Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 16, No. 1, Spring 2024.

Article

The Peale Museum: America’s First Natural History Museum Features a Mastodon

Article by Megan Rich, NPS Partner - Researcher

American Geosciences Institute

for Park Paleontology Newsletter, Spring 2024

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

Independence National Historical Park is nicknamed “America’s most historic square mile,” but few of the millions of visitors may know the park also made history by once displaying a mastodon skeleton in Independence Hall. There are a number of paleontological specimens associated with the park, including a mastodon tooth which may have belonged to Benjamin Franklin’s collection as well as Ordovician fossils found in the flooring of the Second Bank of the United States. While these have been recognized relatively recently, the historic foundations of paleontology in America can be traced back to this square mile in Philadelphia where the earliest natural history museum in the United States once existed.

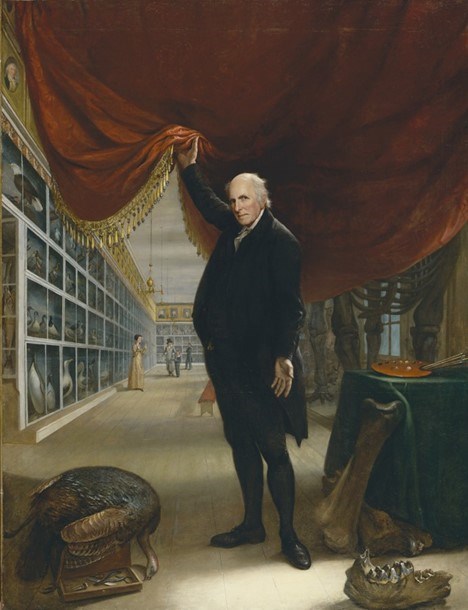

Charles Willson Peale established his famous Philadelphia Museum out of his family home in 1784, calling it “A Repository for Natural Curiosities.” Peale was an artist by profession, painting portraits of numerous figures from the Revolutionary War and young republic, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis, and William Clark, and he displayed his work in the museum gallery. In 1783, Peale was asked to draw the fossilized mastodon bones recovered from Big Bone Lick in the Ohio River Valley—the fossil site that many scholars consider the birthplace of vertebrate paleontology in the New World. The attention the Big Bone Lick fossil discovery received inspired Peale to one day display a fossil skeleton alongside his art.

Maryland Historical Society.

As his museum collection and number of visitors grew, Peale moved his museum into a bigger venue in Philosophical Hall, the headquarters of the American Philosophical Society (APS). The APS, led by Thomas Jefferson from 1797 to 1814, greatly supported Peale and other contemporary scientists. Jefferson, who was deeply engaged in scholarly debates with the Comte de Buffon, sought to prove that the French naturalist’s theory of New World fauna being weaker than those of Europe was incorrect. Many Americans at the time were riveted by stories of the "American incognitum", the mysterious name given to the unidentified beasts we know as mastodons. These bones had been found periodically in the country since the first mastodon tooth was documented in 1705, and the APS was keen on acquiring a complete skeleton.

In early 1801, news came to Philadelphia of mastodon remains found at the farm of John Masten in the Hudson River Valley, downstream from where the first tooth was found nearly a century before. The APS loaned Peale $500 to support his excavation and transport of the skeleton. Peale used the funds to hire workers and bring considerable equipment to the marl pit excavation site, including pumps, ropes, pulleys, and augers. He provided a detailed report of his field notes to Jefferson and returned with two partial skeletons from what is considered to be the first paleontological expedition in the newly formed US.

American Philosophical Society Museum.

With the bones back in Philadelphia, Peale and his team faced the task of reassembling a monster they had never physically seen. The similarities of the American incognitum to modern elephants and Siberian mammoths were well-documented, but the tusks and shape of the teeth led the team to believe the mastodon was carnivorous. They incorrectly placed the tusks inverted like that of a walrus and marketed the display as a fierce predator, much to the awe of museum visitors. For a few missing bones, Peale used bilateral symmetry and other collected bones to carve scientifically accurate replacements out of wood, a then-novel technique similar to modern conservation methods. Once completed, Peale’s mastodon was the second fossil skeleton ever to be reassembled, and the first in America.

Library Company of Philadelphia.

