Last updated: October 1, 2020

Article

Val-Kill Industries

NPS Photo

By 1926, when Eleanor Roosevelt and three friends—Nancy Cook, Marion Dickerman, and Caroline O’Day—joined in partnership to establish Val-Kill Industries, the American Arts and Crafts Movement had reached its declining years.1 Some advocates, disheartened by the movement’s inherent inability to effect change in an industrial society, redirected their momentum, drawing national attention to the craft traditions of America’s colonial past.2 The decade of the 1920s witnessed an explosion of activity in what historians refer to as the Colonial Revival, a complex reactionary movement against growing immigration, multiculturalism, and anxieties over urbanism and modernism.3

Val-Kill Industries embraced both Arts and Crafts and Colonial Revival ideologies. These movements had much in common, sharing an appreciation for simplicity and honesty in design and materials, nostalgia for a pre-industrial past, and emphasis on agrarian values.

Over the course of its 10-year life, Eleanor Roosevelt would see Val-Kill Industries in a broader context. In the process, she played a key role in shepherding Arts and Crafts ideas and ideals into larger government-sponsored initiatives that adopted many of the movement’s philosophical attitudes toward craft, labor and human dignity. In this way, Val-Kill Industries and Eleanor Roosevelt achieved some success where the Arts and Crafts movement had fallen short. When Franklin D. Roosevelt became President, Val-Kill Industries was a model for some New Deal economic recovery programs.

Mrs. Roosevelt met Nancy Cook and her companion Marion Dickerman in 1922 at a fundraising luncheon sponsored by the Women’s Division of the New York State Democratic Committee. Shortly after, Mrs. Roosevelt invited them both to spend a weekend at Hyde Park. A vibrant friendship followed and eventually, with the encouragement of FDR, the three women built a cottage on the Roosevelt family estate in Hyde Park, New York. Val-Kill Cottage was completed in 1926 and became the symbol for a partnership that included Mrs. Roosevelt, Cook, Dickerman and Caroline O’Day. Joined by their mutual dedication to social reform and progressive politics, together they published the Women’s Democratic News, purchased the Todhunter School in New York City, and established the Val-Kill Furniture Shop.4

Nancy Cook was the driving spirit behind Val-Kill Industries, suggesting that the workshop at Val-Kill make reproduction early American furniture.5 Cook attended Syracuse University from 1909 to 1912, and while there, was likely a student of Irene Sargent, close associate of Gustav Stickley and editor of his publication The Craftsman from 1901 to 1905.6 Under Sargent’s influence, Cook may have developed her life-long interest in craft and early American furniture.7

Making furniture was something that Nancy Cook had always wanted to do. But Mrs. Roosevelt’s decision in 1926 to establish Val-Kill Industries was prompted by a growing national crisis, and a desire she shared with FDR to do something locally in response. The outbreak of the World War in 1914, which severely disrupted agricultural production in Europe, presented American farmers with an opportunity to supply the European food market. During that time, agricultural production in the Unites States increased on an unprecedented scale as America’s farmers overextended themselves to meet market demand and profit as never before. This all came to an abrupt halt with the restoration of peace and European farming resumed. American farmers were plagued by massive surpluses and rapidly depreciating prices. Compounded by overwhelming debt incurred to meet market demand and escalating foreclosures, the United States plummeted into an agricultural depression that persisted throughout the 1920s. Unemployed farmers and their families began to leave the countryside in search of employment opportunities in urban areas at such an alarming rate that the farm crisis became the most urgent national political issue.8

Agriculture remained the dominant economic activity in Dutchess County, New York during the first quarter of the twentieth century. The county’s most important agricultural products were dairy, apples, corn and barley. Increasing competition and the invention of refrigerated rail cars weakened the region’s position as a leading supplier of the vast, nearby New York City market. This market shift and the concurrent agricultural depression took its toll. The number of acres actively farmed in New York dropped from 23 million at its peak in 1880 to 18 million by 1930—an average loss of 40,000 acres per year. As was happening across the nation, abandoned farmland was becoming all too common in Dutchess County.9

Mrs. Roosevelt, responsible for promoting sales, never missed an opportunity to explain the purpose behind Val-Kill Industries:

