Part of a series of articles titled World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska.

Article

World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska - Chapter 2: Funter Bay Cannery, pt. 1

Right: Alaska State Library C.L. Andrews collection PCA45-124

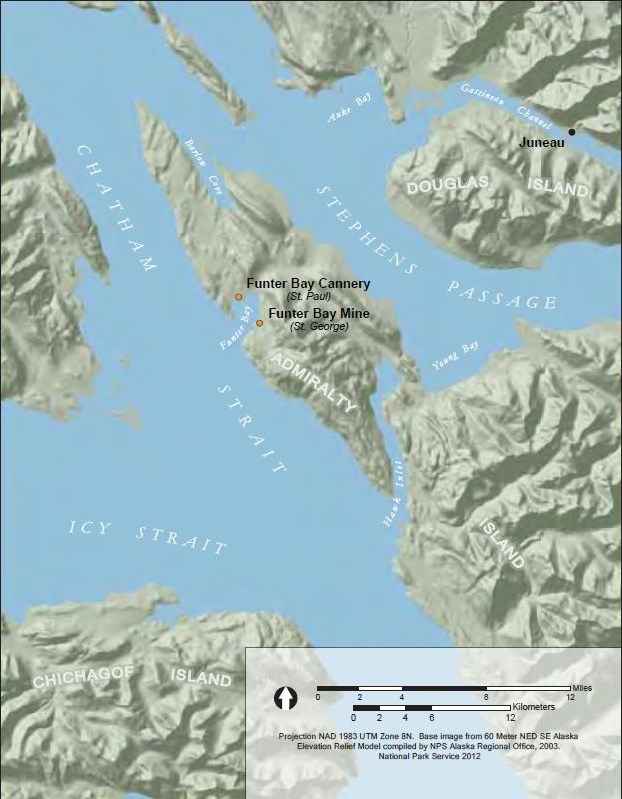

The villagers of St. Paul spent most of World War II at the Thlinket Packing Company cannery at Funter Bay. The cannery site is on a small peninsula projecting southwest into Funter Bay, on the Mansfield Peninsula at the northwest end of Admiralty Island (Figures 8-9). The land consists of rolling moraine deposits from sea level up to an elevation of almost 500’, punctuated by sheer rock cliffs occurring from sea level up to the Peninsula’s highest point – Robert Barron Peak at 3475’ (Orth 1967:808). The mountain’s peak and upper slopes are above treeline; a thick forest of spruce and hemlock carpets the landscape below to the water’s edge (Figure 8).

