Located on the Pacific face of Baranof Island in southeastern Alaska, Sitka National Historical Park is Alaska’s oldest national park unit. Every year, around 300,000 people visit the park and learn about the region’s natural attractions as well as Tlingit culture and art. Few understand, however, that people have lived in the area for thousands of years.

NPS Photo / William Hunt

Environment

Baranof Island is a mist-shrouded land of impenetrable mountains and deep fjords sculpted by eons of uplift, subsidence, and erosion. Although the island is ancient, the park lands are relatively young, the oldest portion only emerging from the ocean about 5,500 years ago. Over time, the lands of Sitka continued to rise until about AD 1250 when the park’s characteristic boot-shaped peninsula was fully in place (Chaney et al. 1995).

The island’s rugged landscape and mild, wet environment combine to generate a wealth of ecological niches. Park habitats include temperate rainforest, open meadow, estuary, anadromous river, and marine intertidal shore. The bulk of the park is a temperate rainforest of Sitka spruce/western hemlock and dense understory of devil’s club, skunk cabbage, salmonberry, and other shrubs (Krieckhaus et al. 1993, McNab and Avers 1994). The only large mammals are brown bears and Sitka deer. Birds, particularly seabirds, are abundant and aquatic life occurs in profusion where the Indian River, tidal flats, and deep oceanic waters meet (Sitka National Historical Park 2008, Sitka Tribe of Alaska Kayaani Commission 2006, Thornton and Hope 1998).

History

The earliest known human occupation on Baranof Island occurs on the northeastern shore at the Hidden Falls site. In the 1980s, archeological investigations demonstrated people were here by at least 8,000-8,600 years ago (Davis 1989). Tlingit oral history places people in Sitka Sound during an eruption of Mt. Edgecumbe, a stratovolcano on the sound’s west shore. Edgecumbe’s last eruption occurred 2500-2900 BC, placing the Tlingit here for at least 4,500 years ago (Thornton and Hope 1998). Oral histories of the Tlingit Kiks.ádi clan, traditional owners of resources in the park, place themselves at Sitka from that time through the present.

The course of this long occupation was altered in 1798 with the arrival of Russians who, in search of fur riches, lusted for Tlingit lands. In 1804, a force of Russian traders, their Aleut allies, and the Russian navy attacked. Anticipating Russian naval bombardment, the Tlingit had taken refuge in Shis’ki-Noow, a unique fortification constructed on flatlands west of the Indian River. The short confrontation ended when the Tlingit, out of gunpowder, were forced to withdraw to Chatham Strait. The Russians then built Novo Arkhangelsk (later called Sitka) on the site of the Tlingit winter village as their colonial capital and headquarters of the Russian American Company. Within a short time, the Tlingit returned and continued to use park lands in many of the traditional ways (Lisiansky 1814; 2008).

Sitka Archeological Project

Given the park’s environmental diversity, its complex physical and cultural histories, and difficulties of working in dense rain forest, several investigative techniques were used to identify the archeological resources. These included metal detection, geophysical surveys, as well as typical archeological methods of shovel testing and small-scale test excavations.

NPS Photo / William Hunt

Metal detection is generally not useful for identify-ing prehistoric sites but is an excellent method for locating historic sites. Through metal detection, the 1804 battleground site was identified. Lead musket balls indicated use of .69-caliber smoothbore muskets in the battle along with .36, .44, and .45-caliber small arms. Cannonballs, canister, and grapeshot provided formidable evidence for Russian use of 3-pounder, 4-pounder, and 12-pounder guns.

Tlingit oral histories place the 1804 fort at two locations on the peninsula: an area near its center and the other in the Fort Clearing in the south end. The goal of the geophysical inventory was to identify which was the most likely location. Investigative tools included magnetic gradient survey, resistance survey, and ground penetrating radar. Analysis of geophysical data suggested the Fort Clearing as the more plausible location. Unfortunately, massive modern disturbances prevented unambiguous identification of the fort.