For some years I had been rather intimately acquainted with the back rural districts of our state, and realized very clearly the problems of country life. If it were possible to build up in a rural community a small industry which would employ and teach a trade to the men and younger boys, and give them adequate pay, while not taking them completely from the farm, I felt that it would keep many of the more ambitious members in the district, who would otherwise be drawn to the cities. It was with this in mind that we decided to make furniture our test case.10

Social reformers had long thought craft and agriculture ideal companions because handicrafts could provide profitable work to supplement the farmer’s income. Many attempts were made toward this end, but they were not widespread and seldom met expectations.11 As many of its predecessors had tried, Val-Kill was intended to be a vocational program to serve the needs of local farming families. “Eventually,” Mrs. Roosevelt told one reporter in 1929, “we plan to have a school for craftsmen at Val-Kill, where the young boys and girls of the neighborhood can learn cabinetmaking or weaving, and where they can find employment, rather than have to go down to the city to work.”12 Despite Mrs. Roosevelt’s continued insistence on this point in her promotion, Val-Kill never realized this aim.13

Sometime in 1926, Mrs. Roosevelt approached Charles Cornelius for advice on her plans to establish the Val-Kill Shop. Cornelius, the first curator of American furniture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, offered access to the museum’s collection and introduced the ladies to Morris Schwartz, a prominent Hartford, Connecticut furniture restorer and leading authority on American furniture. Schwartz was restoring many of the pieces destined for exhibit at the Metropolitan and advised the women on American furniture and aspects of design. In the years that followed, Schwartz maintained contact with them, supplying some furniture for Val-Kill Cottage, and later, his son George would work at Val-Kill in the finishing room and delivering furniture orders.

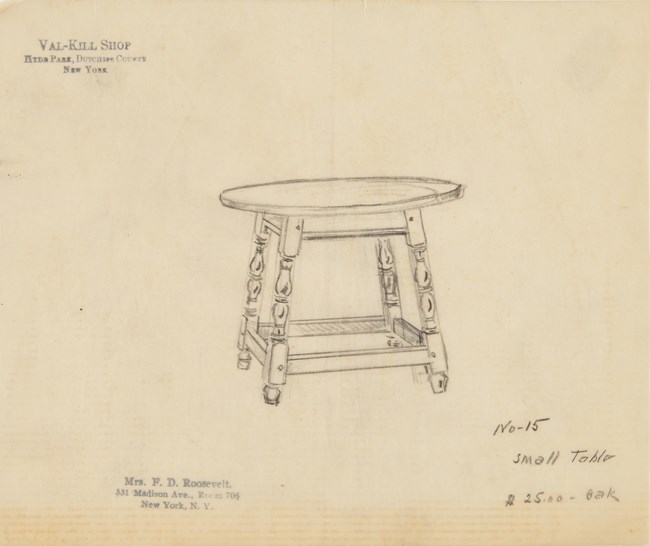

During this time Cook dedicated herself to the study of historic furniture styles, researched recipes for stains and the finishing process, and drafted sketches of furniture based on antiques in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the large collection assembled by Wallace Nutting and recently sold for exhibit at the Hartford Memorial (later renamed the Wadsworth Athenaeum). The shop employed a part-time draftsman to convert Cook’s sketches into measured drawings from which blueprints and templates were made. Henry Toombs, architect for Val-Kill Cottage, drafted the shop drawings in that first year. He was succeeded by Lewis Macomber, and architect working in New York City. Toombs and Macomber also submitted some of their own designs for Cook’s consideration.14

With construction of the cottage and factory nearing completion in the winter of 1926, Mrs. Roosevelt and Cook hired Frank Landolfa, an Italian immigrant who arrived in New York City on Christmas Day in 1925. Trained in a family of cabinetmakers and woodworkers, Landolfa possessed what Mrs. Roosevelt described as an “artist’s love of fine workmanship.”15 Landolfa came alone to the United States to establish a branch of an import-export business for his family. His efforts were unsuccessful, obliging him to fall back on what he knew—woodcraft. Landolfa found work with a New York City furniture maker.16 At night, he instructed boys in a vocational program at Greenwich House, where Mrs. Roosevelt served as a trustee.

