Last updated: December 9, 2024

Article

In Their Own Words

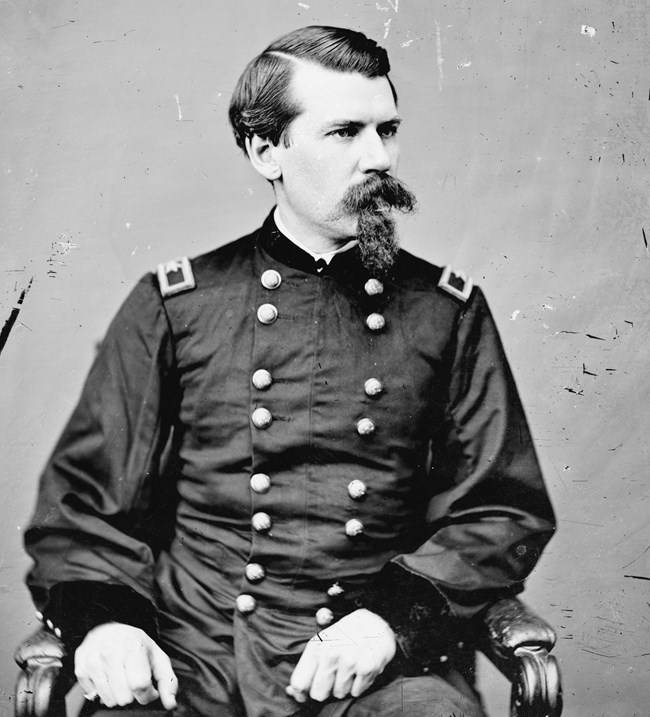

Library of Congress

Horace Porter

Lieutenant Horace Porter served as chief of ordnance for the United States forces on Tybee Island. He oversaw the movement of guns, supplies, and ordnance for the batteries bombarding Fort Pulaski. On April 11, 1862, he wrote:"My dear Father,

Pulaski is ours, Sumter is avenged! We commenced upon it with thirty four guns yesterday morning at 8 ¼ O’clock. By direction of the General, I pointed and armed fired the first gun with my own hands. This was the signal for all our guns to open. Then our battery got peppered from the fort shots flew around our heads as thick as flies on a hot day. Yesterday three of our guns did not work well and night closed without much encouragement. I worked all night in putting these guns in order and in the morning they worked beautifully. At ten minutes past two this afternoon the white flag appeared! You can imagine the scene among our troops. Gen. Benham took my hand in both his and thanked me for my services.

We lost one killed. One was slightly wounded. The Rebels lost one killed and had two wounded. We took 350 prisoners. I will give you more particulars soon. I have scarcely closed my eyes for thirty six hours.

Your Affe. Son

H.P.

Give my love to all at home."

Library of Congress

Nellie Kinzie Gordon

Although she was originally from Chicago, Savannah socialite Nellie Kinzie Gordon was a fervent supporter of the Confederacy in the early war years. This was largely to dispel suspicions held by many of her neighbors. As the war went on, Gordon became increasingly disillusioned.

On May 4, 1862, Gordon wrote in her diary, just returned from a trip to Virginia:

"To think of my not having written a line in here since I arrived. So many important events having taken place, too!

First of all the fall of Pulaski, a disgraceful surrender! Why didn’t the garrison destroy all their powder & then when the enemy had shelled them until they were tired and attempted to breach the fort fought with cold steel! Phaw! It’s disgusting!...Am going away somewhere—I fear this will be a long, long War…"

NPS

Lemuel Wilson Landershine

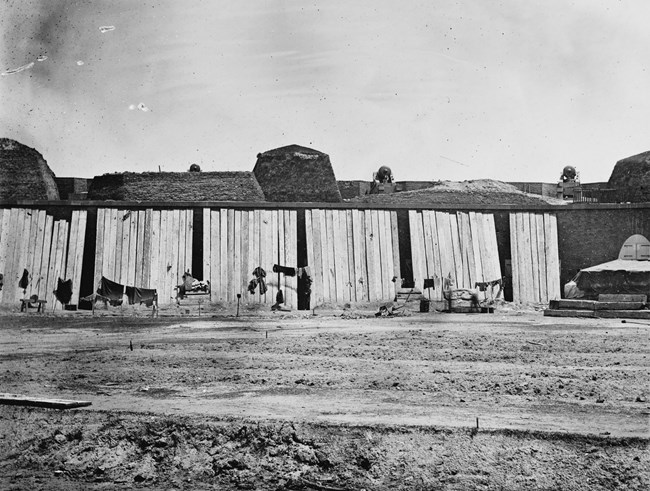

Lemuel Wilson Landershine was a part of the Confederate garrison at Fort Pulaski and recorded his time in a diary. This excerpt reads from his entries during the bombardment.

