Last updated: January 8, 2025

Article

The Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial and the Underground Railroad

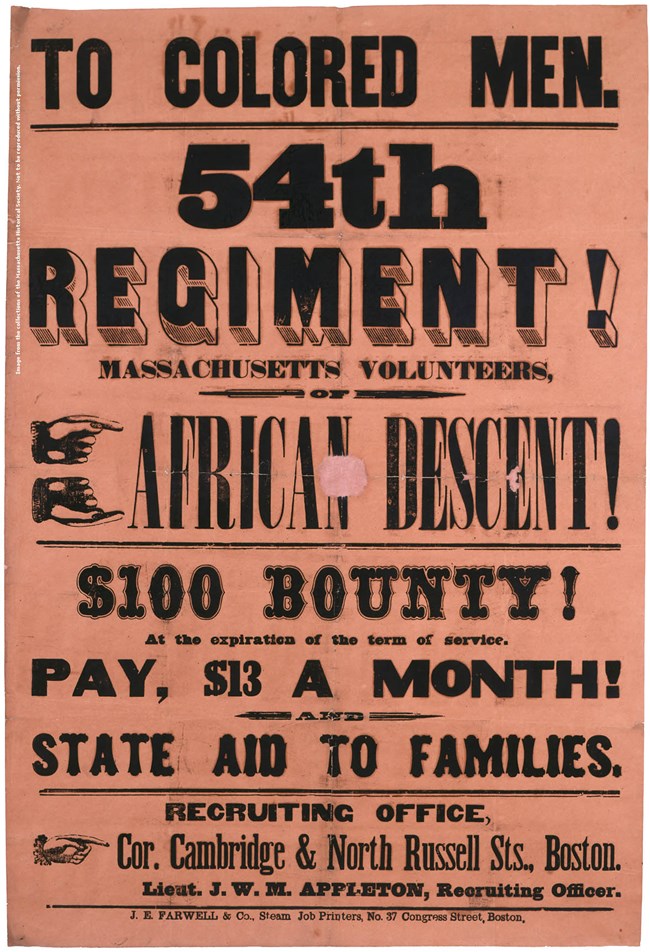

The history of the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial is deeply intertwined with that of the Underground Railroad. Though the 54th drew most of its soldiers from the free states, many southern born, some of whom had fled enslavement, helped fill the ranks of the regiment. Both the memorial and the regiment have strong connections to freedom seekers and their allies on the Underground Railroad.

Massachusetts Historical Society.

Establishing the Regiment

In 1863, Governor John Andrew secured permission to organize the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Prior to his election as Governor, Andrew served in several Vigilance Committees that assisted freedom seekers in Boston. Lewis Hayden, Boston's most prominent Underground Railroad operative, is often credited with giving Andrew the idea to form a Black regiment, though as historian Stephen Kantrowitz states, "this was too widespread a notion to belong to any one man."[1] According to one account, Andrew asked Hayden:

'Mr. Hayden, what in your opinion is the course the National Government ought to pursue to bring this terrible war to a successful termination.' 'Put colored troops in the field, sir,' was Mr. Hayden's reply. The governor was forcibly struck by the answer.[2]

Hayden and his wife Harriet, who had both escaped slavery on the Underground Railroad, sheltered scores of freedom seekers in their Boston safe house. Hayden became an ardent supporter and recruiter for the regiment from its earliest days.

