Last updated: May 5, 2025

Article

Assan through the Ages

US Marine Corps Collection of Still Photos #8813

Assan Beach, the 2,500-yard shoreline stretching between Punta Adilok (Adelup Point) and Punta Assan (Asan Point), which the Marines in World War II called a "pair of devil horns," is a site of rich cultural and historical significance. Best known as the northern beachhead during the Battle of Guam in 1944, it was also home to a thriving CHamoru village and a series of military bases and facilities.

It is a poignant symbol of the island's complex history, blending indigenous CHamoru traditions, wartime struggle, and ongoing military presence. In many ways, the story of Guam can be read through the story of Assan Beach.

Ancient Assan

Between 3100 and 1800 years ago, sea levels around Guam dropped and sandy beaches expanded outward, eventually forming stable coastal plains like what is found at Assan. Over the next 800 years, sea levels only slightly lowered, and the modern coral reefs and ecosystems began to develop.

The earliest occupation of the Assan area dates to between 1000 and 500 BCE (Pre-Latte Period), but the most active occupation occurred between 1100 and 1540 CE (Latte Period). Little is known about Assan during this period, but it was predominantly a fishing village. [1]

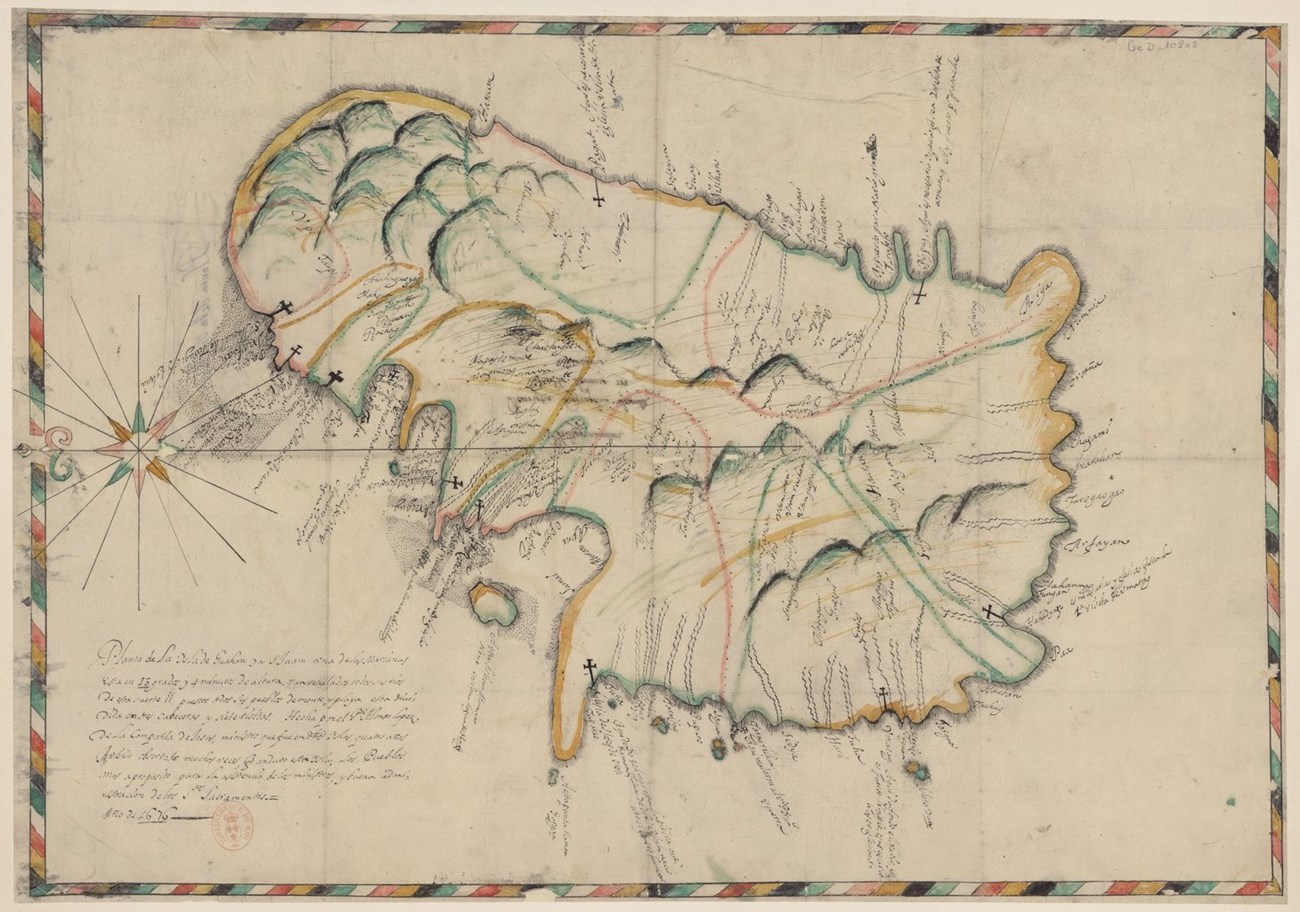

1676: Father Alonzo López's Map

Bibliothèque nationale de France

When the Spanish landed in Guam in 1521, there were approximately 180 villages on the island, ranging in size from just a few homes to Tarragui, which was described as a town of seventy-six houses. The first official mention of Assan comes from a 1676 map drawn by Father Alonzo López, a Jesuit priest who arrived in Guam in 1671. [2]