Shovel testing was the workhorse for the inventory as it can identify both historic and prehistoric sites (Figure 5). Eighty of the over 1,200 shovel tests proved positive, demonstrating a very low artifact recovery rate. Prehistoric artifacts were recovered from 23 tests with all but three on the west side of Indian River. These tools (quickly made, minimal shaping, used briefly, and thrown away), made from flakes, cobbles, and split pebbles, appear to have been used for chopping, scraping, and perhaps digging. Prehistoric tools largely occurred on landforms younger than 2,000 years old with the overwhelming majority (84%) associated with landforms less than 900 years of age. Only three tools are from landforms older than 2,000 years.

Though no patterned tools were recovered, they have occasionally been found in the park. Northwest Coast ground stone “nipple top” mauls were recovered during 1940s bridge construction and during 1958 archeological excavations at the Fort Clearing. These tools were typically used to pound wedges into a cedar log to split off planking for construction of houses and as utilitarian hammers used to drive stakes or crush food (Stewart 1973). Two cobble choppers were discovered by geologists studying the developmental history of the park in 1995. In 1999, a 3/4-grooved granite maul was recovered in the Fort Clearing during an archeological excavation preceding installation of a Kiks.ádi totem pole commemorating the 1804 war leader K’alyáan. The most recent discovery, in 2009, occurred when a blown down tree exposed an enigmatic lozenge-shaped siltstone hammer-abrader. The ages of these tools remain unknown.

Charcoal is an important cultural resource indicator because rainforest wildfires are rare. Charcoal was observed in 76 shovel tests, with 20 of these having charcoal of such concentration to suggest the presence of a midden or feature. Radiocarbon dates from 23 samples ranged from 80 ± 50 to 2580 ± 50 years ago. Assuming the charcoal is from cultural activities, the dates indicate people lived in the park from the Middle Northwest Coast Developmental Stage (3,500 to 1,500 years ago) to the historic era. Twenty samples date to the Late Northwest Coast Developmental Stage (1,500 years ago to historic contact) to the early historic era (Davis 1990, Matson and Coupland 1995). Three areas in the park exhibit multiple prehistoric occupations. Patchwork distributions of charcoal in two of these locations suggested the possibility of associated structures.

After shovel testing, small scale test excavations were undertaken to clarify the cultural and temporal associations of various deposits. Eleven locations (four historic, one multi-component prehistoric and historic, and six prehistoric) were tested.

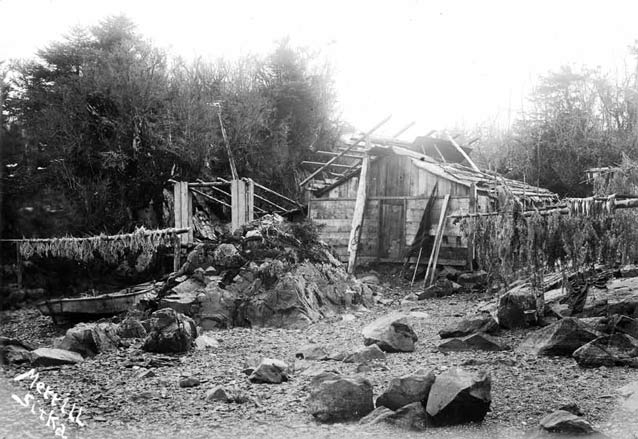

Elbridge W. Merrill. Courtesy Alaska State Library - William A. Kelly collection, ASL-P427-43.

Among the more interesting discoveries was a rectangular hearth. Its superimposition by layers of charcoal and decomposed wood along with artifacts indicate this is an element of a prehistoric structure. Radiocarbon dates indicate a circa AD 1153-1228 occupation. Additional shovel testing suggested the building may be less than 26 ft (8 m) long and wide, about the size of early historic Tlingit summer houses. Such structures often functioned both as fish smokehouse and single family dwelling (Emmons 1991).

