Last updated: July 28, 2023

Article

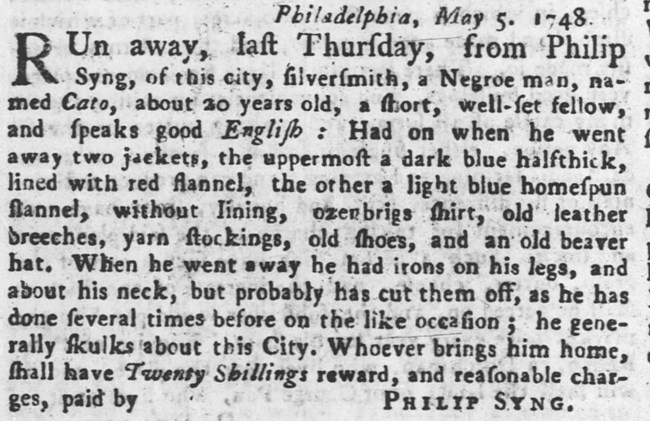

Pennsylvania: Cato, 1748

Silver and Gold: there’s more to the story of the famed “Syng Inkstand.”

All signatories of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States dipped their quill in the same ornate silver inkstand before signing the nation’s founding documents. Such was the stature of Philadelphia silversmith Philip Syng. His elegant gold and silver creations adorned the most prosperous homes of colonial America. Friend to Ben Franklin, founding member of the University of Pennsylvania, who better to provide the vessel from which to declare all men equal in the face of tyranny? Syng first unveiled his signature inkstand in 1752. But did Syng really make the famous piece? A recently unearthed ad, placed by Syng in Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, suggests Syng, at the very least, had help from a young enslaved man named Cato.

In the ad, dated May 5, 1748, Syng offers a twenty-shilling reward for the capture and return of “Cato, about 20 years old, a short, well-set fellow” wearing two jackets, “old shoes” “an old beaver hat,” and “old leather breeches.” That final detail strongly suggests Cato was a craftsman in Syng’s studio. Syng further noted “when (Cato) went away he had irons on his legs, and about his neck, but probably has cut them off, as he has done several times before on like occasion.”

Nothing written about Syng during his lifetime or after mentions that he owned slaves, let alone that he shackled them to ensure they kept smithing his wares. In Syng’s 1748 classified ad, he offered the reward for “whoever brings him home.” Syng blithely suggests Cato’s apprehension should be easy because “he generally skulks about this city.”

Near the time of the ad, estimates suggest there were between 1,000 and 1,500 enslaved people in Philadelphia, then the largest city in the colonies with about 13,000 inhabitants.1 Although Philadelphia was the epicenter of early abolitionist activity, an estimated one in six white households still held at least one Black man or woman in bondage by 1761.2 Many of those enslaved people were tasked with the hands-on work in metallurgy, carpentry, and other workshops in the bustling industrial center. The advantage to shop owners such as Syng: While white apprentices often left to start their own shops upon achieving mastery, enslaved craftsman had no such avenue for advancement.3