Greenwich House is a thriving community center today founded during the Settlement Movement in 1902 to improve the lives of the predominantly immigrant population living in what was then Manhattan’s most congested neighborhood. By 1926, Greenwich House was developing pioneering vocational education programs in the arts and craftsmanship. Mrs. Roosevelt approached Nicola Famiglietti, an immigrant master cabinetmaker from Naples who ran the woodcarving workshop, for assistance in locating a craftsman for Val-Kill. Famiglietti recommended Landolfa who agreed to an interview with Miss Cook (with the aid of an interpreter) and arrived at Val-Kill in December of 1926 to set up the Val-Kill workshop.17

Val-Kill Cottage was nearing completion and the furniture factory was still under construction when Landolfa arrived. Shortly after, Cook purchased machinery and workbenches selected by Landolfa from a New York City supplier.18 Landolfa began constructing furniture for Val-Kill Cottage during the first months of 1927.19

The Val-Kill Shop was soon bustling with several important orders placed that winter. FDR was the first customer, purchasing furniture for his newly renovated cottage at Warm Springs, Georgia. Roosevelt family friend Henry Morgenthau Jr. (and later FDR’s U.S. Secretary of the Treasury) placed a large order for his country home in upstate New York. FDR’s mother placed an order of tables for the James Roosevelt Memorial Library she built for the town of Hyde Park.

A sampling of products had to be made in time for the first exhibition and sale scheduled for May at the Roosevelts’ East 65th Street townhouse in New York City. To meet the deadline, Landolfa hired two additional cabinetmakers and two finishers, all of them Italian immigrants. The sale included a copy of a large walnut gate-leg table in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a desk-on-frame, a pair of leather upholstered Cromwellian-style chairs, an assortment of butterfly drop-leaf tables, trestle tables, mirrors, a dressing table, and chairs. Guests could also view photographs and drawings illustrating the full range of Val-Kill Shop products. The exhibition and sale was a success—the shop received more orders than it could sustain necessitating the need for a fourth craftsman hired the following month.

Otto Berge arrived at Long Island City from Norway in 1913. Berge was a wheelwright by training, and was largely self-taught as a cabinetmaker following his arrival in the United States. After working a short time as a woodcrafter in an automobile body factory and then a few years as a house carpenter, Berge took a job repairing furniture at the East 13th Street Antique Shop in New York City. His employer was a dealer associated with Alfred G. Compton.20 Berge developed his craft by instinct and studied the furniture collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He was also acquainted with Wallace Nutting and Morris Schwartz. “You have to study your art,” Berge said, “and in order to study any kind of art you have to go way, way back and you have to study and you have to find out who knew more than yourself.”21

Schwartz, who had earlier advised Mrs. Roosevelt and Miss Cook, referred Berge to the Val-Kill Shop. Berge interviewed with Nancy Cook in New York City and joined the Val-Kill Shop in the summer of 1927. The shop was busy and well equipped when he arrived, but he was critical. Berge thought the designs by Toombs and Macomber were attractive, but lacking correctness, pointing out their unfamiliarity with authentic American style and techniques. Berge’s criticism was directed, in part, toward adaptations made in the designs to make them “suitable for modern needs,” a feature Mrs. Roosevelt promoted in magazine articles, interviews, and radio spots.22

According to Berge, the shop was joining furniture with glue and dowels when he arrived and credits himself with introducing eighteenth-century construction methods, including dovetail and mortise-and-tenon joints. This isn’t consistent however with furniture known to be among the early pieces Landolfa crafted for Val-Kill Cottage.23 Berge was a purist, confident in his craft, eager to be correct. He certainly may have witnessed methods that did not meet his approval, and given his exposure to the American antique market and museum collections, he may have refined or perfected practices at Val-Kill.

The real issue may have been the pressure the shop was under in that first year to complete orders and be ready for the first exhibition and sale. Mrs. Roosevelt recalled “how difficult it was at first to instill into the minds of the workmen that what was expected of them was craftsmanship, not speed.”

