Last updated: April 27, 2025

Article

The Underground Railroad and Fort Sumter

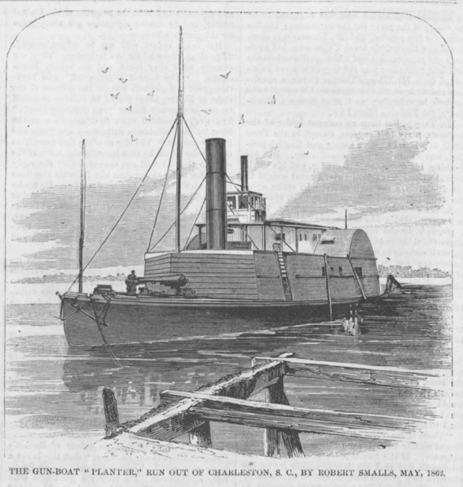

Harpers Weekly, June 18, 1862.

As a site that controlled the main shipping channel of Charleston Harbor, the fort served as an important obstacle to escapes from slavery. Despite this fact, at least three escapes, with at least 42 escapees, passed the guns of the fort on their way to freedom.

Why Charleston Harbor?

Confederate forces occupied Fort Sumter on April 14, 1861, after the opening shots of the war. However, just beyond Fort Sumter, a new possibility for freedom beckoned. Within a week of Fort Sumter’s occupation by the Confederacy, President Lincoln ordered the United States Navy to blockade the entire Southern coastline [1]. By July 1861, United States gunboats were off the coast of Charleston. [2]

Under the Confiscation Act of 1861, Confederates “shall forfeit [their] claim to such labor” of any enslaved person who encountered the US military. [3] In practice, US commanders could now declare escapees who reached US lines as contraband of war – a legal limbo that removed them from the reach of their enslavers without yet formally emancipating them. [4] Still, this would be the first time in the lives of Charleston’s enslaved workers that the possibility of freedom lay just miles away.

Escape!

It did not take long for escape attempts to begin. On April 28, 1862, fifteen enslaved workers escaped from Charleston Harbor!

To accomplish this feat, the escapees had to clear several hurdles. They left Charleston at approximately 9:30 PM on April 27, using a boat that belonged to the local Confederate quartermaster’s department. By about 2:00 AM on April 28, they had passed between Forts Sumter and Moultrie, and made it to the USS Bienville, located northeast of Sumter outside the harbor.

What we know of this escape comes from the original records of the Bienville. Their account, in addition to the above information, names two escapees, Allen Davis and Gabriel (no last name given), who each gave extensive intelligence to the US sailors on the Confederate defenses in the harbor. At least one of the escapees had been enslaved by Confederate General Roswell Ripley, and Gabriel had worked on pilot boats for twelve years, according to the account. [5]

This escape, unlike the subsequent escape of the Planter, was not highly publicized, and little information is available on the lives of the fifteen escapees.

The Planter

Less than a month after the escape to the Bienville, the harbor saw its most celebrated escape of the war. The escape’s leader, Robert Smalls, was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina, and was currently being “hired out” to the crew of the Planter [6]. The Planter was owned by a private citizen, John Ferguson, but was performing work for the Confederate government.

At night, the Planter docked at the Southern Wharf of Charleston. In a later account, escapee Alfred Gourdine reports that the plan took shape in early May. “The officers of the steamer commenced the practice of going ashore at night, and leaving the steamer in our charge, but fast to the wharf.” [7] Smalls conceived a plan of using their absence as an opening to sail the ship through the harbor to freedom.

If the escape was successful, Smalls would also be able to injure the Confederate war effort. By the night of May 13, 1862, the Planter was outfitted with six heavy artillery guns. Two were the ship’s armaments; the remaining four guns and a carriage were set to be delivered to gun positions in the harbor, including Fort Sumter. [8] [9]

The ship left the Southern Wharf at about 3:00 AM on May 13, and stopped at the North Atlantic Wharf to pick up family members [10]. In order to reach US gunboats, the Planter would have to pass under the guns of Fort Sumter. The “main ship channel” in and out of Charleston Harbor passed Fort Sumter on four of its five sides before turning south along Morris Island.

According to Gourdine, this would be the most perilous point of their journey:

“What we had talked over, and what every man fully realized, was that the real crisis would come when we passed Fort Sumter…if something happened and we refused to stop, we could count on all the big guns being turned loose on us. When we drew near the fort every man but Robert Small[s] felt his knees giving way and the women began crying and praying again.” [11]

Refusing to give in to the fear of Sumter’s guns, the Planter made its transit at about 4:15 AM, with Smalls giving the correct whistle signal [12]. The Confederate troops at Fort Sumter were none the wiser. According to a report by Maj. Alfred Rhett, commanding the Fort, “at 4:15 this morning the sentinel on the parapet called for the corporal of the guard and reported the guard-boat going out.” [13] The sentinel had mistaken the Planter for another vessel.

