Last updated: October 26, 2021

Article

“She is a woman who can take care of herself:” The Story of Jane Johnson

Boston served as a destination for many people escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers arriving in the city found that Boston's tightly knit free Black community provided support and a welcome sanctuary as they began their new lives. This article highlights the journey of a freedom seeker, Jane Johnson, who escaped to Boston. To explore additional stories, visit Boston: An Underground Railroad Hub.

When Jane Johnson's enslaver took her and her two sons to Philadelphia, Johnson saw an opportunity to escape. She contacted local abolitionists who escorted her and her sons away from her enslaver. Her bold escape led to the arrest and trial of her accomplices. During the trial, she bravely testified against her enslaver. Following her escape, Johnson became active in Boston's Black Beacon Hill community and assisted other enslaved people on their path to freedom.

Explore the story map below to learn about Jane Johnson's journey to freedom. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll down to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes

[1] Frederick Douglass' Paper (Rochester, New York), September 14, 1855.

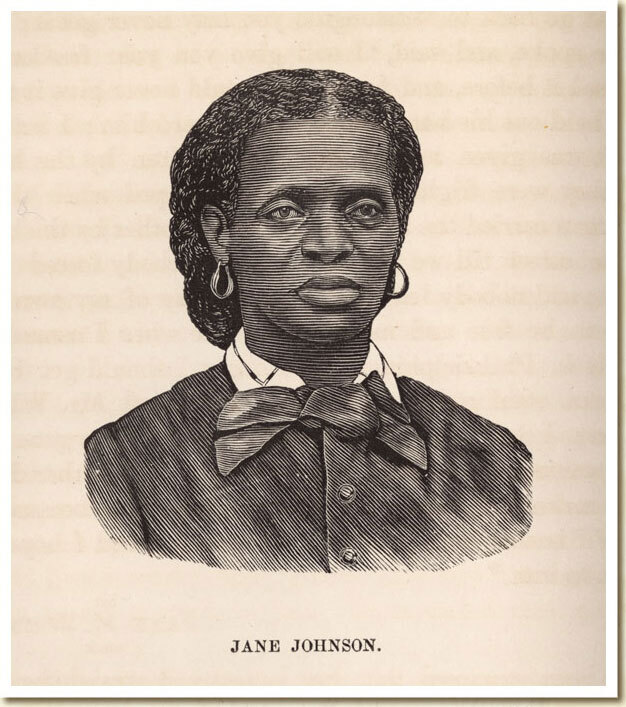

Image: William Still, "Engravings by Bensell, Schell, and others," Still's Underground Rail Road Records: With a Life of the Author. Narrating the Hardships, Hairbreadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom (United States: William Still, 1886), accessed November, 2020, https://archive.org/details/undergroundrailr00stil/page/n117/mode/2up.

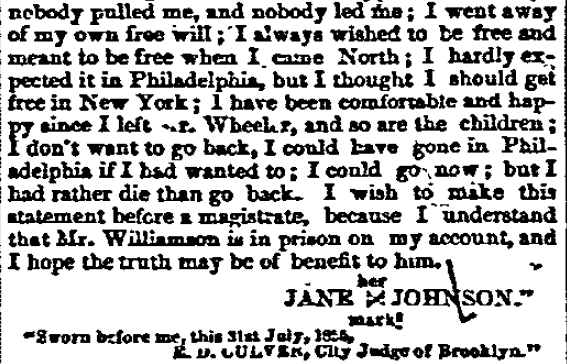

[2] Katherine E. Flynn. “Jane Johnson, Found! But Is She ‘Hannah Crafts’?” in In Search of Hannah Crafts: Critical Essays on The Bondwoman’s Narrative, ed. by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Hollis Robbins (New York: BasicCivitas Books, 2004), 398-399.

