Part of a series of articles titled On Their Shoulders: The Radical Stories of Women's Fight for the Vote.

Article

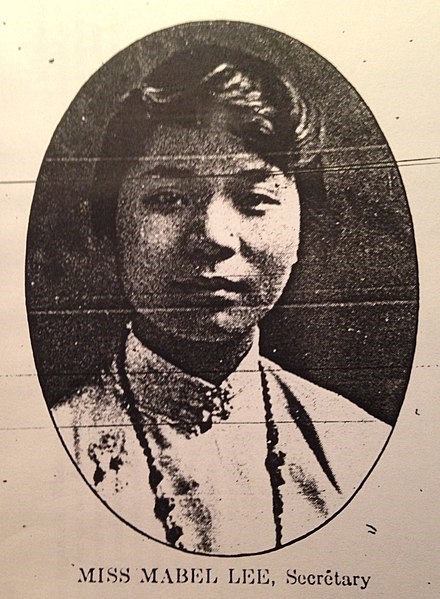

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee: How Chinese-American Women Helped Shape the Suffrage Movement

By Cathleen D. Cahill

In 1912, suffrage leaders in New York invited sixteen-year-old Mabel to ride in the honor guard that would lead their massive suffrage parade up Fifth Avenue. In order to understand why they asked and why Mabel agreed, we have to enlarge the scope of our vision and realize that conversations about women's rights and suffrage were happening all over the world. Suffragists in the United States were part of these transnational discussions.

Mabel Lee was one of the very few Chinese women who lived in the United States in the early twentieth century. This was because Congress had passed harsh laws aimed at keeping Chinese immigrants out of the United States. In the mid-nineteenth century, men from China came to work in the mines and to build the railroads. White Americans held many negative stereotypes about the "Oriental" Chinese fueled by the prevalent bias of the period, assuming the Chinese had inherently “passive” or “servile” natures that made them unable to participate in democratic governments. Immigration laws codified these racist ideas about who could be an American citizen. Specifically, Congress passed two laws to exclude Chinese people from entering the United States. The first law, the Page Act of 1875, was aimed at Chinese women, though it used the language of excluding prostitutes (most Americans believed any Chinese woman who was immigrating was coming to the United States for the purpose of serving as a prostitute). The second law, the 1882 Exclusion Act, dramatically shrunk the number of Chinese immigrants (men and women) admitted into the United States and denied that they could become naturalized citizens. This made the Chinese the only people in the world who were ineligible to become US citizens. This law was renewed every ten years and extended to other Asian countries in 1924. As a result, most of the Chinese people in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century were men, and the vast majority lived on the West Coast or in Hawaii Territory.

Mabel Lee immigrated to the United States from Canton (now Guangzhou), China, around 1900 when she was roughly five-years-old. Her family lived in New York City, where her father served as the Baptist minister of the Morningside Mission in Chinatown. Her parents, Lee Towe and Lee Lai Beck (their names were spelled the Chinese way with surnames first) were able to immigrate under one of the very few exceptions to the Exclusion Act, because they were teachers working for the Baptist Church. As a teacher in China, Mabel's mother was aware of the conversations feminists in that country were having about women's rights. Both she and Mabel's father raised their only child as a modern woman. For example, they chose not to bind Mabel's feet (though Lai Beck's mother had bound hers) and encouraged her education. Her father taught her Chinese classics, but they also sent her to public school in New York. She was the only Chinese student in her graduating class.

White suffrage leaders were also interested in the Chinese Revolution. News spread that the Chinese government had enfranchised women (it was actually more complicated; each province was initially free to determine their own rules on the issue). White suffragists were "glad, but irritated, too," [1] that women in China had won the vote before them. They also wanted to hear more. They turned to local Chinese communities to teach them. Leading Chinese women from cities like Portland, Oregon, Cincinnati, Ohio, Boston, Massachusetts, and New York City, were invited to speak at white suffrage meetings in the spring of 1912. Eager for an audience, Chinese women seized the opportunity to share the news of women's contributions to the founding of their new nation. They told of the women's brigade that fought side-by-side with men in the revolution and celebrated the enfranchisement of Chinese women. At the same time, they appealed to the white women in the audience to help address the needs of Chinese communities in the United States, especially the demeaning immigration laws that they faced.

