Last updated: February 26, 2025

Article

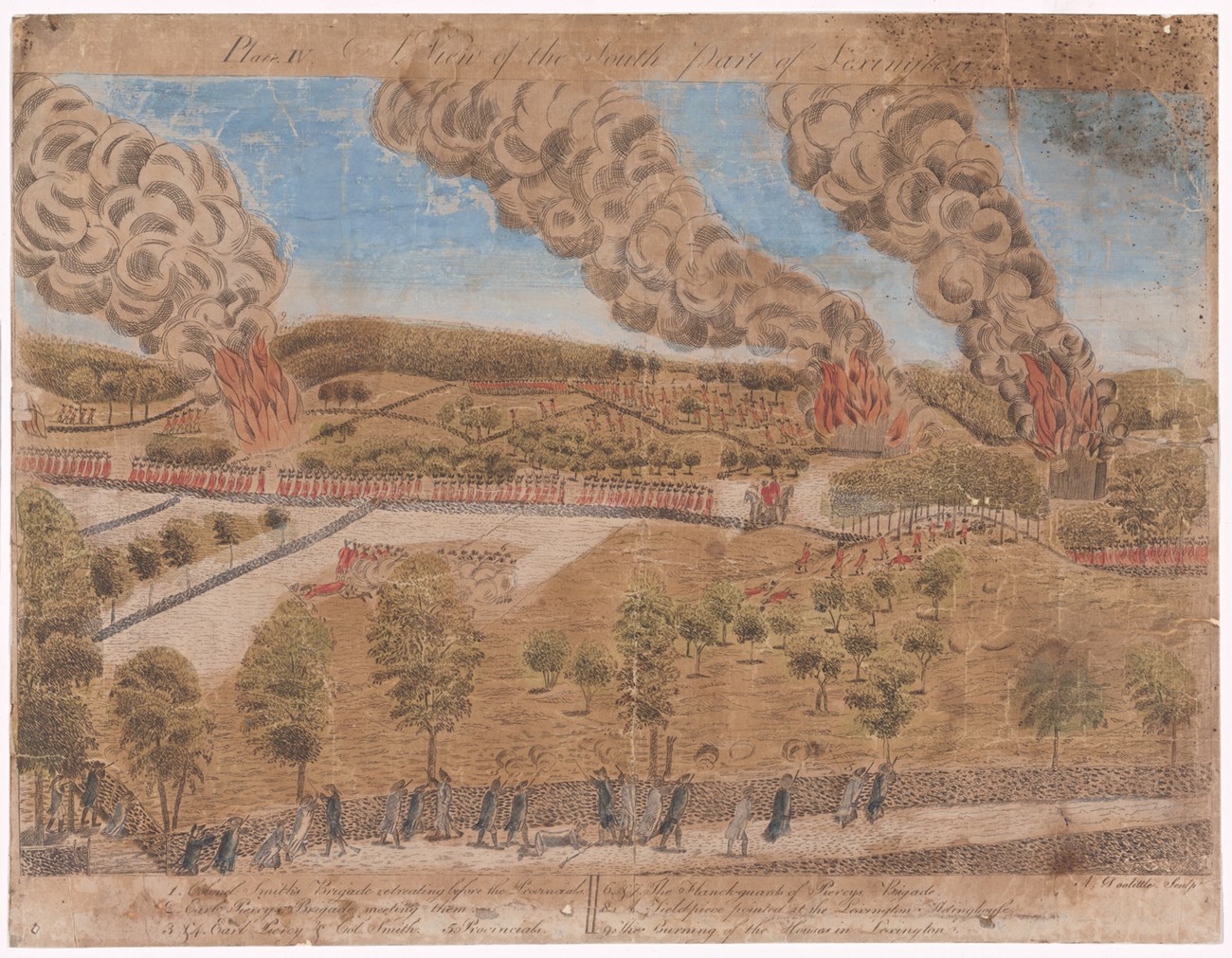

Picturing a Revolution: Printmaking in the American Colonies

From The New York Public Library

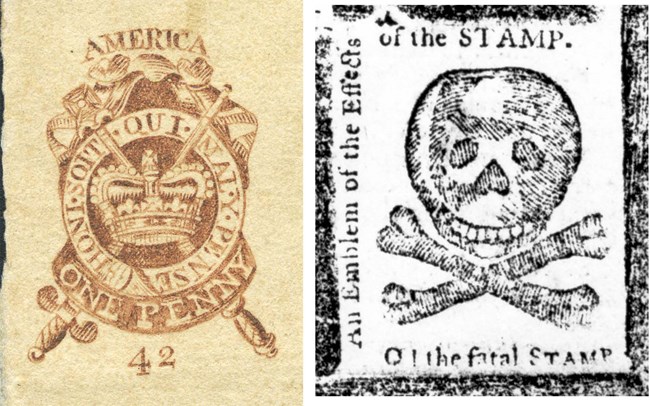

After the French and Indian War, American colonists faced a depressed economy and new tax policies from the British Parliament. Starting with the Stamp Act in 1765 and for the next ten years, opposition spread throughout the thirteen colonies against a series of acts by the British government. Colonists wanted to share ideas, express their discontent, and encourage solidarity against British policies. Creating and distributing images was one way to achieve this.

Printmakers used the printing press to transfer images from a woodcut or a copper plate onto paper. A printer could include a woodcut image alongside the text of a newspaper, almanac, or broadside (poster). Copper-plate images were printed on single sheets of paper. The printing press was the only practical way to make multiple copies of images in the American colonies. People also created printed images on flags. Some images were symbolic, while others depicted actual events. Colonists shared images locally and across great distances.

Smithsonian National Postal Museum (left); From the New York Public Library (right). Click on the image for a link to the New York Public Library.

Some of these early images may seem unpolished, but printmaking was still a developing technology in the American colonies. Silversmiths often served as the first printmakers because they were already skilled in engraving metals.

To oppose the Stamp Act, the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser created its own stamp seal image which other colonial newspapers copied. It mocked the official Parliamentary Stamp Act seal required on taxed paper. Some colonists felt that the tax on paper products, including newspapers, would hurt the economy. Colonists opposed the Stamp Act so vehemently that Parliament repealed it a year later in 1766.