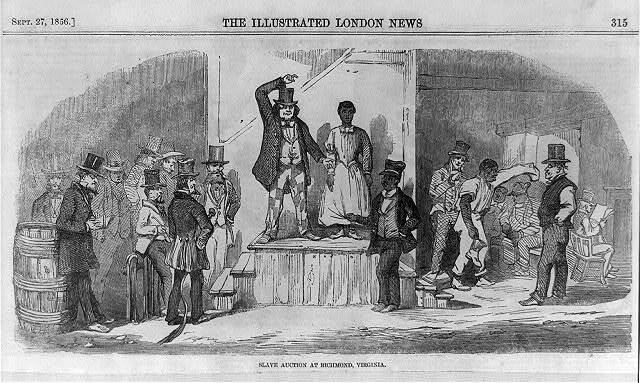

Image: Slave auction at Richmond, Virginia, Richmond Virginia, 1856, Photograph, accessed November, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/98510266/.

[3] William Still, The Underground Railroad (Medford, New Jersey: Plexus Publishing, 2005), originally published in 1872, 58-59.

[4] Flynn, "Jane Johnson, Found!," 393.

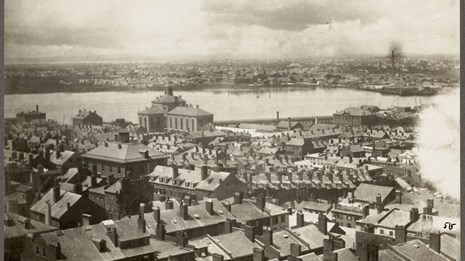

Image: E. Sachse & Co. View of Washington / drawn from nature and on stone by E. Sachse ; lith. and print in colors by E. Sachse & Comp. United States Washington D.C. District of Columbia Washington, ca. 1852 (Baltimore, Md.: Published and sold by E. Sachse & Co), Photograph, accessed November, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/98515951/.

[5] Still, The Underground Railroad, 54-56.

