Last updated: October 7, 2022

Article

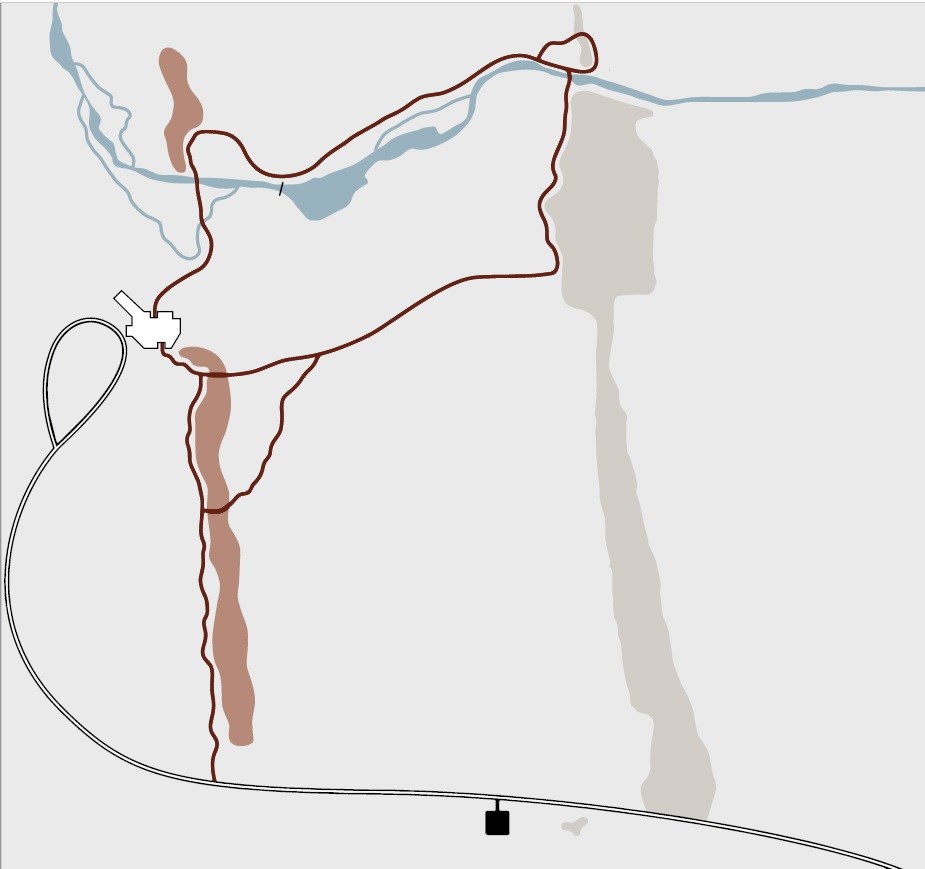

Digital Circle Trail Tour

NPS

Pipestone National Monument exists to protect the rights of all American Indians enrolled in federally recognized tribes to quarry this soft, red stone. This is a sacred site to many people and consists of a tallgrass prairie that supports over 500 plant species and a diverse array of wildlife.

