Last updated: January 7, 2025

Article

Black Education Movement in the 20th Century

This article is part of the series "Desegregation in the Cradle of Liberty." This series explores the Black struggle for equal education in Boston from 1787 to 1976, culminating with protests and violence experienced under forced busing in Boston in the 1970s.

In the 1800s, the Black community of Boston succeeded in integrating the Boston Public Schools. Decades of petitions, protests, speeches, a court case, and other demonstrations culminated with the Massachusetts legislature outlawing public school segregation in 1855. Despite this law and initial success, the schools had once again become racially segregated by the mid-1900s.

As the city expanded, both in population and geographic size, newly arriving immigrant groups established themselves into distinct neighborhoods. In the mid-1900s, racially based housing practices, such as redlining and the construction of public housing allocated by race, also emerged. The growth of both ethnic enclaves and discriminatory housing policies contributed to a racially segregated city. The schools, in turn, became increasingly segregated. Black neighborhoods, in particular, saw their schools suffer more from lack of adequate funding, staff, and other resources.

Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library collection at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections

Beginning of the Black Education Movement

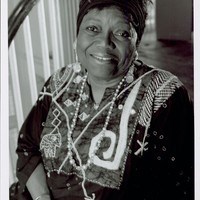

By the early 1950s, the Black community, particularly the mothers, began organizing to combat unequal education in the city. They established the Black Education Movement, a termed coined by one of its founders, Ruth Batson.[1]

Batson, a mother with two students in the Boston Public School system, grew concerned with the issues she saw happening in the schools. She joined a parent advisory council, and, in 1951, ran unsuccessfully for the Boston School Committee.[2] She then turned to the Boston chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for assistance in 1953. At Batson’s urging, the NAACP created a subcommittee on public schools and asked her to serve as its chairperson.

Harvard University Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute

At the same, on a national scale, the NAACP initiated the lawsuits that culminated with the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of the Education that stated:

In the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.[3]

Examining De Facto Segregation

Locally, Batson and the NAACP engaged in a fact-finding effort to document the inferior educational opportunities that Black students faced in the Boston Public Schools. In 1961, they joined with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD) to conduct a survey examining de facto segregation in the Boston Public Schools, meaning though no legislation explicitly segregated the schools, segregation nonetheless existed.[4]

While documenting and collecting information, MCAD set up a meeting with the NAACP and the Superintendent of Boston Public Schools, Frederick Gillis. When the NAACP and MCAD asked for statistics on students in schools, Gillis stated that the Boston School District did not track students by race nor collected information on the race of students.[5] With none of this preliminary information about the student population, the NAACP, MCAD, and parents had to start from scratch in their documentation in order to prove the unequal education experience.

Batson’s and the other parents’ efforts received further help with the release of the Sargent Report in 1962. This official survey of the Boston public schools, commissioned independent of the Black Education Movement, documented the major disrepair of and need for better school buildings in majority Black neighborhoods.

Bringing their own findings and the Sargent Report documentation as proof of de facto segregation, Batson and other leaders, including Paul Parks and Mel King, took their case to the Boston School Committee on June 11, 1963. Their presentation included this list of 14 demands to alleviate the inferior educational opportunities for Black students in the Boston Public Schools:

An immediate public acknowledgement of the existence of de facto segregation in the Boston School System.

An immediate review of the open enrollment plan to allow transfers without present limitations. This plan to be put into operation by school opening in September.

In service training program for principals and teachers in the area of human relations.

The establishing of a liaison between the school administration and colleges so that training programs may be set up for prospective teachers in urban communities.

The assignment of permanent teachers to grades one to three and the reduction of these classes to twenty-five.

The use of books and other visual aids that include illustrations of people of all races.

The establishment of a concentrated developmental reading program in each school in grades one through eight.

The expansion of the school adjustment counselor program in the congested Negro school districts.

The expansion of the vocational guidance program to include grade seven and the selection of qualified un-biased counselors.

The elimination of discrimination in the hiring and the assigning of teachers.

An investigation into reasons as to why Boston has no Negro principal.

A review of the system of intelligence testing.

The adoption in to [sic] of the Sargent report that refers to Roxbury and North Dorchester.