Even though we selected our workmen for their artistic leanings as well as their technical ability…they could not understand, at first, that we did not want the furniture slapped together any old way in order to get it finished. They were so used to rushing through with a job, using the methods of joining and finishing which would give quick though not always lasting results, that it seemed incredible that anything else could be asked of them in this age of factory production. But once they realized that what we wanted was the very best cabinet making of which they were capable, they swung into the spirit of the undertaking, and now they take a genuine pride in turning out a beautiful piece of work.24

Whatever the case, it was about the time of Berge’s arrival that the Val-Kill Shop adopted a marketing strategy that highlighted construction methods. In an early article Caroline O’Day made reference to “the careful fitting of part to part with mortise and tenon joints pinned with wooden pegs. The common and usual way of putting furniture together in these hurried days is with dowels and glue, none of which have any part in the construction of Val-Kill furniture.”25

Val-Kill designs offered simplicity that championed traditional values. Rather than develop a full range of American antique styles like many competitors, shop practices at Val-Kill were motivated by economy to keep production costs modest.26 The more ornate features typical of the Queen Anne style or the characteristic inlay of Federal furniture would have added substantially to production costs. As noted in a 1931 New York Times article, “All of the furniture emphasizes directness of construction and simplicity of ornamentation. Most of the pieces are reproductions of that great age of simply carved and turned wood-work, the Jacobean era of the seventeenth century.”27

Cook assigned each order for a piece of furniture to one craftsman who would be solely responsible for selecting the wood, preparing the layouts, making the cuts, and assembly until it was ready for the finishing room.28 Lumber supplies were purchased from Ichabod T. Williams & Sons in New York City, the oldest and largest firm in the world dealing in mahogany and other imported hardwoods.29 The men would drive to New York City and select the wood themselves. The machines were shared by the men, but each was assigned his own workbench and, as was customary, a craftsman was responsible for his own hand tools, a set typically including chisels of various types and sizes, planes, handsaw, and a dovetail saw. Prior to delivery, a finished piece of furniture would receive the Val-Kill Shop trademark.30

Finishing was a meticulous process. Repeated sanding, staining, and polishing produced a silken luster. During the first months, Cook worked in the finishing room herself, assisted by two young men from the local area. As orders increased, Landolfa recruited Matthew Famiglietti, an acquaintance from Greenwich House. Famiglietti was hired to manage the finishing room and train the steady procession of local boys employed for that purpose. Mrs. Roosevelt boasted that although the furniture was made by expert craftsmen, “we also employ boys of the neighborhood, and teach them the trade of finishing furniture, in the best possible way.”31 Famiglietti arrived late in the year 1927 and remained until Val-Kill Industries finally closed in 1936.

Caroline O’Day described the appearance of the finishing room and the process:

The unstained piece is taken to the finishing room. Huge glass jars filled with mysterious liquids are on the shelves that line the walls. Jars and bottles of gruesome looking mixtures stand in corners and under workbenches. Indeed the place might be mistaken for the workshop of an alchemist of old were it not for the collection of chairs and tables, chest of drawers, bed and benches piled high, awaiting their turn to be stained. This staining process seems almost a ritual, so carefully, almost reverently, is it done—a little color at first, carefully rubbed down, then a second or third coat, but always preserving the beauty of the grain of the wood. The furniture gradually takes on the desired richness of tone. When this is finally satisfactory, the polishing begins. It is done entirely by hand, for hours and hours, until the wood becomes like velvet to the touch.32

Cook developed a document for charting as many as fifteen steps in the finishing process. Clifford Smith, caretaker and gardener at Val-Kill who worked in the finishing room specifically recalled using a water stain, lacquer, wet sandpaper, pumice and burlap in the finishing process.33

Cook was a stern taskmaster and had a tendency toward micromanagement, requiring the employees to complete detailed timesheets. According to Landolfa, she developed a timetable estimating the amount of time needed to complete each piece of furniture.34 Her notations giving specific instruction on how to perform a particular task appear frequently on Val-Kill shop drawings—“Be sure to get the wood marked K.D. for the top. Don’t make a mistake,” or “Pick out very nice wood and do nicely. Time on last ones 12 ¾ hrs” are typical of her annotations.35

The business grew steadily, reaching its peak in 1930, surviving the Wall Street market crash of 1929. During the period of growth, the Val-Kill Shop employed as many as six cabinetmakers, crowding the workmen and forcing an expansion of the factory. Two additions were constructed in 1928 and a large addition in 1929, nearly doubling the shop’s total size.

Encouraged by strong sales, Mrs. Roosevelt and Miss Cook considered developing a forge at Val-Kill. The Val-Kill Shop’s steady decline began in 1931 as the Great Depression took its toll. The economy and resulting drop in furniture sales delayed their plans until 1934, and Mrs. Roosevelt showcased the first pewter wares from the Val-Kill Forge at the April 1935 exhibition and sale held at her New York City residence.