Another exciting find was an anvil stone recovered from a pit feature in the Fort Clearing. Charcoal from the pit dated to circa AD 606-996. Initially, the anvil was believed to be a striking platform used in stone tool production; however, Kiks.ádi elders and Tlingit artists suggested cedar bark may have been pounded on it to produce fibers for weaving, or berries or meat were crushed on it for food preparation. As a result, the artifact was sent to the Laboratory of Archaeological Sciences at California State University-Bakersfield for protein analysis. Using immunological methods similar to an allergy test, both animal (bear and deer) and plant residues (Amaranthaceae and kelp) were identified. Brown bear and Sitka deer are the only bear and deer species inhabiting Baranof Island, and the Tlingit commonly ate a variety of seaweeds gathered from late winter through summer. The positive amaranth test may point to use of Alaska or Gmelin’s orach, saltbush plants in the pigweed subfamily of Amaranthaceae commonly found along the coast of Baranof Island. Although no sources consulted identify either orach variety as Tlingit foods, they have been used for food throughout the world (Davidson 1999, Newton and Moss 1984, Thornton and Hope 1998, Sitka Tribe of Alaska Kayaani Commission 2006). Based on positive tests for three known Tlingit foods and another possible plant food, it was concluded that the anvil stone was used as a tool in food preparation, possibly in production of a Northwest Coast “pemmican.” Four intriguing ovate pits about 9.8-13 ft (3-4 m) long and wide and about 5 ft (1.5 m) deep were also recorded. One pair lies within the 1804 battlefield, a position suggesting possible association with Shis’ki-Noow. Both Tlingit and Russians describe one or more pits within the fort that provided the Tlingit with refuge from Russian cannon fire. If these depressions are associated with the fort, the position of the fort shifts northwestward from that proposed by Frederick Hadleigh-West after his 1958 excavations (Hadleigh-West 1959). These and the other two depressions, however, may represent remnants of traditional Tlingit cache pits. Such pits were up to 13 ft (4 m) on a side and commonly dug behind houses to store food. Although Tlingit cache pits were commonly associ-ated with winter villages, they also occurred in summer fish camps (de Laguna 1972, Maschner 1992) and suggest the possibility of undiscovered domestic features nearby. Several Sitka spruce trees have had patches of bark removed by adze or axe. This may have been done to collect pitch or gum. Spruce pitch was used in traditional Tlingit culture as a fire starter, to repair damaged watercraft, and in traditional medicine (Thornton and Hope 1998, Sitka Tribe of Alaska Kayaani Commission 2006). Most of the trees are believed to be less than 200 years old, indicating continued use of traditional medicines through the historic period.

Summary

The inventory at Sitka National Historical Park is the first in this part of southeastern Alaska to intensively study an area along an important salmon fishing tribu-tary. Eighteen sites were recorded within an 112-acre area of rainforest. Ten of these reflect occupation by prehistoric Native Americans and their descendants, the Sitka Tlingit and the Kiks.ádi clan, from 2,600 years ago to the modern era. Archeologists identified the 1804 Tlingit-Russian battleground and refined the probable location of the Tlingit fort to an area within or adjacent to the Fort Clearing. Archeological research at Sitka has provided insights into prehistoric manufacture and utilization of opportunistic tools, site distributions, and food preparation. Finally, the project confirmed the viability of a multidimensional approach to archeological research by combining information from fieldwork, oral and written history, and the natural sciences to create a more holistic interpretation of past lifeways.

Acknowledgements

The 2005-2008 Sitka National Historical Park inventory was funded through the NPS Systemwide Archeological Inventory Program. The project’s success was due to the efforts of many individuals, but particularly Chief of Resource Management Gene Griffin. It concluded Gene’s nearly 30-year initiative to document park cultural and natural resources, a process that involved historians, oral historians, geologists, geophysicists, ecologists, soils scientists, archeologists, cultural landscape architects, and botanists from 12 tribal, federal, state, and private organizations. These investigations led to a broad understanding of the park’s natural and cultural history from circa 4,500 years ago when the park lands emerged from the sea through the twentieth century. Although Gene retired shortly after the fieldwork was completed in 2008, his legacy will be of great importance to park planning, interpretation, and research for decades to come.