Early Years

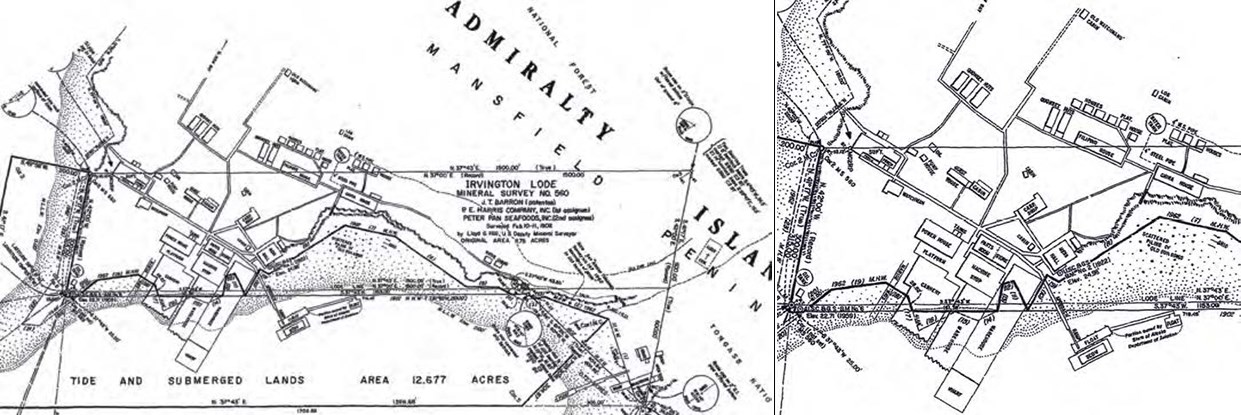

The Mansfield Peninsula is within the traditional territory of the Wuckitan clan of the Auk Tlingit (Goldschmidt et al. 1998:37-44), and Funter Bay had probably long been favored for seasonal fishing (Figure 10). In 1899 Portland banker James T. Barron organized the Thlinket Packing Company (Gaston 1911:88-89) and applied for 11.75 coastal acres on the northwest end of Admiralty Island as a mining claim – the Irvington Lode. Mr. Barron was the father of Robert Barron, for whom the Peninsula’s highest point is named (Orth 1967:808). It’s unlikely that the elder Barron had any intention of mining the claim; he completed the initial $1000 worth of assessment work by excavating a 20’x 40’ hole six feet deep along the shore at what would become a warehouse site, and by digging a 2’ x 2’ “water flume” from a small creek to a point beside the machine shop that would become the cannery’s powerhouse. The land was patented as U.S.Mineral Survey 560 (Hill 1901), and Barron had a cannery built at Funter Bay and was packing fish by 1902 (Cobb 1922:44). That same year a U.S.Post Office was established at the cannery (Orth 1967:357).

Alaska State Library Case & Draper collection PCA39-1002

A warehouse was built in 1906, and during the following year the cannery building was expanded to hold additional machinery (Figure 11), so that by 1907 the facility had the capacity to pack 2,500 cases of pink salmon a year under labels such as “Buster,” “Sea Rose,” “Autumn,” “Peasant,” “Thlinket,” “Tepee,” and “Arctic Belle” (Pacific Fisherman 1907:21). All of the cannery’s fish came from five large commercial fish traps, and the work force consisted of Native, Chinese, Japanese, and EuroAmerican laborers (Kutchin 1906:22).

In 1926 the Funter Bay cannery was sold to the Alaska Pacific Salmon Corporation, which continued packing fish until 1930 or 1931 (Bower 1941:134; MacDonald 1949:32). A fire on May 31, 1929, destroyed “the Oriental bunkhouses and a number of Indian cottages” (Pacific Fisherman 1930:64-65). This was a boom time for Alaska’s fisheries (Cooley 1963:84, 102), particularly in southeast Alaska, and Chatham Strait had major facilities canning, salting, or rendering bottom fish, salmon, herring, and whale (Mobley 1994:30-31;1999:8-18). During the 1930 season the Funter Bay cannery operated with two stationary and 19 floating fish traps (Bower 1931:44). Nonetheless, in 1931 the cannery was closed for what turned out to be forever, due to a water shortage (Colby 1941:149).In 1941 the property was sold to the P.E. Harris Company – a well-known Alaska fish processor from 1912 until 1950 and the predecessor of Peter Pan Seafoods (MacDonald 1949:32).

National Archives document from Zacharof (2002)