The Forge was run by Otto Berge’s younger brother Arnold, who immigrated to the United States in 1927 and held various jobs in New York City before moving to Hyde Park. Arnold was first apprenticed to Otto in the furniture shop in 1929. A quick study, he made several fine pieces of furniture under his brother’s instruction. Arnold consented to operate the Val-Kill Forge and received his training in only a few weeks from a New Jersey pewtersmith.36 The Forge offered more than fifty items, including plates, bowls, porringers, mugs, candlesticks, pitchers, and lamps, most copies of popular eighteenth-century forms and a few modern products such as match book covers and cigarette boxes.37 Berge usually worked with one assistant, Clifford Smith from 1935 to 1937, followed by Frank Swift.

Berge continued operating the Forge for Mrs. Roosevelt and her partners on the Val-Kill property after the Furniture Shop was disbursed. In 1938, Berge relocated the operation of the Forge as sole proprietor from 1938 until the war when it became difficult to obtain the necessary raw materials. Berge closed the Forge and went to work in a shipyard, and did not reopen when the war ended.

In 1934 Mrs. Roosevelt visited the hand-weaving room at Biltmore Industries in Asheville, NC with the determination to establish a similar model at Val-Kill. Upon her return to Hyde Park, she learned that her housekeeper, Nelly Johannesen, had an interest in weaving. Fred Seeley, who had purchased Biltmore Industries from its founder and patron Mrs. George W. Vanderbilt, gave Mrs. Roosevelt a loom and offered to train a weaver from Val-Kill.38

Nelly Johannesen worked as housekeeper at Val-Kill from 1928 to 1930 when her son Karl was employed in the Furniture Shop. In 1933, Johannesen built a Tea Room and gas station at the entrance to Val-Kill with encouragement from Mrs. Roosevelt. In 1934, Johannesen spent eleven days studying weaving at Biltmore, and returned again in 1935 for more training. Working primarily during the winter months, Nelly Johannesen wove an average of 800 yards of homespun cloth in a year and sold it for $3.00 per yard. “Most of Mrs. Johannesen’s material is used for dresses, coats and suits,” a local paper reported, “Varicolored bolts are stacked in the new south room, built on to the teashop recently by her son. There are solid colors and stripes, subdued shades and bright red-and-green plaids.”39

The weaving industry was intended to be part of Val-Kill Industries, but Johannesen managed the business quite independently. Over a short period of time, she was able to repay Mrs. Roosevelt for her investment in the set-up costs. By 1936, she was managing the accounting herself as sole proprietor.

By the end of 1930, orders for the Furniture Shop dropped so low that most of the workers were let go, leaving only Landolfa, Famiglietti, and Otto Berge. During the remaining years, orders were scarce and infrequent, preventing steady full-time work. In 1932, Landolfa, with more time on his hands, began making small wood accessories—bookends, salad bowl sets, jewelry boxes, letterboxes, cheese plates, paper knives, and picture frames. Some of these were made with lumber Mrs. Roosevelt salvaged from the White House, removed during 1927 renovations to the roof.40 Items manufactured from this stock were affixed with a small, engraved brass plate indicating the wood’s origin.

The hardest years for the Furniture Shop were 1934 and 1935, when Landolfa finally left for more reliable income. Mrs. Roosevelt arranged a job for him restoring furniture for an acquaintance. He eventually opened his own shop in Poughkeepsie and continued making and restoring furniture for another forty years until his retirement.

Finally, Mrs. Roosevelt and her partners began liquidation of the Furniture Shop. Mrs. Roosevelt began making plans to convert the factory building into her own residence. Otto Berge stayed through 1936 to complete the final orders, most of them placed by Mrs. Roosevelt for her new cottage. Berge had been setting up a shop at his home, presumably to start his own business as soon as he was able. He accepted the women’s offer to take what machinery from the shop he still needed and the Val-Kill Shop trademark. Berge continued making furniture under the Val-Kill name until his retirement in the 1970s.