Other freedom seekers and their allies also supported and recruited for the regiment. For example, in western Massachusetts, Henry S. Jackson, who had escaped slavery and settled in Pittsfield received "a commission to recruit for the 54th Regiment, [and] has been indefatigable and very successful ever since."[3] Outside of Massachusetts, Frederick Douglass, himself a prominent freedom seeker and Underground Railroad operative, also provided crucial support as a recruiter for the 54th regiment.[4]

Freedom Seekers in the Regiment

More than twelve hundred men ultimately comprised the regiment over its two year history. Estimates as high as 80% of these soldiers came from the northern states and had not experience slavery firsthand.[5] According to Captain Luis F. Emilio, in his regimental history A Brave Black Regiment, "Only a small portion had been slaves."[6] However, Emilio may not have considered that many of the recruits hid their formerly enslaved status given the uncertainty of the war and the Fugitive Slave Law.[7] Historian Edwin S. Redkey stated: "After the war, with slavery ended and the Fugitive Slave Law just a harsh memory, the men could talk more freely about their slave origins."[8] He argued that since more than 300 men in the regiment had been born in the South, it "seems reasonable to assume that perhaps half of these Southern men, at least 160, had been born into slavery and had somehow made their way north to freedom."[9]

It is difficult to ascertain just how many of the 54th had been born enslaved. Though many listed birthplaces in the South, that does not necessarily equate to being born enslaved. Furthermore, they may have deliberately given false information to their recruiters to protect themselves. It is even more challenging to determine how many of these men had fled slavery on the Underground Railroad. The following, however, are confirmed stories of men of the 54th that had emancipated themselves by escaping:

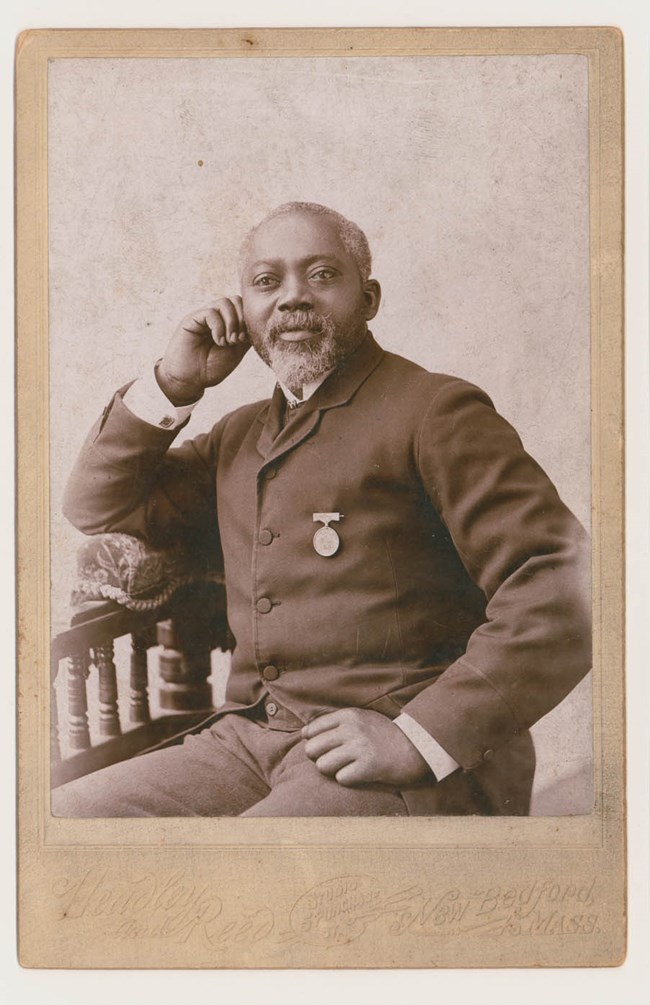

Massachusetts Historical Society

William H. Carney is perhaps the most famous member of the 54th Regiment and certainly its most famous freedom seeker. Born enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia, Carney escaped to New Bedford, Massachusetts in the late 1850s. Celebrated for saving the regiment's flag during its assault on Fort Wagner, Carney provided only murky details of his early life when asked by his commander to provide a biographical sketch. His military records indicate his birthplace as New Bedford.[10] Historian Kathryn Grover suggested, "with the outcome of the war highly uncertain, Carney probably lied to conceal his true status, as other fugitives in the regiment also did." Only later did he publicly reveal his background as a formerly enslaved freedom seeker who had "'confiscated himself.'"[11]