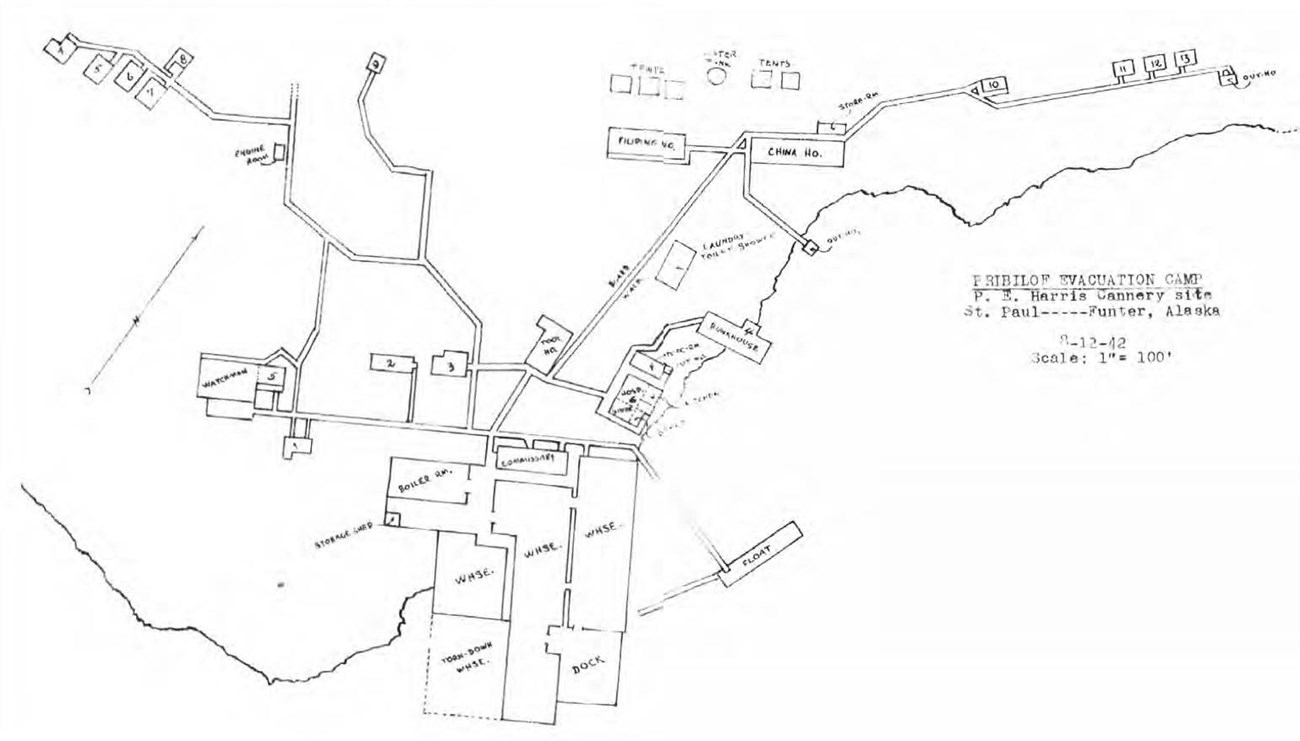

A map made in August of 1942 two months after the Pribilof villagers arrived shows the cannery buildings labeled with their new emergency functions (Figure 12), while a 1962 plat for adjacent Alaska Tidelands Survey 147 plots most of those same pre-war buildings (as well as Quonset huts and small cabins built for the Aleut internment) with their original building titles from the pre-war cannery days (see Figure 25). So each map has functional building labels more appropriate for the other. The industrial buildings were clustered tightly near the south corner of the lot, where a rock promontory juts into deep water and allowed construction of a wharf to serve deep-draft cargo vessels (Figure 13). The wharf connected the fronts of three long buildings extending out from shore – two large warehouses on the east and an even larger 80’-wide cannery building on the west. All three buildings were on pilings and most of their length was over the inter-tidal zone. A 1907 photograph shows a sign on the gable of the left warehouse reading “THE THLINGIT PACKING CO.”

Left: Alaska State Library William Norton collection PCA226-411. Right: Alaska State Library William Norton collection PCA226-412

Attached behind the central warehouse was a machine shop, and across a decked platform behind the cannery was the boiler room, or power house (Figure 14). The power house’s west end protruded past the industrial complex, extending the power train to serve a winch for the marine railway at the intertidal zone. The building was oriented so that overhead belts could transfer power to the cannery in one axis and an overhead shaft could transfer power to the machine shop in the other axis. Two small rectangles on the north side of the power house (labeled TANKS on the plat – see Figure 25) were secondary fuel tanks probably served by the larger wood-stave fuel tank at the property's far south point. The last building of the industrial cluster was divided into a parts room serving the whole complex, and a commissary, or store.

