Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

Britain Begins Taxing the Colonies: The Sugar & Stamp Acts

"...The English government cannot long act towards a part of its dominions diametrically opposed to its own, without losing itself in the slavery it would impose upon the colonies."—New York Gazette, June 6, 1765, reprinted in Boston Evening Post, June 24, 1765[1]

Smithsonian Institution

Harbottle Dorr, a North End ironmonger [seller of hardware, tools, and household implements], began collecting and annotating Boston newspapers in January 1765. Offering his opinions as a man of middling rank toward the Revolutionary struggle for liberty, he claimed that the June 6 New York Gazette article "first gave the Alarm about the Stamp Act."[2]

Parliament passed the Stamp Act on March 22, 1765, to pay down a national debt approaching £140,000,000 after defeating France in the Seven Years War (1763). A year earlier, Parliament passed the Sugar Act, their first revenue-raising measure. Both taxes promised dire consequences in a post-war economy. While the Sugar Act was a duty only on foreign goods, the Stamp Act taxed items within the colonies. Previously, only colonial assemblies assumed responsibility for internal taxes.[3]

Beginning November 1, 1765, legal documents, academic degrees, appointments to office, newspapers, pamphlets, playing cards, and dice required embossing with a Treasury stamp as proof of payment of the tax.[4] Colonial essayists, orators, and ordinary people responded with cries of "slavery," "tyranny," and "No taxation without representation."