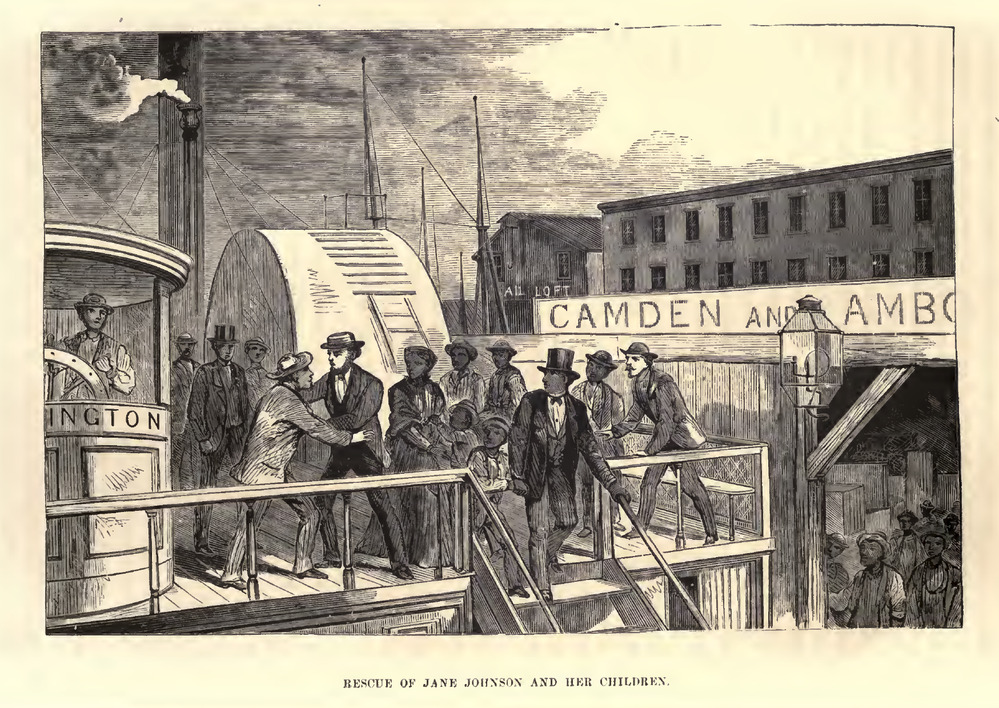

Image: William Still, "Engravings by Bensell, Schell, and others," Still's Underground Rail Road Records: With a Life of the Author. Narrating the Hardships, Hairbreadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom (United States: William Still, 1886), accessed November, 2020, https://archive.org/details/undergroundrailr00stil/page/n109/mode/2up.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Phil Lapsansky, "The Liberation of Jane Johnson," The Library Company of Philadelphia, accessed October 2020, http://librarycompany.org/JaneJohnson/.

[8] Still, The Underground Railroad, 54-56.

[9] Daily Atlas (Boston, Massachusetts), August 2, 1855.

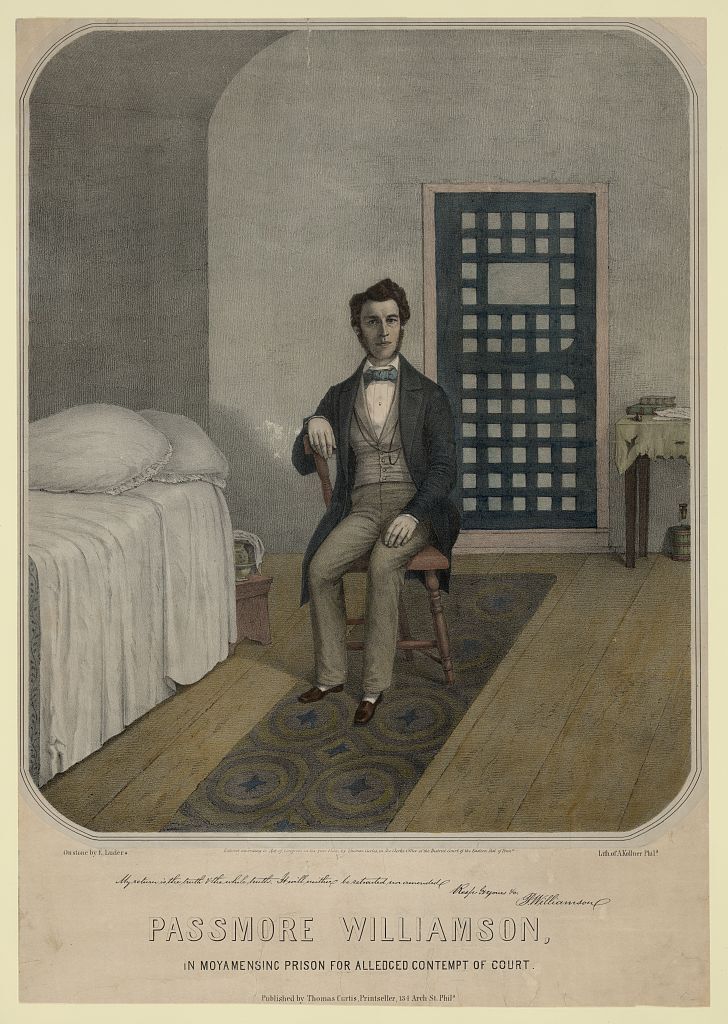

Image: Emil Luders and Augustus Kollner, Passmore Williamson, in Moyamensing Prison for alledged contempt of court / on stone by Emil Luders ; lith. of August Kollner, Phila. , ca. 1855 (Philadelphia: Published by Thomas Curtis, printseller, 134 Arch St., Phila) Photograph, accessed November, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003689277/.

[10] William Cooper Nell, Selected Writing 1832-1874, ed. by Dorothy Porter Wesley and Costance Porter Uzelac (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2002), 420.