In support of this great achievement, Peale was aided by a team that included his son Rembrandt, the Philadelphia sculptor William Rush, and the enslaved man Moses Williams, a talented silhouette artist and the first black museum professional in US history. Williams was instrumental in the assembly process as Peale would later write, “[Williams] fitted pieces together by trying, [not] the most probable, but the most improbable position, as the lookers-on believed... Yet he did more good in that way than any one among those employed in the work.” The display was unveiled on Christmas Eve day in 1801. To promote the exhibit, Peale sent out Williams in feathered headdress on a white horse to parade through the streets accompanied by a trumpeter. Handbills were distributed to the populace featuring the Shawnee legend of a thundering monster from “ten thousand moons ago.” The opening was wildly successful.

The following year, the Philadelphia Museum expanded again, into both the Philosophical Hall and the Pennsylvania State House, now known as Independence Hall, the same building that witnessed such historical moments as the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The museum relocated to Independence Hall fully in 1810, where it would continue to be operated for the next decade. After Peale’s death in 1827, the museum was maintained by Peale’s children until it eventually ran out of funding. The museum portrait collection was sold at auction, with a third of Peale’s artwork purchased by the city of Philadelphia where it is presently under NPS stewardship and exhibited in Independence National Historic Park’s Second Bank. Most of the natural history collection was sold off to P.T. Barnum and later destroyed in a fire. The mastodon skeleton displayed in Peale’s museum was shipped to Europe, where it was eventually purchased for the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, Germany, in 1854. There, Peale’s mastodon remains on display to this day.

Spurred by the Enlightenment, Peale and his museum embraced curiosity and open science, centering around a uniquely American attraction. Contemporary American museums were interested in spectacles that could turn a profit, while European museums had an elitist reputation, prioritizing collection and research among intellectuals over education of the public. Peale sought to find a balance, and his work would later be emulated by museums globally. Peale valued scientific advancement, and his museum was among the first to implement Linnaean taxonomy, labeling his specimens in Latin, French, and English. However, he did not lose sight of the importance of sharing his passion with patrons. He blended his scientific inclinations with his artistic talent, pioneering the creation of dioramas of animals within habitat groups and illuminated by artificial light. His creativity in communicating science left an indelible mark on the history of museums and interpretation.

New-York Historical Society.

Without the star of the show, Peale’s Museum may not have had the fame or longevity which allowed him to set such precedents. The mastodon became an American symbol of fortitude and the mascot of American paleontology. Jefferson’s interest in the fossils and in stories recounted by Native Americans spurred the President’s interest in commissioning Lewis and Clark’s expedition, which was partially funded by the APS just a few years later, laying the groundwork for the next century of American scientific exploration. Peale’s son Rembrandt would later describe his father’s mastodon as “the first of American animals, in the first of American museums.” Peale never received full government support to turn his museum into America’s national museum as he wished for, but he inspired his many successors in museum management and paleontology. Around two decades after his death, the Smithsonian Institution was established “for the increase and diffusion of knowledge” in a format first envisioned and strived for by Peale. The ensuing dedication to exploration recognized at the national level included that of a man and his mastodon in Independence Hall.

Suggested Readings

-

DuBois Shaw, G. (2005). Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles: Silhouettes and African American Identity in the Early Republic. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 149(1), 22–39.

-

Freise, S. (2020). “The Second Bank of the United States: Ordovician Fossils in 19th Century Flooring.” Park Paleontology Newsletter.

-

Mayor, A. (2005). Fossil Legends of the First Americans. United States: Princeton University Press.

-

Peale, R. (1803). An historical disquisition on the mammoth, or, great American incognitum, an extinct, immense, carnivorous animal, whose fossil remains have been found in North America. (Vol. 15). E. Lawrence.

-

Santucci, V.L. (2017). Preserving fossils in the National Parks: A History. Earth Science History. 36(2): 245-285.

-

Sellers, C.C. (1980). Mr. Peale's Museum: Charles Willson Peale and the First Popular Museum of Natural Science and Art. United Kingdom: Norton.

-

Semonin, P. (2000). American Monster: How the Nation's First Prehistoric Creature Became a Symbol of National Identity. New York University Press.

-

Simpson, G.G. and Tobien, H. (1954). The rediscovery of Peale’s mastodon. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 98, No. 4, 279-281.

-

Spamer, E. (2018). “When is a Mastodon Not?” American Philosophical Society.

-

Yochelson, E.L. (1992). Mr. Peale and his mammoth museum. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 136, No. 4, 487-506.

Related Links

-

Independence National Historical Park (INDE), Pennsylvania—[INDE Geodiversity Atlas] [INDE Park Home] [INDE npshistory.com]

-

Park Paleontology News—The Second Bank of the United States: Ordovician Fossils in 19th Century Flooring

Last updated: April 3, 2024