Howard Zahniser’s Vision of Wilderness — and the Whole Community of Life on Earth

My father, Howard Zahniser, (Figure 1) was the primary author of the Wilderness Act of 1964. To understand his vision of wilderness, it is good to start with his literary mentors. He was bookish: In 1945, some members of The Wilderness Society governing council thought he was not enough of “a wilderness man” to be hired that year as the Society’s Washington, D.C., presence and the editor of its quarterly magazine The Living Wilderness. Indeed, recent writers have pictured him “more like a librarian” than an outdoorsman.

Zahnie, as he was known to friends and associates, was born in western Pennsylvania in 1906, the year President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act and proclaimed Devils Tower the first national monument. Zahnie grew up frugally, and later surrounded himself—and his family—with a riches of books. My mother Alice Hayden Zahniser, now aged 96, put her foot down when her husband wanted to shelve books in the kitchen, too, atop the refrigerator.

The furnace room and attic already held bookcases. Because our house, built in 1929, was not insulated, Zahnie had fashioned floor-to-ceiling bookcases to insulate the hallways on both floors. Shelving options grew scarce. As the youngest of four children, I was the last living at home. As he and my mother and I ate dinner, he would broach some topic.

Then, when my mother might slip into the kitchen, he would ask me to go out to the trunk of the car where I would find a book on that topic. “Bring it in please,” he’d say, “and while you’re at it, why not bring in two or three more from the carton of the books?” Owners of two of Zahnie’s favorite used-book shops routinely gave me a free book shortly after we arrived—to occupy me so my father could shop longer.

Zahnie mainly collected books on art, literature, and natural history and conservation. His art and literature collections especially favored books on the Hebrew Scriptures’ Book of Job and by or about Italian poet Dante Alighieri, English poet and engraver William Blake, and American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau.

In the Book of Job, after Job is wiped out of everything, including his family, God takes Job on a world tour. Old Testament scholar William P. Brown writes in “Where Job and the Wild Things Are”: “The world according to God is not finely tuned to ensure humanity’s flourishing, let alone dominion. No, the world is a hodgepodge of life in all its wondrous and repulsive variety. It is a world of ‘ultimate pluralism,’ with Job included in the mix. Singling out one particular animal, God says to Job: ‘Behold Behemoth, which I made with you. (40:15a)’”

“The clue is in the preposition,” Brown continues. “Behemoth is created with Job. . . . Job shares an identity, indeed a genetic identity, with this fearsome creature. Job’s DNA . . . is linked to this lumbering, fearless, playful creature of the wild. Job is no isolated creation, and clearly not the apex of the created order.”

Aldo Leopold, an original Wilderness Society council member until his death in 1948, wrote that wilderness is “an antidote to the biotic arrogance” of Homo sapiens. Preserving wilderness shows restraint and humility. Preserving wilderness makes some room for permanence as well as for change. It treats some remnant of the land as community, not commodity. These were tenets of Zahnie’s vision of wilderness. To preserve wilderness and wildness was, in effect, to redefine American notions of progress. The Wilderness Act can be seen as a significant sociopolitical step that our culture has taken toward Aldo Leopold’s vision of a land ethic. The Wilderness Act can be seen as a step toward drawing the biosphere into our circle of ethical regard, as a step toward recognizing ourselves as interdependent members of the whole community of life.

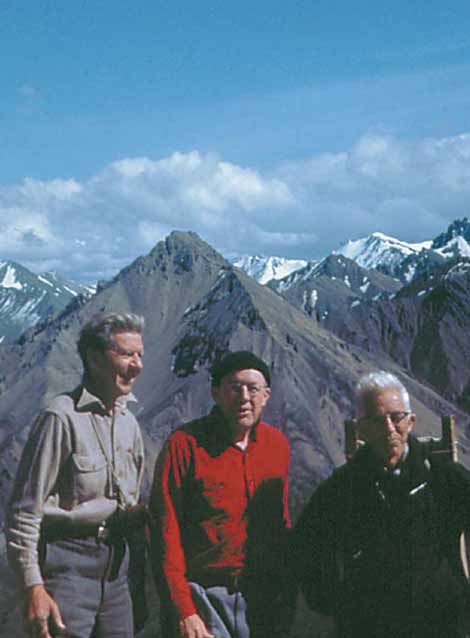

In his magisterial Comedy, Italian Poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) has a vision of Paradise but discovers that you must first go through the Inferno and Purgatory to get there. The lesson? Maybe it’s that realizing a vision demands that you be consistent, persistent, and actively patient—and hold to your vision, confident that it indeed involves a paradise. My favorite quotation about my father came from his longtime close associate Olaus J. Murie: “Zahnie has unusual tenacity in lost causes.” (Figure 2)

Figure 3. Plate 17, William Blake’s The Book of Urizen (1815), showing Urizen, who represents humanity’s overweening rationality, entangled in a fish net, for which an old term was trammel, a form of the word untrammeled that Howard Zahniser used in the definition of wilderness in the 1964 Wilderness Act. Designated wilderness is land onto which we choose not to project human desire.

