Last updated: January 26, 2022

Article

Analyzing Early Driftwood Houses of Coastal Alaska

By Claire Alix and Owen K. Mason

Early indigenous semi-subterranean houses of coastal Alaska are traditionally made from a driftwood frame and whalebone, covered with sod and turf (Lee and Reinhardt 2003). Such houses are found on both sides of the Bering Strait and date back at least 3,000 years. In the 1950s, archeologist James Louis Giddings uncovered unique wooden frame houses associated with Old Whaling tool assemblages (Giddings and Anderson 1986) at Cape Krusenstern. These old houses were built using a series of regular upright posts with large rooms connected to small alcoves that were entered through short tunnels.For thousands of years, driftwood continued to be an essential architectural material for these houses. The best-preserved archaeological houses are found on the western, northwestern and northern coasts of Alaska and St Lawrence Island. In the last 1500 years, these houses were associated with the Ipiutak, Birnirk, Punuk and Thule archaeological cultures. Materials used in house construction varied. The ratio of wood vs. slabs of stones, boulders and/or whalebone is related to available raw materials and changes in driftwood at any given place and time (Mason 1998). However, the use and incorporation of whalebone in the house frames may have also been driven by the importance of whales in those cultures (see for ex. Alix et al. 2018).

Images courtesy of The Cape Espenberg Birnirk Archaeology Project

Images courtesy of The Cape Espenberg Birnirk Archaeology Project

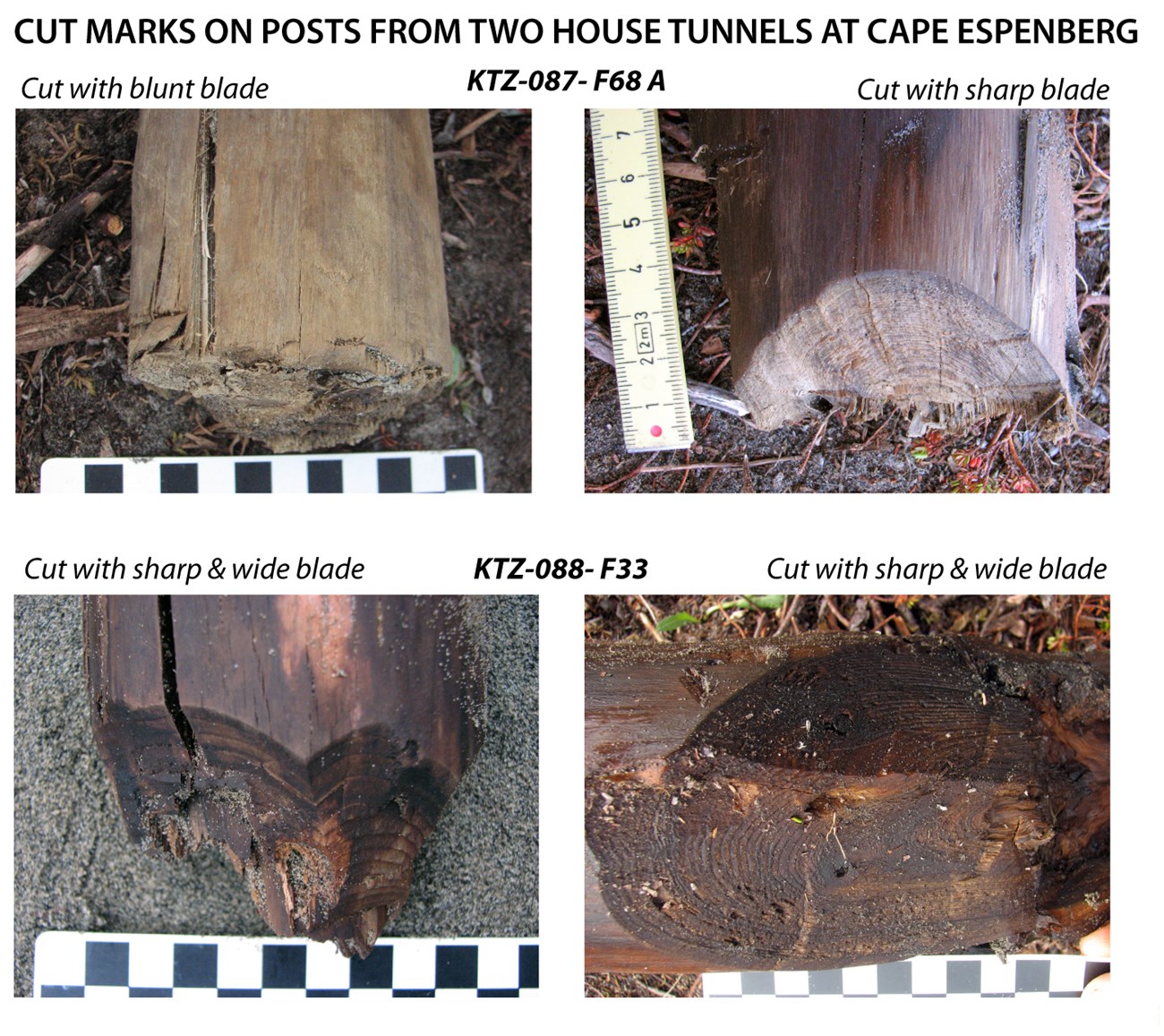

In the earliest excavated houses, driftwood logs were large and often unsplit. Logs were split for flooring or benches. Walls were made of large horizontally stacked logs supported by posts; log diameters varied between 40 and 15 cm. In later constructions, log diameters were smaller, and posts and other structural elements were more commonly split. At the same time, signs of driftwood reuse are more common. Wood identification and tree-ring analyses show that logs were cut and split to be placed in different areas of the house (Norman et al. 2017) and with time, the use of willow and poplar increased over spruce as major structural elements. For example, in the youngest excavated house, the frame of the tunnel is built with small diameter (ca. 11 cm) and mostly split upright posts rather than horizontal full logs (see also Méreuze 2015).

Images courtesy of The Cape Espenberg Birnirk Archaeology Project

The preservation of driftwood at these coastal sites in Alaska and in the Arctic is unique for archaeology, and reflects a long knowledge of the material and accomplished craftsmanship (Alix 2016). The excavation and detailed recording and analysis is necessary to better understand changes in access to and availability of driftwood and the change or continuity of preferential choices and wood technology through time.