Events leading to the decision to dissolve the Val-Kill partnership are not precisely known. A personal disagreement between Mrs. Roosevelt and Miss Cook in 1938 was the highlight of what may have been a growing disaffection. But economic realities were really to blame. Managing the shop during a recession coupled with her political responsibilities at the State Democratic Party headquarters were having an effect on Nancy Cook’s health.41 A note Mrs. Roosevelt dashed off to her friend Lorena Hickok confirms the circumstances:

Lots of work going on today but moving the shop out and giving the furniture to Otto and machinery and the other two boys the pewter and little things is really a great relief to [Nancy] and will mean a more peaceful life.42

The assessment of Val-Kill’s financial health has never been fully understood. Nancy Cook apparently destroyed most of the records shortly before her death.43 Family members and friends close to Mrs. Roosevelt later expressed concern that she was underwriting the shop’s losses. In his published memoir, Mrs. Roosevelt’s son Elliott disparagingly referred to his mother’s “hopeless task of turning Val-Kill Industries into a paying concern.”44 Mrs. Roosevelt even admitted “I put up most of the capital from my earnings from radio and writing and even used some of the small capital that I had inherited from my mother and father.”45 Mrs. Roosevelt’s secretary, Malvina Thompson, added that Val-Kill failed for lack of expertise in business management and that Cook refused to bring in help.46 Otto Berge agreed.

But the scant surviving financial records suggest that the situation was not always so desperate. With the exception of the very difficult year of 1930 and the final years 1935 and 1936, records indicate that the Val-Kill Shop was making a modest annual profit divided equally among Roosevelt, Cook and Dickerman. Most years, they earned a profit that ranged from $500 to $1,900.47 However, the return on their total investment in Val-Kill Industries of $18,610 from 1925 to 1936 was only $5,028—a loss of $13,582.

But analysis of Val-Kill’s success based solely on the fiscal realities misses the point. Despite Val-Kill’s inability to sustain itself as a commercial venture, it did succeed in some ways where other cottage industries had failed. The experiment at Val-Kill paved the way for larger initiatives that became possible when Franklin D. Roosevelt took the oath of office in 1933. Among the New Deal agencies established by FDR’s administration, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) organized more than 3,000 craft projects, the Farm Security Administration (FSA) experimented with cottage industry, and many more government-sponsored programs embraced some form of traditional craft to liberate Americans from poverty and restore their dignity.

The relationship between Val-Kill Industries and the quest for solutions to the crises of the Depression were early observed by one writer who paid a visit to the Val-Kill Shop. “While therefore, Mrs. Roosevelt so vigorously and so effectively sponsors the handicraft movement, it is almost plain that she is not fully aware of the revolutionary bearing and implications of her sponsorship.” This perceptive reporter recognized Eleanor Roosevelt as the pivotal figure in transforming a national aesthetic movement into effective government programs. “The world is full of Val-Kill workshops,” he further remarked, “What is happening in America in the encouragement and development of handcrafts is significant more because of the political turn it has taken through Mrs. Roosevelt than because of any other aspect of the movement.”48

By Frank Futral, Curator, Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites

Notes

1 Val-Kill Industries was variously referred to as the Val-Kill Shop, Roosevelt Industries, and the Hyde Park Village Craftsmen.

2 See Robert W. Winter, “The Arts and Crafts as a Social Movement,” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, Vol. 34, No. 2 (1975): 36-40. Winter cites Mary Ware Dennet, a leader of the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts, whose writings concluded with a tone of resignation that radical reform could not occur without fundamental change in the economic system. Even at Val-Kill, craftsman Frank Landolfa admitted “we couldn’t compete with the factories.” See Frank S. Landolfa, interview by Emily Williams, Poughkeepsie, NY, 14 July 1978, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

3 See Alan Axelrod, ed, The Colonial Revival in America (New York: W.W. Norton, 1985).

4 Eleanor Roosevelt was editor of The Women’s Democratic News, Marion Dickerman served as vice-principal of the Todhunter School, and Nancy Cook managed the Val-Kill Furniture Shop. Beyond contributing her share of the financial support and authoring a few articles, Caroline O’Day’s role in the partnership is unclear.

5 Mrs. Roosevelt stated in a letter to Marion Dickerman that she supported Val-Kill Industries “because I felt that Nan was fulfilling something which she had long wanted to do.” See Eleanor Roosevelt to Marion Dickerman, 9 November 1938, President’s Secretary’s File, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library. In published articles and interviews, Mrs. Roosevelt frequently credited Cook’s primary role in creating and managing the Val-Kill Shop.

6 In a given four-year cycle, a student could expect to take several of Sargent’s classes covering aesthetics, architectural history or the history of fine arts. She defined art broadly to include all forms of craft, giving equal attention to Rookwood Pottery as to the Renaissance.