Left: Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Al Cox and Pat Pletnikoff collection. Right: Alaska State Library Vincent Soboleff collection PCA 01-3844

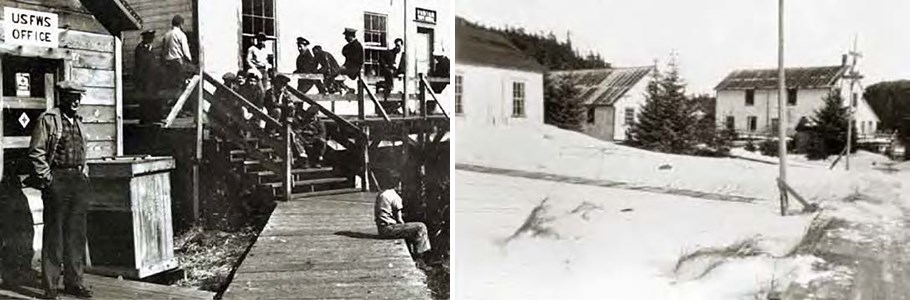

The store opened onto the cannery's main boardwalk and – together with the mess hall and ramp down to the floats – served the citizens of the greater Funter Bay as its social center. Archival photographs allow reconstruction of the layout. The mess hall was a two-story 40' x 50' building almost completely encircled by the boardwalk, and was the first building encountered when walking up from the floats where smaller boats docked. At the south end of the west wall was the entrance to the dining room, below a sign reading "CANTEEN." In the southeast corner of the building was a partitioned room entered through an exterior door below a sign reading "FUNTER POST OFFICE." During the war a small cabin connected to the boardwalk by the mess hall was used as the USFWS office (Figure 15), contributing to the social importance of the building cluster. The next nearest building to the mess hall was the tool headquarters, or carpenter shop, located centrally to serve the entire cannery complex (Figure 16) and still standing in 2008.

University of Alaska-Fairbanks Fredericka Martin collection 91.223.272

Lodging at the cannery during its later years of operation was of several types (as mentioned the Quonset huts and two rows of small houses plotted north of the property line on the 1962 survey are of later wartime construction). The old surveys show some of the building locations, and the archival photographs show some of their architectural details (Figure 17). The superintendent's house was a composite building at the west end of the main cannery boardwalk consisting of a central one-story block with a shed-roofed dormer, attached at the southwest corner to a cross-gabled two-story block, and attached at the northeast corner to another one-story wing. Scaled from the survey, the building enclosed 2,220 square feet of space excluding two porches. Near the superintendent’s house was the watchman’s house – a small one-story home with one north-facing gable-roofed dormer over the entry and another over a window. North of the main boardwalk and connected by a perpendicular boardwalk was a narrow bunkhouse or “Guest House” sharing a porch with a larger frame cabin (used during the war by Father Baranof as his residence).

University of Alaska-Fairbanks Fredericka Martin collection 91-223-350

On the shore northeast of the mess hall was a two-story bunkhouse half on shore and half on pilings over the intertidal zone. Deep in the forest to the north was a small “old watchman’s cabin,” and 200’ to the east was a smaller log cabin. Set off from other buildings almost 200’ to the north were two large two-story bunkhouses,each about 24’ wide and 96’ long, one labeled “Filipino House” (Figure 18) and the other “China House.” Since the cannery’s “Oriental bunkhouses” reportedly burned in 1929, the Filipino and China houses mapped in1942 may have been built immediately that year or the year after to replace the lost housing, because 1930 was the last year of operation. A boardwalk extending along the top of the low coastal bluff northeast of the China House went past a cabin and then a group of three “Native Cabins.” West of the cannery a boardwalk led to a group of five small cabins overlooking Coot Cove, off the cannery lot on USFS property.

University of Alaska-Fairbanks Fredericka Martin collection 91-223-279

Systems serving the cannery complex consisted of water, sanitation, electricity, and the boardwalk. A small creek to the north (near the Aleut cemetery) was dammed with a simple timber crib, from which water was sent via a 4” steel pipe to a large wood-stave tank located between and upslope from the two large bunkhouses. From there at least one smaller line likely ran along the boardwalk to the industrial complex, with spigots along the way. Whether any of the original buildings had independent sewer/septic systems is unknown, but at least three outdoor privies were built out over the intertidal zone. One was attached to a storage shed immediately north of the mess hall, another served the Filipino and China Houses (Figure 19), and a third was located at the far end of the boardwalk past the three Native Cabins. Electricity to individual buildings including dwellings was sent through wires strung on poles, using glass insulators near the tops. Connecting the cannery buildings was a web of plank boardwalks in at least two widths.