Archives and Collections at Amherst College

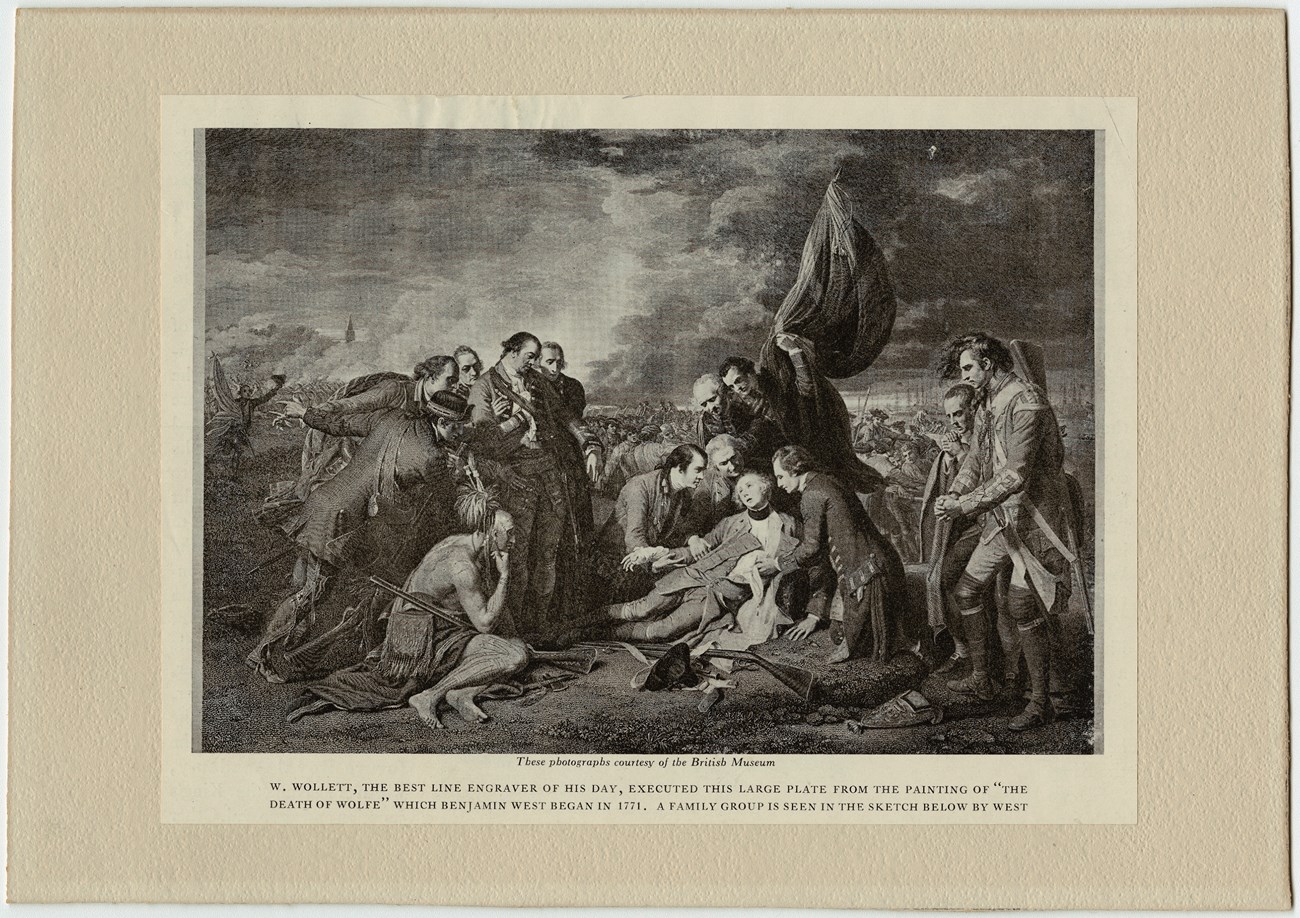

The same angry colonists who now attacked British taxation policies had proudly celebrated their country's victories in the Seven Years War a few years earlier. On October 16, 1759, Bostonians celebrated Britain's defeat of France in the Plains of Abraham battle in Quebec. Printer John Boyle noted: "…the Regiment of Militia were mustered, and the Town beautifully illuminated in the Evening." On September 26, 1760, "public rejoicing" accompanied news of Montreal's surrender. Finally, on May 24, 1763, Boyle declared Britain's complete victory: "The Definitive Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the King of Great Britain, the French and Spanish Kings was sign'd at Paris February 10, 1763."[5]

Massachusetts colonists remained especially proud since thousands of their provincial soldiers served—and died—alongside British "regulars" in the New York and Canadian theaters of war. Among them was 21-year-old silversmith Paul Revere, who enlisted as a Second Lieutenant in Richard Gridley's Artillery Train on February 18, 1756. French victories cancelled Revere's participation in a British plan to seize a French fort at Crown Point on Lake Champlain, New York, and he returned home in November 1756.[6]

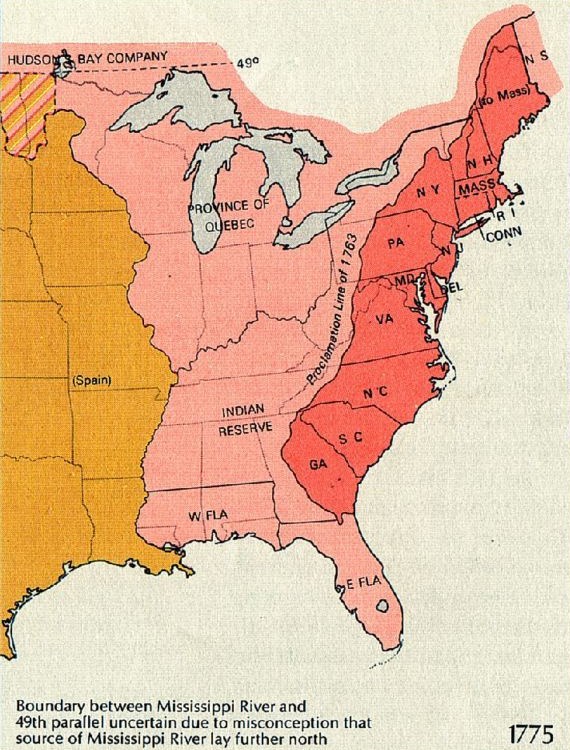

Under the peace treaty Britain gained vast new territory, including French Canada and French territory east of the Mississippi. How would Britain pay down its war debt and the additional expense of defending its enlarged North American empire? How would American colonists respond to Britain’s policies?[7]

Peace ended colonial contracts to supply the British military with weapons, uniforms, and provisions as well as the steady supply of gold and silver that paid for those goods. After 1760, British merchants began tightening up credit to colonial merchants. Britain’s slowing economy led to a slumping West Indian economy, which reduced demand for New England livestock, lumber, and fish. Merchants in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia declared bankruptcy in alarming numbers.[8]

