Last updated: February 26, 2024

Article

United States Coast Guard Women's Reserve (SPARS)

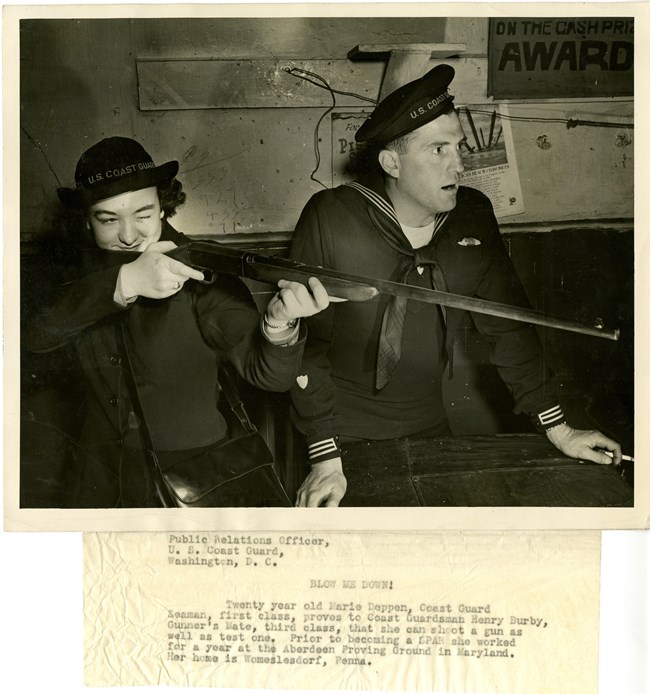

...for a year at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. Her home is Womeslesdorf, Penna.”

Courtesy United States Coast Guard Historian's Office. Public domain. 230505-G-G0000-117.JPG.

Congress created the United States Coast Guard Women’s Reserve during World War II. It was more commonly known as the SPARS, an acronym for the Coast Guard motto “Semper Paratus—Always Ready.” With men increasingly needed on sea duty, the Coast Guard had to fill crucial roles at its stations on the home front.

After several weeks of training, Spars took on jobs as officers, seamen, clerical workers, logistics specialists, photographers, parachute riggers, air traffic controllers, and radio operators.[1] They could earn the same pay and do many of the same jobs as Coast Guard men. Like their counterparts in other branches of the military, the 10,000 women who served as Spars benefited from new opportunities and faced new challenges and obstacles as they broke barriers for women in the United States military.

Establishing the SPARS

After the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the Coast Guard found itself with a shortage of personnel. Male Guardsmen were being called to sea duty, leaving essential shore jobs unfilled. To solve the problem, Congress passed a bill creating the first women’s division of the Coast Guard. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed it into law on November 23, 1942. Dorothy C. Stratton, a lieutenant in the Navy Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service (WAVES), became director of the new unit.

Art by Robert E. Lee. Courtesy United States Coast Guard Historian’s Office, photo by Tim Mills. Public domain. 230712-G-G0000-101.JPG

Recruitment

The SPARS permitted women to enlist and become commissioned officers for the duration of the war plus six months. Between 1942 and 1946, more than 10,000 women volunteered. Spars had to be American citizens ages 20-36. They could be married, but not to a man in the Coast Guard--probably to discourage couples from enlisting in order to avoid separation. Spars also could not have children younger than 18. Recruits had to pass aptitude tests and a physical exam.

The average enlisted Spar was a 24-year-old single high school graduate who had been working in a clerical or sales job. The average officer candidate was 29, single, had a college diploma, and had been employed as a teacher or civil servant before becoming a Spar.[2]

Recruitment materials emphasized that women could make more money in Spar jobs than they could as civilians and that they could build skills for careers after their service. They also promised women—and the broader American society—that military service would not undermine femininity. Spars were issued “$200 worth” of uniforms created by the fashion designer Mainbocher.

