Part of a series of articles titled The History of Slavery in St. Louis.

Article

Reckoning with Slavery's Legacy in St. Louis

Nick Sacco

Finding a Gateway to the East

St. Louis is nicknamed “the Gateway to the West” thanks to its role as a transportation hub for westward expansion. Thousands of settlers used St. Louis’s steamboats, railroads, and wagon trails as a bridge towards their dreams of financial prosperity in the west. Many enslaved St. Louisans, however, looked towards the east. The Mississippi River was the cultural and political boundary between slavery and freedom. In looking at the river, enslaved people stared at freedom and dreamed of liberation.

The Mississippi River broke some of those dreams. Mary Meachum’s freedom seekers in 1855 were captured near the river and returned to slavery. Pro-slavery residents in Illinois regularly assisted with capturing freedom seekers. And the free steamboat cook Francis McIntosh lost his life to an angry mob after disembarking from the river.

However, the Mississippi also helped some enslaved people realize their freedom dreams. Hiram Reed was a steamboat worker whose enslaver joined the Confederacy when the Civil War broke out. As a punishment to the enslaver, Union General John C. Fremont declared Reed a free man, an act that was reported in the New York Times. Reed later fought for the freedoms of other enslaved people by serving in the Union army himself.

There was no easy path to freedom for St. Louis’s enslaved residents. They traveled in all directions seeking liberation and sometimes went west. But the closest proximity to freedom for enslaved people was just east across the Mississippi River. “The thought of death was nothing frightful to me,” wrote abolitionist William Wells Brown, “with that of being caught, and again carried back into slavery. Nothing but the prospect of enjoying liberty could have induced me to undergo such trials.”

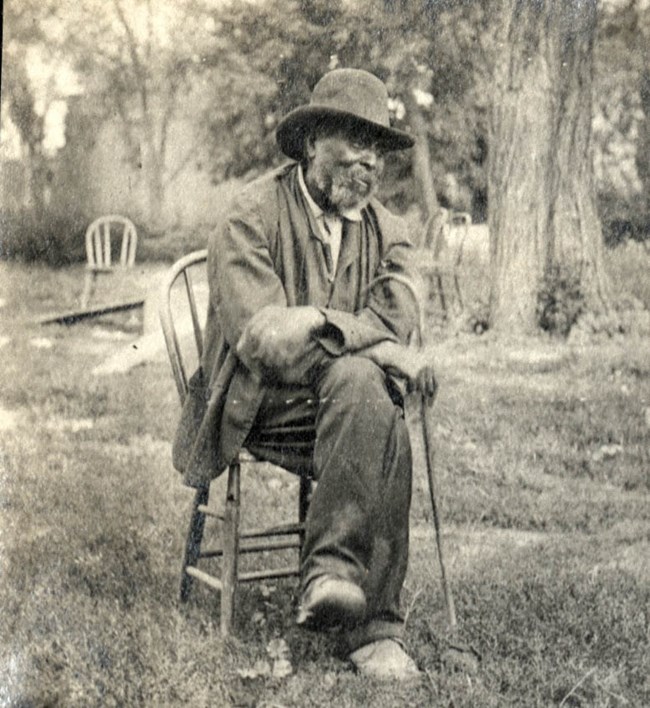

Carolina Hildalgo/St. Louis Public Radio/University of Missouri St. Louis

The Historical Silence of Slavery in St. Louis

St. Louis has chosen to commemorate the lives of local enslavers to a much higher degree compared to enslaved people. Streets and municipalities are named after prominent enslavers such as William Clark, Peter Lindell, Thomas Skinker, William Dorsett, James Jennings, James H. Lucas, and Anne Lucas Hunt. Two local communities and O’Fallon Park are named after John O’Fallon, an enslaver and one of the richest men in St. Louis.

Tangible reminders of slavery’s presence have been torn down because of the painful memories they provoke. Few historical markers exist to commemorate enslaved experiences in St. Louis, creating historical silences within the city’s landscape.

In 1914, the Daughters of the Confederacy funded the erection of a monument at Forest Park to honor the White soldiers who fought for the Confederacy. The monument states that the Confederacy “battled to preserve the independence of the states” without acknowledging why eleven Southern states wanted to leave the Union in the first place. Spurred by protests from residents, the St. Louis city government brokered a deal to have the statue removed in 2017.

In 2012, The Dred Scott Heritage Foundation and the National Park Service funded the erection of a statue depicting Dred and Harriet Scott at the Old Courthouse. It was sculpted by artist Harry Weber and depicts the Scotts facing east towards the Mississippi River. Ten years later, a memorial sculpted by Preston Jackson was dedicated at the St. Louis Civil Courts building, honoring the nearly 300 enslaved people who pursued freedom suits.

Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation Project

Reckoning with Slavery at School and Church

The Catholic church enslaved hundreds of Black St. Louisans. Many who were enslaved by the Jesuits worked at the St. Stanislaus Seminary and farm in Florissant and at Saint Louis University (SLU). At SLU, enslaved people were forced to cook, clean, construct buildings, and farm land north of the campus. Eleven university presidents bought, sold, and rented enslaved people from 1818 to 1865.

Washington University (WashU) also made its fortunes from the exploitation of enslaved Black St. Louisans. When the university was established in 1853, seven of its founding members were enslavers. John O’Fallon, a prominent proslavery businessman, funded the university’s vocational program, the O’Fallon Polytechnic Institute. Recent research has also concluded that primary founder William Greenleaf Eliot did little to challenge slavery and even argued for the colonization of Black Americans to Africa.

These case studies demonstrate how slavery permeated both schools and religious institutions. While not all Christians supported slavery, many White St. Louis Protestants and Catholics alike justified slavery as biblically approved and often benefitted from it.

Today, Saint Louis University (SLU) and Washington University (WashU) are trying to learn more about their complicated histories with slavery. In 2016, SLU collaborated with the Jesuits U.S. Central and Southern Conference to form the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation Project. This project is working with the Descendants of the Saint Louis University Enslaved, who seek to honor and commemorate their enslaved ancestors and work towards reparative justice with SLU. The WashU & Slavery Project is also conducting research to uncover slavery’s legacy in association with WashU.

Washington University in St. Louis

Last updated: November 2, 2023