When she spoke to these famous suffrage leaders, Mabel Lee was only sixteen-years-old and still a high school student, but she had recently been accepted to Barnard College. She reminded her audience that Chinese women in the United States suffered under the burden of not only sexism, but also racial prejudice. She especially urged more equitable educational opportunities for Chinese girls and boys in New York City, as did Grace Typond. Their colleague from Chinatown, Pearl Mark Loo (Mai Zhouyi), called for US citizenship for Chinese women, likely regaling the audience with her own harrowing tale. Before coming to the United States, she had lived in Canton (Guangzhou) and worked as a teacher. She had been involved in the woman's movement there and had edited the Lingnan Women’s Journal. Despite her advanced education, she had been detained by theImmigration and Naturalization Service in San Francisco for months. She, too, believed education was the key to both women’s rights and the strength of a nation, be it China or the United States.

Mabel Lee impressed suffrage leaders so much that they asked her to help lead the parade they were planning later that spring. She agreed. Newspapers across the nation reported on her participation and printed her picture, suggesting great interest from the American audience. Nor was she the only Chinese suffragist in the parade. Her mother and the other women from Chinatown also participated in another section. They proudly carried the striped flag of their new nation as well as a sign stating "Light from China." Though Americans widely believed their cultural values were superior and needed to be shared with China, this slogan reversed that idea. Chinese suffragists hoped their participation would refute racist stereotypes and help change US policies towards Chinese immigrants.

White suffragists also emphasized the reversal of roles. Anna Howard Shaw, the president of NAWSA, marched directly in front of the Chinatown contingent. She carried a banner that read: “NAWSA Catching Up with China.” This slogan was directed primarily at shaming American men into supporting women’s suffrage. Although Americans considered themselves modern and China backwards, the enfranchisement of Chinese women suggested otherwise. Shaw's banner suggested that the US was behind China in this arena. This idea remained one that white suffragists periodically invoked over the next few years.

In one such article, titled "The Meaning of Woman Suffrage," she focused on the importance of women's rights to the new nation. "Are we going to build a solid structure" by including women's rights from the beginning, she asked readers. Not doing so would "leave every other beam loose for later readjustment," as she had learned from her experiences in the American suffrage movement. After all, she concluded, "the feministic movement" was not advocating for "privileges to women," instead it was "the requirement of women to be worthy citizens and contribute their share to the steady progress of our country."[2]

When New York state enfranchised women in 1917, Mabel Lee, still not a US citizen, was unable to vote. However, she vowed to become a feminist "pioneer" by entering a Ph.D. program in Columbia University's Department of Political Science, Science, and Philosophy. She earned her doctoral degree in Economics from Columbia in 1921, the first Chinese woman in the United States to do so. Although Chinese suffragists hoped that their actions would help to change US immigration policy, they were disappointed. In fact, in 1924 Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act that further restricted Chinese immigration and expanded those restrictions to all the countries of Asia. Some American-born Chinese women were able to exercise the right to vote (especially in California), but their numbers were small and remained so until immigration policy changes after World War II, when China fought as an ally with the United States.

