Last updated: May 21, 2021

Article

Civil War Connections at Hot Springs National Park

Hot Springs and the War: An Introduction

Congress and President Jackson created Hot Springs Reservation, the precursor to Hot Springs National Park, in 1832. Four square miles in size, it encompassed much of the present-day city of Hot Springs, a thoroughly southern town at that juncture. The 1850 census recorded a total of 361 slaves in Hot Spring County, and the 1860 census recorded 616. By the 1860s, established roads allowed troops of both sides to travel through, sometimes encamping here. Many Hot Springs men of military age signed up with the Confederate Army at the war’s outset. Hiram Whittington, for whom a section of the park is named, was a native of Massachusetts but volunteered to put up money for one Confederate regiment. Skirmishes are recorded as having taken place in the vicinity of Hot Springs, including one with fatalities east of Cedar Glades in 1863. No evidence of such fighting has been found in the park, despite archeological surveys performed at conjectured battle sites. In 1864 federal troops arrested numerous Hot Springs residents who refused to take the loyalty oath.

Hardship

The realities of war made life miserable for civilians. Food, clothing, and shelter became scarce. Independent militiamen of the two sides, called bushwhackers and jayhawkers, burned structures and took potshots at uniformed soldiers. They also murdered and committed mayhem on civilians who harbored the “wrong” sympathies. Many locals fled to Texas, Louisiana, or “the Rock” (Little Rock). As for regular troops, Lieutenant Colonel Henry C. Caldwell, Third Iowa Cavalry (USA), wrote of traveling through this area in 1863: “I subsisted my men, as far as practicable, on the country, and supplied myself liberally with forage, horses, and mules whenever wanted, but I was always careful to see that secessionists supplied me with these wants, and that they were taken in an

orderly manner.” Understandably, civilians trying to survive during lean times resented this. On the other hand, a letter from Major General Frederick Steele (USA) to Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke (CSA) reads in part: “General, permit me to call your attention to a report that has been made to me by a man who is said to be reliable. It is to the effect that a party of soldiers belonging to your division have been hanging citizens in the vicinity of Hot Springs, and elsewhere, on account of their supposed sentiments toward the Government of the United States. I do not believe all the stories that are told me but as this bears the air of probability, I inform you of it under the conviction that you would regard an outrage on the part of troops in the same light that I do myself.”

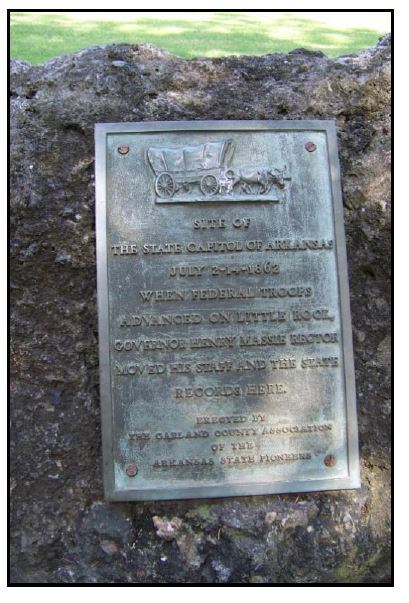

A Capital on Bathhouse Row

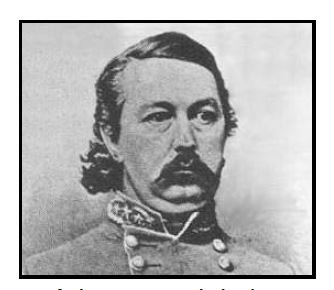

The hot springs had been set aside for federal property, but oversight was non-existent until the 1870s. In fact a Confederate capital briefly occupied Bathhouse Row under then-governor, and staunch Confederate, Henry M. Rector. When Little Rock seemed in danger of falling to the Union, in mid-1862, he came home to the bathhouse and “kitchen” he owned here. By wagon train from Dardanelle, he brought 7 to 9 tons of state archives, funds, and other supplies out of Little Rock. His sudden departure caught the Capital City off-guard, although his popularity had waned for other reasons since his election in 1860. Soon after returning to Little Rock, Rector was voted out of office.

Those Who Came Afterward

Veterans of both sides flocked to Hot Springs after the war, some to bathe their war wounds. Many bathed in the pay bathhouses and others, without money, bathed on the hillside above, in the “dugout pools” of hot water. This led to the first Free Bathhouse for the indigent. Other veterans came to settle; some were returnees who, while assigned to the area during the war, had thought it a beautiful place. Still other veterans arrived to build and operate the bathhouses—Samuel Fordyce (USA), George Latta (CSA), Dr. Algernon Garnett (who had served aboard the ironclad C.S.S. Virginia), and others joined former Governor Rector on Bathhouse Row. Physicians, like Prosper Ellsworth (USA), George Lawrence (CSA), James Keller (CSA, and uncle of Helen Keller), and Evander Ellis (CSA) moved here to practice. Ellsworth and Lawrence had an office together on the Row prior to 1878. Other veterans, L.Q.C. Lamar (CSA) and John W. Noble (USA), have their names preserved in architecture on the Row. General P.T. Beauregard (CSA) and free-thought orator Robert Ingersoll (USA) stopped at Hot Springs after the war. The Reservation’s first three superintendents were Civil War veterans. Many less famous veterans visited and settled here, too. Not all was well, of course: there were Jim Crow laws and lynchings (the last in 1922, near the corner of Central and Ouachita streets).

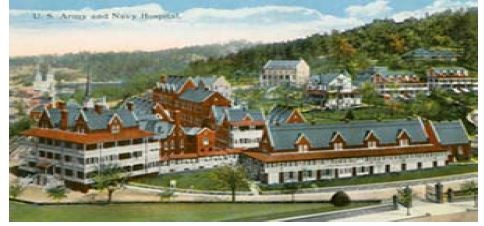

A Giant Emerges

A large hospital resulted from Illinois senator (and former Union general) John A. Logan coming to bathe under the guidance of Dr. Garnett, who told fellow veterans about it. These veterans invited the senator to a special dinner at the Palace Bathhouse, where the Fordyce is today. They made a pitch to Logan to put a federal Army and Navy General Hospital here. The facility opened behind Bathhouse Row in 1887. Its successor became the Hot Springs Rehabilitation Center in 1960—almost one full century after the Civil War began.