After the 1931 closing the owners retained an onsite caretaker who still served as storekeeper and postmaster. A current landowner suggested that a fox-farming or more likely mink-farming operation may have been initiated around that time because of the amount of chickenwire discernible in the early 1990s. But that activity has not been confirmed (since the property was patented land no USFS Special Use Permit would have been needed for a fur-farm, so no archival USFS documentation would necessarily be expected). Chickenwire was a common item at most canneries because it was used for webbing in commercial fish traps. Another explanation for chickenwire features at the Funter cannery is that the caretaker in the 1950s was said to have kept rabbits at the site in chickenwire enclosures.

World War II

When the U.S. entered the war in 1942 the cannery at Funter Bay had not packed fish for over a decade, and the surrounding population attributed to “Funter” was down to about 14 (Colby 1941:149). P.E. Harris Company – the new owner – kept on the company payroll only a caretaker – Harold Hargrave – who lived onsite with his wife and operated the store and post office. Hargrave’s first year on the job was 1941 (The Juneau Empire 1999) and by that time many buildings had fallen into disrepair. The fish packing company was quick to recognize the opportunity for monthly income and had a lease prepared with “THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, hereinafter called the Government,” at a rate of $60 per month, on June 16.The deal was barely struck by the time the Aleuts were underway.

Alaska State Library Butler/Dale collection PCA 306-1093

On June 24, 1942, after a journey of more than a week, the Delarof docked at the cannery and disembarked the entire Native population of St.George and St. Paul villages. Bedding and food from the ship’s stores were discharged along with the villagers’ meager baggage. Two baidars – large (36’) traditional frame boats – had been brought as deck cargo for use at Funter Bay (Figure 20). The two USFWS employees (St. George agent Daniel C.R. Benson and acting St. Paul agent Carl M. Hoverson) and their wives, and the two school teachers from St. Paul – Mr. and Mrs. Helbaum – and their two children, stayed at Funter Bay with the villagers. Other federal employees and their wives, including the two physicians – Drs. Grover and Berenberg – stayed on the Delarof as it cast off that same day and continued to Seattle by way of Killisnoo.

University of Alaska Fairbanks Fredericka Martin collection 91.223.274

The Aleut Experience at Funter Bay

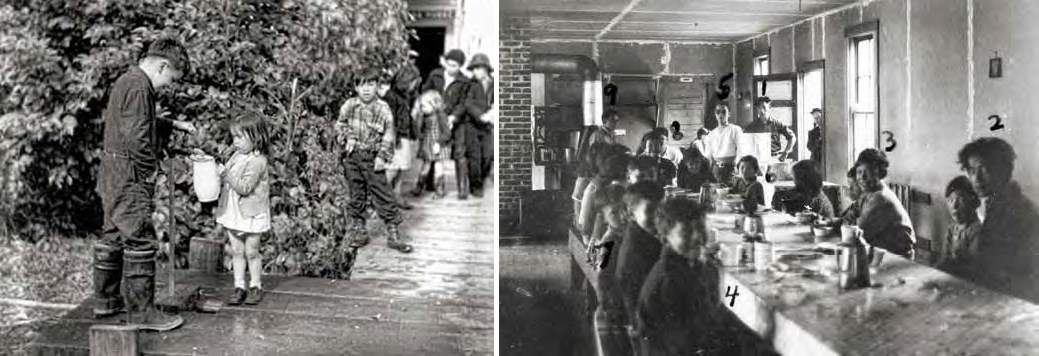

The day after they landed at the cannery, villagers from St. George were shifted to the mine site one mile away. Thereafter, the two Pribilof communities shared the Funter Bay experience from their two respective camps, while the cannery – having the post office, store, and larger dock – continued as the local social center (Figure 21). The St. Paul USFWS agent’s log entry for June 27 to August 2, 1942, describes the basic tasks that all the Aleut evacuee’s faced in making their wartime homes livable: “Entire gang during this period kept busy in constructing bunks, making beds from chicken wire, repairing walks to facilitate traffic, installing electric wiring in various dwellings, repairing leaking roofs, broken windows, rotten flooring, dilapidated outhouses; several men occupied in getting the mess arrangements systemized. Warehouses fixed so that supplies could be locked up….Entire area around the Cannery was surveyed for a possible water supply. Several were found but none met the approval of the Sanitary Engineer. Entire population, both St. George and St. Paul immunized by Mrs. Clara Gaddie, Indian Affairs Nurse….” During the first months after their arrival many families lived in tents; while the agent logged the temperature at 10 degrees above zero on Christmas Eve, 1942, the men were still installing plasterboard walls inside the bunkhouses.

