Last updated: February 27, 2025

Article

Women's Suffrage at Faneuil Hall

Boston Public Library, ca. 1850-1880.

To speak to-night in Faneuil Hall with the pictures of Sam Adams and those other great men of the Revolution around us, and to go back to the historical event which this Tea Party celebrates, brings to mind immediately the watchword of that hour 'Taxation without representation is tyranny.'[1]

- Mary Livermore

Suffragists occupied the Great Hall of Faneuil Hall, known as the 'Cradle of Liberty,' many times during their fight for political rights. Perhaps no other building in Boston served a more symbolic role in the Boston suffrage movement, as supporters echoed similar calls for liberty and equality as their forefathers had during the American Revolution. Women and men took to the stage of this storied hall numerous times throughout the suffrage movement, in some cases voicing opposition to the movement, but more often expressing support for increased political and social rights for women.

One of the earliest documented uses of Faneuil Hall by suffragists occurred in 1873. On December 15, the New England Woman Suffrage Association hosted the Woman's Tea Party in Faneuil Hall to commemorate the centennial of the Boston Tea Party. Thousands filled the Great Hall to hear the words of such abolitionists and suffragists as Lucy Stone, Frederick Douglass, and Mary Livermore. In their speeches, they referenced the ideals expressed during the nation’s founding in advocating for expanding women’s rights.[2]

Over the following years, suffragists used Faneuil Hall frequently for special events, celebrations, and festivals. Local and national leaders continued to take to the stage to speak for women’s suffrage, including Julia Ward Howe, Carrie Chapman Catt, Alice Stone Blackwell, and others. Faneuil Hall even served as the birth site of a new women’s political party – the Woman Suffrage Party of Massachusetts. In March 1912, suffragists representing the 26 wards of Boston and surrounding neighborhoods approved the platform of this new party. The platform focused of winning women the right to vote:

We declare that [women's] protection, safety, prosperity and happiness demand the extension to them of the right of suffrage, to the end that they have an equal voice in making and enforcing the laws which control their lives and happiness.[3]

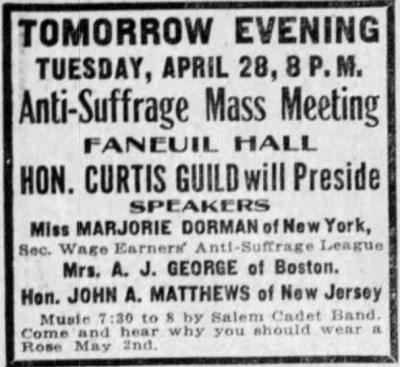

Boston Globe, April 27, 1914.

While suffragists used Faneuil Hall to rally support for their cause, so did anti-suffragists. The Boston Herald described a meeting held April 28, 1914 as "the biggest meeting of the anti-suffragists ever held in Boston."[4] Due the immense crowds, the meeting extended into two over-flow rooms in the building. Notable men and women anti-suffragists from New York and Massachusetts argued that suffragists had yet to convince the public of the benefits of granting suffrage to women, a population who they claimed did not want the vote. Local anti-suffrage leader Mrs. A. J. George remarked, "it would be a brutal view of [women’s] 'rights' to insist that the mother of her race shall forfeit her rights and exemptions before the law and in civil life, and enter into competition with man."[5]

In the months leading to the 1915 election, in which Massachusetts had a state referendum on women's suffrage, Faneuil Hall became an even more contested space. Both sides continued to hold meetings and rallies, and a debate between Massachusetts suffragist Edna Spencer and New York anti-suffragist Marjorie Dorman occurred. Suffragists and anti-suffragists sat on opposing sides of the hall and they cheered for their representative.[6]

Hoping for victory with the suffrage referendum, Massachusetts suffragists planned a victory celebration in Faneuil Hall days after the 1915 election. When the hope of victory turned into the reality of defeat, suffragists instead held a gathering to recommit themselves to the suffrage cause and support the new federal amendment that would grant women the right to vote. The Boston Journal noted of the event: "The suffragists were so beaming with courage and smiles and confidence that there was no doubting their sincerity."[7]

In 1920, suffragists finally obtained their victory with the ratification of the 19th Amendment. They once again turned to the 'Cradle of Liberty'as the chosen location to recognize this achievement. After marching through the streets with a victory parade, suffragists held a celebration at Faneuil Hall. A rousing crowd of over 1,500 people packed into the Great Hall to hear Massachusetts suffrage leaders speak. They remembered the suffragists who had worked for progress before them while they also looked to the possibilities that came with voting. Having realized her mother's vision made in the same hall nearly 50 years prior, Alice Stone Blackwell remarked:

Now that we have the vote, what are we going to do with it? Let us remember that the ballot is neither a plaything nor an ornament, but a tool and a weapon. It is a tool which, rightly used, can do almost anything.[8]

Footnotes

[1] Mary Livermore speech, as printed in “New England Woman’s Tea Party,” The Woman’s Journal 4, no. 51 (December 20, 1873).

[2] "New England Woman's Tea Party," The Woman's Journal 4, no. 51 (December 20, 1873): 1, 4, 5, 8. For more information, please visit the NPS article: New England Woman’s Tea Party.

[3] Blackwell Family, “Woman Suffrage Party of Massachusetts,” Papers of the Blackwell family, 1831-1981, Folder 569, Other printed suffrage and anti-suffrage, 1894-1915, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, http://schlesinger.radcliffe.harvard.edu/onlinecollections/blackwell/item/48789720/88; “Deny Aid to Elect Men,” The Boston Globe, March 6, 1912.

[4] "'Antis' Attack Suffrage in Faneuil Hall," The Boston Herald, April 29, 1914.

[5] “Anti Suffragists Turn Out in Force,” The Boston Globe, April 29, 1914.

[6] “Debate in Faneuil Hall,” The Boston Globe, October 27, 1915.

[7] “Suffragists Undismayed Hold Rally Faneuil Hall Rings with Enthusiasm,” Boston Journal, Nov 05, 1915.

[8] "Bay State Suffragists Have Victory Parade," The Boston Globe, September 23, 1920; “When Boston Marched,” The Woman Citizen 5 (October 2, 1920); "Will March in Role of Ratifying States," The Boston Globe, September 18, 1920.