Last updated: March 6, 2023

Article

The People of Fiske Hill

Although Dr. Joseph Fiske, a cousin, visited the house over the next few days to care for the wounded soldiers, Benjamin later buried two of them on the property. The Fiske family passed down these events as oral tradition until Rebecca’s testimony was written down in the 1827 edition of the Harvard Register. And yet, there’s little we really know about the Fiske family besides this one noteworthy encounter.

Concord Road, now known as Massachusetts Avenue, was an important corridor connecting Concord to Lexington and eventually to the waterfront. The farmsteads of Fiske Hill were positioned along this turnpike route, proving advantageous for transporting agricultural and dairy products, like meat, vegetables, cider, and hides, to the Boston market.

The 1775 property boundaries of Fiske Hill were derived from deeds, probate records, and the remains of stone walls, encircling a 0.5-acre home lot that included a house, barn, stockyard, cow yard, hog house, enclosed garden, corn shed, and three wells. Today, the house foundation is long gone, as are the stone wall boundaries. All that remains today is a cellarhole, which now marks the Ebenezer Fiske house.

Several construction projects over the years destroyed the original Ebenezer Fiske house. Multiple studies conclude several different locations for the house, but archeologists reconstructed the house boundaries to verify that the Fiske lot included the cellarhole. Strong evidence confirms the cellarhole to be accurately designated as Ebenezer’s house.

Seventeenth-century New England experienced a period of a steadily increasing English population. By the 1650s, a few large farmsteads developed in present-day Lexington, then known as Cambridge Farms. The town of Lexington was established in 1713 along the perimeter of the Boston core area. Like its neighbors, Concord (1635) and Lincoln (1754), Lexington’s economic base remained primarily agricultural, with an emphasis on grains like corn, wheat, rye, and barley. Flax and hemp were grown for use in local linen textile production. Orchards yielded apples that produced large amounts of cider consumed in households and taverns.

Residents supported local craftspeople more by purchasing domestic redwares, wearing footwear, garments, and printed calico manufactured in small workshops, drinking out of free-blown glass bottles, and building their homes with handwrought nails.

The Fiske Family

The Fiske farmstead on Fiske Hill was owned by five successive generations of the family. David Fiske II, Ebenezer’s grandfather, was born in England in 1624 and came to the New World around 1636 with his father, David I. David II likely inherited his original 16-acre tract of land on Fiske Hill as a dowry from his first wife's stepfather, Deacon Gregory Stone, sometime between his marriage in 1647 and his first wife's death in 1654.

David Fiske II, also known as Lt. Fiske, established an early farmstead with a house, barn, and outbuildings on the east side of Fiske Hill. Lt. Fiske purchased a 20-acre parcel from Samuel Stone in 1664. By 1684, he had approximately 68 acres. His son, David Fiske III, purchased another farmstead in 1712 that was located across the county road from his father’s property. Three years later, David III gave this farmstead to his youngest son, Ebenezer Fiske, when he was twenty-three years old. Ebenezer occupied this property until 1729, when he inherited his father’s farmstead.

The terms of Ebenezer’s inheritance stated that he receives his father's farmstead property with the proviso that he cares for his mother and father for the duration of their lives. As it turned out, both parents died within a few months, so Ebenezer sold his land across the road and permanently settled into his father's farmstead.

Ebenezer Fiske died on December 19, 1775, not long after the fighting along the Bay Road. Since Ebenezer's wife, Bethia, had predeceased him, his 69-acre property on Fiske Hill, including the seventeenth-century house built by David Fiske III, was left to Benjamin and Rebecca. Benjamin died in 1785, so Rebecca administered the entire Fiske estate until Benjamin II turned 21 in 1799.

After Rebecca's death in 1847, her widow rights were sold to the heirs of Robert Parker for a nominal $100.00, thus ending nearly 200 years of Fiske family ownership in Lexington.Upon Ebenezer’s death, it was said that he owned one of the largest and most prosperous farms in Lexington. It is possible that Ebenezer enlarged the original house for use as an inn, removing the original 10 ft lean-to and replacing it with an 18 sq ft addition with a full cellar. This house would have been grander and newer than his neighbors’, earning the title of "mansion house."

