Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 16, No. 2, Fall 2024.

Article

Paleontology and Geology of John Boyd Thacher State Park National Natural Landmark

Article by Justin Tweet, NPS Paleontology Program

for Park Paleontology Newsletter, Fall 2024

NPS photo.

The fossils that tend to be most familiar to people are from large vertebrates: dinosaurs, mammoths, saber-toothed cats, megalodon, and others. Other kinds of fossils are just as scientifically important, if not more. Marine invertebrates such as corals and brachiopods (“lamp shells”) can tell us things that big vertebrates cannot, because they are found in greater numbers and their fossils are more complete. Patterns of evolution, divisions of geologic time, depositional environments, the ancient positions and travels of continents, and other areas of study all owe a great deal to centuries of study of these fossils. John Boyd Thacher State Park in eastern New York is a historic location for the study of marine invertebrate fossils and the rocks containing them. Because of these rocks and fossils, the park has recently been recognized as a National Natural Landmark (NNL).

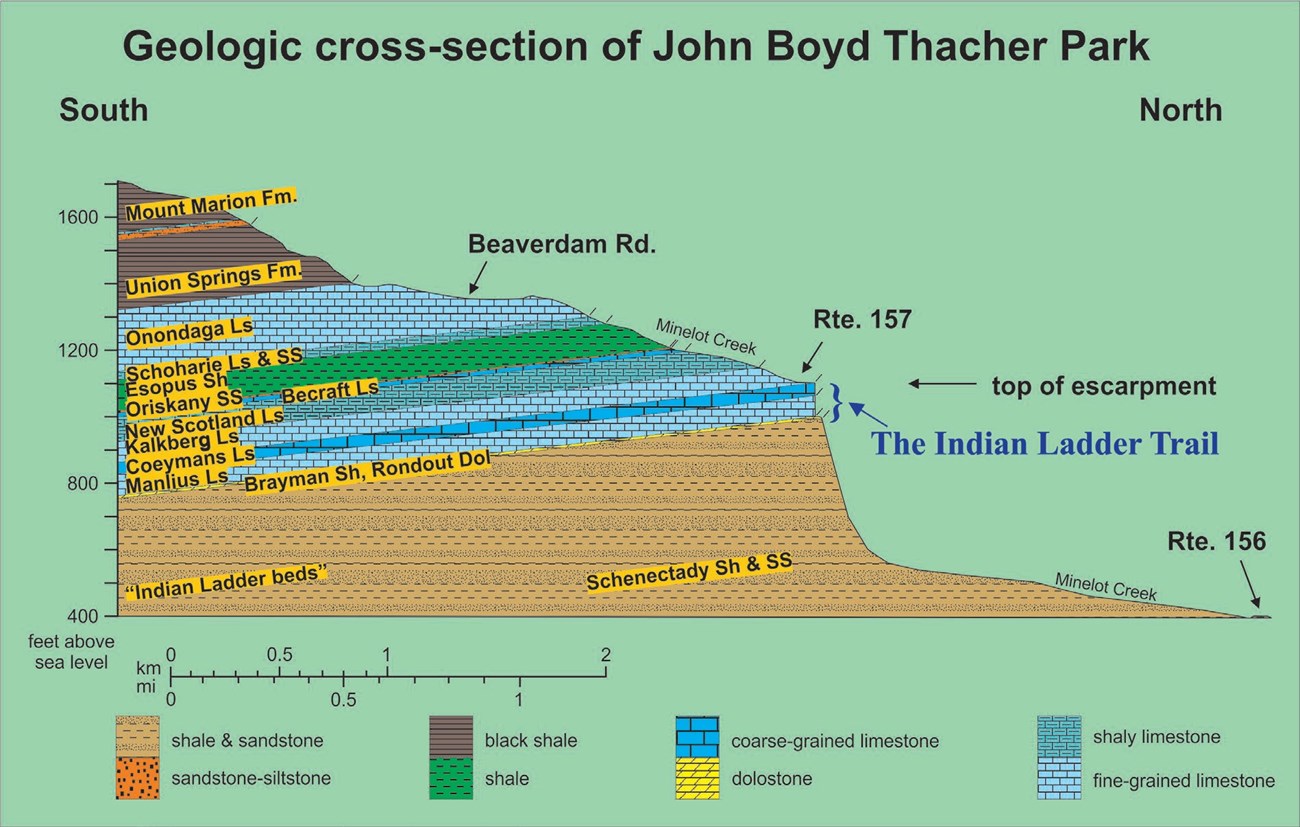

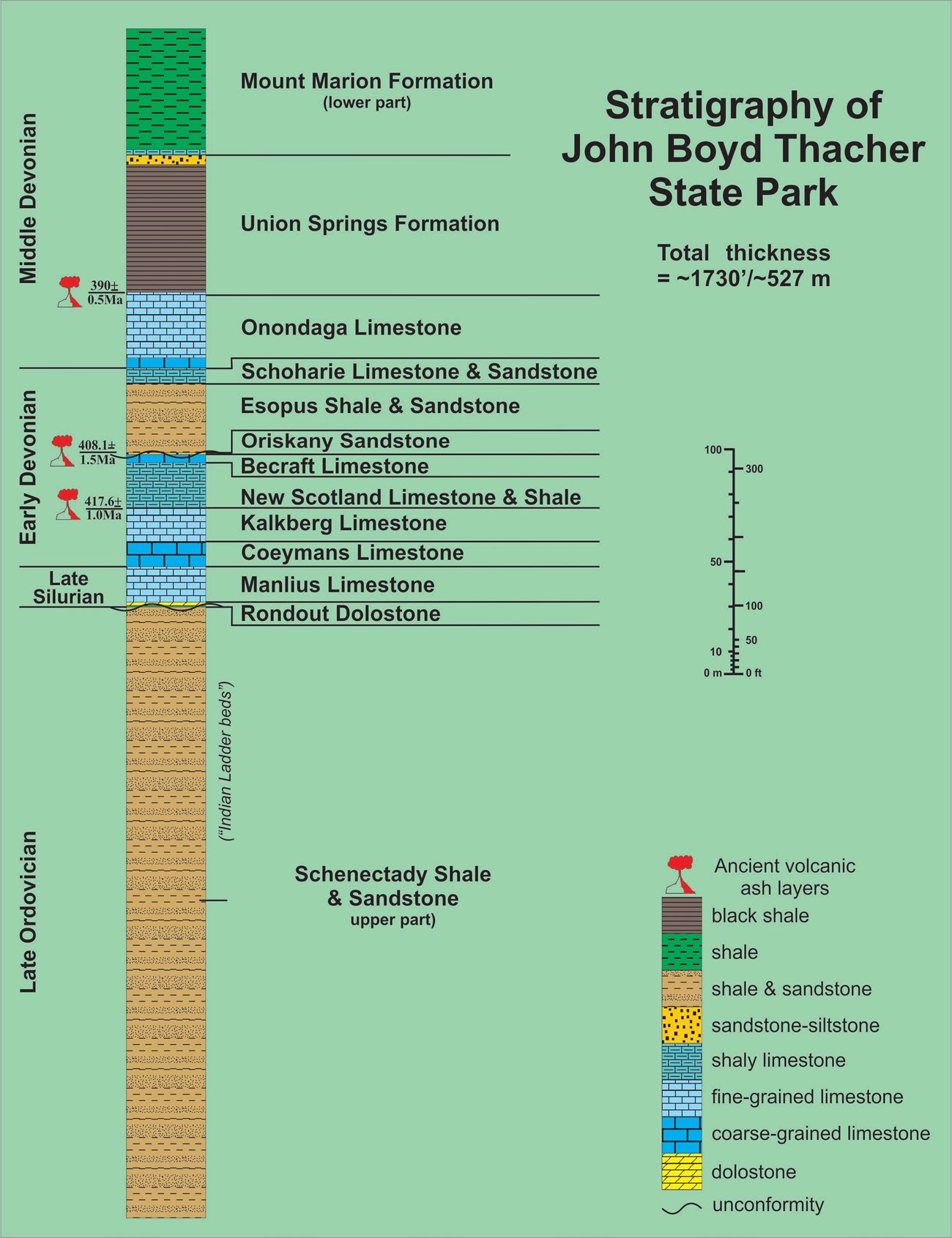

John Boyd Thacher State Park protects part of the Helderberg Escarpment, which rises sharply over a short distance. Definitions of the escarpment differ, but within the park there is a rise of 384 meters (1,260 feet) over a little less than 5 kilometers (3 miles), including bare rock cliffs. The escarpment is part of the steep side of a cuesta, a topographic feature consisting of a steep rise on one side and a gentle slope on the other. Elevation continues to rise at the park for a few miles going west and south, but not as steeply. The steep side of the cuesta here exposes strata from more