NPS/N.Barber

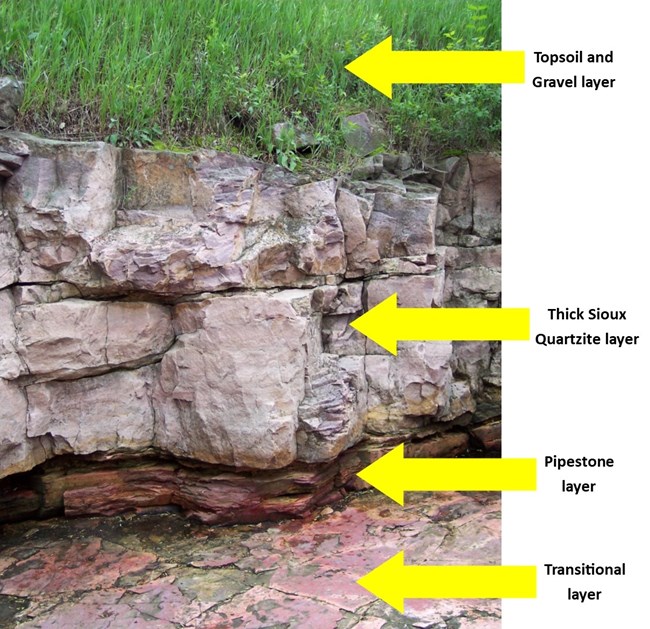

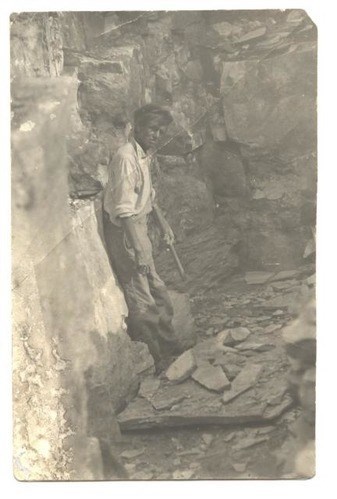

The Exhibit Quarry

After exiting the Visitor Center through the south doors, the first stop is the Exhibit Quarry. In the 1940s, this quarry was renovated by quarriers so you can also physically experience being in a quarry. This quarry represents the historical, cultural, and geological significance of the site. For many American Indians who quarry, the process of quarrying is spiritual.The hard, physical labor involved is a commitment of the spirit that tests all quarriers, creating a sense of connection. The very bottom layer of rock is pipestone, and above is Sioux Quartzite and soil, which must be removed by hand to expose the pipestone.

NPS/Public Domain

The South Quarry Trail

At the first fork in the trail where the path veers to the right is a line of active quarries where American Indians have continuously quarried pipestone for centuries. Many travel great distances, spending a week or more of vacation time from their regular jobs. High humidity, heat, rain, mosquitoes, ticks, thorns, poison ivy, and lack of shade all combine to make quarrying a personal struggle.Using heavy sledgehammers, pry bars, and wedges to break through the hard quartzite and hauling buckets of heavy rubble also make it an exhaustive struggle. Despite all this hardship, the quarrying of pipestone continues today from spring through fall.

American Indian people hold pipestone in great reverence and many oral histories tell of its origin. A belief held by many is that the stone was formed from the flesh and blood of their ancestors.

NPS/C.Goraczkowski

The Inkpaduta Campsite

After the 1857 Spirit Lake Massacre in Iowa, Dakota leader Inkpaduta camped with his band and their captives on this prairie – as did at least one force of pursuing troops. One of the survivors, Abigail Gardner, revisited the site in 1892 and pointed out the location of the campsite, which was on the grassy flat area just south of the trail. She also recalled watching the Dakota band engage in quarrying pipestone while they were there so that they could make pipes.Typically, people did not camp next to the quarries because they considered the site a neutral and sacred space. They generally camped on higher ground and entered the actual quarry area for the purpose of obtaining pipestone.

NPS

Tallgrass Prairie

The landscape surrounding the Circle Trail is covered in Tallgrass Prairie. This was once the largest contiguous ecosystem in North America, extending from Canada to Texas, and from Indiana to Kansas. Due to rural and urban development, approximately 2% remains today.Euro-American settlement and the introduction of non-native plant species has dramatically changed the tallgrass prairie plant composition. The Monument has conducted annual prescribed fires since 1971 to restore native plants.

NPS

Nature's Forces

As the trail turns along Sioux Quartzite outcroppings nearly 20 feet high, visitors also see grass and shrubs able to grow through expanding cracks in the rocks. Nature’s forces take their time and move slowly. Lichens may spread over the entire surface at a rate of an inch or less per century and live for thousands of years. They currently cover approximately 8% of the Earth’s surface.

NPS

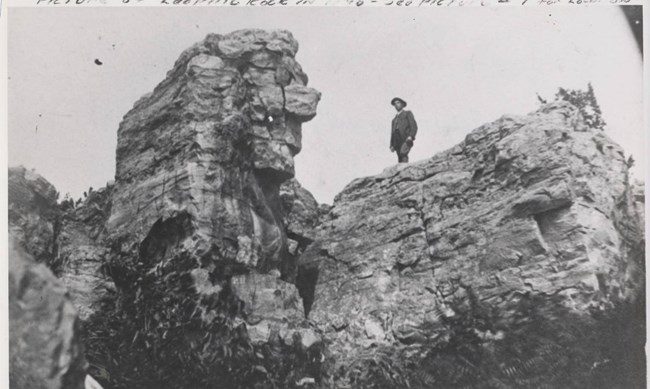

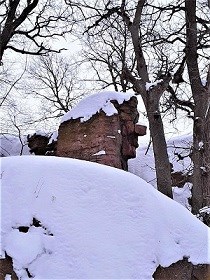

The Oracle

Climbing steps to an overlook provides a good vantage point for viewing The Oracle – the profile of a face that can be seen in the rocks. A story has been told that quarriers left offerings for The Oracle in exchange for wisdom.Some Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate tribal members interviewed in the 1990s stated a belief that Lyle Linch, an early park superintendent, invented the idea of The Oracle for tourists in the 1940s. However, some tribal members also stated that the feature was - and still is - traditionally important to them.

Just like any feature in a sacred space, its impact is personal to the one having that experience. Offerings are left near The Oracle today.

NPS/N.Barber

Sioux Quartzite Outcroppings

The rock wall along the trail is Sioux Quartzite, which overlies the pipestone. Since the rock layers slope 8° downward from the quarries near the Visitor Center to the cliffs where you’re standing, the pipestone layer would be roughly 100 feet underground at this point.Sioux Quartzite is one of the world’s oldest rocks (over 1.6 billion years old) and is found throughout southwest Minnesota and southeast South Dakota. Early settlers used it as building material, and parts of the Visitor Center are made with Sioux Quartzite. Pipestone is not used for buildings because of its softness (which is similar to soapstone).

