Last updated: March 7, 2023

Article

African American Homesteaders in the Great Plains

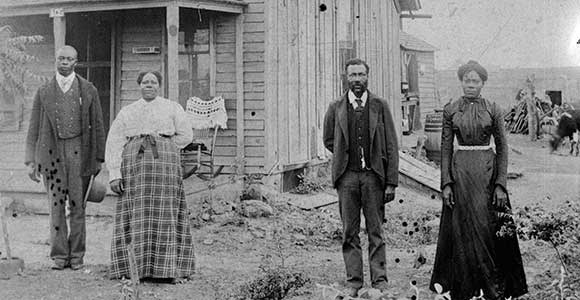

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS KANS,33-NICO,1–6

African Americans successfully homesteaded in all the Great Plains states. While few in comparison with the multitudes of white settlers, black people created homes, farms, a “place,” and a society which were all their own.

A new study, funded by the National Park Service and conducted at the University of Nebraska, sets out in detail the scope and success of black homesteaders in the region. Researchers project that approximately 3,500 black claimants succeeded in obtaining their patents (titles) from the General Land Office, granting them ownership of approximately 650,000 acres of prairie land. Counting all family members, as many as 15,000 people lived on these homesteads.

Black Homesteading

The Homestead Act opened land ownership to male citizens, widows, single women, and immigrants pledging to become citizens. The 1866 Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed that African Americans were eligible as well. Black homesteaders used it to build new lives in which they owned the land they worked, provided for their families, and educated their children. They built meaningful cultural and religious lives for their communities and governed their own affairs themselves—that is, they sought the full benefits of being free and equal citizens.

About thirty percent of black homesteaders filed on federal lands as individuals remote from other African Americans. They had to overcome severe challenges in the harsh climate just to survive. Many persisted and succeeded. They included Oscar Micheaux, who later became a novelist and the first great African American film-maker; George Washington Carver, whose long scientific career and many discoveries while at Tuskegee Institute are justly celebrated; and Robert Anderson, who failed on his first homestead claim but wound up building a prosperous ranch in Nebraska on 2,000 acres.

Learn more about Black Homesteading in America.

Black Homestead Colonies

Most black homesteaders, about seventy percent, settled in clusters or “colonies” with other black families. The most substantial colonies were Nicodemus (Kans.); Dearfield (Col.); Sully County (S. Dak.); DeWitty (Neb.); Empire (Wy.); and Blackdom (N.M.). All these communities have now disappeared, returned to grass, except for Nicodemus, which continues to have residents, and Dearfield, which though abandoned retains a few buildings in great disrepair. Nicodemus is a National Historic Site, and Dearfield is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Residents of these communities struggled to farm successfully in the harsh and drought-prone prairie landscape. Their gamble required immense toil, hardship, sacrifice, courage in the face of long odds, and frequent disappointment. Still, they persisted and were determined to succeed, and they did, achieving their goal of owning land. They also pooled their resources to construct rich cultural and civic lives for themselves: they exuberantly built churches and schools and organized baseball teams, reading circles, choral groups, newspapers, investment clubs, sewing circles, and dances and celebrations.

The researchers at the Center for Great Plains Studies have been reseraching six black homesteading communities in six Great Plains states: Nicodemus, Kansas; DeWitty, Nebraska; Sully County, South Dakota; Empire, Wyoming; Dearfield, Colorado; and Blackdom, New Mexico. These homestead communities are featured in the map below.

About this Study

This epic tale of African American achievement was nearly lost, but descendants of homesteading families, museums like the Great Plains Black History Museum (Omaha) and Black American West Museum (Denver), preservation groups such as the Nicodemus Historical Society and the Dearfield Preservation Committee, and a few scholars and authors kept it alive.

The study was conducted by Richard Edwards, emeritus professor at University of Nebraska, and postdoctoral fellows Mikal Eckstrom and Jacob Friefeld. Dr. Friefeld is now an historian at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, IL. Copies of the study are available from Homestead National Historical Park in Beatrice, Nebraska. Major findings were published in Great Plains Quarterly and are available online.

To learn more about this project and other homestead reserach projects at the University of Nebraska Center for Great Plains Study, visit their Homesteading Research webpage.

Black Homestead Colonies

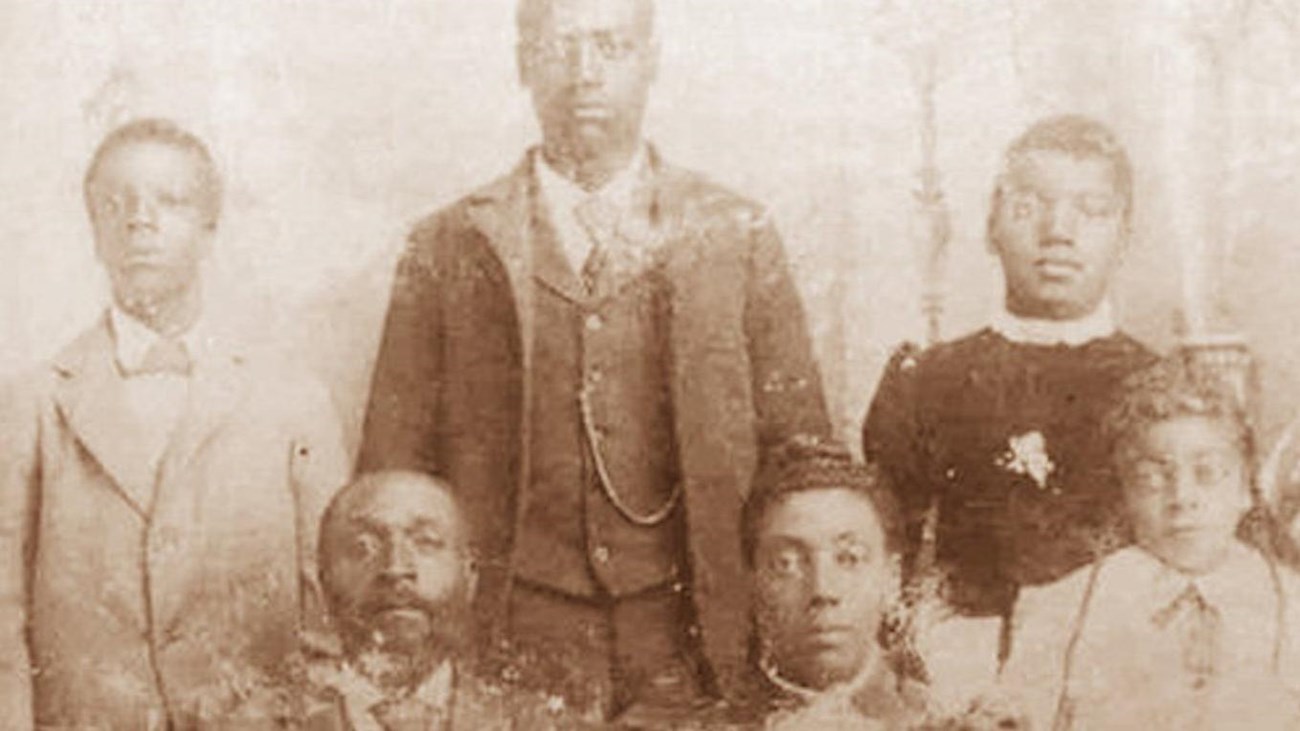

Homesteaders in Black Colonies

Homesteading stories of migration, risk taking, immense toil, hardship, sacrifice, courage in the face of long odds.