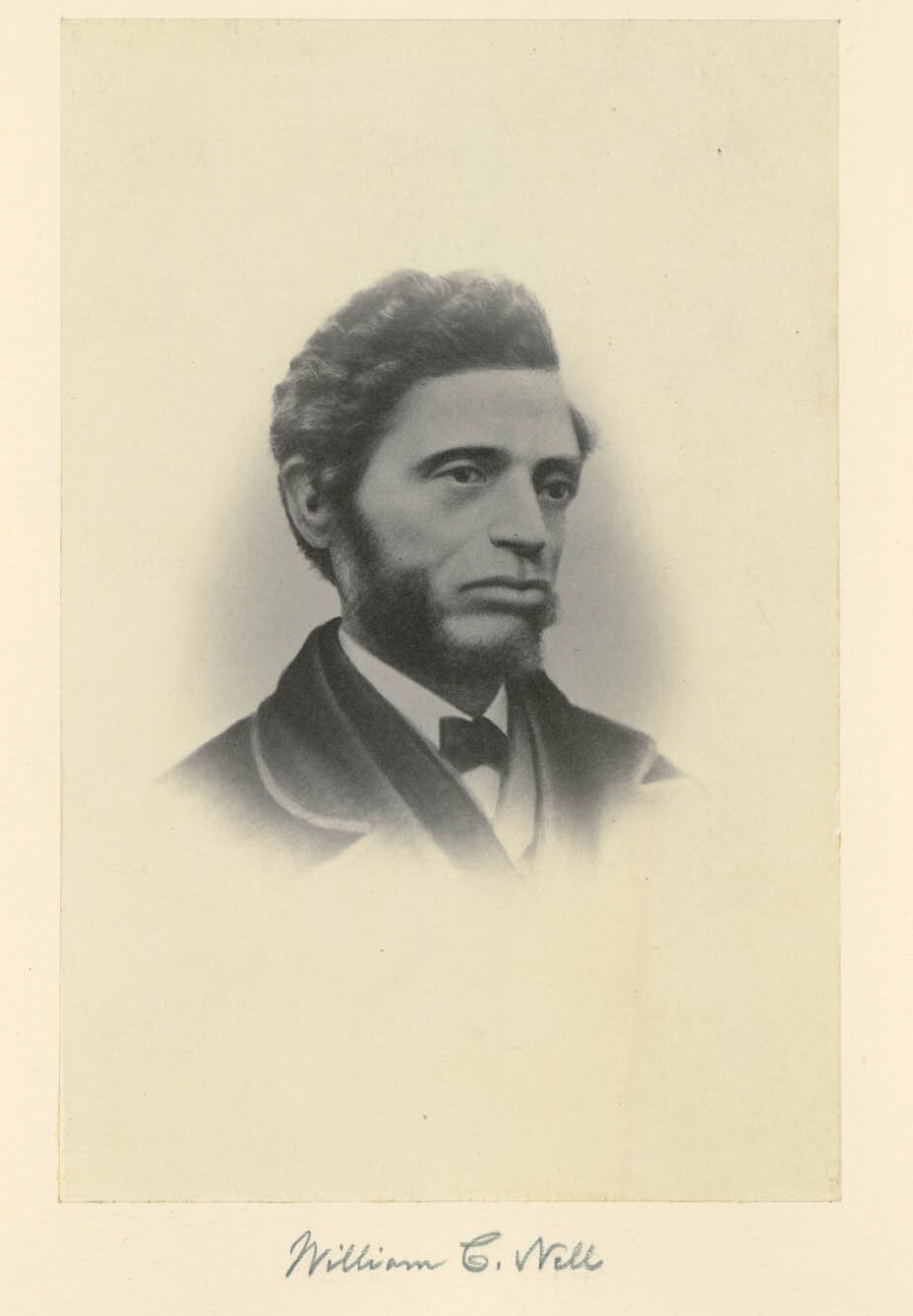

Image: William Cooper Nell, Photograph, Massachusetts Historical Society Collection, accessed November, 2020, http://masshist.org/database/1338.

[11] Ibid., 432.

[12] Ralph Lowell Eckert, “Antislavery Martyrdom: The Ordeal of Passmore Williamson,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 100, No. 4 (Oct., 1976): 529.