1680 - 1700: La Reducción

The Spanish did not begin a sustained colonization effort in Guam until the arrival of Father Diego Luis de San Vitores in 1668. The Spanish quickly clashed with the CHamoru, and just a year and a half after arriving, San Vitores had organized a military force in an effort to control the CHamoru. The two sides spent the next thirty years sporadically fighting in what became known as the Spanish-Chamorro Wars.

In 1680, Captain Don Joseph de Quiroga was appointed the new governor of Guam and began a brutal campaign to subjugate the island and the rest of the Marianas. He ordered that any rebellious CHamoru be executed and instituted a policy known as reduccíon. Over the next twenty years, most of Guam’s population was consolidated into six designated villages centered around a Catholic church. This allowed Spanish authorities to ensure that life on Guam revolved around the Catholic faith and Spanish law.

During La Reducción, CHamoru continued to farm at ranches or lanchos in the countryside but returned to town for Mass. The village of Assan most likely fell within the parish of San Ignacio de Hagatña. Residents grew corn, cotton, taro, rice, and sugar cane. [3]

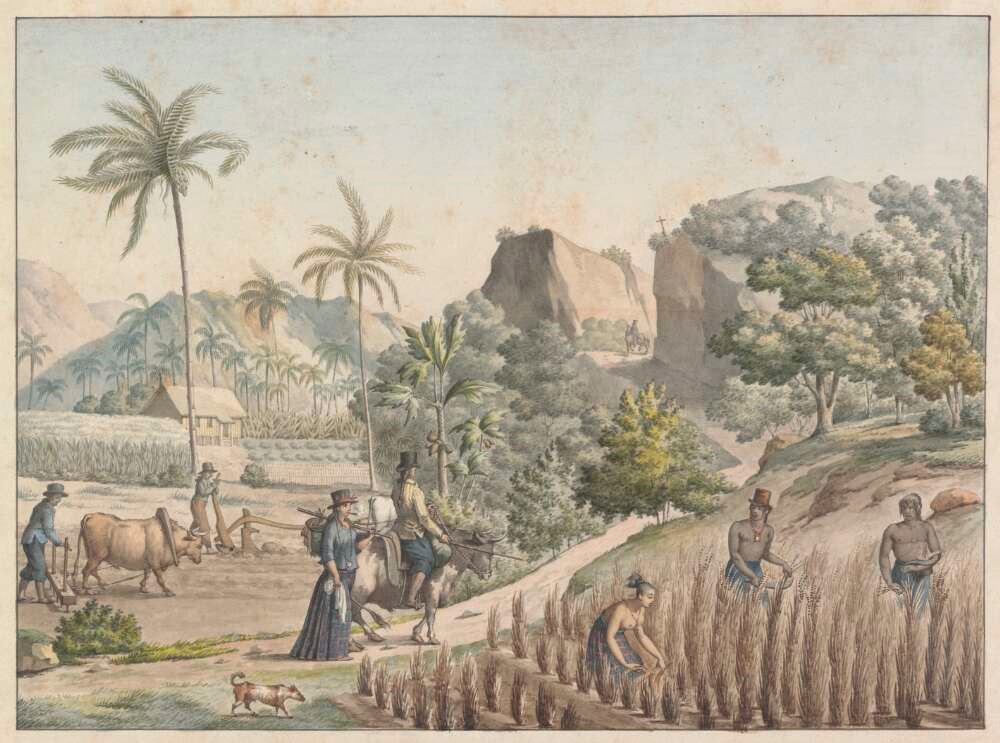

Mid-1700s - Early 1800s: El Camino Royal

National Library of Australia

During the mid-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, the Spanish built a network of roads connecting the island’s villages. The primary road, called El Camino Royal or the Royal Road, passed through Assan on its way from Hagåtña to Umatac. In 1887, Spanish Governor Francisco Olive y García described the road through Assan:

Since all pueblos are located on the coast, they are connected by a road leading from the City [Hagatña] that runs along the shore to Apra Harbor, as far as the Punta Piti landing place … This road, actually a highway, varies in width from four to six meters. … The seven kilometers that have been completed have a very good bed of the cascajo [coral gravel] … Along this road, there are ten solid wooden bridges mounted on supports of mampostería [masonry]. ... A short section of this highway is called the Chorrito, where the cliff is battered by waves.[4]

1892 - 1900: Hansen's Disease Hospital

In 1892, the Spanish established a hospital for Hansen's disease (then called leprosy) at Punta Assan. The hospital was not popular with the CHamoru. While Hansen's disease was viewed as a serious public health risk by Europeans, it didn't carry the same stigma in Guam. CHamoru patients preferred to live at home and be treated by traditional CHamoru healers known as suruhånus and suruhånas.