than a dozen Middle Paleozoic formations, from the Late Ordovician-age Schenectady Formation at the base to the Middle Devonian-age Mount Marion Formation at the top. Geologists and paleontologists realized the scientific value of the exposures here early in the 19th century, making the future John Boyd Thacher State Park a key site for study.

Image courtesy of Charles Ver Straeten (New York State Museum), from Venti et al. (2021).

NPS photo.

Image courtesy of Charles Ver Straeten (New York State Museum), from Venti et al. (2021).

Fossils can be readily seen in almost all of the formations at John Boyd Thacher State Park and are often abundant and well-preserved. The lowest units, below the level of the sharp cliff face, are not well-exposed and are sparsely fossiliferous. The cliff face, about 100 ft (30 m) tall, is primarily made of the late Silurian-age Manlius Limestone and the overlying Early Devonian-age Coeymans Limestone. The Manlius Limestone has fossils indicating an extremely salty nearshore tidal setting, such as microbial structures, layered stromatoporoid sponges, and ostracods (“seed shrimp”). The Coeymans Limestone was deposited in deeper water (but still very shallow compared to an open ocean) and has abundant fossils of a small number of species, including a few brachiopod species and crinoids (“sea lilies”) and less abundant corals. Beyond the cliff level are several less durable formations with various corals, bryozoans (“moss animals”), brachiopods, cephalopods, snails, trilobites, and crinoids, capped by a less prominent second cliff formed by the Middle Devonian Onondaga Limestone. A couple of poorly exposed Middle Devonian shaly units make up the top of the park’s stratigraphic section.

NPS photo.

NPS photo.