After earning her degree, Mabel Lee found that there were few opportunities for highly educated Chinese women in the United States. Many of her peers -- both US and Chinese-born -- moved back to China, where they had more options in the new republic. Indeed, she was offered a teaching position at a Chinese university, but ultimately chose to remain in the United States. When her father died, she took over the administration of his mission, which later became the First Chinese Baptist Church in New York. Mabel Lee continued to work with the Chinatown community in that position until her own death in 1965. Members of her church and community fondly remember her and recently dedicated the local post office to her. But for the most part, the role of Chinese suffragists in the United States were overlooked for the majority of the past century. Centennial celebrations are bringing more and more stories like Mabel Lee's to light. To be sure, the numbers of Chinese and Chinese-American suffragists in the United States were small, but they played a visible and important role in the suffrage struggle. They advocated for a movement that fought for equality of sex and race; they taught white suffrage leaders about the global scope of the fight for women's rights; and they advocated for women's rights in the new Chinese Republic.

Author Biography

Cathleen D. Cahill is an associate professor of history at Penn State University. She is a social historian who explores the everyday experiences of ordinary people, primarily women. She focuses on women's working and political lives, asking how identities such as race, nationality, class, and age have shaped them. She is also interested in the connections generated by women's movements for work, play, and politics, and how mapping those movements reveal women in surprising and unexpected places. Her first book, Federal Fathers and Mothers: A Social History of the United States Indian Service, 1869–1932 (University of North Carolina Press, 2011), won the Labriola Center American Indian National Book Award and was a finalist for the David J. Weber and Bill Clements Book Prize. Her most recent book, Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement (University of North Carolina Press, Fall 2020) follows the lead of feminist scholars of color calling for alternative "genealogies of feminism." It is a collective biography of six suffragists -- Yankton Dakota Sioux author and activist Gertrude Bonnin (Zitkala-Ša); Wisconsin Oneida writer Laura Cornelius Kellogg; Turtle Mountain Chippewa and French lawyer Marie Bottineau Baldwin; African-American poet and clubwoman Carrie Williams Clifford; Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, the first Chinese woman in the United States to earn her PhD ; and New Mexican Hispana politician and writer Nina Otero Warren -- both before and after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. She also serves on the advisory committee for the National Votes for Women Trail and is the steering committee chair of the Coalition for Western Women's History.

Footnotes

[1] “Suffragists Feel Like Going to China,” New York Daily Tribune, March 23, 1912.

[2] Mabel Lee. “The Meaning of Woman’s Suffrage.” Chinese Student Monthly (May 12, 1914), 526-31.

Bibliography

DuBois, Ellen Carol. “Woman Suffrage: The View from the Pacific.” Pacific Historical Review 69 no. 4 (November 2000): 539-551.

Edwards, Louise P. Gender, Politics, and Democracy: Women's Suffrage in China. Stanford, California: Stanford UP, 2008.

Cahill, Cathleen D. Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

“Chinese Girl Wants to Vote: Miss Lee Ready to Enter Barnard, to Ride in Suffrage Parade.” New York Tribune. April 13, 1912.

Lee, Mabel. “China’s Submerged Half.” C. 1915. Unpublished Speech. Files in First Chinese Baptist Church (“FCBC”).

Lee, Mabel. "The Meaning of Woman’s Suffrage," The Chinese Students' Monthly (May 12, 1914), 526-531.

“Mabel Lee Memorial Post Office Dedication Ceremony.” New York news in USPS News, November 28, 2018, accessed March 30, 2020.

National Park Service. “Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.” U.S. Department of the Interior, March 5, 2020.

Schuessler, Jennifer. “The Complex History of the Women's Suffrage Movement.” The New York Times. August 15, 2019.

“Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote.” The Library of Congress. June 4, 2019.

“Suffragists Feel Like Going to China,” New York Daily Tribune, March 23, 1912.

Tseng, Timothy. “Unbinding Their Souls: Chinese Protestant Women in Twentieth-Century America.” In Women and 20th Century Protestantism, edited by Margaret Lamberts Bendroth and Virginia Lieson Brereton, 136–63. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Wing, D. “The Story of Tien Fu Wu: Rescued Slave, Human Rights Advocate and Translator for Justice.” Flickr, accessed March 30, 2020.