The hospital's healthier patients took advantage of the confusion between the Spanish governor leaving at the end of the Spanish-American War and the American Naval government being established, and returned home, leaving only the few bedridden and dying patients behind. The hospital was then destroyed by a typhoon in 1900. American authorities did not realize that patients had left the hospital and thought that the disease was eradicated from Guam after the last patient died. It soon reappeared, however, and the United States established a new Hansen’s disease hospital at Tumon Bay. [5]

1901: Protestant Mission Established

In 1901, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent a group of five Congregational missionaries led by Reverend Francis M. Price and his wife Sarah to Guam to convert the mostly Catholic population. The Prices joined a small local Protestant congregation, which had been established by 1899 by Jose and Luis Custino, CHamoru whalers who had converted while living in Hawaii.

The Prices chose Punta Adilok as the site of their mission and school. With the help of the CHamoru Protestants, the Prices led church services and Sunday school, evangelized, taught school, including English classes, and translated the Bible into CHamoru, published in 1908. [6]

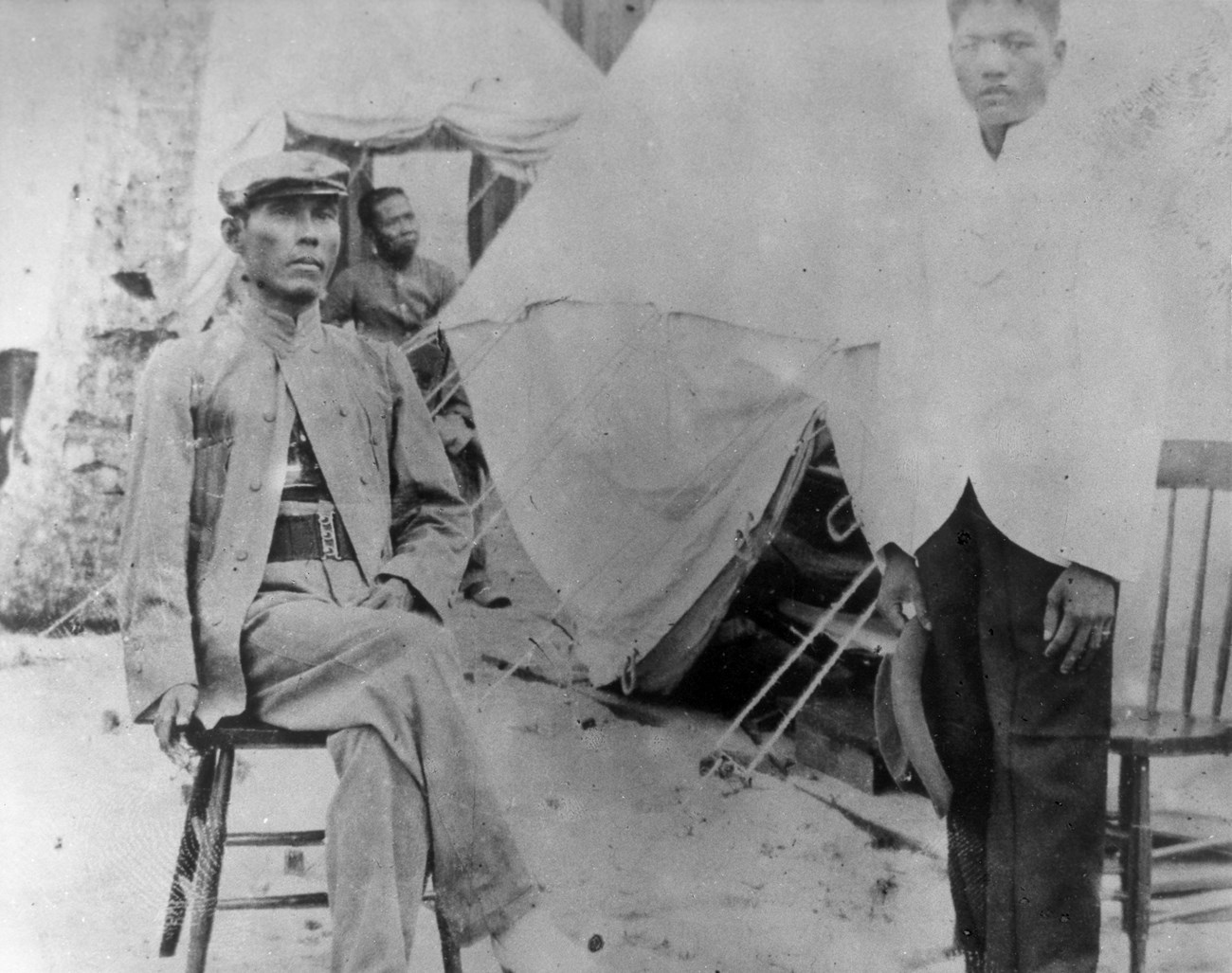

1901 - 1903: Filipino Internment Camp

MARC GC-41-96

Like Guam, the Philippines came under United States control at the end of the Spanish-American War. Filipino nationalists led by Emilio Aguinaldo wanted independence rather than a change in colonial rulers, and from 1898 to 1902, the First Philippine Republic fought a bitter and bloody war for independence.

