For nearly a century, the Organic Act has been the thread that weaves a common purpose through all the national parks.

...to conserve the scenery and the natural and

historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide

for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and

by such means as will leave them unimpaired

for the enjoyment of future generations.

Introduction

John Blong

For nearly a century, the Organic Act has been the thread that weaves a common purpose through all the national parks.

...to conserve the scenery and the natural and

historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide

for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and

by such means as will leave them unimpaired

for the enjoyment of future generations.

These words are clear and concise, but in the 1960s, with rising environmental consciousness and controversy, there were calls for more direction for NPS wildlife management. In 1962, Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall assembled a committee under A. Starker Leopold, the eldest son of conservationist Aldo Leopold, to assess wildlife management in the national parks. The Board’s seminal recommendations have since influenced the ways in which parks are managed for almost 50 years.

As a primary goal, we would recommend that the biotic associations within each park be maintained, or where necessary recreated, as nearly as possible in the condition that prevailed when the area was first visited by the white man. A national park should represent a vignette of primitive America.

Leopold’s panel knew that implementing their suggestions would not be simple. Many areas had already experienced logging, water controls, burning or unnatural fire suppression, hunting and predator control, and unconstrained grazing by livestock and wildlife. Road construction, trampling by humans and pack stock, invasive vertebrates, insects, plants, and diseases had brought other changes.

Yet, if the goal cannot be fully achieved it can be approached. A reasonable illusion of primitive America could be recreated, using the utmost in skill, judgment, and ecologic sensitivity. This in our opinion should be the objective of every national park and monument.

John Blong

At the time, many scientists and resource managers were working under the premise that natural ecosystems were fairly stable, or at least followed a predictable ecological succession, and that lands and waters could be maintained in their original condition simply by controlling how they were used. The recent realization that human activity is changing climates across the globe challenges basic concepts of resource management. If prevailing weather patterns, habitats, species distribution, and abundance have developed over hundreds or thousands of years, or more, how would park resources be affected by substantial environmental change that occurs in the span of a few decades or less?

Research reported in this issue of Alaska Park Science reminds us that land and seascape change has occurred before. Some places were very different as recently as a few centuries ago, but what would be at risk if change occurs more rapidly in the future? How far should park managers go to preserve historic “baseline” conditions when climate, land cover, fish, and wildlife populations are changing, and what should they do if the changes appear inevitable? When and where is a “hands off” approach appropriate for managing parks, and when should we give nature some help, either to resist or adapt to change? Many of today’s resource managers have experienced the unintended consequences of past decisions: species eradications and introductions, fire suppression, flood control, etc. How will today’s resource management decisions appear to tomorrow’s managers? It is hard to say, since hindsight is usually clearer than foresight, but the question warrants serious consideration.

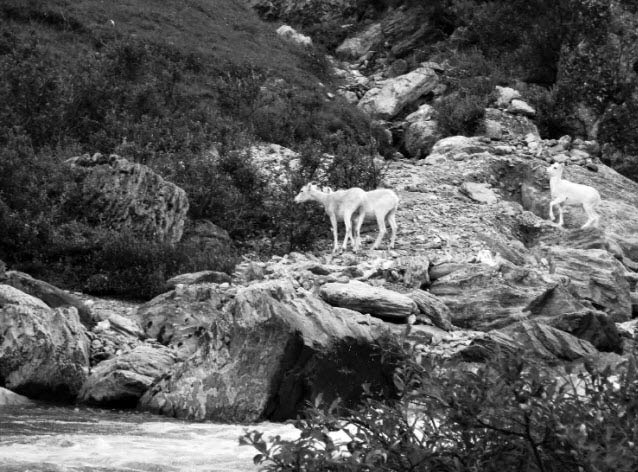

Fig 2.

NPS Photo

In August 2012, the National Park System Advisory Board delivered a report entitled Revisiting Leopold: Resource Stewardship in the National Parks to NPS Director Jonathan Jarvis. Broader in scope than Leopold’s original charge, the new report focuses on goals, policies, and actions for natural and cultural resource management. Among the committee’s more sobering conclusions is that the challenges for park management will “only accelerate and intensify in the future”, and that parks need to prepare for dealing with uncertainty. The authors suggest that the predominant goal for NPS resource management should be to respond appropriately to such change.

The overarching goal of NPS resource management should be to steward NPS resources for continuous change that is not yet fully understood, in order to preserve ecological integrity and cultural and historical authenticity, provide visitors with transformative experiences, and form the core of a national conservation land- and seascape.

Revisiting Leopold calls for extending NPS management strategies to larger landscapes beyond park borders, protecting habitat for climate refugia, critical migration and dispersal corridors, and strengthening park resilience, with consideration to time scales many generations into the future. The committee calls for prudence and restraint in park management, more fully embracing the precautionary principle, maintaining or increasing current restrictions on impairment, and avoiding actions that could irreversibly impact park resources and systems in the future, with decisions informed by broader scientific inquiry, both internal and external to the NPS.

NPS Director Jarvis has committed to a thorough review and discussions on the report’s recommendations with NPS employees, members of the scientific and parks communities, and managers of other protected areas, before NPS decides how to move forward with the report. The Alaska Region has engaged in those discussions.

The complete 2012 Leopold Revisited report at: https://www.nps.gov/calltoaction/PDF/LeopoldReport_2012.pdf

The original 1963 Leopold Report is available at: https://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/leopold/leopold.htm

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 12 Issue 1: Science, History, and Alaska's Changing Landscapes.

Tags

Last updated: August 7, 2015