Last updated: April 29, 2023

Article

Groundwater Monitoring

NPS / Stacy Manson

Water in the Desert

Water is one of the scarcest resources in Joshua Tree National Park (JTNP), shaping the Mojave and Colorado desert ecosystems within the park. Life-giving water becomes available to plants and wildlife in a variety of ways. It falls as rain (2 to 7 inches a year), then flows through ephemeral creeks and washes.

Water also bubbles from the ground as natural springs in canyon oases where geologic faults let groundwater reach the surface. Before the park was established, ranchers and miners intercepted rainwater in washes and stored it in small reservoirs that became resources for wildlife. Today, most water for human use in the park comes from wells that tap aquifers deep beneath the earth’s surface.

Why Monitor Water?

Climate change is affecting the availability of water in the park. From 1895 to 2016, as the average temperature increased by 3°F (2°C), annual precipitation dropped by 39 percent. In a recent study of 45 historic desert springs within park boundaries, 39 had surface water in 2006 but only 12 had water in 2016—and as of 2023, only two perennially flowing springs remain in the park, at Smithwater Canyon and Fortynine Palms Oasis.

Population growth outside park boundaries is also a factor in groundwater availability. For example, groundwater withdrawals by the Twentynine Palms Water District have exceeded recharge rates, contributing to declines in groundwater levels at the park’s Oasis of Mara.

The park’s surface water and groundwater resources have been monitored in various ways over time. For example, the U.S. Geological Survey monitored groundwater levels in 13 park wells from 1958 – 1982. However, a standardized park-wide long-term monitoring program was established only comparatively recently, after water monitoring was identified as a management priority in 2004 by the NPS Mojave Network (MOJN), of which JTNP is a member. In 2006, the MOJN’s Inventory and Monitoring (I&M) Program initiated surveys to inventory springs and identify their management needs in each park.

JTNP’s Underground Water

Since 2007, the park’s drilled well groundwater monitoring program has been measuring the depth of the water table at 24 wells (Table 1), selected for monitoring because they are easy to access, are not in use, and have not been permanently capped. Some of the wells were originally drilled by homesteaders or miners, as drinking water sources or to power miners’ stamp mills; others were drilled by the park for monitoring purposes. Six of the wells were part of the earlier USGS monitoring program. In 2021, a 25th historic well was added (Key Ranch, Well ID 38).

Since 2011, groundwater measurements have been made on a quarterly basis. Park technicians measure the depth from the ground surface to water in the drilled well casing using an electric sounder—essentially a tape measure with an electronic probe on the end. The tape is lowered into the well and when the probe touches water, a circuit closes.

| Well Name | Well ID |

| Cohn Drainage | 241 |

| Cow Camp NPS Test | 282 |

| Cow Camp Sand Point | 280 |

| Desert Queen | 22 |

| Embry | 48 |

| Gold Rose | 67 |

| Howard | 44 |

| Keys Drainage | 240 |

| Mission | 66 |

| NPS Test | 30 |

| Oasis of Mara | (9 wells) |

| Pinto | 82 |

| Sunrise | 65 |

| Test | 29 |

| Wall Street Sand Point | 281 |

| Willets | 19 |

NPS Photo

Program Goals

The JTNP groundwater monitoring program has the following goals:

- Monitor groundwater levels at existing wells in the park.

- Document groundwater trends. Are water levels stable, increasing, or decreasing?

- Analyze groundwater trends as a function of locally monitored precipitation and temperature to understand the impact of climate change on water resources.

- Identify potential management activities that may help protect natural resources that are threatened by dropping groundwater levels (for example, palm tree oases).

- Work with the park’s Interpretation unit to educate visitors on how climate change affects water resources in JTNP.

NPS Graphic

Results

The earlier USGS monitoring effort revealed that, from 1958 to 1975, groundwater levels declined across the park. From 1975 to 1980, a period of increased precipitation, water levels increased.

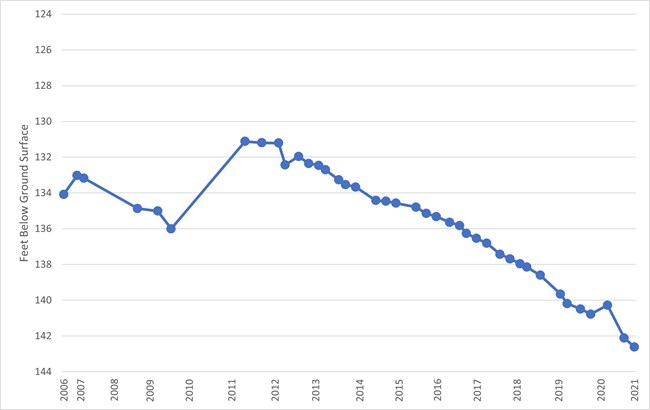

An analysis of data from the 24 wells monitored since 2007 reveals that overall, the water table has dropped in most parts of the park. For example, at Willets Well (northwest of the the Quail Springs picnic area), the water level in the test well casing dropped 11 feet between recent high-water year 2012 and 2021 (Figure 3). At the Embry well, 2/3 of a mile SW of Willets, the water level dropped more than 15 feet during the same period; in 2021, the sounder probe encountered no water even at the very bottom of the 96.53 ft casing.

Pinto Well, in the eastern portion of the park, was the only well to see an increase in water level (+1.27 ft) from 2007-2021. Climate change and the decreased availability of water in the park present real threats to Mojave desert birds, desert tortoises, bighorn sheep, and other iconic park species and communities. Spring and groundwater monitoring will be essential tools for understanding and managing park resources in an uncertain future.

Management Applications

The ultimate goal of water resource management in the park is to support natural, stable populations of plants and wildlife with minimal interventions. Desert bighorn sheep are one species that has been negatively affected as surface water becomes less available in the park; park scientists are evaluating whether or not to support herds in the park with artificial water sources called “guzzlers.” More challenges like this one are likely to arise if groundwater levels in the park continue to decline.