Left: Alaska State Library Butler/Dale collection PCA 306.1092. Right: University of Alaska Fairbanks Fredericka Martin collection 91.223.281

Ordinary domestic tasks became difficult under the circumstances. Potable water was often in short supply due to freezing, poor pipes, inadequate flow, and contamination (Figure 22). Washing clothes must have been an ordeal (Figure 17). Food preparation was made more complicated by the lack of adequate kitchen facilities and familiar subsistence foods (Figure 23).The bunkhouses and cabins were not intended for winter occupancy, so they had no insulation or heating stoves. Agency officials reporting on the poor living conditions had limited success in obtaining needed food, medicine, and supplies.

Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association (copy print, source unknown)

The two communities continued to operate under the direction of their USFWS agents at Funter Bay as they had at their villages. Work parties were organized, and the men were expected to unload supply ships that came to dock. The USFWS’s Penguin served the two Funter Bay camps, as did the agency’s smaller vessels Brant, Crane, Swan, and Heron, and eventually their boat Scoter was assigned to winter at Funter Bay. Port calls were made by the USFS Ranger 6 and 7, fishing boats, fish-buying boats like the King Fisher, the mail boat Estebeth (Figure 24), and YP Boats (vessels in southeast Alaska’s fishing fleet that had been converted – often with original captains and crews – for submarine detection and coastal surveillance). Sometimes a float plane would fly in from Juneau. Villagers took jobs with some of these boats, or went to Juneau to work, but usually between 45 and 60 Aleut men were working at the camp each weekday during the first months of the internment. Teams of as many as two dozen men went salmon fishing to feed the community, or clamming, and hunters would sometimes bring in three or four deer at a time. Eventually a USFWS boat arrived to issue them hunting licenses.

Dr. Berenberg returned to Funter Bay to treat his patients. There were several births in the camps in late 1942. People with severe dental problems went to Juneau for treatment. Islanders with tuberculosis were sent to the Juneau hospital, and sometimes Seattle, when their condition worsened. Soon the need for an Aleut cemetery was grimly acknowledged at Funter Bay, and a small almost-level plot was selected up a protected draw east of the cannery, near the dam built to supply water to the facility. Despite the hardship and death at the Funter Bay camps, the St. Paul and St. George villagers resolutely faced them as they faced hardship and death in the Bering Sea. It is a tribute to the Aleut communities that their children were somewhat shielded from the brunt of the deprivations. Pribilof elders interviewed in the 1990s and 2000s were children at Funter Bay, and most remember a successful childhood adapted to the new surroundings. In mid-October of 1942 the children of the Pribilofs were sent with their federal teachers and their teachers’ families to Wrangell where they attended classes at the Wrangell Institute.

Wartime Construction

The two large bunkhouses were not sufficient to house the entire community of St. Paul, and tents supplementing the housing arrangement weren’t adequate for winter conditions. The 1942 plat shows a pair and another trio of tents north of the China House. The USFWS agent’s logs indicate construction of new “cottages”in late 1942, likely represented on the 1962 survey by a row of three small buildings north of the China House, and an offset row of six small buildings north of the Filipino House (Figure 25). Also constructed during the war, probably in 1943, were a pair of Quonset huts just south of the Filipino House and a group of three further south (Figure 26). Quonset huts were prefabricated round-roofed 16’ x 36’ buildings of corrugated sheet metal panels affixed to curved angle-iron ribs, manufactured by the tens of thousands for Allied military applications and intended to house “10 enlisted men or 5-7 officers” (Decker and Chiei 2005:14). Each of the two groups of Quonset huts had their buildings’ gable walls aligned to face a boardwalk.

