The Iñupiat and Athabaskan people who lived and traveled in the Arctic lands now in Alaska’s National Park System had names for natural features such as rivers, mountains, bays; human settlements and trails; and places to hunt, fish, and gather. The indigenous names are rich ethnographic and historical resources. Many of them refer to activities that regularly took place at the site; others tell of historical events that occurred there. Although the names were preserved in oral tradition, they have been replaced with English names on modern maps. Many of the elders who knew the place names and their stories are now gone; it is urgent to document the knowledge of those still living.

NPS Photo / Eileen Devinney

Communities and scholars show a growing interest in documenting indigenous place names. Place name research can help archaeologists and historians by tying place names to prehistoric and historic sites. Connecting place names with the broader ethnographic record increases our understanding of how Alaska Natives used the landscape.

Previous National Park Service (NPS) place name projects, such as one supporting the Northwest Arctic Native Association (NANA) Museum of the Arctic, depended on the extensive local knowledge, often from a single person; Joe Immaluraq Sun of Shungnak (1900-1993) was one such person. David Libby interviewed Joe Sun in the early 1980s to record his life history and place names information for the upper Noatak and northwest Alaska. The resulting report, Place Names on the Upper Noatak and Contiguous Areas, listed 121 place names.

Qamani: Up the Coast, In My Mind, In My Heart is an unpublished monograph Susan Fair co-authored with Edgar Nunageak Ningeulook for Bering Land Bridge National Preserve in 1995. It includes place names with their stories and histories along the coast near Shishmaref. In 2016, Bering Land Bridge started Qamani, Volume 2, a study of place names along the coast near the village of Wales.

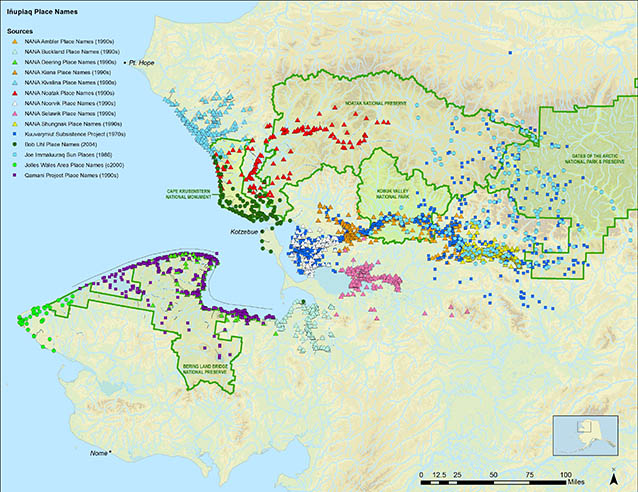

Most of the Alaska Native place name projects also include maps. The Iñupiaq Place Names Project, partially funded by the NPS Tribal Grants Program, began in the early 1990s. For a number of years, anthropologist Eileen Devinney and Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve staff have consolidated Iñupiaq place names from several projects onto a single map.

Recently, Gates of the Arctic National Park assisted the Simon Paneak Museum in Anaktuvuk Pass to compile and map local Iñupiaq place names. The park has also documented Nunamiut (inland Iñupiaq) place names in the Killik and Nigu River drainages, recording oral history and stories associated with these places. Working with the Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, they translated place names on the 1900 George Stoney map of northwestern Alaska, a seminal historic place names map that had not previously been given much linguistic attention.

Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve initiated a project in partnership with the Yukon Native Language Centre for Han place names around Eagle Village and the preserve.

Place names may have many levels of meaning, and multiple stories attached to them. The next step is to make information about Alaska Native place names more accessible to Alaska Native communities, park managers, and the public.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 16 Issue: Science in Alaska's Arctic Parks.

Last updated: September 21, 2017