Courtesy Joel Berger

When you go to a natural history museum, you see the past, including extinct species such as dinosaurs or mammoths. You might view some that are still present, too, such as penguins or polar bears. What you’ll not see is the future, which is determined by a combination of environmental change and human behavior, the latter is at times difficult to predict. Under the right circumstances, one can look to the past and imagine a future, even a brighter one.

People entered the New World about 13,000 years ago, most crossing a massive land bridge that connected Asia to America. Some of that connection is now under water, the oceans above teeming with more than 150,000 walrus, nearly 20,000 bowhead whales, and uncounted number of seals. The region, known as Beringia, offers critical summer habitat for 280 migratory bird species from every continent and, importantly, is the permanent home for caribou, snow sheep, wolves, and polar bears. It’s also where there’s a shared responsibility for the proud and natural heritage of both Russia and the United States. It’s where both Presidents Putin and Obama visited their respective sides of the remote Chukchi Sea and the doomed land bridge. Science and conservation have perhaps more sunny prospects in this sensitive geo-realm given a collaboration that reaches back in history, continues, and is fueled by joint interests in a mammoth-like beast, one with thick luxuriant fur that drapes like a skirt to the ground—the muskoxen.

Neither maker of musk or an oxen, this misnamed species was driven to extinction in Arctic Alaska by the late 1800s. The downward spiral began with the introduction of guns when Alaska was still managed by Russian dominance from St. Petersburg, and before the land was purchased by Washington in 1867. Governance and conservation often go hand in hand, and international diplomacy can be and has been packaged in creative shapes. Animals play roles that transcend symbols and lovability.

Among the most heralded displays of diplomacy occurred during a tense era when the world’s super powers were hardly speaking (1972). That’s when a colorful gift, jostling pandas, arrived in the U.S. following President Richard Nixon’s historic visit to Beijing. Nixon followed in turn with the gift of an Arctic regal and its largest land animal, one whose fur-ball babies outrival panda cubs for cuteness: two muskoxen, a species the world has truly yet to recognize, let alone embrace. Cooperation follows unpredictable paths.

The year following Nixon’s 1974 resignation, the U.S. government took a further step, but not with China. On behalf of Moscow, it flew muskoxen from Alaska to Russia to establish a wild population in northern Siberia. The locale, Wrangel Island, is the Arctic’s only World Heritage Site. It’s also where I continue to work with committed Russian biologists and with support from both governments. While international conservation successes are not especially frequent, panda diplomacy and polar bears are useful tokens. The true unsung heroes in this case are muskoxen.

A 1968 essay, On War and Peace in Animals and Man, written by 1973 Nobel Laureate Niko Tinbergen, touted neither diplomacy nor animal heroes. He argued we need to offer a gentler world. Neither Tinbergen nor President Nixon knew much about biodiversity, but both realized that environment and animals matter. So does President Putin. While it’s too early to judge the commitment the new U.S. administration will have to Arctic conservation, former President Obama’s 2015 visit to Kotzebue on the Chukchi shoreline is further testimony that local culture, food security, and climate all connect.

The fact that the Russian government enables biological investigations to continue on a remote frozen isle is one thing; more relevant is that the misnamed muskox is an eerie success story, one that unites a conservation mission crossing five northern countries, the scale of which dwarfs the marveled recoveries of North American bison and Yellowstone wolves. The true-to-life saga for success was reignited when pre-statehood Alaska’s 1930 funding request for an ambitious re-introduction was approved by the U.S. Congress. Wild muskoxen were most accessible then in Greenland, and the challenge was how best to capture and transport the helmeted warriors with lethal upturned horns and whose defensive groups are reminiscent of modern elephants or their now-extinct comrades, the wooly mammoths. Greenland hunters solved the problem: they killed adult moschus, nabbed the wailing babies, and sent them by ship to Norway. From there, they voyaged across different oceans, arriving by ship to shores near the Bronx Zoo. Then the real journey began.

Animals were loaded in railroad cars and moved by train 2,500 miles to Seattle; from there it was only 1,400 miles by boat to Seward, Alaska; and then a mere 486 miles by rail to Fairbanks. Youngsters were later floated hundreds of miles down the Yukon and Tanana Rivers to the Bering Sea, and then just a short 20-mile hop across choppy open seas to Nunavik Island.