English poet and engraver William Blake lived from 1757 to 1827. Blake’s axis of evil was the rationalist-materialists John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton. Blake saw the fullness of humans being taken captive by an overbearing or overweening rationality. In The Book of Urizen, Blake illustrated Urizen—who represents rationality—immobilized in a mesh or net of his own making (Figure 3), and Blake called that netting a “trammel.” This may well be where my father saw both the richness and the lack of physical specificity of the word untrammeled as ideal for defining wilderness. As a writer, my father also learned from Blake the engraver that, as Blake’s biographer Peter Ackroyd writes, “words were precious objects carved out of metal.”

Eight years before the 1964 Wilderness Act was signed, the first wilderness bill was introduced by U.S. politicians. But it took many more years to achieve the final product (Figure 4). In fact, The Wilderness Society council had voted in 1947 to pursue some such protection. That makes it an eighteen-year effort. But our wilderness movement can be traced back to 1894, when Bob Marshall’s father Louis Marshall and others inserted the “forever wild” clause into the New York State Constitution. Or wait: Our wild lineage goes back even further, to 1864 when George Perkins Marsh published his book Man and Nature. Marsh’s book—it has never been out of print—demonstrated that late great civilizations around the Mediterranean Basin had fallen when their forests were destroyed.

Or how about the transcendentalists in the 1830s into the 1860s? Maybe it took some 180 years to achieve 109 million acres of congressionally designated wilderness. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Sarah Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau also anchor the deep lineage of our American wilderness imagination. It is especially intriguing to contemplate how closely transcendentalist Margaret Fuller’s 1830s and ‘40s campaign of social reform prefigures the 1950s progressive legislative agenda of Hubert H. Humphrey, the wilderness bills’ chief sponsor in the U.S. Senate. The 1960s Great Society program—which included the 1964 Wilderness Act—is credited to President Lyndon B. Johnson and was brought to fruition as law in Humphrey’s 1950s legislative package.

Zahnie learned a great deal about both writing and wildness from Thoreau (1817-1862). Thoreau, who would die of tuberculosis, wrote that words are precious objects formed from the breath of life itself. Thoreau also penned the intriguing mantra that “in Wildness is the preservation of the World.” The word World here is, as Thoreau makes explicit in his essay “Walking,” the Greek word kosmos. Kosmos means not only “world” but also “order, pattern, and beauty.” Notice, too: Thoreau does not maintain that we preserve wildness, but that wildness preserves us, the world, beauty, pattern, and order.

Wilderness and wildness—Zahnie wrote in 1957 “the essential quality of the wilderness is its wildness”—are integral to who we are. This is perhaps the essential mystery of wilderness and wildness. It is also why the founders of The Wilderness Society insisted that the wildness of the wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity. (Figure 5)

As wilderness activist and author Douglas W. Scott has shown, the language that opens the Wilderness Act was little changed throughout the many, many revisions made between the first wilderness bill, introduced in the House and the Senate in summer 1956, and the act’s signing in September 1964. That language expresses a vision despite its role in defining wilderness and describing the situation of wilderness. Zahnie’s vision is most clearly expressed in two of his speeches from the wilderness-bill years, “Wilderness Forever” and “The Need for Wilderness Areas.” Both speeches are found on http://www.wilderness. net in the “Wilderness Fundamentals Toolbox.”

Scott also points out that the full title that opens the Wilderness Act, which is seldom quoted, is hugely important: “An Act To establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the permanent good of the whole people . . .” For the permanent good of the whole people. “The Need for Wilderness Areas” was first delivered as a speech to the American Planning and Civic Association in May 1955. In it, after quoting at length from Robert Marshall describing the values of wilderness, Zahnie said:

- Who that can see clearly these superlative values of the wilderness . . . can fail to sense a need for preserving wilderness areas?

- Who in a democratic government that seeks to serve the public interest even for the sake of minorities would wish to lose an opportunity to realize a policy for wilderness preservation?

- Who that looks on into the future with a concern for such values would not wish to insure [sic] for posterity the freedom to choose the privilege of knowing the unspoiled wilderness?

- But are these superlative values essential?Is the exquisite also a requisite? I think it is.

- I believe that at least in the present phase of our civilization we have a profound, fundamental need for areas of wilderness—a need that is not only recreational and spiritual but also educational and scientific, and withal essential to a true understanding of ourselves, our culture, our own natures, and our place in all nature.

After introducing the first wilderness bill in the Senate in 1956, then-Rep. Humphrey inserted “The Need for Wilderness Areas” in the Congressional Record, telling his colleagues that it was the best explanation of what the wilderness bill was all about.

I think my father simply fell in love with the mystery of how wilderness is an integral necessity for human beings as part of what he called “the whole community of life on earth that draws its sustenance from the Sun.” Zahnie had grown up in an evangelical tradition that assumes that we must work to leave the world a better place. He believed that the world is a better place, and that we are a better people—despite our all-too-obvious world-altering powers—for boldly embracing the humility to take some of the wilderness and wildness that have come down to us out of the eternity of the past and to project them into the eternity of the future.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 13 Issue 1: Wilderness in Alaska.

Last updated: February 4, 2015