Aguinaldo was captured in March 1899 and took an oath of allegiance to the United States, but other Filipino leaders refused to do the same. In January 1901, the United States sent forty-eight still defiant Filipino politicians and generals along with fourteen servants to Guam. The most well-known of the prisoners was Apolinario Mabini, Prime Minister of the First Philippine Republic and a chief advisor to Aguinaldo.

The Naval Government set up a prison camp called the Presidio of Asan or Asan Stockade at the site of the former Hansen's disease hospital on Punta Assan. At first, the prisoners were housed in tents but moved to newly constructed barracks in March. By May 1902, an entire complex of buildings, including the prisoners' barracks, commissary, hospital, Marine barracks, officers' quarters, guard house, stables, bath house, and dispensary, had been built.

In July 1902, the United States offered a pardon and amnesty to any prisoner willing to take the oath of allegiance. All but Mabini and General Heneral Ricarte agreed to the terms and were allowed to return to the Philippines in September. The following February, Mabini and Ricarte were finally allowed to return home. [7]

1913 - 1932: Quartermaster Depot

The U.S. Marines established a quartermaster depot, rifle range and barracks at Asan Stockade as early as 1913. A 1916 Navy report describes the stockade as:

At the present time the Presidio of Asan is maintained as a depot for the marine command, and a detail from the various companies is constantly stationed here. In addition, a target range has been laid out to the southward of the road, and a large number of men are generally camped at Asan undergoing instruction on the target range.

Due to cutbacks caused by the Great Depression, the depot, along with most of the military fortifications on the island were dismantled in 1932. [8]

1916: Reservoir and Pump House

Pale' Scott collection, Rlene S. Steffy

In 1916, the U.S. Navy built a reservoir and pump house at Assan Spring. A Navy report from that year described Assan as:

The town of Asan stretches along the road for over one-half mile and is constantly being extended in both directions. The Agana-Piti road is its only street. The town boasts of a church, schoolhouse, and a number of houses of mamposteria.

Most of the residents lived on the island side of the coconut-shaded road that ran through the village. Houses were usually set sixty to eighty feet back from the road, with gardens, coconut groves, and breadfruit and citrus trees. [9]

1917: SMS Cormoran

National Archives 71-CA-149 G-3

On December 13, 1914, the German auxiliary cruiser SMS Cormoran, out of fuel and cut off from Germany by World War I, took refuge from Japanese warships in Guam. Adalbert Zuckschwerdt, the ship's captain, requested enough coal and supplies to reach German East Africa, but Guam's governor refused and instead interned the ship in Apra Harbor.

While technically captives, conditions for the Cormoran's sailors and crew were mild. They continued to live on the Cormoran, but could visit shore, and were an active part of the island's social life. The ship's thirty-five-piece band gave regular performances in the Plaza de España in Hagåtña, and a German officer married an American naval nurse

All that changed on April 7, 1917, when Captain Roy Smith, governor of Guam, received a cable announcing that America had declared war on Germany. Smith immediately demanded the surrender of the Cormoran. Instead of seeing his ship fall into enemy hands, Zuckschwerdt ordered his men to abandon ship, then blew up it up with preprepared explosives.

The Cormoran's crew was imprisoned in Asan Stockade for three weeks, while the officers were held at Camp Barnett on Mount Tenjo. On April 29, the prisoners were sent back to the United States for the rest of the war. [10]

1941: Asan Point Quarry

National Archives 204973456

Concerned about Japanese aggression in the Pacific, Congress authorized $4.7 million for defense projects on Guam. A reef limestone quarry was built at the tip of Punta Assan to provide materials for the projects. The quarry was reestablished by Army Engineers in 1944 during the construction of Harmon Air Force Base. [11]

1941 - 1944: Imperial Japanese Occupation

WAP-040

During the Imperial Japanese occupation of Guam, rice paddies were developed at Assan to feed the Japanese troops. As the occupation dragged on, women, children and the elderly were required to work in the fields. The head of the Minseibu, the Japanese civilian administration, lived at Punta Adilok. [12]