"... although the heavy shot from the Battery at Kings would come whistling round the old fort the boys would return them shot for shot. Whenever the boys on the ramparts would see a good shot made by anyone from the fort you could hear them give cheer after cheer. Whenever the boys would cheer anyone near the Colonel could see his face brighten with pleasure…

The Battery at Kings Landing composed of rifled guns was the only one that was doing us any damage…. The Balls and shells from these guns were the only ones that the boys on the ramparts paid any attention to…By afternoon the port holes of the casemates in the South face of the fort had been greatly enlarged by the enemy and their shots and shells were corning into the casemates… I then took a walk round the fort and was astonished at what damage had been done… After going the rounds of the fort I came to the conclusion that we would be obliged to give the fort up.

11th.

...Things went on as yesterday the enemy were now gradually enlarging the breech made and had commenced another in the adjoining casemate…The shots of the enemy were now passing clear through the fort and striking the walls of the north magazine…when about 2 1/2 p.m. I seen Col Olmstead and Capt. Sims go pass with a rammer and sheet, we all knew that it was over with us and we would have to give up. Soon the word was passed that the "White Flag" was up. The firing now ceased on both sides. I went outside the fort and it was a perfect wreck on the south face of the fort..."

Library of Congress

Susie King Taylor

Susie King Taylor was enslaved for the first fourteen years of her life. When Fort Pulaski fell, she and countless other enslaved people seized the opportunity and ran to Union lines where they found freedom. Taylor went on to serve as a nurse and laundress for the 33rd United States Colored Troops and recorded her experiences of that time, as well as of April 10-11, 1862, in her memoirs.

"About this time I had been reading so much about the 'Yankees.' I was very anxious to see them…I wanted to see these wonderful 'Yankees' so much, as I heard my parents say the Yankee was going to set all the slaves free. Oh, how those people prayed for freedom…

On April 1, 1862, about the time the Union soldiers were firing on Fort Pulaski, I was sent out into the country to my mother. I remember what a roar and din the guns made. They jarred the earth for miles. The fort was at last taken by them. Two days after the taking of Fort Pulaski, my uncle took his family of seven and myself to St. Catherine Island. We landed under the protection of the Union fleet, and remained there two weeks, when about thirty of us were taken aboard the gunboat P--, to be transferred to St. Simon's Island; and at last, to my unbounded joy, I saw the 'Yankee.'"

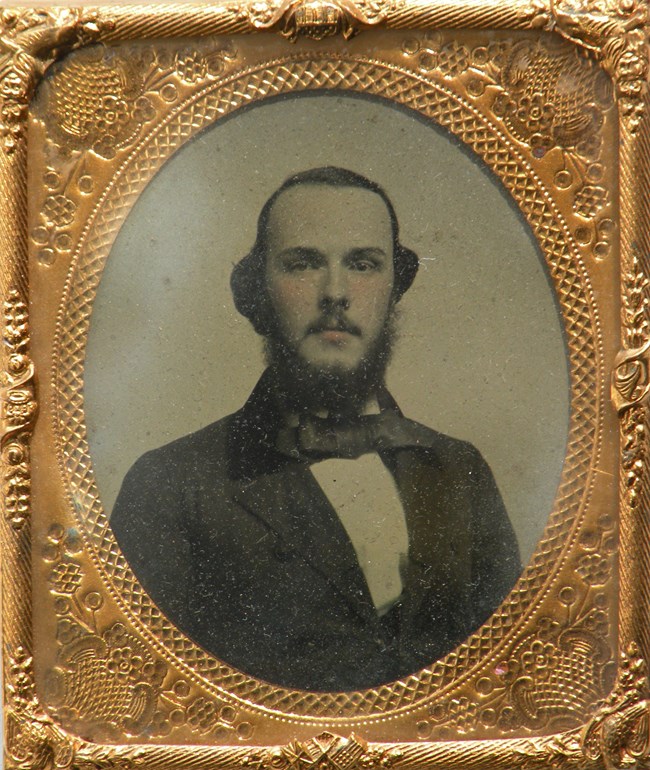

NPS

Charles Hart Olmstead

Charles Hart Olmstead was born in Savannah and attended the Georgia Military Institute. In 1861, he was given command of the Confederate garrison inside Fort Pulaski. On April 11, 1862, he wrote to his wife:

"My dear wife,

I address you under circumstances of the most painful nature. Fort Pulaski has fallen and the whole garrison are prisoners.