Forty more years passed and the progeny from the original Greenland transplant were airlifted to sites throughout Alaska’s Arctic. Today, the wild Alaskan population numbers more than 4,000; Siberia now has even more. My continuing efforts are with Russian scientists from Chukotka’s Autonomous Region including the director of Wrangel Island Reserve, Dr. Alexander Gruzdev, where our science and conservation goals target two topics.

The first is how we establish ecological baselines so that it’s possible to understand the nature of change. If we don’t know the past, we can’t say there is change. In this case, we’re engaged in photogrammetry, the science of photo-imaging, as a technique to chart muskoxen physical parameters in relationship to potential environmental drivers. We’re measuring the head dimensions of young muskoxen, which are sensitive to nutrition. We can assess growth rates as they are linked to weather and food (Berger 2012). In the spirit of bilateral cooperation, Gruzdev came from Moscow to Montana in 2012 and then Yellowstone for initial familiarizations with the approach, techniques, and then we followed up with my work and capacity building with his staff on Wrangel.

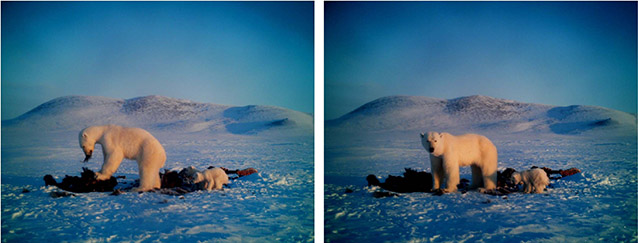

The second target is focused on the changing nature of nature, that is, the predator-prey relationships between bears and muskoxen, some of which indirectly involves people. The idea is simple; with more male muskoxen harvested for meat or trophy, herds have an increasingly biased sex ratios (i.e., fewer males; Schmidt and Gorn 2013), yet males might be important arbiters of effective herd defense, or there may be other factors affecting juvenile recruitment. Few empirical data on predator-prey dynamics are available; we’re unsure if relationships are changing, especially in places like Wrangel.

In Alaska, grizzly bears are increasingly viewed as a potential agent governing muskoxen population trends. Polar bears, too, prey on muskoxen. My work in both Russia and the U.S. is to improve our understanding of how muskoxen might fare when encountering bears, either white or brown, when herds vary in composition, some with bulls and some without.

Courtesy Olga Starova

Science is one thing, geopolitics quite another. What does cold war and collapsed land bridges, warming temperatures, and muskoxen have to do with the realpolitik of diplomacy? Much.

It’s about life on this planet; one of limited resources and countries trying to do better for their people. Critically, it’s also about animals and the systems that support them, and us. Beasts of nature’s creation carry meaning beyond breath and blood or a slab of meat tossed on the dinner table. They can be amulets of peaceful unification or for ecological restoration and food security. The gift of the misnamed moschus transcends the polar sovereignties of Canada, the U.S., Norway, Denmark, Greenland, and Russia. If differences are set aside for a broader good, animals benefit, and so do people.

Neither the U.S. nor Russia has wild pandas, but there are polar bears and muskoxen, and other wildlife and a commitment to protect them, to share knowledge, and to infuse conservation in the global community because biodiversity is at the core of every country’s heritage and should be its future. Icons like pandas and polar bears help raise issues that affect all of us—governance and ecosystems, climate and international relations. The offering of moschus, a species clearly in need of a new name, is both symbol and reality. Understanding people without animals is to divorce us from our past. Seeing specimens in a museum can be fascinating and inspirational; likewise conserving living species while understanding the past is a prudent entry to a better future.

Courtesy Joel Berger

References

Berger, J. 2012.

Estimation of body-size traits by photogrammetry in large mammals to inform conservation. Conservation Biology 26:769-777.

Schmidt, J. H. and T. S. Gorn. 2013.

Possible secondary population-level effects of selective harvest of adult male muskoxen. PloS One 8(6):e67493.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 16 Issue: Science in Alaska's Arctic Parks.

Last updated: March 6, 2017