References

Chaney, G.P., R.C. Betts, and D. Longenbaugh. 1995.

Physical and Cultural Landscapes of Sitka National Historical Park, Sitka, Alaska. Unpublished report prepared for the National Park Service, Sitka National Historical Park.

Davidson, A. 1999.

Orach. In The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. New York.

Davis, S. (editor). 1989.

The Hidden Falls Site, Baranof Island, Alaska. Aurora Alaska Anthropological Association Monograph Series V. Alaska Anthropological Association. Fairbanks, Alaska.

Davis, S. 1990.

Prehistory of Southeastern Alaska. In Northwest Coast, Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 7, pp. 197- 202. Edited by Wayne Suttles. Smithsonian Institution. Washington D.C.

de Laguna, F. 1972.

Under Mount Saint Elias: The History and Culture of the Yakutat Tlingit. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, Vol. 7. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C.

Emmons, G.T. 1991.

The Tlingit Indians. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. Edited and additions by and Frederica De Laguna. University of Washington Press. Seattle, WA.

Hadleigh-West, F. 1959.

Exploratory Excavations at Sitka National Monument. Unpublished report prepared by the University of Alaska for the National Park Service, Contract num-ber 14-10-434-210. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Sitka National Historical Park. Sitka, Alaska.

Krieckhaus, B., R. Foster, and S. Trull. 1993.

Ecological Inventory: Sitka National Historical Site. Unpublished report prepared for the National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office under Interagency Agreement No. IA 97070-2-9017 by U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Tongass National Forest.

Lisiansky, U. 1814.

A Voyage Round the World in the Years 1803, 4, 5, & 6; Performed by Order of His Imperial Majesty Alexander the First, Emperor of Russia in the Ship Neva. Printed for John Booth; and Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown. London.

Lisianskii, I. 2008.

Eyewitness Account of the Battle of 1804 and Peacemaking of 1805. Translated by Lydia T. Black. In Anóoshi Lingít Aaní Ká, Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804, edited by Nora M. Dauenhauer, Richard Dauenhauer, and Lydia T. Black. University of Washington Press. Seattle.

McNab, W.H., and P.E. Avers. 1994.

Section M245B-Northern Alexander Archipelago. In Chapter 27, Ecological Subregions of the United States. Prepared in cooperation with regional compilers and the ECOMAP team of the Forest Service. (http://www. fs.fed.us/land/pubs/ecoregions/). Accessed September 16, 2008.

Maschner, H.D.G. 1992.

The Origins of Hunter and Gatherer Sedentism and Political Complexity: A Case Study from the Northern Northwest Coast. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. University of California-Santa Barbara. Santa Barbara, California.

Matson, R.G., and G. Coupland. 1995.

The Prehistory of the Northwest Coast. Academic Press. New York.

Newton, R.G., and M.L. Moss. 1984.

The Subsistence Lifeway of the Tlingit People: Excerpts of Oral Interviews. USDA Forest Service. Alaska Region Administrative Document No. 131.

Sitka Tribe of Alaska Kayaani Commission. 2006.

The Kayaani Commission Ethnobotany Field Guide to Selected Plants Found in Sitka, Alaska. The Kayaani Commission. Sitka Tribe of Alaska. Sitka, Alaska.

Stewart, H. 1973.

Indian Artifacts of the Northwest Coast Indians. Hancock House Publishers. Blaine, Washington.

Thornton, T.F., and F. Hope. 1998.

Traditional Tlingit Use of Sitka National Historical Park. Unpublished report prepared under NPS Contract #1443PX970095345 for Sitka National Historical Park. Sitka, Alaska.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 10 Issue 1: Connections to Natural and Cultural Resource Studies in Alaska's National Parks.

Last updated: July 17, 2018