After transiting past Fort Sumter, the Planter’s crew reached the USS Onward, raising a white flag to prevent the US vessel from firing on them [14]. Sixteen people, including Robert Smalls, nine other crewmen, and six family members, had escaped from slavery. They had also delivered a working vessel, six Confederate cannons, and valuable military intelligence to the United States. In addition to securing their freedom, each crew member received a monetary reward for their actions. [15] [16]

For more information on Smalls’ later life and accomplishments, check out our site's Robert Smalls article!

New Opportunities for Escape

As the war continued, US military operations near Charleston expanded

opportunities for escapes from slavery. In September 1863, US forces were able to take control of Morris Island, just southwest of Fort Sumter. Control of this island allowed US forces to bombard the whole of Charleston Harbor with artillery fire, including Fort Sumter. It also meant that potential escapees could now set Morris Island as their goal, in addition to nearby US ships.

On May 6, 1864, escapees reached the US fortifications. US soldiers on Morris Island recorded that “twelve contrabands, eight men and four women, landed at Fort Strong [Wagner].” [17] The report mentions that one of the escapees had been enslaved by H.P. Lesesne, the Confederate commander of Castle Pinckney (another harbor fort).

These men and women would have had to go through the harbor to reach Morris Island, but would not have had to use Smalls’ path – instead, they could have used shallow water and smaller islands to reach the US troops.

Legacy of Freedom

The stories of these escapes illustrate the resourcefulness and courage of Black freedom seekers in Charleston Harbor. The escapes would have important consequences – for the new freedmen, but also for people across the nation.

While two of the three escapes discussed here remained relatively anonymous, Robert Smalls’ escape on the Planter became one of the most well-known escapes of the war. The story was prominently featured in Harper’s Weekly the following month, and he spoke publicly about it to audiences across the North. [18]

Smalls’ escape may have influenced the creation of Black US regiments. In August 1862, Smalls and a white officer met with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in Washington. [19] Following the meeting, Stanton authorized the raising of up to 5,000 Black troops in Beaufort, SC – one of the first such authorizations of the war. [20] By the summer of 1863, members of the 54th Massachusetts regiment fought under the US flag in Charleston Harbor.

Visitors to Charleston can learn about many aspects of the Civil War – through political causes, military battles, lives lost, and the meaning of freedom itself. These stories come together through the brave men and women who risked their lives to gain their freedom from slavery. No understanding of Charleston’s Civil War is complete without these stories.

Notes:

ORN: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.

ORA: The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

[1]: Lincoln, Abraham. “Proclamation 81 — Declaring a Blockade of Ports in Rebellious States.” Accessed via Gerhard Peters and John T. Wooley, The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/203023

[2]: Nank, Thomas E. “Naval Operations in Charleston Harbor.” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/naval-operations-charleston-harbor

[3]: “Chapter LX – An Act to Confiscate Property Used for Insurrectionary Purposes”. United States Congress, 6 Aug. 1861. Accessed via iowa.gov, https://history.iowa.gov/sites/default/files/history-education-pss-afamcivil-chaplx-transcription.pdf

[4]: Fling, Sarah. “Washington, D.C.’s ‘Contraband Camps’”. White House Historical Association, 22 Jul. 2020. Accessed via whitehousehistory.org, 6 Feb. 2024. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/washington-d-c-s-contraband-camps

[5]: ORN. Series I, Volume 12. Pp. 784-787.

[6]: “Robert Smalls”. National Park Service, 2022 March 18. https://www.nps.gov/people/robert-smalls.htm

[7]: “A Strike For Freedom”. Detroit Free Press, 1893 Dec 17, p. 30. https://www.newspapers.com/article/detroit-free-press-account-of-robert-sma/135740664/

[8] “Disgusting Treachery and Negligence.” The Charleston Mercury, 1862 May 14, p. 2. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-charleston-mercury-disgusting-treac/135741112/

[9]: ORA. Series I, Volume XIV. Pp. 14-15.

[10]: “Stole a Whole Vessel.” The Boston Globe, 1903 Oct 8, p. 3. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-boston-globe-boston-globe-interview/135753550/

[11]: “A Strike For Freedom”.

[12]: Ibid.

[13]: ORA. Series I, Volume XIV. P. 15.

[14]: ORN. Series I, Volume 12. P. 821.

[15]: ORN. Series I, Volume 12. Pp. 821, 825.

[16]: Lineberry, Kate. Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to Union Hero. Picador St. Martin’s Press, 2017. P. xi-xii.[17]: “Interesting from Charleston Harbor.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 27 May 1864. P. 2. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-philadelphia-inquirer-charleston-har/139883062/

[18]: “The Steamer ‘Planter’ and Her Captor.” Harpers’ Weekly, 1862 June 14. Accessed via HathiTrust, “Harpers Weekly v6 1862”, pp. 347-348. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021016210&seq=347

[19]: French, Mansfield, to George Whipple, 1862 Aug 23 and 1862 Aug 28. American Missionary Association Archives, nos. HL 4517 and 15901, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans. Cited by Lineberry, Cate, Be Free or Die, p. 118 & p. 250.

[20]: ORA. Series I, Volume XIV. Pp. 377-378.