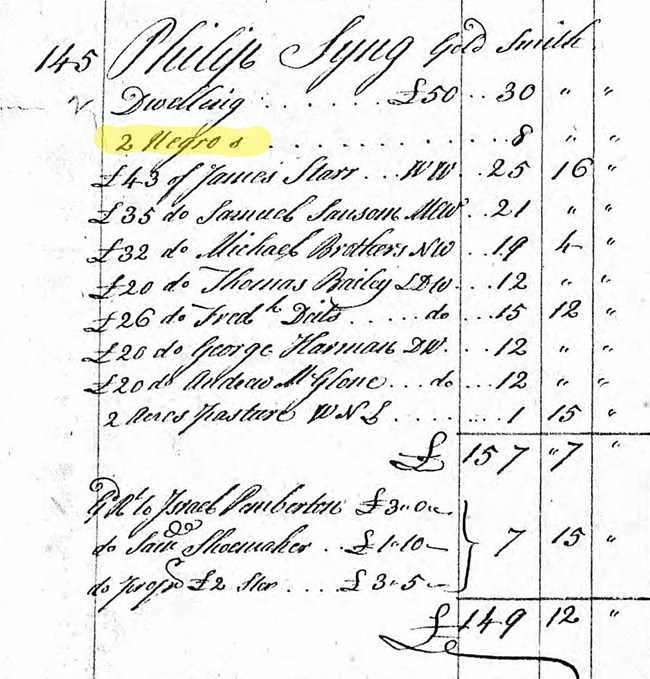

Nothing is known of Cato’s life and career beyond Syng’s one-paragraph appeal for his capture in 1748. It is known, however, that twenty years later, Syng was still paying taxes on “2 Negroes,” according to the city’s 1769 tax records. (Both local censuses and so-called “slave registries” from the region have been lost). Meaning, it also isn’t known if Syng was ever swayed by the growing sentiment centered in Philadelphia that slavery was antithetical to the new nation’s founding documents.

In 1758, the Society of Friends – the Quakers – barred church leaders from buying or selling slaves during their annual meeting in Philadelphia. Abolitionists quoted the Declaration of Independence as they made arguments against slavery in the Pennsylvania Assembly beginning in 1778.4 Two years later, Pennsylvania enacted “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery,” that, although watered down by slave interests, still was the first law in human history enacted by a democratic body to abolish the institution of slavery.5

The first abolitionist society was founded in Philadelphia in 1775. Twelve years later, Syng’s longtime friend, Benjamin Franklin, became president of that group. Perhaps Syng followed Franklin’s lead, evolving from slave owner (as Franklin was when he published Syng’s bounty for Cato in 1748) into an elder statesman arguing the hypocrisy of slavery being embraced in a nation championing universal freedom. Or, he remained more in the camp of George Washington, who famously used a loophole in Pennsylvania’s 1780 anti-slavery law allowing him to bring nine enslaved people to Philadelphia from Virginia to staff the “Presidential House”.6

Syng placed only one classified ad seeking the return of his enslaved craftsman. Does this mean Cato was recaptured before another ad was needed? Or does it mean Syng gave up hope of finding – or at least ever successfully confining – a man so determined to seek freedom? Deduction fades to supposition quickly with one paragraph to source a biography.

Estimates suggest there were nearly half a million enslaved peoples in colonial America by the second half of the eighteenth century.7 Other estimates posit that more than one hundred thousand enslaved people escaped, died, or were killed in the chaotic years before, during, and immediately after the American Revolution. If their names were ever recorded, they appeared only in registries of taxable property or, in the case of Cato and thousands of others, in classified ads or other documents in which they are described only to facilitate their recapture. A few of those brief descriptions, though, open doors to much larger stories.

Syng’s single paragraph leaves many questions unanswered. But one thing is known from this ancient obscure text: in 1748 -- four years prior to the creation of the “Syng inkstand” used at the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution -- a Black man named Cato was forced to wear iron shackles around his ankles and neck to keep him working on the gold and silver treasures attributed to famed craftsman Philip Syng.

Author

Jada Yolich and Network to Freedom

Sources

1 Gary B. Nash, "Slaves and Slaveowners in Colonial Philadelphia," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 30 (April 1973): 236-237. See also: Nash, The Forgotten Fifth: African Americans in the Age of Revolution. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006).

2 B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington, American Population before the Federal Census of 1790, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932), pp. 114-115.

3 Merle Gerald Brouwer, "The Negro as a Slave and as a Free Black in Colonial Pennsylvania," (Ph.D. dissertation, Wayne State University, 1973), p. 17. See also: Edward Raymond Turner, The Negro in Pennsylvania: Slavery-Servitude-Freedom, 1639-1861 (Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association, 1911; reprint ed. New York: Arno Press and the New York Times, 1969), pp. 11-14.

4 Brouwer, "The Negro as a Slave and as a Free Black in Colonial Pennsylvania," (Ph.D. dissertation, Wayne State University, 1973), p. 17.

5 Nash, "Slaves and Slaveowners in Colonial Philadelphia."

6 Erica Armstrong Dunbar, Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (New York: 37INK, 2017).

7 John J. McCusker, ‘Population’, in Historical Statistics of the United States, Earliest Times to the Present, Volume 5: Part E, Governance and International Relations, eds. Susan B. Carter, Scott Sigmund Gartner, Michael R. Haines, Alan L. Olmstead, Richard Sutch, and Gavin Wright (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), Series Eg41, 653.