Image: Congress Hall, the State House and Old City Hall, Chestnut Street at 6th, c. 1855, ca. 1855, Salt Prints (Philadelphia, PA: Free Library of Philadelphia), accessed November, 2020, https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/2586.

[13] The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), September 7, 1855.

[14] Narrative of Facts in the Case of Passmore Williamson, Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society (Philadelphia, 1855), https://archive.org/details/narrativefactsi00unkngoog/mode/2up, 16.

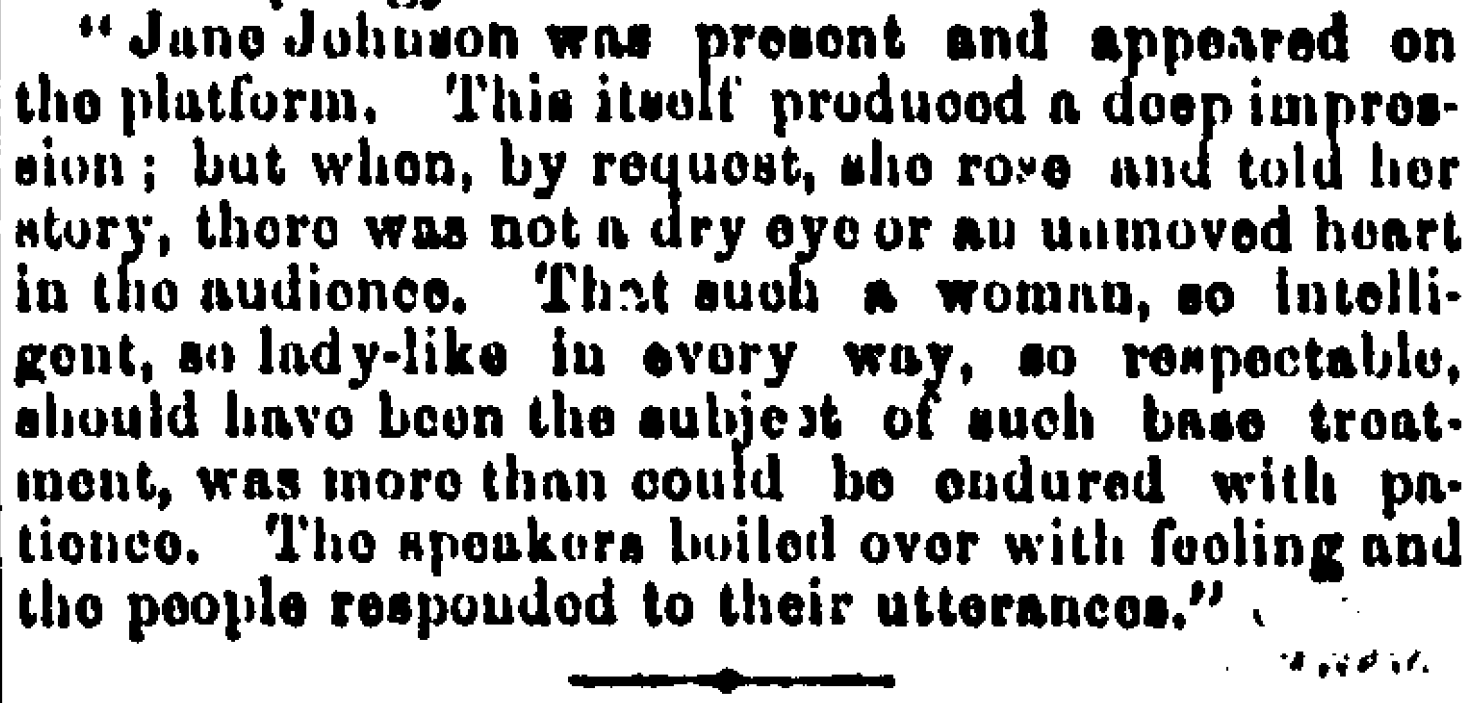

[15] Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem, Ohio), September 15, 1855.