Artisans and laborers faced lower income and higher costs of food, firewood, and taxes.[9] On February 26, 1764, John Boyle wrote about another crisis—smallpox: "…'tis feared by many that it will be impractible [impractical] to prevent its spreading thro’ the Town."[10] Paul Revere's family was one of seven afflicted families in Boston's North End. Though his family survived, Revere's income from his previously thriving silver shop dropped from £102 in 1764 to £60 in 1765.[11]

To make matters worse, Britain began imposing taxes, leading to more economic distress—and political danger. On May 15, 1764, the Boston Town Meeting asked their representatives to the Massachusetts General Court [Legislature] to

use your power and influence in maintaining the invaluable Rights and Privileges of the Province…For if our Trade may be taxed why not our Lands? Why not the produce of our Lands, and every Thing we possess or make use of?....If Taxes are laid upon us in any shape without ever having a Legal Representative where they are laid, are we not reduced from the Character of Free Subjects to the miserable state of tributary Slaves…[12]

Christ Church, University of Oxford

British officials saw the situation differently. When George Grenville became Prime Minister in April 1763, he grappled with the national debt, a debt that included an annual estimated cost of £200,000 for 10,000 soldiers in America recommended by his predecessor Lord Bute. The outbreak of Pontiac's Rebellion, a major American Indian uprising in the Ohio country in May 1763, increased the urgency to maintain a military force in America.[13]

During the war, Britons at home bore a heavy tax burden. In contrast, the Crown requisitioned colonial assemblies for soldiers and supplies but could not force compliance, and reimbursed as much as two-fifths of the expenses. It seemed reasonable that the colonies should contribute to their own defense, especially since the Board of Trade estimated that the American colonies annually smuggled approximately £700,000 of merchandise. It also seemed logical to examine existing trade laws as a starting point for new taxes.[14]

In 1651 Britain passed its first Navigation Act and continued to update trade acts as needed. However, the goal was not to raise revenue but to impose a high enough duty on foreign trade to channel trade between Britain and her colonies.[15] Grenville's proposed duties would raise revenue and be strictly enforced, reducing the colonists' ability to evade duties.

He began by revising the Molasses Act of 1733, due to expire in December 1763. Enacted on April 5, 1764, to take effect on September 29, the new Sugar Act cut the duty on foreign molasses from 6 to 3 pence per gallon, retained a high duty on foreign refined sugar, and prohibited the importation of all foreign rum. This part of the act affected New England, where distilling sugar and molasses into rum was a major industry.[16] The Sugar Act also taxed numerous foreign products, including wine, coffee, and textiles, and banned the direct shipment of several important commodities such as lumber to Europe, upsetting the balance of trade for merchants in Northern seaports. Passage of the Currency Act on April 19, 1764 (effective September 1, 1764) banned colonial paper currency, requiring the Sugar Act to be paid in gold and silver.[17]

More than half of the articles in the Sugar Act dealt with enforcement. It required Customs collectors to report to their colonial posts, instead of appointing underlings who were susceptible to bribery. Masters of vessels had to post a bond and carry affidavits attesting to the legality of their cargo. At every stop in their voyage officials examined their paperwork, assisted in their efforts by the Royal Navy. Those caught with illegal cargo were no longer tried by a sympathetic local jury but at a new vice-admiralty court in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[18]

On January 14, 1765, the Boston Evening Post printed a letter from London, dated October 20, 1764, about the new trade regulations: "….every cargo of the American product is deemed prohibited goods….if, therefore, this traffic is prohibited, the colonies must be ruined…."[19]

Their ruin was not complete. In the summer of 1764, James Otis, Boston attorney and representative to the Massachusetts General Court, responded to the Sugar Act with The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved. After promising colonial obedience to King and Parliament, Otis emphatically upheld an essential right of all English citizens: "Taxes are not to be laid on the people, but by their consent in person, or by deputation…." On February 8, 1765, Arthur Savage, writing from London, informed his brother, merchant Samuel Phillips Savage, that the Stamp Act had passed "by a great majority." Otis's argument "has not been of any service."[20]

The struggle for liberty was just beginning.