Yung, Judy. UnBound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Yung, Ed. Judy. Unbound Voices: A Documentary History of Chinese Women in San Francisco. University of California Press, 1999.

Cathleen D. Cahill is an associate professor of history at Penn State University. She is a social historian who explores the everyday experiences of ordinary people, primarily women. She focuses on women's working and political lives, asking how identities such as race, nationality, class, and age have shaped them. She is also interested in the connections generated by women's movements for work, play, and politics, and how mapping those movements reveal women in surprising and unexpected places. Her first book, Federal Fathers and Mothers: A Social History of the United States Indian Service, 1869–1932 (University of North Carolina Press, 2011), won the Labriola Center American Indian National Book Award and was a finalist for the David J. Weber and Bill Clements Book Prize. Her most recent book, Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement (University of North Carolina Press, Fall 2020) follows the lead of feminist scholars of color calling for alternative "genealogies of feminism." It is a collective biography of six suffragists -- Yankton Dakota Sioux author and activist Gertrude Bonnin (Zitkala-Ša); Wisconsin Oneida writer Laura Cornelius Kellogg; Turtle Mountain Chippewa and French lawyer Marie Bottineau Baldwin; African-American poet and clubwoman Carrie Williams Clifford; Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, the first Chinese woman in the United States to earn her PhD ; and New Mexican Hispana politician and writer Nina Otero Warren -- both before and after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. She also serves on the advisory committee for the National Votes for Women Trail and is the steering committee chair of the Coalition for Western Women's History.

Footnotes

[1] “Suffragists Feel Like Going to China,” New York Daily Tribune, March 23, 1912.

[2] Mabel Lee. “The Meaning of Woman’s Suffrage.” Chinese Student Monthly (May 12, 1914), 526-31.

Bibliography

DuBois, Ellen Carol. “Woman Suffrage: The View from the Pacific.” Pacific Historical Review 69 no. 4 (November 2000): 539-551.

Edwards, Louise P. Gender, Politics, and Democracy: Women's Suffrage in China. Stanford, California: Stanford UP, 2008.

Cahill, Cathleen D. Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

“Chinese Girl Wants to Vote: Miss Lee Ready to Enter Barnard, to Ride in Suffrage Parade.” New York Tribune. April 13, 1912.

Lee, Mabel. “China’s Submerged Half.” C. 1915. Unpublished Speech. Files in First Chinese Baptist Church (“FCBC”).

Lee, Mabel. "The Meaning of Woman’s Suffrage," The Chinese Students' Monthly (May 12, 1914), 526-531.

“Mabel Lee Memorial Post Office Dedication Ceremony.” New York news in USPS News, November 28, 2018, accessed March 30, 2020.

National Park Service. “Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.” U.S. Department of the Interior, March 5, 2020.

Schuessler, Jennifer. “The Complex History of the Women's Suffrage Movement.” The New York Times. August 15, 2019.

“Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote.” The Library of Congress. June 4, 2019.

“Suffragists Feel Like Going to China,” New York Daily Tribune, March 23, 1912.

Tseng, Timothy. “Unbinding Their Souls: Chinese Protestant Women in Twentieth-Century America.” In Women and 20th Century Protestantism, edited by Margaret Lamberts Bendroth and Virginia Lieson Brereton, 136–63. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Wing, D. “The Story of Tien Fu Wu: Rescued Slave, Human Rights Advocate and Translator for Justice.” Flickr, accessed March 30, 2020.

Yung, Judy. UnBound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Yung, Ed. Judy. Unbound Voices: A Documentary History of Chinese Women in San Francisco. University of California Press, 1999.

Tags

- belmont-paul women's equality national monument

- women's rights national historical park

- women's history

- political history

- suffrage

- 19th amendment

- civil rights

- asian american history

- chinese american history

- chinese history

- education history

- international relations

- immigration and migration

- religious history

- new york

Last updated: December 14, 2020