Camp in Eight Days. March 15.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 13 Issue 2: Mineral and Energy Development.

Last updated: August 24, 2020