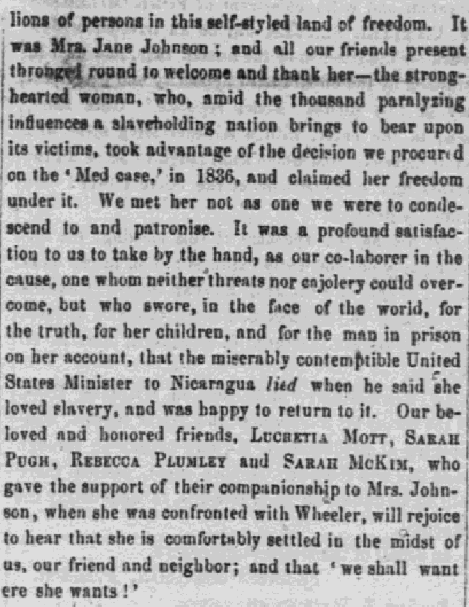

Image: Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem, Ohio), September 15, 1855.

[16] Philadelphia Inquirer, October 13, 1855.

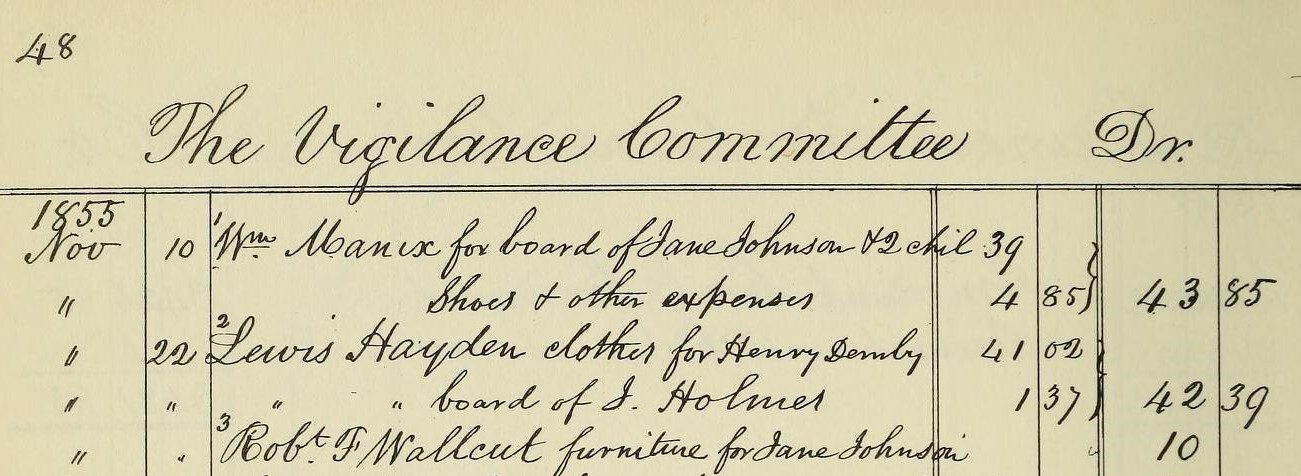

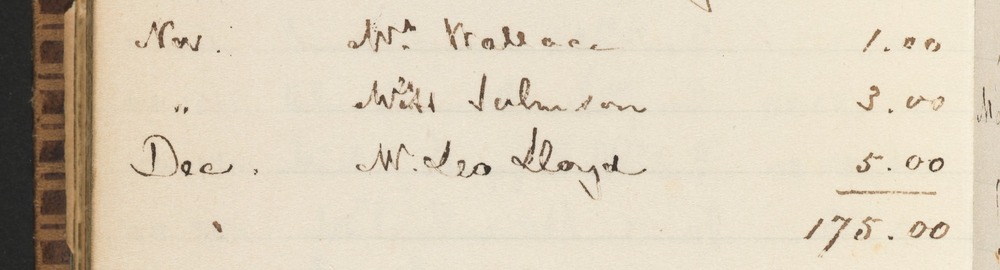

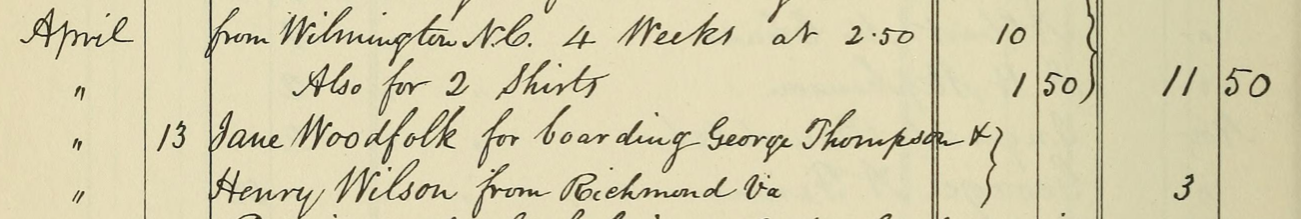

Images: Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, selection from 1855, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, W.B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives, Wilkens Library, Cape Cod Community College, accessed November, 2020, https://archive.org/details/drirvinghbartlet19bart/page/48/mode/2up; Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Papers, 1819-1928. MS Am 1340 (152), Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. p. 180, accessed November, 2020, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:9028239$190i.

[17] Eric Foner, Gateway To Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2015), 144.

[18] The Liberator, January 25, 1856.

Image: The Liberator, January 25, 1856.

[19] Flynn, "Jane Johnson, Found!," 376.

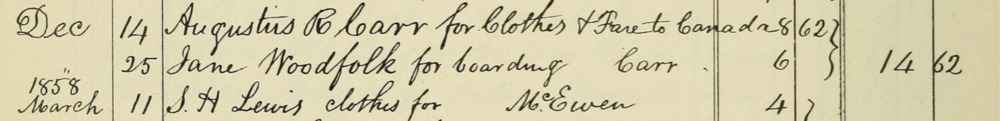