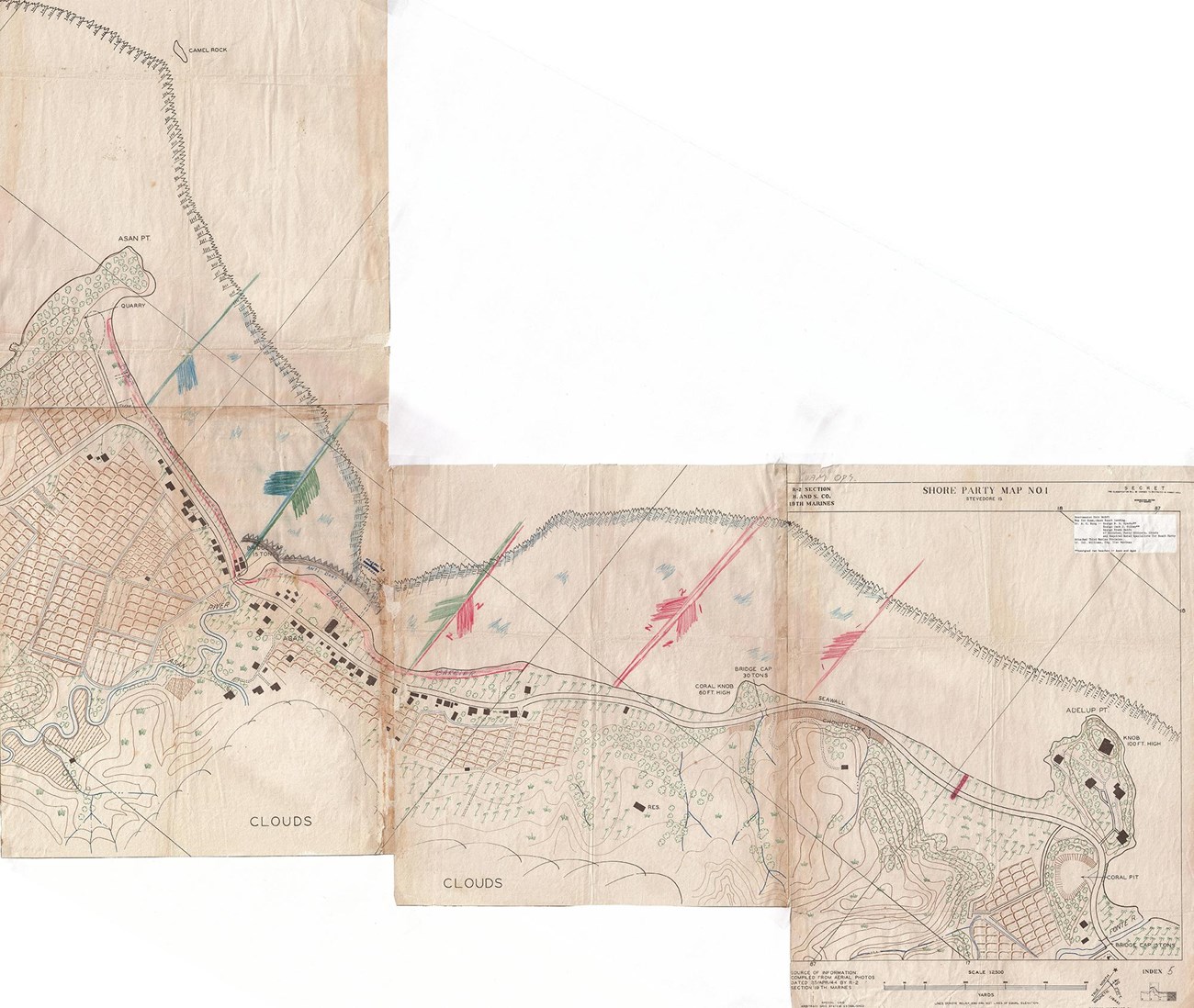

July 1944: Battle of Guam

Guam USMC Photo No. 1-7 From the Frederick R. Findtner Collection (COLL/3890), Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections

Assan Beach was the northernmost of the two landing beaches used by American forces during the Battle of Guam. The beach and surrounding cliffs were heavily bombed in the two-weeks leading up to the attack, completely destroying the village of Assan. Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) blew gaps in the rugged coral reefs offshore to create a route for landing vehicles.

On July 21, 1944—W Day in Guam—the 3rd Marine Division’s first assault wave landed on Assan Beach at 8:29 a.m. The beach had been divided into four sections: Beach Red 1 and Beach Red 2, covered by the 3rd Marines; Beach Green, covered by the 21st Marines; and Beach Blue, covered by the 9th Marines. Imperial Japanese soldiers in well-defended caves on Punta Adilok and Chorrito Ridge put up a strong resistance during the landing, but Bundschu Ridge in the center of Beach Red One and Beach Red Two had the highest casualty rates. 615 men were either killed or wounded during its capture.