Our most important proposal is as follows: We seek the right to discuss the selection of a new superintendent in detail with Dr. Hunt. [Consultant of the Boston School Committee to choose a new Superintendent] [6]

Despite the evidence presented by Batson and others, the School Committee refused to even acknowledge the existence of de facto segregation in the schools. Louise Day Hicks, a first term committee member, stated:

That is beyond our control. We assigned children to schools nearest to their homes. We reject the charge that this committee has deliberately segregated students in our school system based on race.[7]

As Batson reflected on that meeting:

When I entered the School Committee hearing room, I was taken aback to see the large number of press representatives and TV cameras... I could see that the members of the School Committee were performing for the cameras. I had a funny feeling that this would not be a good night for the NAACP...We were completely unprepared for the level of hostility directed at the NAACP proposal. I had the distinct feeling that we had been ‘set up.’ We had gone into the lion’s den, like lambs being led to the slaughter. These people were not only cold and callous; even worse, they were so uninformed. [8]

Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections

Response to the Boston School Committee

With the School Committee’s refusal to acknowledge the issue of segregation, the NAACP took drastic action. The day after this meeting, three hundred Black and White Bostonians marched to City Hall and began a Lock-Out protest, attempting to prevent the Boston School Committee from entering the building. Rumors of a bomb threat forced everyone to leave the next day.

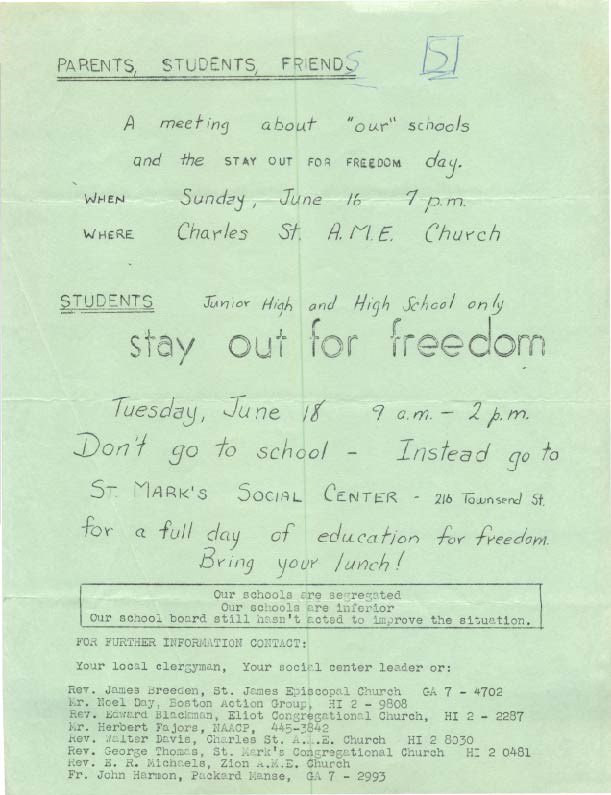

While some activists participated in the Lock-Out, others organized school boycotts, one of the tactics used by equal school rights leaders a century before in the city. This protest on June 18, 1963, called "Stay Out for Freedom," drew more than half of the 5,000 Black students in Boston schools. These first organized boycotts occurred at St. Mark’s Social Center where students listened to speakers such as Rt. Rev. Anson Phelps Stokes, Jr; Northeast Methodist Bishop, Rt. Rev. James K. Matthews, and Celtics legend, Bill Russell.These became known as "Freedom Schools" or "Freedom Workshops," and took place over the next several years.[9]

Northeastern University

Perhaps in response to these demonstrations, the Boston School Committee agreed to meet with the NAACP on August 15. Once again, Hicks and others on the committee refused to acknowledge de facto segregation.[10] As one newspaper reported:

Less than fifteen minutes after a hearing with the NAACP Education Committee began, it was all over. For the third time in two months the school board voted not to discuss de facto school segregation, a majority of the five member board insisting that Boston schools are not segregated either by law or in fact.[11]

Despite the refusal of the Boston School Committee to cooperate with Black Education Movement leaders, the NAACP and Black parents continued their efforts for better educational access in the Boston Public Schools.