This research is funded by the National Science Foundation, Arctic Social Program - Grants # ARC-1523160 to C. Alix & N.H. Bigelow at the University of Alaska Fairbanks [AQC]; ARC-0755725 to J.F. Hoffecker & O.K. Mason and ARC-1523205 to O.K. Mason at the University of Colorado Boulder [INSTAAR] and by a grant from the Archaeology Commission of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs to C. Alix at Paris 1 Pantheon Sorbonne

University)

Cited references

Alix, Claire

2005 Fieldnotes - Cape Woolley and King Island Project. Note de Terrain en possession de l’auteur.

2016 A Critical Resource: Wood use and technology in the North American Arctic. Edited by T. Max Friesen and Owen K Mason. The Oxford Handbook of the Prehistoric Arctic:109–129. DOI:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199766956.013.12.

Alix, Claire, and O.K. Mason

2018 Birnirk Prehistory and the emergence of Inupiaq culture in northwestern Alaska - Archaeological and Anthropological perspectives - Field Investigation at Cape Espenberg 2017. Unpublished Annual Report to the National Park Service US Department of the Interior. Fairbanks, Alaska.

Alix, Claire, Owen K. Mason, and Lauren E. Y. Norman

2018 Whales, wood and baleen in northwestern Alaska - Reflection on whaling through wood and boat technology at the Rising Whale site. In Whale on the Rock II, pp. 41–68. Ulsan Petroglyph Museum. Ulsan Petroglyph Museum, Ulsan Metropolitan City, South Korea.

Alix, Claire, Owen K Mason, Lauren E.Y. Norman, Nancy H. Bigelow, and Chris V. Maio

2017 Birnirk prehistory and the emergence of the Inupiaq culture in northwestern Alaska - archaeological and anthropological perspectives - Field investigations at Cape Espenberg, 2016Unpublished Annual Report to the National Park Service US Department of the Interior. University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Giddings, James Louis

1941 Dendrochronology of Northern Alaska. Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research Bulletin. Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, Tucson.

1952 The Arctic woodland culture of the Kobuk River. University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Giddings, James-Louis, and Douglas D. Anderson

1986 Beach Ridge Archeology of Cape Krusenstern. National Park Service, Washington.

Hoffecker, John F, and Owen K Mason

2010 Human Response to Climate Change at Cape Espenberg: 800-1400. Field investigations at Cape Espenberg 2010 -Unpublished Preliminary Report to the National Park Service - US Department of the Interior. Preliminary Report to the National Park Service - US Department of the Interior. Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder Colorado.

2011 Human Response to Climate Change at Cape Espenberg: AD 800 - 1400, Field Investigations at Cape EspenbergUnpublished Annual Report to the National Park Service US Department of the Interior. Boulder, Colorado.

Lee, Molly, and Gregory A. Reinhardt

2003 Eskimo architecture : dwelling and structure in the early historic period. University of Alaska Press : University of Alaska Museum, Fairbanks.

Mason, Owen K.

