Last updated: January 5, 2026

Article

The 1895 National Colored Women's Congress

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

For fifteen weeks starting in the fall of 1895, Atlanta, Georgia hosted the Cotton States and International Exposition. Organizers intended this public fair to showcase the “New South” as a modern, economically diverse, and racially harmonious region. They hoped to encourage sectional reconciliation in the post-Civil War years, to spur further investment in the area, and to promote international trade.[1]

The exposition is most known as the place where Black leader Booker T. Washington gave his “Atlanta Compromise” speech. Like the attitudes of the fair’s White organizers, Washington’s speech highlighted the merits of segregation which he saw as key to the peace and progress of the region. He urged African Americans to seek economic security through work and industrial education, rather than push for political and social rights and equality.[2]

Not all Black attendees, however, adhered to Washington’s accommodationist beliefs.

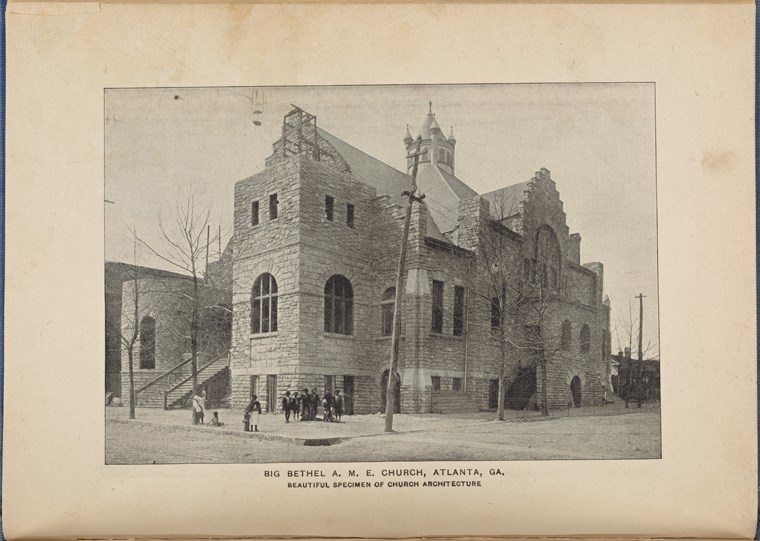

For example, the National Colored Woman’s Congress offered a far more militant tone and damning critique than Washington. Held at the Bethel African Methodist Church during the final week of the exposition, this multi-day conference drew “150 leading and representative women of the race” from across the country.[3] Speakers included “lawyers, teachers, physicians, lecturers, journalists, authors, principals and instructors” including Fannie Barrier Williams, Victoria Earle Matthews, and Margaret Murray Washington.[4]

“In a much more explicit fashion than the men did at the fairs,” wrote historian Nathan Cardon, “African American women vocally took a stand against the South’s racial order.”[5] For example, the National Colored Woman’s Congress issued a series of strongly worded resolutions calling for Southern change. They denounced the convict lease program, a system of forced labor that allowed states to lease prisoners to private citizens for a profit, and called on Southern leaders to reform this widespread practice. They called out racist propaganda and demanded that the press uses titles such as “Mrs.” and “Miss” when writing about Black women. Attacking segregation on public transportation, they pressed for 1st and 2nd class accommodations to protect all women from insult, harassment, and worse.[6]

In perhaps their strongest denunciation of Southern racial oppression, the National Colored Woman’s Congress targeted the ever-present and growing racialized violence towards African Americans. They said:

WHEREAS, all tendency toward mob rule, lynching, burning, midnight marauding, and all unlawful and unjust discriminations, is not only contrary to the fundamental principles of our government, but a menace to every department of justice and the well being of posterity,

Resolved, That we condemn every form of lawlessness and miscarriage of justice, and demand, without favor or compromise, the equal enforcement of the law for all classes of American citizens.[7]

In addition to voicing their opposition to racism, sexism, and injustice, the National Colored Woman’s Congress called for unity and community and moral uplift. One local journalist wrote, “The colored women’s congress has a fixed purpose and that is to promote intelligence, refinement and morality in the negro home...By deliberation they mean to ascertain for themselves all that is before them for the proper uplift of their people.”[8]

They called for temperance, purity leagues, and mothers’ meetings to discuss the moral education of their sons and daughters. They sought the establishment of orphanages, reformatories, and other charitable institutions and encouraged the highest standards for their teachers, leaders, and parents.

In their final resolution, they challenged themselves by stating:

That we, the colored women of America, insist upon the highest degree of excellence as the standard of attainment for our race and pledge ourselves to do all in our power to help our artisan, business and professional men and women, who have shown themselves fitted for the respective pursuits in which they may be engaged.[9]

Though she boycotted the exposition, in part, because of the segregationist practices of its organizers, and, therefore did not attend the National Colored Woman’s Congress held there, radical Bostonian Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin covered it in her paper the Women’s Era. She published the resolutions in their entirety, though she disagreed with several of them. She felt, perhaps rightly, that the resolution aimed the “tone of the Negro press” specifically targeted her for her radical stances.[10]

Despite this, however, Ruffin wrote:

The Colored Woman’s Congress brought together a large number of progressive women and gave an additional impetus to the woman’s movement, beside opening up possibilities for the future...The Congress held by our women at Atlanta was a notable one, not only in its personal make-up, but also in the value of the work that was done — the subjects discussed, the papers read.

Image credit: New York Public Library

But Ruffin made sure to note that, “It was not, however, the first congress; that held in Boston last July enjoys that distinction.”

Nonetheless, she concluded that “Our women have caught the fever, and there is everything good to be hoped for in their efforts toward union and concentration.”[11]

Footnotes

[1] Atlanta History Center, "The 1895 Cotton States and International Expostition," The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition | Atlanta in 50 Objects | Exhibitions | Atlanta History Center; Theda Purdue, Race and the Atlanta Cottom States Exposition of 1895, (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 1.

[2] Purdue, 3; Atlanta History Center, "The 1895 Cotton States and International Expostition," The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition | Atlanta in 50 Objects | Exhibitions | Atlanta History Center.

[3] Purdue, 45, 47-48; “The Evolution of Woman,” The Freeman (Indianapolis), May 23, 1896, 2.

[4] Nathan Cardon, “The South's "New Negroes" and African American Visions of Progress at the Atlanta and Nashville International Expositions, 1895–1897,” The Journal of Southern History, May 2014, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp. 287-326, 322-333.

[5] Cardon, 322-333.

[6] Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow : women and the politics of white supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 26-27, Gender and Jim Crow : women and the politics of white supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920 : Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive, Accessed 10/1/2024; “The National Colored Woman’s Congress,” The Woman’s Era, January 1896, 2-5, Volume 2, Number 9 – The Woman's Era (emory.edu), Purdue, 47-48.

[7] “The National Colored Woman’s Congress,” The Woman’s Era, January 1896, 2-5.

[8] Cardon, 322.

[9] Mary E. Odem, Delinquent daughters : protecting and policing adolescent female sexuality in the United States, 1885-1920, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 28, Delinquent daughters : protecting and policing adolescent female sexuality in the United States, 1885-1920 : Odem, Mary E : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive, Accessed 10/1/2024, “The National Colored Woman’s Congress,” The Woman’s Era, January 1896, 2-5.

[10] Teresa Blue Holden, “Earnest Women Can Do Anything”: The Public Career of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, 1842-1904. A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Saint Louis University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 2005. 190-197.

[11] “The Negro Exhibit at Atlanta,” Women’s Era, January 1886, 12.