7 After graduating from Teaches’ College at Syracuse, Cook taught art and handicrafts to high school students in Fulton, New York.

8 David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999): 16-18.

9 See Edith Van Wagner, ed., Agricultural Manual of New York State (Albany: State of New York Department of Farms and Markets, Division of Agriculture, 1918): 65; and Martha Collins Bayne, County at Large: A Norrie Fellowship Report (Poughkeepsie: The Women’s City and County Club with Vassar College, 1937): 53.

10 See Eleanor Roosevelt, “Making a Town Furniture-Minded,” The Spur (15 December 1931): 28; and “Mrs. Roosevelt’s Story of Val-Kill Furniture,” Delineator (November 1933): 23.

11 Coy L. Ludwig, The Arts & Crafts Movement in New York State, 1890s-1920s (Hamilton, NY: Gallery Association of New York State, 1983): 16.

12 Frieda Wyandt, “A Governor’s Wife at Work," Your Home (September 1929): 68.

13 Frank Landolfa admitted in an interview, “I was supposed to teach young local men, which I never did because nobody ever came.” Otto Berge remembered teaching woodworking classes at night and on Saturdays after he arrived, but said the classes didn’t last because of rivalry among the local boys. Most young men employed at Val-Kill were put to work in the finishing room. See Landolfa, 14 July 1978 interview; Frank Landolfa, Interview by Emily L. Wright, 25 July 1978, Poughkeepsie, NY, Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site; and Otto Berge, Interview by Emily L. Wright, 17 July 1978, Red Hook, NY, Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site.

14 Henry Toombs was a cousin of Caroline O’Day. After studying architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, Toombs trained in the offices of Paul Cret and McKim, Mead and White. Very little is known of Lewis Macomber. He maintained an office at 665 Fifth Ave. in New York City.

15 Eleanor Roosevelt, typescript for article dated 1927, Eleanor Roosevelt Papers, Box 3022, Folder: “Val-Kill Industries,” Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

16 In his interviews, Landolfa identifies the shop variously transcribed as John Soma, John Somnia, or John Sonmma.

17 Landolfa interview, July 25, 1978. See also “Parts of House Work of Boys of Greenwich House Workshops,” The Westfield Leader (October 12, 1932): 2; and “Greenwich Woodcarvers,” Time (December 3, 1928).

18 Shop machinery included a table saw, band saw, jointer, shaper, hollow chisel mortiser, and woodturning lathe. See Otto Berge, interview by Emily L. Wright, 31 July 1978, Red Hook, NY, Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site.

19 For a while, Val-Kill Cottage also served as “the demonstration house for the furniture itself.” See Wyandt, 69.

20 Alfred Compton (1835-1913) was a professor of physics and mechanics at the College of the City of New York. He authored several books on manual training and the craft of woodworking, among them Manual Training: First Lessons in Wood Working (1888), First Lessons in Metal-Working (1890), and Advanced Metal-Work (1898). See “Prof. A.G. Compton Dies,” The New York Times (December 13, 1913).

21 Otto Berge, interview by Dr. Thomas F. Soapes, 19 September 1977, Red Hook, NY, Eleanor Roosevelt Oral History Project, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

22 Wyandt, 69. Notices for the bi-annual exhibitions and sales published in the New York Times also make reference to these adaptations.

23 Shop drawings dated before Berge’s arrival clearly illustrate mortise and tenon construction details.

24 Wyandt, 68.

25 Mrs. Daniel O’Day, “Bringing Back Artistic Furniture of the 17th Century,” Motordom (March 1929): 9.

26 Several sketches are annotated “too expensive.”

27 Walter Rendell Storey, “Village Craftsmen Show Their Talent,” New York Times (January 11, 1931).

28 The process is outlined in several feature articles on Val-Kill: “Once the drawing is presented to the chosen craftsman, the responsibility of handling every operation is his. From selecting the most suitable pieces of kiln-dried wood in the cellar of the shop to polishing down the last coat of wax or varnish, the piece never leaves his hands. There are no specialists for each operation, for mass production has never infected Val-Kill.” See “A Governor’s Wife and Her Workshop,” The Home Craftsman (July/August 1932): 90. On the point of finishing, the editors of The Home Craftsman were incorrect, but the idea of the single craftsman overseeing all aspects of the production was a point to be made in contrast to the monotony of the factory system, isolating workers required to turn out just one part over and over. Otto Berge also emphasized that each craftsman was wholly responsible for the manufacture of a single piece of furniture, with exception of the finishing process.