Twenty-three year-old Charles Reason enlisted in the 54th in Syracuse, New York. Severely injured at Fort Wagner, Reason had his arm amputated in a nearby hospital. Dr. Esther Hill Hawks asked him if she could contact his parents. Only then did he confide to her that he escaped from slavery in Maryland "'only a few years ago.'" He made his way to Syracuse and worked on a farm, pretending to be freeborn from Alabama so as not to reveal his identity as a fugitive. He enlisted in the 54th and claimed Syracuse as his birthplace.[12] "'As soon as the government would take me I came to fight,'" he said, "'not for my country, I never had any, but to gain one.'"[13]

Writer Martha Nicholson McKay shared the story of Milton Robinson who worked as a "helper in the yards and gardens" in her Indianapolis neighborhood. Cruelly treated while enslaved, Robinson fled from his Kentucky enslaver and attached himself to an officer in the Indiana troops. He eventually made his way to Boston "to achieve what to him was the greatest of earthly honors, recognition as a soldier in the Northern army."[14]

Soldier Jermain Matthews recalled fleeing enslavement in the South and becoming a "'free man.'" After self-emancipating, he said that he "'solemnly vowed to devote my whole life to best serving my people.'" Despite his fiancé's fear that he might die fighting "'for the white man's country,'" he joined the 54th Regiment.[15]

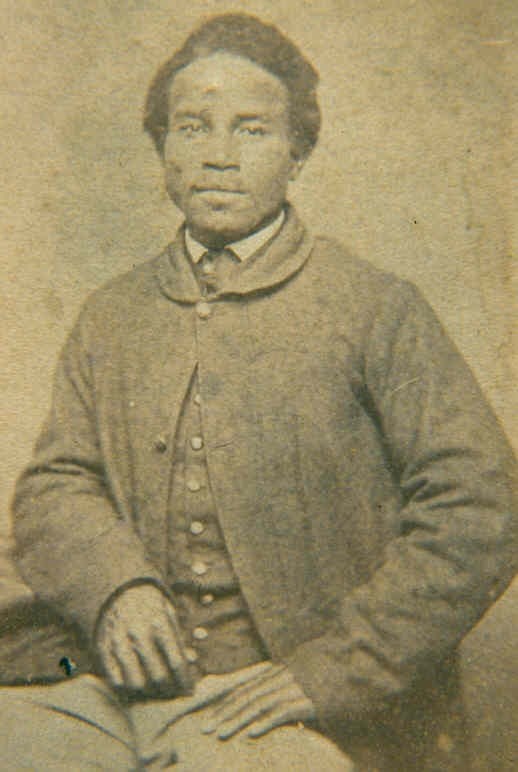

National Park Service (FRDO 4921)

Enslaved in Arkansas, Thomas Betts had been sent to a Confederate work crew to help build Fort Donelson in Tennessee. Once there, he ran away while gathering firewood and served for a time as a cook in an Ohio regiment. In Columbus, Ohio, he met recruiters for the 54th and enlisted.[16] Like others in the regiment, he concealed his background and listed his birthplace as Zanesville, Ohio.[17]

Nathan Sprague fled enslavement in Maryland and went north to Rochester, New York, where he worked as a gardener. There he met and became engaged to Rosetta Douglass, Frederick Douglass' eldest daughter. The family did not fully support the union at first. According to historian Douglas Egerton, the family eventually approved of the marriage provided Sprague prove his worth by joining the 54th, which he ultimately did.[18]

Other evidence suggests more soldiers in the 54th had been enslaved and had secured their freedom on the Underground Railroad as Carney and others did. The Oberlin (Ohio) News reported, "Fourteen of our colored citizens have answered to the call of good Gov. Andrew, of Massachusetts, and enrolled themselves in the black regiment...Three are fugitives, and three emancipated slaves."[19] The National Anti-Slavery Standard wrote that "the best class of men came forward and enlisted, not only from Massachusetts, but from other States, and fugitives from Canada came to join their Northern brethren to fight under the 'Flag of the Free.'"[20] Sergeant George Stephens of Pennsylvania acknowledged "In truth there are necessarily some few fugitives here..."[21] Clearly, the 54th included freeborn men from the North and South, as well as formerly enslaved men, some of whom had secured their freedom through escape on the Underground Railroad.