1998 The Contest between the Ipiutak, Old Bering Sea, and Birnirk Polities and the Origin of Whaling during the First Millennium A.D. along Bering Strait. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 17(3):240–325.

Méreuze, Rémi

2015 La construction de la maison 33 du cap Espenberg, nord-ouest de l’Alaska, au XVIIIe siècle. Les Nouvelles de l’Archéologie 141:19–25.

Méreuze, Rémi, and Claire Alix

2016 Identifier des techniques de travail du bois chez les Inuit grâce à la photogrammétrie et la réalité virtuelle. Les Nouvelles de l’Archéologie 146:33–39.

Norman, Lauren E.Y., T. Max Friesen, Claire Alix, Michael J.E. O’Rourke, and Owen K Mason

2017 An early Inupiaq occupation: observations on a Thule house from Cape Espenberg, Alaska. Open Archaeology 3:17–49.

Raymond-Yakoubian, Julie, Yury Khokhlov, and Anastasiya Yarzutkina

2014 Indigenous Knowledge and Use of Bering Strait Region Ocean Currents. Kawerak Inc.

Alix, Claire

2005 Fieldnotes - Cape Woolley and King Island Project. Note de Terrain en possession de l’auteur.

2016 A Critical Resource: Wood use and technology in the North American Arctic. Edited by T. Max Friesen and Owen K Mason. The Oxford Handbook of the Prehistoric Arctic:109–129. DOI:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199766956.013.12.

Alix, Claire, and O.K. Mason

2018 Birnirk Prehistory and the emergence of Inupiaq culture in northwestern Alaska - Archaeological and Anthropological perspectives - Field Investigation at Cape Espenberg 2017. Unpublished Annual Report to the National Park Service US Department of the Interior. Fairbanks, Alaska.

Alix, Claire, Owen K. Mason, and Lauren E. Y. Norman

2018 Whales, wood and baleen in northwestern Alaska - Reflection on whaling through wood and boat technology at the Rising Whale site. In Whale on the Rock II, pp. 41–68. Ulsan Petroglyph Museum. Ulsan Petroglyph Museum, Ulsan Metropolitan City, South Korea.

Alix, Claire, Owen K Mason, Lauren E.Y. Norman, Nancy H. Bigelow, and Chris V. Maio

2017 Birnirk prehistory and the emergence of the Inupiaq culture in northwestern Alaska - archaeological and anthropological perspectives - Field investigations at Cape Espenberg, 2016Unpublished Annual Report to the National Park Service US Department of the Interior. University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Giddings, James Louis

1941 Dendrochronology of Northern Alaska. Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research Bulletin. Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, Tucson.

1952 The Arctic woodland culture of the Kobuk River. University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Giddings, James-Louis, and Douglas D. Anderson

1986 Beach Ridge Archeology of Cape Krusenstern. National Park Service, Washington.

Hoffecker, John F, and Owen K Mason

2010 Human Response to Climate Change at Cape Espenberg: 800-1400. Field investigations at Cape Espenberg 2010 -Unpublished Preliminary Report to the National Park Service - US Department of the Interior. Preliminary Report to the National Park Service - US Department of the Interior. Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder Colorado.

2011 Human Response to Climate Change at Cape Espenberg: AD 800 - 1400, Field Investigations at Cape EspenbergUnpublished Annual Report to the National Park Service US Department of the Interior. Boulder, Colorado.

Lee, Molly, and Gregory A. Reinhardt

2003 Eskimo architecture : dwelling and structure in the early historic period. University of Alaska Press : University of Alaska Museum, Fairbanks.

Mason, Owen K.

1998 The Contest between the Ipiutak, Old Bering Sea, and Birnirk Polities and the Origin of Whaling during the First Millennium A.D. along Bering Strait. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 17(3):240–325.

Méreuze, Rémi

2015 La construction de la maison 33 du cap Espenberg, nord-ouest de l’Alaska, au XVIIIe siècle. Les Nouvelles de l’Archéologie 141:19–25.

Méreuze, Rémi, and Claire Alix

2016 Identifier des techniques de travail du bois chez les Inuit grâce à la photogrammétrie et la réalité virtuelle. Les Nouvelles de l’Archéologie 146:33–39.

Norman, Lauren E.Y., T. Max Friesen, Claire Alix, Michael J.E. O’Rourke, and Owen K Mason

2017 An early Inupiaq occupation: observations on a Thule house from Cape Espenberg, Alaska. Open Archaeology 3:17–49.

Raymond-Yakoubian, Julie, Yury Khokhlov, and Anastasiya Yarzutkina

2014 Indigenous Knowledge and Use of Bering Strait Region Ocean Currents. Kawerak Inc.