It took three days of fierce fighting, but the Marines secured Assan Beach on July 24, 1944. [13]

War in the Pacific National Historical Park

National Archives 80-G-239017

National Archive 127-N-63472

National Archives 127-GR-70-88187

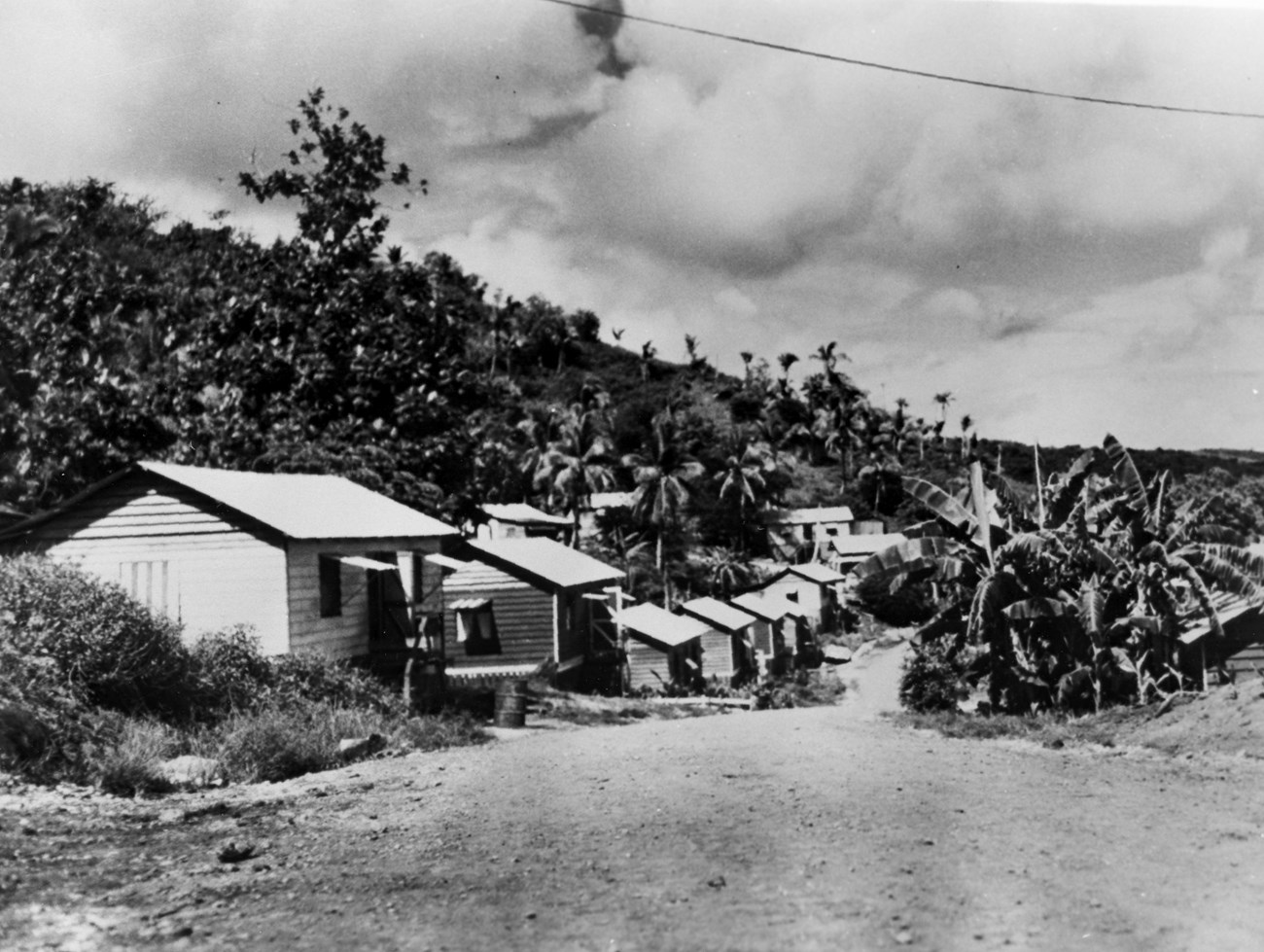

August - December 1944: Assan Rebuilt

WAP-031

Once Guam was secured, the US military encouraged displaced CHamoru to return to their villages and rebuild. Assan, which had been completely destroyed during the Battle of Guam, was rebuilt further inland and to the east of the pre-war village. By November 1944, Assan had grown to 100 homes.

Danny Santos, a retired Marine Colonel who grew up in Assan after the war, recalled his family's new home:

… most of the houses were built independently by people. The original roof was the thatched roof, and then they started changing that out to the tin roof. … It was, to me it was just perfect. … The sides were ... either plywood or bamboo. I think it’s a combination. [Inside, it was] just one open room. Because everything was being made in haste.[14]

1944 - 1947: Camp Asan

National Archives 6682631

Assan Beach and the surrounding plain were used heavily by the military after the Battle of Guam. The area between the Matgue and Assan River served as a refugee camp for displaced CHamoru before a permanent facility was built in Hagåtña. The camp was also used by Filipino laborers helping to build U.S. military bases on the island.

In just sixty days, U.S. Naval Construction Battalions (Seabees) and U.S. Army Engineers bulldozed a four-lane, twelve-mile highway between Hagåtña and Sumai. The highway, which became the current Marine Corps Drive, ran along the seaward edge of Chorrito Cliff, then across the plain and past the western boundary of Assan Village.