Footnotes

[1] In Harbottle Dorr Collection of Annotated Massachusetts Newspapers, 1765-1776, Vol. I, pp. 111, 114, https://www.masshist.org/dorr/.

[2] Jayne E. Triber, A True Republican: The Life of Paul Revere (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998), 41-42.

[3] Ed., Jack P. Greene, Colonies to Nation, 1763-1789: A Documentary History of the American Revolution (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975), 12-44; Edmund S. And Helen M. Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (New York and London: Collier Macmillan, 1963), Chapter Five; I. R. Christie, Crisis of Empire: Great Britain and the American Colonies, 1754-1783 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1966), Chapter 3.

[4] Text of Stamp Act: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/stamp_act_1765.asp

[5] Boyle’s Journal of Occurrences in Boston, 1759-1788, New England Historical and Genealogical Register Vol. 84 (April 1930), 148-149 (on Quebec and Montreal), 162 (on peace); Derek McKay and H. M. Scott, The Rise of the Great Powers, 1648-1815 (London and New York: Longman, 1983), 192-200; Christie, Crisis of Empire, Chapter Two.

[6] Revere’s reminiscences of military service, fragment, second copy, April 27, 1816, Roll 3, Revere Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS); Triber, A True Republican, 21-25; Fred Anderson, A People’s Army: Massachusetts Soldiers and Society in the Seven Years’ War (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 1-12, 26-39, 168-180.

[7] McKay and Scott, The Rise of the Great Powers, pp. 197-200; Greene, Colonies to Nation, 12-14; Lawrence Henry Gipson, The Coming of the American Revolution, 1763-1775 (New York: Harper and Row, 1954), 55-57.

[8] Marc Egnal, A Mighty Empire: The Origins of the American Revolution (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1988), 126-135; Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1979), 246-250.

[9] Nash, Urban Crucible, 250-263.

[10] Boyle’s Journal of Occurrences, 84, 164.

[11] On the smallpox epidemic, see Christian Di Spigna, Founding Martyr: The Life and Death of Dr. Joseph Warren, the American Revolution’s Lost Hero (New York: Broadway Books, 2018), 62-66. Revere’s income, in Waste Book and Memoranda, Vol. I, Roll 5, Revere Family Papers, MHS. See also, Triber, A True Republican, 37-41.

[12] Ed., William H. Whitmore, Report of the Record Commissioners of Boston, Boston Town Records, 1758-1769 (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1886), 119-122 (quotes on p. 120, 121-122).

[13] Christie, Crisis of Empire, 39-46; John L. Bullion, “Security and Economy: The Bute Administration’s Plans for the American Army and Revenue, 1762-1763, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., 45 (July 1988), 499-504.

[14] For at least two decades before Grenville’s tax plan, Board of Trade records document colonial smuggling. See Christie, Crisis of Empire, 31-32, 39-46; Gipson, Coming of the American Revolution, 55-59; Thomas C. Barrow, “Background to the Grenville Program, 1757-1763,” William and Mary Quarterly, V. 22, No. 1 (Jan. 1965), 93-104 (p. 95 on 1759 trade investigation); Don Cook, The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies, 1760-1785 (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1995), 58.

[15] Gipson, Coming of the American Revolution, 22-27.

[16] Christie, Crisis of Empire, 46-48; Gipson, Coming of the American Revolution, 55-59. On the role of rum in the New England slave trade, see Jared Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England (Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019), 26-28, and “The Slave Trade,” Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS), African Americans and the End of Slavery.

[17] For full text of the Sugar Act, see https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/sugar_act_1764.asp. For more on the Sugar and Currency Acts, see Greene, Colonies to Nation,12-16, 25-26; Christie, Crisis of Empire, 46-48; Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, Chapter 3.

[18] Text of Sugar Act, relating to enforcement, starting with Article XX, in https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/sugar_act_1764.asp. See also, Greene, Colonies to Nation, 12-16; Christie, Crisis of Empire, 48-49; Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 39-41.

[19] Harbottle Dorr Collection, Vol. I, p.5, https://www.masshist.org/dorr/.

[20] Otis, The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved, in Greene, Colonies to Nation, 28-33; Arthur Savage, Jr., to Samuel Phillips Savage, February 8, 1765, S. P. Savage II Papers, MHS; Triber, A True Republican, 39-40.