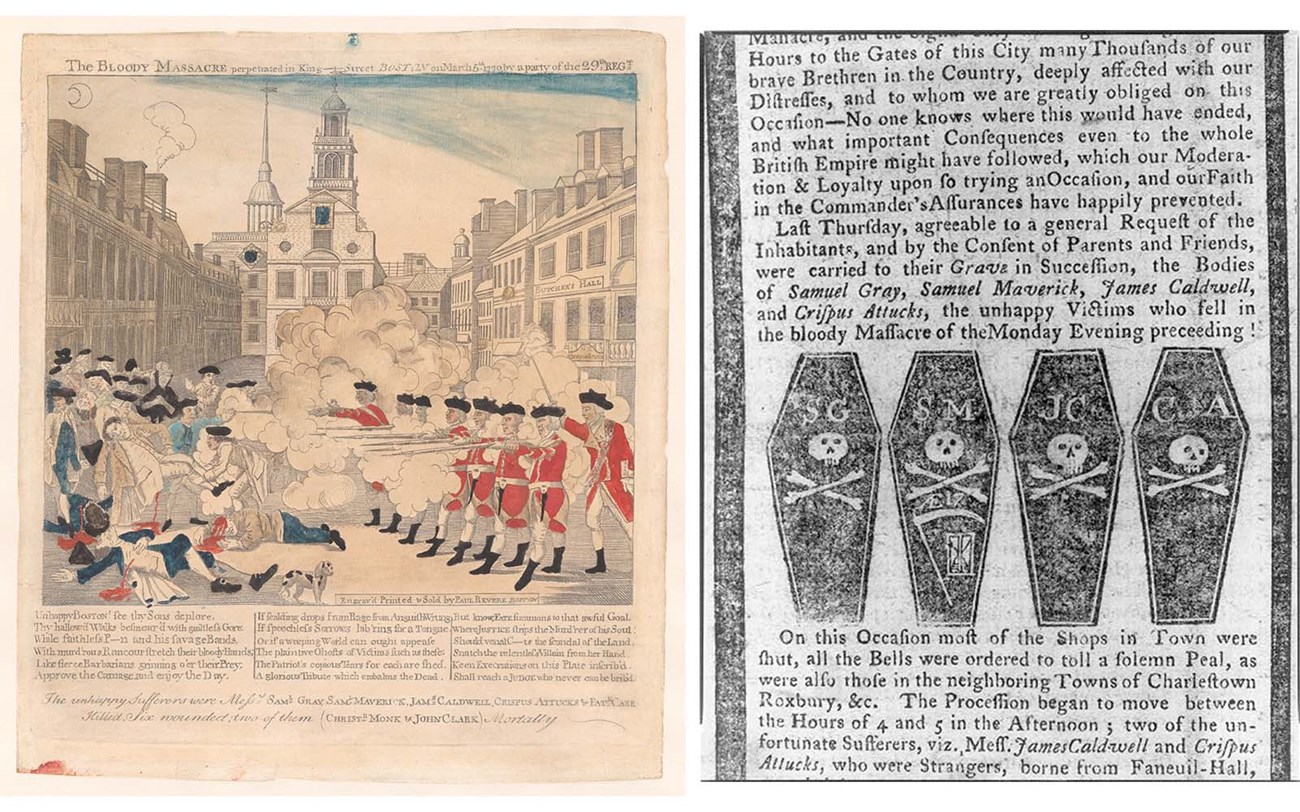

In 1768, British troops arrived in Boston to enforce the Townshend Acts, which for many colonists was as unwanted as the Stamp Act. Animosity over the British military presence exploded in Boston in March of 1770. This event became known as the Boston Massacre. Silversmith Paul Revere created the most memorable and well-known image of the incident. Revere printed 200 copies from his copper-plate engraving and the image was seen throughout the colonies and in London.

Left: The Metropolitan Museum, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910. Right: Library of Congress. Click on the image for a link to the MET's "The Boston Massacre" printing.

Revere also created an image of the coffins of the men killed in the massacre, which accompanied a news report in the Boston-Gazette. Including the initials of the dead men in the image further personalized the tragedy. A fifth person died later, after Revere made this image.

Library of Congress

A tea tax and a tea monopoly granted to the East India Company in 1773 by Parliament extended the crisis in the colonies, especially in Boston. Here, demonstrators dumped detested tea in Boston Harbor in December of 1773 at the Boston Tea Party.