According to the Coast Guard, service also provided a sense of purpose. By joining, women could “free a man to fight,” serve their country, and win the war. One manual pledged that SPARS service offered “unusual opportunity for travel, new associations, increased self-confidence, and a fuller appreciation of the military might of the Nation and the courage and stamina of the men and women who make up its armed forces.”[3]

Recruiting materials targeted young white women, and most Spars were white. Despite discrimination, Latina, Asian American, and African American women also served. The SPARS only allowed Black women to enlist starting in the fall of 1944. Five women chose to join. The first Black recruit was Olivia Hooker, a survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre who later became a pioneering psychologist.

Office of War Information, US Government, public domain. Courtesy New York Public Library Schomburg Center, NYPG96-F156

Training

At first, SPARS recruits trained alongside WAVES at naval sites across the country. But it quickly became clear that they needed their own facility. Officer cadets went to the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. In May of 1943, the Coast Guard commissioned the Biltmore, a luxury hotel in sunny Palm Beach, Florida, as a training site for enlisted Spars.[5]

Every few weeks, a new crop of “boots” arrived for a whirlwind training program. The "indoctrination" process was designed to teach them to follow orders and obey military discipline. They learned Coast Guard history and protocol; underwent physical training and drills; and labored on seemingly endless cleaning duty.

Boots had to adapt quickly to military discipline—including marching to and from the nearby beach, where they conducted drills and sometimes enjoyed free time.

Spar Dorothy Wilkes remembered the occasional awkwardness of the experience:

Did you ever try to march in tennis shoes? It’s one thing to march in full uniform and quite another in a bathing suit topped by your playsuit, topped by your terry-cloth robe, and clutching a towel in the right hand. (Or was it the left? This was one of those things upon which no two people agreed. …)

If the trip to Sun and Surf was not chic, the return trip was pathetic, particularly when you had been surf bathing. Back you marched trailing sand, your hair dripping, and your bathing suit sending rivulets of water down your legs.

…Doing exercises upon the beach of the Atlantic Ocean you presented a picture that was intriguing to the jaded citizens escaping a New York winter to recline in the warmth and beauty of Palm Beach. Only alert and vigilant guards kept the fences from being lined with citizenry eager to applaud your efforts.” [6]

By early 1945, the SPARS had met its recruiting quotas and no longer needed the Palm Beach site. Training moved to Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, New York for the remainder of the war.

Courtesy the Tichnor Brothers Collection, Boston Public Library.

Duties and Experiences

At the end of training, Coast Guard leaders sorted women into groups based on job function. Forty percent became “yeomen,” performing clerical and administrative duties. Thirty percent were assigned as “storekeepers,” the Coast Guard term for logistics and procurement specialists. Many yeomen and storekeepers did work similar to what they had done before enlisting. Most of the rest went straight to duty, usually as “seamen second class” or “strikers.”

Women quickly proved their fitness for other kinds of work as well. Over the course of the war, Spars worked as photographers, cooks and bakers, pharmacy assistants, and drivers, among other roles. Through World War II, more than half of Coast Guard men ultimately went to sea. Women filled many of their jobs and entered new ones as new needs emerged. They worked at every Coast Guard station except Puerto Rico. In 1944, Congress lifted the ban on sending Spars overseas. About 200 went to Ketchikan, Alaska, and 200 more went to Hawaii.

Women lived in separate dormitories and ate in separate mess halls from male Guardsmen, but they interacted frequently on the job. The authors of Three Years Behind the Mast, a joint memoir of Spar life, recalled that “the attitude toward us ranged from enthusiastic reception through amused condescension to open hostility.”[7] Some men didn’t want sea duty and resented the arrival of women who were “freeing them to fight.” Others felt that they deserved faster promotions and begrudged Spars who rose through the ranks more quickly. Some simply believed that women should stay in the kitchen.

Spars faced a range of reactions from civilians as well. While the public often treated them with respect or curiosity, women in uniform also experienced street harassment and sexist jokes. Men hostile to working women accused them of sexual promiscuity.

“There was nothing surprising in any of the objections,” the authors reflected in Three Years Behind the Mast. “Any woman who tries to become part of a man’s world even in time of a great national emergency is automatically placing herself at the beginning of an obstacle course.”[8]

Postwar and Legacy

The arrival of “Victory over Japan Day” on August 15, 1945 prompted celebrations among the Spars. It also heralded an uncertain future for many servicewomen. The branch was set to be disbanded six months after the end of the war. On June 30, 1946, more than 10,000 Spars officially demobilized.

