Part of a series of articles titled The History of Slavery in St. Louis.

Previous: Slavery and the Law

Next: Resisting Slavery

Article

Missouri Historical Society

Since enslaved Black Missourians were considered property under state law, they faced the prospect of being sold and separated from their families during slave auctions. For example, William Wells Brown recalled how he never saw several of his siblings again after they were sold. As the cotton industry grew in Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and other Deep South states in the 1830s, enslaved Missourians constantly feared being sold down the Mississippi River.

Bernard Lynch was the most prominent trader of enslaved people in St. Louis. His primary trade site was known as “Lynch’s Slave Pen” and was located at 5th and Myrtle streets. This prison incarcerated enslaved people about to be sold at auction, freedom seekers who had been captured, and free Blacks who had violated the law. These people were regularly subjected to violent punishments by Lynch’s employees. Auctions occurred at least once a week near the St. Louis Courthouse.

Lynch abandoned his prison when the U.S. military seized it at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. Ironically, the U.S. military kept Confederate prisoners at the site during the war. As St. Louis historian Angela da Silva points out, “Bernard M. Lynch’s slave pen turned into a prison for the same people who went shopping there [before the war].”

Today, the original location of Lynch’s Slave Pen is the site of Ballpark Village.

Missouri Historical Society

Bernard Lynch used this oak box to store cash from his slave trading business. It is the only existing artifact connected to Lynch's business.

Missouri State Archives

The buying and selling of humans as property constitutes one of the greatest atrocities in human history. Enslaved St. Louisans endured many traumas during the slave trading process. Appraisers (people who put a monetary value on property) inspected and sometimes assaulted enslaved people while determining how much they could be sold for on the auction block. During sales, enslaved people were often forced to be naked or wear very little clothing in front of large audiences. Many auctions resulted in the breaking up of enslaved families.

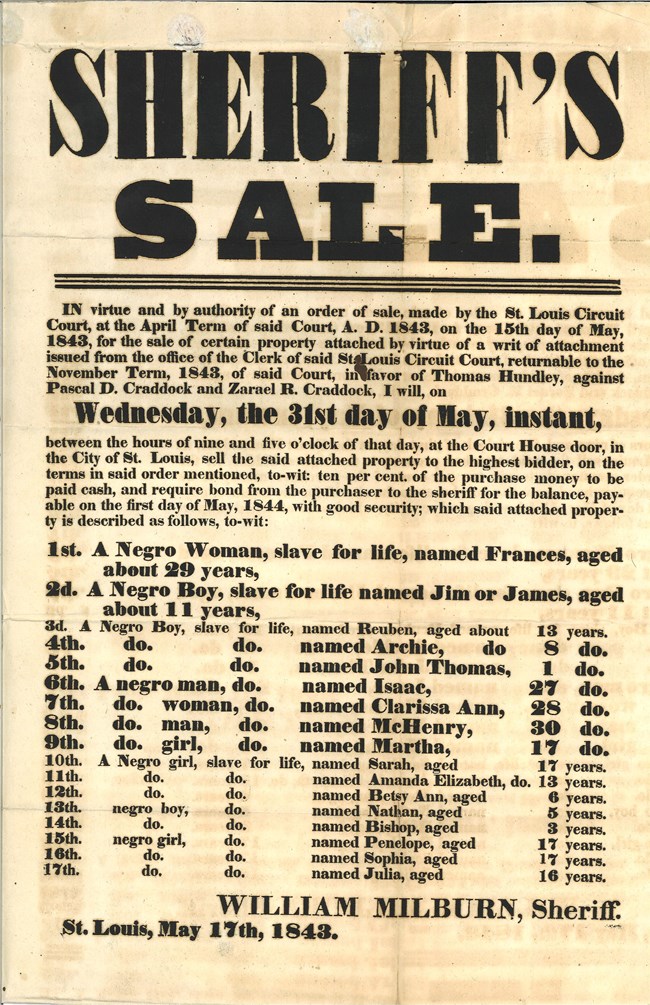

On May 31, 1843, the St. Louis County sheriff oversaw a large auction of seventeen enslaved people at the St. Louis Courthouse. Ranging in age from one to thirty years old, they were placed on the auction block and sold to the highest bidder. Some were undoubtedly sold away from St. Louis to other cities and may have never seen their family again. After the Civil War, it was common for newspapers—especially those run by Black journalists writing for Black subscribers—to post advertisements from newly-freed residents looking to reunite with their families.

Few visual reminders of the slave trade remain in St. Louis today. In 2021, Missouri State Representatives Rasheen Aldridge and Trish Gunby called for a memorial at the original location of Lynch’s Slave Pen to commemorate the city’s enslaved residents who were victims of the slave trade. Since then, a dedicated group of individuals continues to advocate for a marker and is working to secure ownership and funding.

State Historical Society of Missouri

St. Louis's most proslavery, pro-Democrat party newspaper in the 1850s and 1860s was the confusingly-titled Missouri Republican. Bernard Lynch regulary posted advertisements for his business in the newspaper. This advertisement from the August 4, 1860 edition reads as follows:

B.M. Lynch has removed to his large, airy, new quarters, No. 57 South Fifth street, corner of Myrtle. He will pay the highest prices known to the trade for all descriptions of negroes suited to the Southern markets. Will also board and sell on commission. Thankful for past favors, he solicits a continuance of public patronage. Negroes on hand and for sale at all times.

Another advertisement from an anonymous patron underneath Lynch's advertisement reads:

For Sale--A very likely intelligent MULATTO BOY, between ten and twelve years of age. Is a good hand to wash dishes, wait on the table, take care of children, run on errands, &c. Address postoffice, box 2,577.

Thomas Satterwhite Noble's first professional painting was "Last Sale of the Slaves," which he completed in 1865. This oil painting depicts an auction near the steps of the St. Louis Courthouse that reportedly occured on January 1, 1861. In 2011, Gateway Arch National Park hosted a slave auction reenactment at the courthouse.

Interestingly, Noble served in the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Part of a series of articles titled The History of Slavery in St. Louis.

Previous: Slavery and the Law

Next: Resisting Slavery

Last updated: January 3, 2024