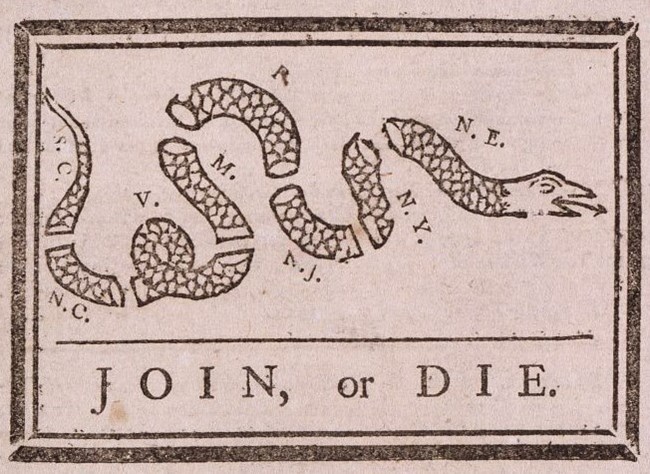

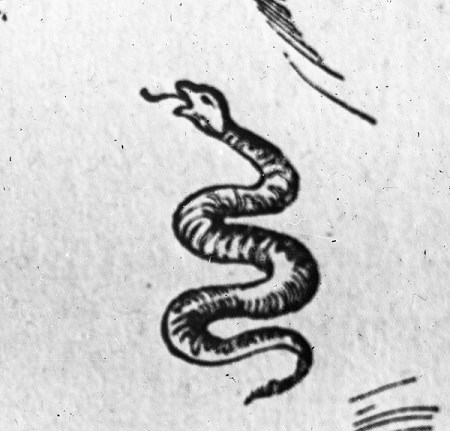

In the aftermath of the Boston Tea Party, Parliament imposed severe restrictions on the people of Massachusetts with the Intolerable Acts (or Coercive Acts) in 1774. These Acts caused general unrest and led to the revival of a symbolic image from 1754 created by Benjamin Franklin. Franklin designed this woodcut (right) to encourage British colonial solidarity in opposing the French in the French and Indian War.

Colonists understood the favorable biblical and mythological references to snakes that Franklin was making with this image. Franklin launched the rattlesnake as a symbol of the American colonies in these early years.

Library of Congress.

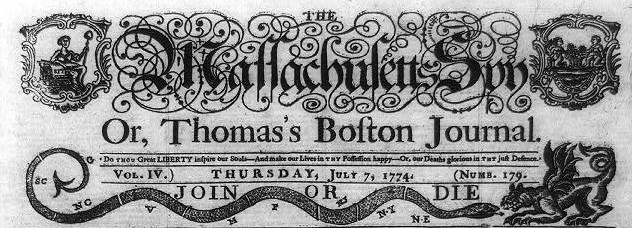

The words "Join or Die" or "Unite or Die" accompanied by a snake image were calls to solidarity that became part of newspaper mastheads in Boston, New York and Philadelphia through the year 1775, part of the continuing opposition to the Intolerable Acts. For example, the Massachusetts Spy or Thomas Boston's Journal frequently printed this image beneath its masthead, beginning in 1774.

The Metropolitan Museum, New York.

With the confrontation at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, political resistance escalated into military action. A militiaman and silversmith from Connecticut, Amos Doolittle, created his images of the battle (see top of article) based on interviews he conducted within days of the battle in Lexington and Concord. He engraved the action on copper plates and sold prints to the public.