The Memorial's Underground Railroad Connections

The Underground Railroad connections to the regiment continued with the creation of the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial. Immediately following the death of Colonel Shaw and many men of the 54th at Fort Wagner in July 1863, efforts began to find an appropriate way to honor their memory. In Boston, Joshua B. Smith, a successful caterer, served as the primary driver of the commemoration effort. Smith, who may have escaped slavery himself, had been an Underground Railroad operative throughout the 1840s and 50s in Boston, serving in various Vigilance Committees as well as the New England Freedom Association. Smith joined with Senator Charles Sumner and Governor John Andrew "to organize a planning committee and raise the thousands of dollars necessary to commission a prominent sculptor to design and execute the monument." He committed $500 of his own money and became recognized "as the initiator of the evolving commemorative project."[22]

Massachusetts Historical Society

At the dedication of the memorial in 1897, surviving members of the regiment, marched in procession and saluted the monument to their fallen colonel and fellow soldiers. William H. Carney, who had "confiscated" himself decades earlier, joined his fellow veterans in this dedication ceremony.

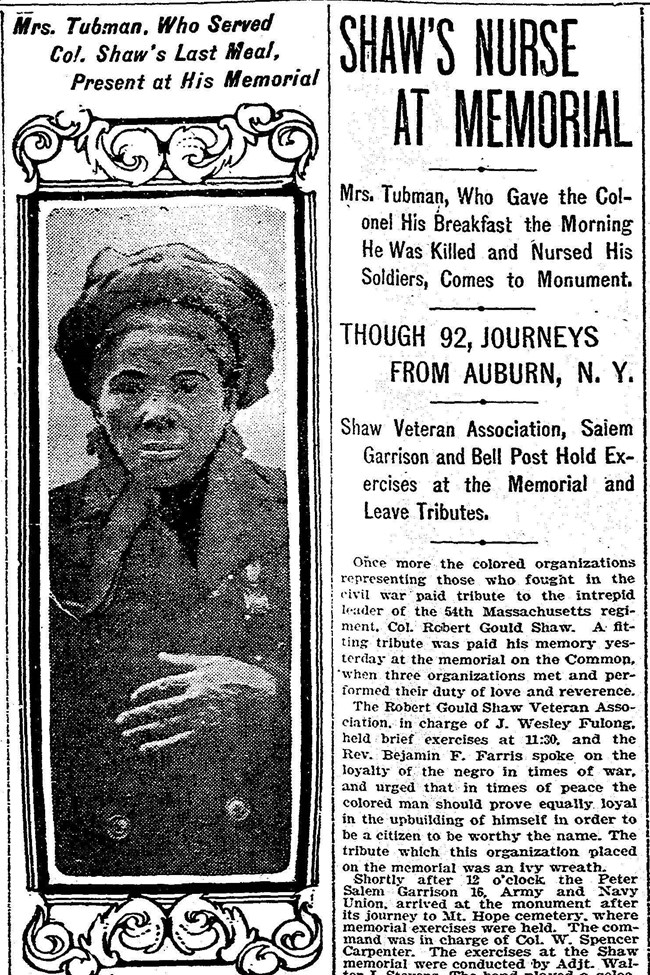

Boston Herald, May 31, 1905

Since its dedication, the memorial has served as a powerful place for the military, particularly Black veteran organizations, to gather and honor its legacy. For example, on Memorial Day in 1905, Underground Railroad leader Harriet Tubman, who had worked with and nursed the wounded of the 54th following Fort Wagner, came from her home in Auburn, New York to participate in a ceremony at the memorial. She told the assembled crowd:

That looks like him [Shaw] the last morning I saw him. He was killed that night. That morning I gave him his last breakfast. This is the first time I have seen the monument close to. I was here when they unveiled it, but the crowd was then so big. I went back to Auburn, but made up my mind to see it again some time.[23]

Speaking at the monument on Memorial Day in 1899, Captain Godfrey Henry Powell, formerly of the Sons of Veterans, captured the importance and meaning of 54th Regiment in his remarks:

The outward and visible sign of the enfranchisement of our race was here given when the fugitive slave, transformed into a soldier under the authority of this grand old commonwealth of Massachusetts, went forth to bear his part in maintaining the union of this glorious republic and to battle for the freedom of the enslaved people of his race.[24]

Though this memorial serves as a testament to the dedication and bravery of the soldiers of the 54th Regiment, it can also remind us of the struggle for freedom for many on the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers and their allies are represented within the regiment, its recruiters, and those who honored their sacrifice with the creation of this memorial. It became a designated site in the National Park Service's National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom in March 2022.

Since its dedication in 1897, the memorial has continued to play an integral role in our ongoing national story, particularly around matters of race, freedom, and justice. To learn more about some ways in which people have used the memorial since its unveiling, please visit The Ongoing March: Commemoration and Activism at the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial.

Footnotes

[1] Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (New York. Penguin Books, 2012), 286-287.

[2] The Freeman, December 19, 1896.

[3] Berkshire County Eagle, March 19, 1863.

[4] David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York. Simon and Shuster, 2018), 391-396.

[5] Martin H. Blatt, “Glory: Hollywood History, Popular Culture, and the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment.” Found in Hope and Glory: Essays on the Legacy of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. Martin Henry Blatt, Thomas J. Brown, Donald Yacovone, eds. (University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst. 2001), 222.

[6] Capt. Luis F. Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment: History of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865 (Bantam Books. New York. 1992. Originally published by the Boston Book Company, 1894), 23.

[7] The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law empowered enslavers and their agents to capture and return freedom seekers to bondage with the full backing of the federal government. It also mandated the assistance of local and state officials and the public at large.

[8] Edwin S. Redkey, “Brave Black Volunteers: A Profile of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment,” in Hope and Glory: Essays on the Legacy of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. Martin Henry Blatt, Thomas J. Brown, Donald Yacovone, eds. (University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst. 2001), 26.

[9] Ibid, 26.

[10] William H. Carney, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (Colored). NARA M1898, accessed via Fold3.com on 2/22/22

[11] Kathryn Grover, The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 253-4

[12] Charles Reason, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (Colored). NARA M1898, accessed via Fold3.com on 2/22/22

[13] Egerton, 153-154

[14] Martha Nicholson McKay, When the Tide Turned in the Civil War (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1929), 40

[15] Egerton, 76.

[16] Redkey, 26.

[17] Thomas Betts, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (Colored). NARA M1898, accessed via Fold3.com on 2/22/22

[18] Egerton, 159.

[19] Reprinted in National Anti-Slavery Standard, May 2, 1863.

[20] National Anti-Slavery Standard, April 30, 1864.

[21] Donald Yacovone, Freedom’s Journey: African American Voices of the Civil War (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2004), 139.

[22] Marilyn Richardson, “Taken From Life: Edward M. Bannister, Edmonia Lewis, and the Memorialization of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment.” Found in Hope and Glory: Essays on the Legacy of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. Martin Henry Blatt, Thomas J. Brown, Donald Yacovone, eds. (University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst. 2001), 95.

[23] Boston Globe, May 31, 1905.

[24] “In Shaw’s Honor” Boston Globe, May 31, 1899, 7.