Three Fiske houses have been located on Fiske Hill. First was Lt. David Fiske II's house that was built around 1655. Next came David Fiske III's house, later referred to as the Ebenezer Fiske house, that was built around 1667 and occupied by Ebenezer from 1729 to 1775. Last was the Jonathan Fiske homestead, originally inhabited by Ebenezer’s brother, which Ebenezer owned from 1715 until 1729 when he inherited his father’s property.

Archeological Findings

Excavations yielded a significant assemblage of 4,978 seventeenth- and eighteenth-century artifacts, forming the largest collection of material of this type from any site within the park. Archeologists identified an outbuilding, a trash pit, post molds, three wells, and a possible fence line marked with pebbles.

Archeologists also came across a 1798 penny and 40 clay marbles in this area. Built into the foundation was a box-like arrangement containing a large quantity of broken redware, earthenware, late square cut nails, animal bones, and several fragments of clay pipes. Eight of these fragments are part of pipes labeled “T.D.”

Ebenezer was in his sixties by the time Dormer started manufacturing his signature pipes. As an older man with grown children to care for him and his farm, he probably had plenty of free time to sit back and relax with his pipe. A respected landowner, proprietor of a “mansion house,” and influential member of a well-known and established lineage in his small, rural community, Ebenezer had the means to purchase status symbols like imported pipes from a popular and reputable maker. Given the large quantity of broken pipe pieces, it is likely Ebenezer or other members of the family enjoyed smoking frequently.

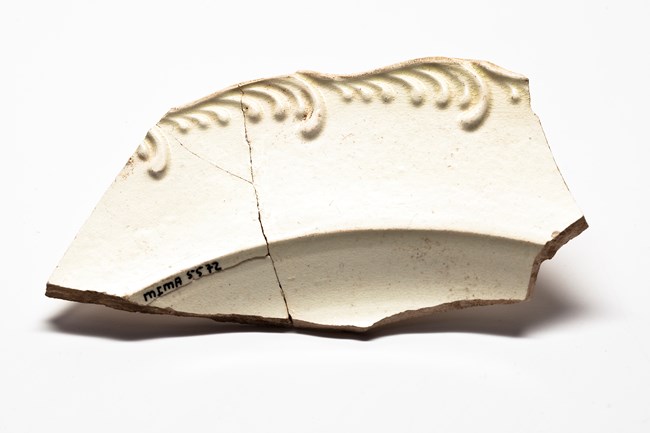

Ebenezer was not the only one who left his imprint on the house. Rebecca administered the estate for fourteen years and made several improvements to the property during that time, as evident in the estate inventories as well as her own personal account book. She continued to live in the house while she retained partial ownership and could have also overseen the purchasing of tableware or other ceramics for the household. In the same parlor where Ebenezer once smoked tobacco, Rebecca might have stored or used the creamware, stoneware, and pearlware vessels that were since recovered from the house foundation.

The documentary record describes the layout of the Ebenezer Fiske house in some detail, making it possible to reconstruct the location of certain features and to detect some evidence of any remaining structures. However, only archeology can uncover the kinds of ceramics the Fiskes purchased or the pipes they smoked. This farmstead complex evolved to become a multigenerational, continuously occupied family compound, revealing the material culture of the Fiske family and the people they enslaved.

Sources

Herbster, Holly and Steven R. Pendery2005 Archaeological Overview and Assessment: Minute Man National Historical Park. Northeast Region Archeology Program, National Park Service.

Pierce, Frederick Clifton

1896 Fiske and Fiske Family: being the record of the descendants of Symond Fiske, lord of the manor of Stadhaugh, Suffolk County England, from the time of Henry IV to date, including all the American members of the family. Chicago.

Towle, Linda A. and Darcie A. MacMahon

1987 Archeological Collections Management at Minute Man National Historical Park, Massachusetts. Volumes 1-4. ACMP Series No. 4. Division of Cultural Resources, National Park Service. Boston, Massachusetts.

Walker, Iain C.

1966 TD Pipes – A Preliminary Study. Quarterly Bulletin of the Archaeology Society of Virginia, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 86-102.