Left: Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Fr. Michael Lestenkof collection. Right: Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Fr. Michael Lestenkof collection

In keeping with their devout Russian Orthodox practices, the St. Paul villagers erected two large wall tents on a platform with plank walls to serve as a temporary chapel, according to a photograph taken by Father Michael Lestenkof. Yet another image from his collection, at the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, shows a new but small one-story wood frame chapel, painted white (Figure 27).

New construction mentioned in the USFWS agent’s logbook also includes a water pipeline – probably from the small impoundment near the Aleut cemetery. Sometime after August of 1942 a small gable-roofed building was erected (or perhaps relocated) along the boardwalk near the mess hall as the USFWS headquarters (Figure 15).

According to Zacharof (2002), one of the last acts by departing villagers was to dismantle their hastily built school, church, and pumphouse to build shipping crates for the journey home.

Post-War Development

The Funter Bay cannery stayed in the hands of the P.E. Harris Company after the war ended, and Harold Hargrave continued on as watchman. When the P.E. Harris Company became Peter Pan Seafoods, in about 1962, the new company continued to hold the old cannery property. Hargrave obtained a Special Use Permit from the U. S. Forest Service in 1951 for a residence, dock, and warehouse (also used as a boat house and net house) on the far east end of the cannery complex, according to files at the National Archives, and he and his wife Mary lived at Funter Bay until 1983 when they moved to Juneau (The Juneau Empire 1999). The cannery buildings continued to deteriorate through the 1950s, and by 1961 the seaward side of the industrial buildings was almost completely gone (Figure 28).

Bob DeArmond photograph courtesy

of Patricia Roppel

Peter Pan Seafoods owned the cannery during the 1960s and filed for the adjacent intertidal and submerged land as Alaska Tidelands Survey 147 in 1962. By then the bunkhouse along the shore immediately north of the mess hall was completely gone, marked only by a “scattered piling of old buildings” (Figure 25). According to USFS records, in the early 1960s while Peter Pan Seafoods was operating a major facility at nearby Hawk Inlet, they attempted to evict Hargrave from the Funter Bay cannery because some of Hargrave’s improvements were on cannery property rather than USFS land as permitted. Apparently USFS was able to negotiate quick satisfaction for all parties when it became known, too, that some of the cannery’s buildings were actually north of the cannery’s lot line on USFS land.

As part of a package sale the Funter Bay cannery was conveyed along with several other properties to the Bristol Bay Native Corporation in the 1980s, which in turn sold it to Juneau resident Reed Stoops. Stoops subdivided the property in the early 1990s and together with new owners such as Gordon Harrison hired a local company to demolish and remove or bury most of the derelict cannery buildings. A short system of public floats was built by the State of Alaska to replace the original cannery dock and floats. Funter Bay experienced a resurgence in private residency.

Joe Giefer and his wife Karey Cooperrider were new arrivals, building a home and lodge east of the cannery, and in a 2008 taped interview they described the condition of the cannery buildings in the early 1970s. At that time most of the industrial and domestic buildings were standing and could be cautiously entered, though their rate of deterioration was increasing. After Harold Hargrave disassociated with the cannery and established his adjacent residence, the watchman’s cabin continued as a dwelling for property caretakers – first Scotty Todd, then finally Jim and Blanche Doyle – so it was in good shape at the time. Another small cabin in good condition was used as an overflow guest house by the Doyle family. The superintendent’s house was in good shape except for the roof, and so the building began to disintegrate.

The Quonset huts were still standing, though the interior walls of beaver-board (an obsolete cellulose-panel material) were melting; some had chicken wire arranged by Harold Hargrave to keep rabbits. The small frame cabins built by St. Paul villagers were already lacking roofs in the early 1970s and were in poor condition. Two cliff-side outhouses were still readily distinguishable, one of which was divided into mirror halves, each of which had two or three seats. The pilings under the carpenter’s shop were replaced in the early 1990s with creosote pilings salvaged from the cannery ruin at Hawk Inlet.

Last updated: February 28, 2025