Alternative Routes

While appealing to the Boston School Committee to make improvements, Black Education Movement leaders also worked on their own solutions. In 1963, the Higginson School Parents Organization petitioned the principal and stated: "Our children are not inferior, but they have been receiving, in many instances, an inferior education."[12] They presented a list of grievances about student learning conditions, teacher turnover, inadequate books, and lack of support for high achieving students. Furthermore, they stressed the urgency to address these issues as the City began investing in new public schools as part of its Urban Renewal initiatives:

We realize that these problems are long standing and that they are not new, but we feel that with the coming of urban renewal and the announced construction of 3 new elementary schools, it is imperative to focus attention on these concerns now![13]

A few years later in 1966, Ruth Batson organized with surrounding school districts and created the Metropolitain Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO), a voluntary desegregation program that helped place Black students in surrounding suburban schools with openings. Boston students attended schools in Arlington, Braintree, Brookline, Lexington, Lincoln, Newton, and Wellesley.[14] METCO helped hundreds of children find alternatives to the Boston Public School system.

Racial Imbalance Law

After it became clear that the Boston School Committee did not plan to address or acknowledge school segregation despite protests, demonstrations, or committee meetings, Black activists turned their focus to the State House and legislature. Community activist and state representative Royal Bolling introduced the Racial Imbalance Bill to the Massachusetts State Legislature in 1963. This bill called for withholding state funds from racially imbalanced schools, defined as schools with over 50% of school enrollment made up of minority students.[15] The law focused on the racial makeup of students in public schools rather than the issues that created the racial imbalance. After several attempts, it successfully passed into law in August 1965.[16]

Ultimately, the Boston School Committee refused to comply with the mandates of the Racial Imbalance Law and, in turn, lost millions of dollars in funding from the state. By 1971, with Louise Day Hicks off the Boston School Committee and in the United States Congress, the School Committee began to create plans that would comply with the law to restore their funding. Given the delays of the School Committee, however, the State Board of Education announced that it would develop its own plan for the Boston Public Schools.[17]

While the State Board of Education continued to develop its plan for the Boston Public Schools, the Massachusetts Legislature repealed the Racial Imbalance Law in 1974, responding to growing public sentiment. The governor vetoed the repeal. However, he quickly introduced an amendment to the original law that no longer withheld aid from racially imbalanced schools. The amended law passed and which essentially gutted the law.[18]

With this setback, Black Education Movement leaders looked to the courts to improve their children's education. This led to the landmark case of Morgan v. Hennigan.

Overview Timeline Article

Black Struggle for Equal EducationFootnotes

[1] "Introduction," in Ruth Baston in The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 1.

[2] Ruth Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 46.

[3] Ruth Batson, "Thomas Atkins, NAACP General Counsel Justice: The Quest Continues 'The Crisis' December 1980" in The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 46.

Zebulon Vance Miletsky, Before Busing: A History of Boston's Long Black Freedom Struggle, (University of North Carolina Press, 2022), 96.

[4] Ruth Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 68.

[5] Ruth Batson, "MCAD Meets with Superintendent of Boston Public Schools," The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 69.

[6] The Public Education Committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Boston Branch., "Proposals Made to the Boston School Committee.," Stark & Subtle Divisions: A Collaborative History of Segregation in Boston, https://bosdesca.omeka.net/items/show/649.

[7] Zebulon Vance Miletsky, Before Busing: A History of Boston's Long Black Freedom Struggle, (University of North Carolina Press, 2022), 109.

[8] Ruth Batson, "State to School Committee" from Ruth Baston in The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 88.

[9] Zebulon Vance Miletsky, Before Busing: A History of Boston's Long Black Freedom Struggle, (University of North Carolina Press, 2022), 105.

[10] Ruth Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 103.

[11] Ruth Batson, "Walkout Ends School Board Discussions" by John Chaffee, Jr. for the Boston Hearld, August 16, 1963, in The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 105.

[12] Ruth Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 84

[13] Ruth Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 84a.

[14] "The METCO Story" by Ruth Batson in The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 265a.

[15] Ruth Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 83-84.

[16] Jim Vabrel, A People's History of the New Boston, (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 170.

[17] Jim Vabrel, A People's History of the New Boston, (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 172.

[18] Jim Vabrel, A People's History of the New Boston, (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 174.