Images: Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, selection from 1857, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, W.B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives, Wilkens Library, Cape Cod Community College, accessed November, 2020, https://archive.org/details/drirvinghbartlet19bart/page/n57/mode/2up; Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, selection from 1859, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, W.B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives, Wilkens Library, Cape Cod Community College, accessed November, 2020, https://archive.org/details/drirvinghbartlet19bart/page/n61/mode/2up.

[20] Nell, Selected Writing 1832-1874, 452.

[21] Flynn, "Jane Johnson, Found!," 379.

[22] Kathryn Grover and Janine V. Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," Boston African American National Historic Site, (2002), 105-106, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/ugrr/discover_history/upload/boafsrs.pdf.

[23] Flynn, "Jane Johnson, Found!," 381.

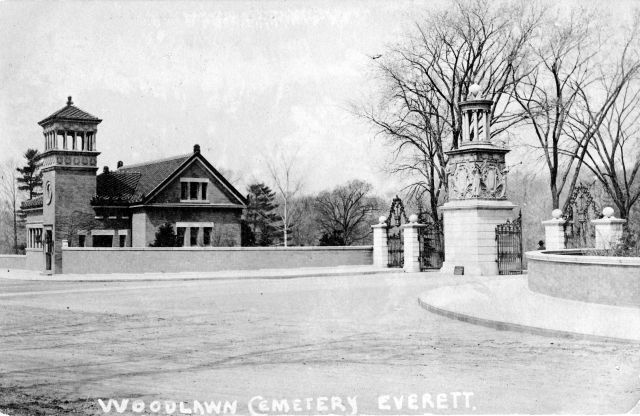

Image: Gustav F. Braun, “Woodlawn Cemetery Everett,” NOBLE Digital Heritage, accessed November, 2020, https://digitalheritage.noblenet.org/noble/items/show/612.