29 Lumber receipts are in the Otto Berge Papers, Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites. On the history and reputation of Ichabod T. Williams & Sons, see John C. Callahan, “The Mahogany Empire of Ichabod T. Williams & Sons, 1838-1973, Journal of Forest History, Vol. 29, No. 3 (July 1985): 120-130.

30 Two trademarks were in use at Val-Kill. The first was a simple block print with the word VAL-KILL. According to Landolfa, the second trademark came into use in 1933, also a block print with the word VALKILL framed within a double rectangle. Both trademarks appear on surviving Val-Kill furniture. One of these may appear in combination with the craftsman’s signature (a block print of his first name) and a catalog number. Trademarking was not consistently practiced.

31 Eleanor Roosevelt to Mr. D.D. Streeter, 12 May 1930, Eleanor Roosevelt Papers, Box 15, Correspondence S-Miscellaneous, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library. See also typed manuscript, Eleanor Roosevelt Papers, Box 3022, Val-Kill Industries, 1927, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

32 O’Day, 9.

33 Clifford Smith, interview by Emily L. Wright, 26 July 1978, Hyde Park, NY, Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site.

34 Johanne Berge, wife of Val-Kill Industries employee Arnold Berge, said that the time sheets were necessary in the finishing room because the young boys didn’t apply themselves and played too much. See Johanne Berge, interview by Emily L. Wright, 1 September 1978, Saratoga Springs, Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Sites.

35 See Val-Kill Shop Drawings Collection, National Park Service, Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site. Notations are from drawings 01.004.03 and 01.034.06.

36 The pewtersmith is identified in the interviews as a man named Eichner (probably Jacob Eichner). Johanne Berge, interview.

37 Arnold made several attempts to manufacture iron hardware and experimented with approximately 20 samples that include boot scrapes, strap hinges, latches, and locks. Finding iron too difficult to work with, the production of hardware was abandoned. Had economic circumstances been different, the Forge would have expanded to include other metals.

38 Biltmore Industries was established in 1901 by Mr. and Mrs. George W. Vanderbilt to train local young men and women in handcraft production. At Biltmore, they produced furniture and were famous for their woolen homespun cloth. President Roosevelt was particularly fond of their lightweight white wool cloth.

39 “Violet Avenue Woman Weaves,” Hudson Valley Sunday Courier, n.d. Quoted in Emily L. Wright, “Eleanor Roosevelt and Val-Kill Industries,” (unpublished report for Eleanor Roosevelt’s Val-Kill, Inc., October 1978): 55.

40 President Calvin Coolidge replaced the White House’s leaky roof in 1927 and at that time added a third floor.

41 Despite speculations, Marion Dickerman insisted that Val-Kill “ceased operations only because the volume of orders and work were becoming injurious to Miss Cook’s health.” Quoted in James R. Kearney, Anna Eleanor Roosevelt: The Evolution of a Reformer (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1968): 169. Joseph Lash quotes Dickerman as saying “The load that Nan carried nearly killed her.” See Joseph P. Lash, Eleanor and Franklin (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1971): 476.

42 Roosevelt to Lorena Hickok, 11 May 1936, Lorena Hickok Papers, Box 3, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

43 Author James R. Kearney stated that a confidential source told him that Cook destroyed the financial statements. See Kearney, 169.

44 Elliott Roosevelt and James Brough, A Rendezvous With Destiny: The White House Years (G.P. Putnum’s Sons, 1975): 159.

45 Eleanor Roosevelt, This I Remember (New York: Harper and Brothers): 34.

46 Lash, 476-7.

47 Profit was $562 in 1928; $1,900 in 1929; $880 in 1931; $1,000 in 1932; and $686 in 1934. Regardless of what Cook, Dickerman, and Roosevelt each invested, they shared the profits equally. See “Construction of the Shop Building and with the Additions,” Cook-Dickerman Papers, Box 12, Folder 6, Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site.

48 Sydney Greenbie, “Whither, Mrs. Roosevelt? A Refuge from Speed and Monotony—Val-Kill,” Leisure (May 1934): 8.