Visitors who want to see these fossils and rocks (leaving them in place, of course!) have a particularly good opportunity to see the cliff face and historic Indian Ladder site on the Indian Ladder Trail, which goes below the cliff face. (The “Indian Ladder” name comes from the colonial era of New York. In the early 1700s, a foot trail from Albany to points west crossed the cliff, and a tree was cut down and propped against it, with the branches cut near their bases to serve as rungs.) Along this trail, visitors can see and touch the same rocks that were known as “the key to the geology of North America”.

NPS photo.

Administered by the National Park Service, the National Natural Landmark Program recognizes and supports the voluntary conservation of exemplary biological and geological sites that illustrate the nation’s natural heritage, including those that contain significant paleontological resources. National natural landmarks are designated by the Secretary of the Interior and are owned by a variety of public and private stewards. To date, significant paleontological resources have contributed, in whole or in part, to the designation of 58 National Natural Landmark sites across the country, and paleontological resources are known at many others as well. These landmarks represent the range of geologic history from very early marine life 510 million years ago to more recent (40,000 years ago) fossil mammals.

Photo courtesy of John Boyd Thacher State Park.

References

-

Venti, N. L, C. Ver Straeten, S. C. Osgood, and A. L. DiTroia. 2021. Evaluation of John Boyd Thacher State Park, Albany County, New York, for its merits in meeting national significance criteria as a National Natural Landmark. Massachusetts Geological Survey, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts. Contract report for the National Park Service. 144 pages.

Related Links

Last updated: September 27, 2024