Some Spars were anxious to be free of military discipline and to return to civilian life.[9] Others, like some of their counterparts in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines, may have preferred to stay on. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act under pressure from servicewomen and military leaders. The legislation allowed women to serve as regular, permanent members of the US military. Technically, however, it did not apply to the SPARS. Unlike the other branches, the Coast Guard was officially run by the Department of the Treasury rather than the Department of Defense.[10]

Nevertheless, the Coast Guard reestablished the SPARS in 1949. The Coast Guard did not make a strong recruiting push to attract women. Only a few hundred former Spars rejoined.[11] The SPARS remained active until 1973, when Congress made Coast Guard women eligible to serve alongside men.

Women of the SPARS

[1] The all-caps acronym “SPARS” refers to the organization, while an individual member was known as a “Spar.”

[2] Mary C. Lyne and Kay Arthur,Three Years Behind the Mast (Washington, DC: US Coast Guard, 1946) 103.

[3] U.S. Coast Guard, “Facts about…SPARS” (1944), p. 6. https://gateway.uncg.edu/islandora/object/wvhp%3A5624#page/1/mode/1up

[4] Neil Genzlinger, "Olivia Hooker, 103, Dies; Witness to an Ugly Moment in History," New York Times, Nov. 23, 2018. Olivia Hooker, 103, Dies; Witness to an Ugly Moment in History - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

[5] The Biltmore Hotel, now Biltmore Condominiums, is adjacent to the Royal Poinciana Way Historic District in Palm Beach, added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 17, 2015.

[6] Lyne and Arthur, Three Years Behind the Mast, 32-33.

[7] Lyne and Arthur, 70.

[8] Lyne and Arthur, 71.

[9] Lyne and Arthur, 98-100.

[10] John A. Tilley. "A History of Women in the Coast Guard." Women (uscg.mil)

[11] Tilley, "A History of Women in the Coast Guard." Women (uscg.mil)

Cloutier, M.M. "Memory Lane: 'SPAR' partners: U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserve trained in Palm Beach." Palm Beach Daily News, Palm Beach, FL, Nov. 5, 2022. U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserve trained in Palm Beach (palmbeachdailynews.com)

Genzlinger, Neil. "Olivia Hooker, 103, Dies; Witness to an Ugly Moment in History." New York Times, Nov. 23, 2018.

Lyne, Mary C. and Kay Arthur. Three Years Behind the Mast: The Story of the United States Coast Guard SPARS. Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Guard, 1946.

"Manhattan Beach Goes Co-ed with the SPARS Moving In." New York Daily News, New York, NY, Mar. 8, 1945. 08 Mar 1945, 558 - Daily News at Newspapers.com

Public Relations Division, Women’s Reserve Division. A Preliminary Survey of the Development of the Women’s Reserve of the United States Coast Guard. Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Guard Historical Section, April 1946.

"Their War Too: U.S. Women in the Military During World War II, Part I." The Unwritten Record, National Archives and Records Administration, Mar. 22, 2018. Their War Too: U.S. Women in the Military During WWII. Part I – The Unwritten Record (archives.gov)

Thomson, Robin J. "SPARS: The Coast Guard & the Women's Reserve in World War II." SPARS (uscg.mil)

Tilley, John A. "A History of Women in the Coast Guard." Women (uscg.mil)

Vojvodich, Donna. “The Long Blue Line: ‘Sooner Squadron’—First Native American Women to Enlist in the Coast Guard.” United States Coast Guard. November 5, 2021. (The Long Blue Lione: Sooner Squadron.)

United States Coast Guard, “Facts about…SPARS,” 1944. https://gateway.uncg.edu/islandora/object/wvhp%3A5624#page/1/mode/1up

United States Coast Guard. "Women in the U.S. Coast Guard: Moments in History." Women in Coast Guard: Historical Chronology (uscg.mil)

Article by Ella Wagner, PhD, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. This article was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.