…It soon became evident to my mind that if the enemy continued to fire as they had begun the walls must yield. Shot after shot hit immediately about our embrasures…

Officers and men behaved most gallantly, everyone was cool and collected...The men when ordered on the parapet, went immediately with the most cheerful alacrity, though the missiles of death were flying about at the most fearful rate. Thirteen- inch mortar shells, Columbiad shells, Parrott shells, rifle shots were shrieking through the air in every direction, while the ear was deafened by the tremendous explosions that followed each other without cessation...

On taking a survey of the Fort after the firing had ceased, my worst fears were confirmed, the Angle immediately opposed to the fire of the enemy was terribly shattered and I was convinced that another day would breach it entirely.

…I found that the breach in our wall had become so alarmingly large that shots from the batteries of the enemy were passing clear through and striking directly on the brickwork of the magazine. It was simply a question of a few hours as to whether we should yield or be blown into perdition by our own powder…

I gave the necessary orders for a Surrender. Oh, my dear wife, how can I describe to you the bitterness of that moment. It seemed as if my heart would break. I cannot write now all the details of our surrender, it pains me too much to think of them now..."

National Archives

James Wilson

James Wilson served as a topographical engineer for the U.S. forces stationed on Tybee Island. Prior to the bombardment, he delivered the Union army's demand of surrender to the Confederate garrison inside Fort Pulaski. On April 30, 1862, he wrote fellow Union general James McPherson:

"My dear McPherson

…Your letter of the 8th ult, found us engaged in the very heavy work of preparing for the reduction of Pulaski, it was tedious very laborious and above all experimental. Gen’l Gillmore and the young men had to contend with the fears, doubts, adverse opinions and remonstrances of old fogies as well as natural obstacles of no insignificant character…In face of all this Gillmore hung out, carried out his plans and attacked the fort, with what success you know.

At the distance of 1700 yards, in about 17 hours firing two breaches entirely practicable were effected and two others opened. In two days more we would have battered down the entire face exposed to our direct fire...The whole affair is replete with instinctive results. The most important of which, I consider to be that the ordinary thickness of brick escarpments is not sufficient to resist breaching operations at anything less than 2500 yards with a judiciously selected batteries of heavy rifles and 10 in guns I have no hesitation in saying that a breach can be effected at this distance quite as easily as at 300 yards with the old fashioned arm. Notwithstanding all this, so far as concerns the danger of siege operations, the old fashioned works will answer admirably the primary purpose of delaying the enemy. Pulaski has kept us out of Savannah for four months, and we are not there yet and probably will not be soon..."

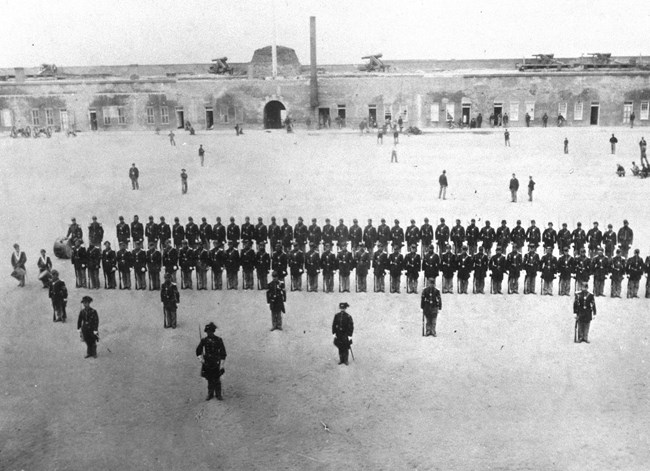

NPS

William B. Howard

Corporal William B. Howard served in Company F of the 48th New York Infantry, who witnessed the bombardment from nearby Daufuskie Island. Howard kept a diary during his time in the 48th, which spanned from his enlistment in September 1861 to just prior his wounding at the failed Union assault on Fort Wagner in July 1863.

"April 10th 1862

Bombardment of Fort Pulaski. Commenced at 8 O Clock precisely…Soon as I got relieved went up to the Genl’s quarters as fast as possible and secured a fire view, and while sitting there the long roll beat to quarters, ran back to secure my arms & ammunition and fell in line. After the regiment was formed, we stacked arms and was dismissed with permission to watch the bombardment…the whole shore of Tybee had opened upon the Fort. Firing continued all day and night – without any pausing whatever.

April 11th 1862

No cessation of firing this morning. Fire is more rapid than yesterday. At long intervals the Fort replies but they appear to be giving in. 2 and 30 P.M…the rebel flag came down the Fort has surrenderd. The bombardment lasted 36 hours.

April 12th 1862

This morning the Stars & stripes are waving from the ramparts of Pulaski. The fleet runs up the river to the Fort.

April 13th 1862

Col. Perry and Dr. Mulford goes to the Fort various rumors circulating in Camp that we are to garrison the Fort. A great deal of grumbling at the receipt of this news."