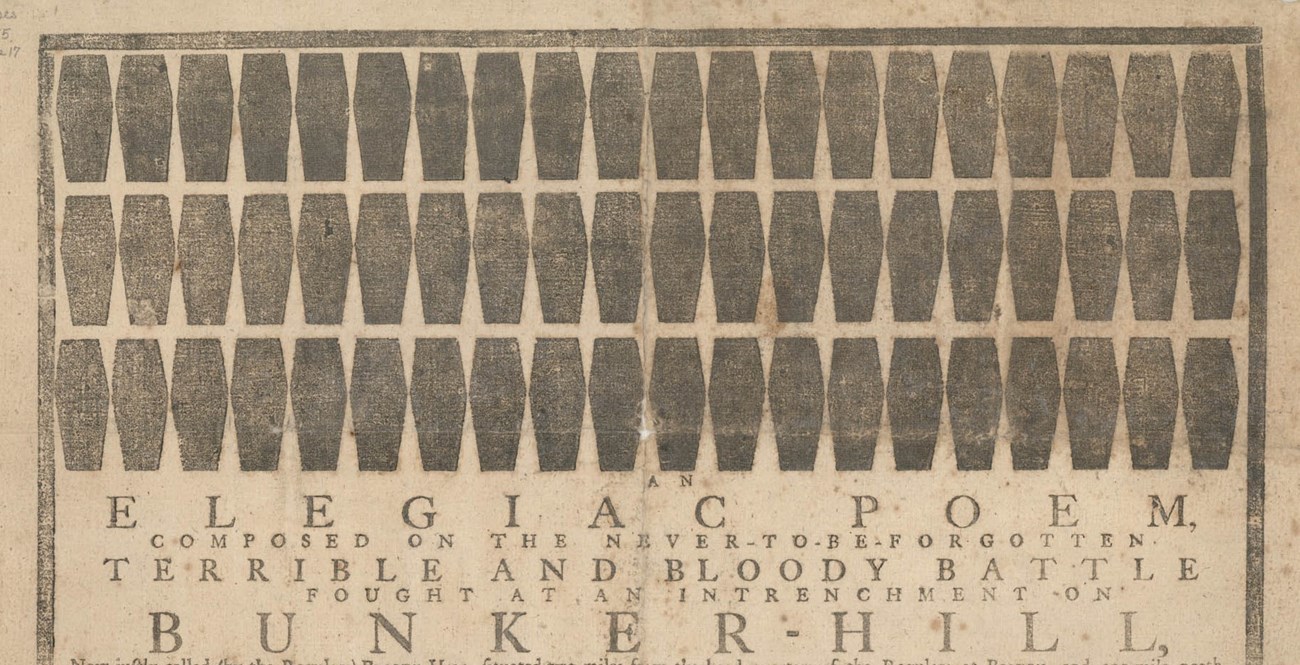

Within a few months of the fighting at Lexington and Concord, provincial and British forces met again, this time at Bunker Hill in Charlestown near Boston.

Bernard Romans witnessed the battle and created this engraving (left) soon after the battle. He printed it and sold copies in Philadelphia.

Massachusetts Historical Society.

Over 100 provincial militiamen died in the Battle of Bunker Hill and printer Ezekiel Russell of Salem, Massachusetts wanted to highlight that fact with these coffin images in his broadside (above), printed within days of the battle.

Thomas Crane Public Library

Franklin's rattlesnake imagery, this time ominously coiled (right) was used often as a symbol of colonial hostility against British polices. Most enduring was the flag designed by South Carolinian leader Christopher Gadsden for the colonial navy in 1775 with the words "Don't Tread on Me."

American colonists faced economic, political, and military challenges in the years 1765-1775 and some colonists wanted to share their ideas, express their discontent, and encourage solidarity both locally and across distances. Creating and distributing images was one of the methods they used. Some image motifs like coffins, rattlesnakes, and billowing smoke were likely very effective since printmakers used them repeatedly.

Vast communication networks and the printing press allowed these depictions of the revolution and opposition to British policies to circulate throughout the colonies more than ever before. American colonists saw these images in newspapers, broadsides, individual sheets, and on flags. These images, serving as propaganda, likely helped garner support for the revolutionary cause.

Sources

- American Revolution Institute. "Imaging the Battle of Bunker Hill." https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/imagining-the-battle-of-bunker-hill/.

- Charles Harper Walsh, The Earliest Copper Engraving Executed in the American Colonies, vol. 15 (Washington, D.C.: Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 1912), 54-72.

- Clarence S. Brigham, Paul Revere's Engravings (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1954).

- Daniel P. Stone. "Join or Die: Political and Religious Controversy Over Franklin’s Snake Cartoon." January 10, 2018. https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/01/join-die-political-religious-controversy-franklins-snake-cartoon.

- Elizabeth L. Roark, Artists of Colonial America (Artists of an Era) (Westport, CT and London: Greenwood Press, 2003)

- Massachusetts Historical Society. "An Elegiac Poem, Composed on The Never-To-Be-Forgotten Terrible and Bloody Battle Fought at An Intrenchment On Bunker-Hill." https://www.masshist.org/database/785.

- New England Historical Society. "Amos Doolittle Creates the First (and Only) Accurate Engravings of the Battles of Lexington and Concord." https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/amos-doolittle-connecticuts-paul-revere.

- Nicolas Lampert, A People's Art History of the US (New York: The New Press, 2013).

- Revolutionary War and Beyond. "Gadsden Flag." October 23, 2011. Revolutionary War and Beyond. https://www.revolutionary-war-and-beyond.com/gadsden-flag.html.

- Wendy J. Shadwell, American Printmaking: The First 150 Years (New York: Museum of Graphic Art, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1969).