Last updated: August 23, 2024

Article

Grand Junction, CO

US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

Article written by Richie Ann Ashcraft and Malaika Michel-Fuller, Contractors to the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management

The United States was on a mission to develop an atomic bomb more than 80 years ago and they needed uranium—a rare ingredient—to succeed. The Manhattan Engineer District relied heavily on Canada and Africa for raw uranium for the Manhattan Project, which was a secret research and development program that created the first atomic weapons during World War II. The government recognized the risk in getting the uranium from Canada and Africa so needed a domestic uranium source.

Land in Western Colorado and Eastern Utah had the highest known uranium-ore concentrations in the country. The federal government chose Grand Junction, Colorado, the largest town in the area, to become a uranium processing site, making Grand Junction very important to the Manhattan Project.

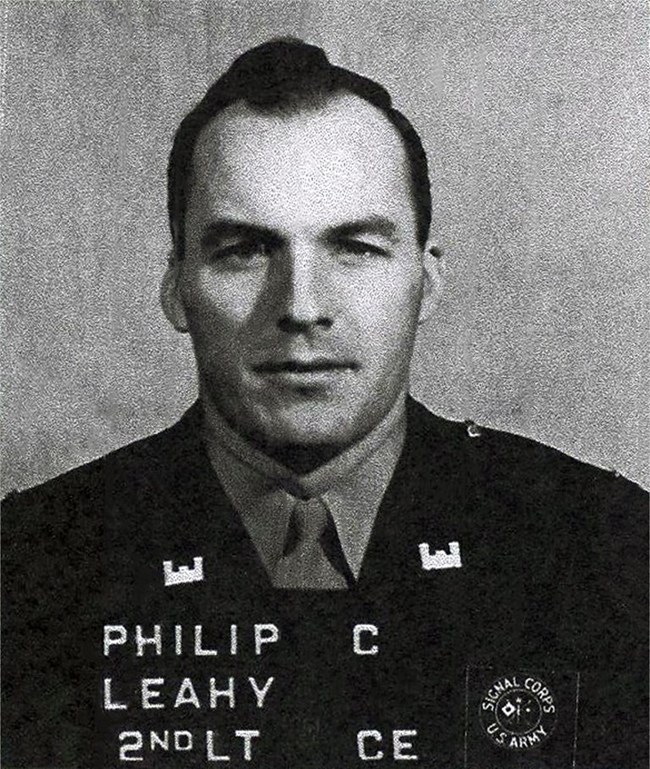

While working at the Manhattan Project’s Metallurgical Laboratory in Illinois in 1943, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Second Lieutenant Philip C. Leahy, a civil engineer by training, met Lieutenant Colonel Thomas T. Crenshaw, who supervised project’s uranium procurement. Crenshaw told Leahy to pack his bags and board a train for a new assignment. It wasn't until Leahy got off the train that he knew where the project was: Grand Junction, Colorado.

As the head of the Manhattan Project’s newly established Colorado Engineer Office, Leahy’s assignment was to procure as much uranium as possible from the Colorado Plateau. He set up his office in downtown Grand Junction.

He also purchased 55 acres (22.25 hectares) of land tucked behind Grand Junction’s municipal cemeteries. Formerly a gravel pit, workers quickly converted the site into a new uranium refinery. A log cabin on the property served as the refinery’s office.

The site was the perfect place for a secret operation. It already had a rail spur where workers could load and ship materials without inviting public scrutiny. Though just outside city limits, there was little drive-by traffic. Also, the Gunnison River surrounded the site on three sides, supplying plenty of water for refinery work and limiting outsider access by land.

By 1946, the Colorado Plateau had produced more than 2.6 million pounds (1179.34 metric tons) of uranium oxide, or “yellowcake,” which was about 14% of the total uranium acquired for the Manhattan Project. At the time, the public knew little about the mill’s activities, and news reports claimed the mill was producing vanadium, an important steel hardening element used in the war effort.

Today, there is no secret about Grand Junction’s involvement in the Manhattan Project. In 2001, the Department of Energy (DOE) transferred ownership of the former refinery site to the Riverview Technology Corporation, known as RTC, a local nonprofit the city of Grand Junction and Mesa County formed to develop the economy and create and keep jobs. After the transfer, RTC began leasing the cabin to DOE. These organizations worked together to create the Atomic Legacy Cabin.

The Atomic Legacy Cabin is a public interpretive center that tells the history of uranium mining and milling on the Colorado Plateau through informational and interactive displays. Along with most of the former refinery site, the Atomic Legacy Cabin is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is used for public programming and science, technology, engineering, and math, or STEM, education.

US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

Chenoweth, William L. 1996. “Raw Materials Activities of the Manhattan Project on the Colorado Plateau.” Nonrenewable Resources 6 (1): 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02816923.

Hadden, Gavin, ed. 1947. “Book VII, Volume 1.” In Manhattan District History. Washington, D.C.: United States Atomic Energy Commission. https://www.osti.gov/includes/opennet/includes/MED_scans/Book%20VII%20-%20%20Volume%201%20-%20Feed%20Materials%20and%20Special%20Procuremen.pdf.

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service. 2016. “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.” National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. June 10, 2016. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail/fb8689b7-b4ef-4bc8-8240-2f662ecaed55.