National Archives 80-G-346130

Punta Assan, the area that is now Assan Beach Park, was first used as a motor pool, then became the headquarters for the 134th Seabees by early 1946. The Seabees used Camp Asan as a gas station, repair yard, and battalion barracks. It consisted of approximately 40 Quonset huts and outbuildings arranged in rows between Punta Assan and Assan River. Four interconnected Quonset huts located just inland of Marine Drive were used for bowling and other indoor recreation. The southern end of Assan Ridge, on the far side of Marine Corps Drive, was turned into a gasoline storage facility with four tanks, each with a capacity of 10,000 barrels, connected by pipelines to Punta Assan.

National Archives 204971907

The rice paddies along the Assan River became a cemetery for the 632 men of the 3rd Marine Division who died during the Battle of Guam and a separate cemetery for the twenty-five war dogs killed in action. The soldiers were repatriated to the mainland in 1948, and the War Dog Cemetery was moved to Naval Base Guam in 1994. An anti-tank ditch dug in the village was used as a mass grave for Imperial Japanese soldiers. [15]

WAPA Photo Collection Box 11.37

WAPA No. 1780

WAPA No. 1778

US Army Signal Corps Collection of Photographs #272345, Book 1

1948 - 1967: Civil Service Camp/Asan Point Civil Service Community

WAPA No. 78-743-03

By late 1948, the Seabees were gone, and Camp Asan was transformed into a compound for the Navy's civilian employees. The Asan Point Civil Service Community consisted of sixteen two-story barracks, a chapel, club, softball field, tennis courts, basketball court, administration building, mess hall, and fire station. The reef just offshore was dredged to create a swimming area, and an outdoor movie theater was set up near the old Asan Presidio.

On July 4, 1961, Filipino workers at the Civil Service Camp erected the first of many memorials at Assan Beach in honor of Apolinario Mabini who had been imprisoned at Asan Presidio from 1901 to 1903. [16]

1968 - 1972: Advanced Base Naval Hospital

WAPA Photo Collection Box 11.38

During the Vietnam War, injured soldiers were medevacked to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Agana Heights for treatment. The hospital was soon overwhelmed by the number of patients, so the navy converted the former Civil Service Camp at Punta Assan into a self-contained annex known as the Advanced Base Naval Hospital or the Asan Annex. The new annex was staffed with thirty-seven doctors, eighty nurses and nearly 500 other personnel. It could accommodate 1,200 patients. In its first two years, the Asan Annex treated over 17,000 patients. It was closed in 1973 as Vietnam War casualties decreased and the main hospital was once again able to accommodate all of them. [17]

April - August 1975: Operation New Life

War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory, 2013

After the fall of Saigon on April 29, 1975, President Gerald Ford authorized a massive evacuation of South Vietnam called Operation New Life. Once again, Guam served a front-line support role. Twelve refugee camps were quickly opened on the island to house refugees while they waited to be sent to the mainland United States. In just two days, the Naval Construction Forces turned the former Asan Annex hospital into a refugee camp that housed, on average, 10,000 refugees every day.

Not all of the refugees, however, wanted to go to the United States. Some wanted to return to Vietnam. Protests over the slow repatriation process soon broke out, and in July, the military consolidated all the Vietnamese repatriates at Camp Asan "where they could be collectively monitored and policed on military property." At the end of August, things turned violent. Protesters threw rocks and Molotov cocktails and two of the barracks at Camp Asan were burned down.

A repatriation agreement was finally reached in September and the next month 1,546 men, women, and children left Guam for Vietnam. The Assan refugee camp shut down on November 1, 1975, the last of the Operation New Life camps on Guam to close. In total, 111,919 refugees passed through Guam between April and August 1975. [18]

1976: Super Typhoon Pamela

On May 21, 1976, super typhoon Pamela hit Guam, destroying most of the buildings at Punta Assan and Assan Beach except for the fire station from the Civil Service Camp. [19]

1981: Asan Beach Unit Opens

War in the Pacific National Historical Park

Thirteen years after it was officially proposed, War in the Pacific National Historical Park was created on August 18, 1978. Under the guidance of T. Stell Newman, the park's first superintendent, the remains of the hospital, barracks and other buildings were demolished, and picnic shelters and pedestrian paths were built. Approximately 1,000 coconut palm trees were planted at Assan Beach in an effort to recreate how it looked before the Battle of Guam. Asan Beach Unit officially opened in 1981. [20]

1994: Liberators' Memorial

War in the Pacific National Historical Site

As part of the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Guam, the Liberators' Memorial was unveiled at Punta Assan on July 21,1994. This monument honors all of the U.S. servicemen, CHamoru Combat Patrol and Civilian Patrol who participated in the Guam Campaign. [21]

[1] Rlene Santos Steffy and M.J. Tomonari-Tuggle, "A Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project for the Asan Beach Unit and Agat Unit Management Plan War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Territory of Guam" (International Archaeology, LLC, September 2021), 34.