Winnewissa Falls

Left image

Old photo of Winnewissa Falls

Credit: NPS

Right image

Winnewissa Falls in 2019

Credit: NPS/N.Barber

NPS

Leaping Rock

Following the steps up the side of Winnewissa Falls, the path brings visitors to Leaping Rock. Early explorers noted arrows stuck in the cracks on top of Leaping Rock. They learned from various tribes that warriors, to prove their bravery, jumped from the cliff onto the top of Leaping Rock roughly 12 feet away and jammed an arrow into one of the cracks. It was also said that occasionally, a woman might refuse the attention of a warrior until he had shown his bravery by jumping onto Leaping Rock.One Mandan warrior told Catlin, “I am a young man, but my heart is strong. I have jumped on the medicine-rock - I have placed my arrow on it and no Mandan can take it away. The red stone is slippery, but my foot was true - it did not slip.”

It was a dangerous ritual. Catlin wrote about seeing a Dakota father mourn the death of his son, who had slipped while making the attempt.

During Joseph Nicollet’s famous 1838 expedition, 25-year-old John C. Fremont (who later became a famous explorer and Civil War general) jumped onto Leaping Rock and placed an American flag on it.

NPS/N.Barber

Nicollet Marker

Just past Leaping Rock is the Nicollet Marker. The initials on this rock were carved by the French scientist Joseph Nicollet and members of his 1838 expedition. This was the first US government-sponsored expedition to the quarries, resulting in the first accurate map of the upper Mississippi and Missouri river basin (which includes Minnesota). When the quarries were turned into a 1-square-mile reservation in 1858, this marker was used as the center point.

NPS

Ripple Marks

As visitors walk down the stone stairway, they often see that some of the quartzite steps have a rippled surface. These ripple marks were formed when the quartzite was still loose sand in shallow water. Ripple marks like this are found on shores of modern lakes, oceans, rivers, and streams.

NPS

Old Stone Face

As the steps lead back to the main trail, visitors can turn back and see Leaping Rock from below in profile. From this view, it is often referred to as 'Old Stone Face.' Like The Oracle, there is no historical evidence that American Indians have ever called this feature anything but Leaping Rock or Medicine Rock.

NPS/N.Barber

Smooth Sumac

The Circle Trail leads visitors by a large patch of smooth sumac. Although green in the summer, the leaves turn a brilliant red in the fall. This native species can tend to crowd out other plants, so it is cut back every year. Park staff also conduct controlled burns annually in alternating sections of the site to encourage native plant diversity and prairie health.

NPS

Lake Hiawatha

Visitors are often just as suprised to see a lake in the prairie as they are a waterfall. This lake was originally a swampy area, but the CCC-ID (Civilian Conservation Corps - Indian Division) built a dam in the 1930s to create a swimming hole for children living at the nearby Pipestone Indian Boarding School. The boarding school was one of many that attempted to assimilate Indigenous children by suppressing Native language, religion, and culture.When the children came here to swim, they learned about quarrying and carving from the active quarriers nearby. Today, in addition to quarrying and carving, the Monument is used regularly for many spiritual and cultural traditions in an area not accessible to visitors, such as (Dakota translation included):

- Sun Dance - wiwáŋyaŋg wačhípi [wee-WAH-yaug wa-CHEE-pee]

- Sweat Lodges - Iníkaǧapi [ee-NEE-kah-ghah-pee]

- Vision Quests - Haŋbdéčheyapi [aw-bDAY-chay-yaw-pee]

NPS/N.Barber

The Spotted Quarry

The Spotted Quarry, visible from the trail, gets its name from the appearance of the pipestone that comes out of it. The dark red stone is speckled with small, white spots which may be from bacteria dying off and causing reduction in the iron-oxide (hematite) when the stone was still sand.Historically, American Indians quarried in the late summer and early fall since they had to wait for flooding in the quarries to recede after snowmelts and heavy rains earlier in the year. Today, the park uses water pumps so that quarriers can begin working earlier if they choose.

NPS

Plant Diversity

American Indians use many of the plants you see in the prairie for food, medicine, and ceremonies. If you know what you’re looking for – and the correct ways to prepare it – the tallgrass prairie can provide an abundance.The Monument contains over 500 species of plants, including one federally threatened species (the Western prairie-fringed orchid) and nearly a dozen state-listed rare species. By leaving what you find here and not picking plants or flowers along the way, you’re helping protect this vanishing ecosystem.

The Three Maidens

Left image

1892 photo of the Three Maidens

Credit: W.H. Holmes, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, photograph 72-3236

Right image

The Three Maidens in 2019

Credit: NPS