[2] Francis X. Hezel, "Reduction" of the Marianas: Resettlement into Villages under the Spanish (1680–1731) (Northern Marianas Humanities Council, 2021), 14–17; Robert F. Rogers, Destiny's Landfall: A History of Guam, Revised Edition (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2011), 48; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 32–33.

[3] Boyd Dixon et al., "Traditional Land Use and Resistance to Spanish Colonial Entanglement: Archaeological Evidence on Guam," Asian Perspectives 59, no. 1 (2020): 68–70; Evans-Hatch & Associates, Inc, "War in the Pacific National Historic Park: An Administrative History," Park Administrative Histories (National Park Service, 2004), 15- 19; Hezel, "Reduction" of the Marianas, 12–17, 39–42; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 15.

[4] Vida Germano and James Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory, National Park Service" (NPS Pacific West Regional Office, 2013), 23; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 15, 54.

[5] Russell A. Apple, "Guam: Two Invasions and Three Military Occupations" (Mangilao, Guam: Micronesian Area Research Center of the University of Guam, 1980), 85; Connor Murphy, "Leprosy – Hospitals and Colonies," in Guampedia, July 1, 2024; Rogers, Destiny's Landfall, 119; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 40; "Segregation Of Lepers In Guam," The British Medical Journal 1, no. 2162 (1902): 1432–33.

[6] Tanya M. Champaco Mendiola, "Americans Bring Upheaval in Religious Practices," in Guampedia, June 20, 2024; Eric Forbes, "Origin of the CHamoru Protestant Congregation in Guam," in Guampedia, June 20, 2024; Francis M Price, "The Island of Guam and Its People," The Missionary Review of the World, no. 1 (January 1902): 11–19; Rogers, Destiny's Landfall, 125; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 51; "Chamorro Scriptures for the Island of Guam," Bible Society Record 53, no. 7 (July 1908): 101–3.

[7] Apple, "Guam: Two Invasions and Three Military Occupations," 85–86; Josephine Faith Ong, "The Colonial Boundaries of Exilic Discourse: Contextualizing Mabini’s Incarceration in Guåhan" (Los Angles, California, UCLA, 2019), 20–30; Rogers, Destiny's Landfall, 117; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 42–43.

[8] Apple, "Guam: Two Invasions and Three Military Occupations," 86; Leo Babauta, "Asan-Maina (Assan-Ma’ina)," in Guampedia, October 1, 2009; Peggy Nelson, Lisa Duwall, and Laila Tamimi, "Asan and Agat Invasion Beaches: Cultural Landscape Inventory, War in the Pacific National Historical Park, National Park Service" (NPS Pacific West Regional Office: National Park Service, November 26, 2003), 36–37; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 43.

[9] Apple, "Guam: Two Invasions and Three Military Occupations," 77; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 27, 35.

[10] Apple, "Guam: Two Invasions and Three Military Occupations," 86; Nelson, Duwall, and Tamimi, "Asan and Agat Invasion Beaches: Cultural Landscape Inventory," 36; Nathalie Pereda, "The Journey of SMS Cormoran II," in Guampedia, June 29, 2024; Nathalie Pereda, "The SMS Cormoran II Crew – Prisoners of War," in Guampedia, June 29, 2024; Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 126–34; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 43.

[11] Germano and Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory," 16, 46; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 43.

[12] Nelson, Duwall, and Tamimi, "Asan and Agat Invasion Beaches: Cultural Landscape Inventory," 40–45; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 35–36.

[13] Babauta, "Asan-Maina (Assan-Ma’ina)"; Germano and Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory," 33–34; Maj O. R. Lodge, The Recapture of Guam (Headquarters: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, U.S. Marine Corps, 1954), 37–47; Rogers, Destiny's Landfall, 172–73; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 18–19.

[14] Babauta, "Asan-Maina (Assan-Ma’ina)"; Nelson, Duwall, and Tamimi, "Asan and Agat Invasion Beaches: Cultural Landscape Inventory"; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 36–39.

[14] Apple, "Guam: Two Invasions and Three Military Occupations," 88; Germano and Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory," 46–50; Nelson, Duwall, and Tamimi, "Asan and Agat Invasion Beaches: Cultural Landscape Inventory," 54–55; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 45–48.

[16] Germano and Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory," 51; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 48.

[17] Alice Hadley, "US Naval Hospital, Guam 1962-Present," in Guampedia, November 28, 2023; Germano and Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory," 52; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 21, 48.

[18] Jayne Aaron, "Regional Cold War History for Department of Defense Installations in Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands (Legacy 09-454)" (Department of Defense Legacy Program, July 2011), 3-44-3–45; Rogers, Destiny's Landfall, 233; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 21, 51–52.

[19] Evans-Hatch & Associates, Inc. "War in the Pacific National Historic Park: An Administrative History," 61; Germano and Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory," 52.

[20] Evans-Hatch & Associates, Inc. "War in the Pacific National Historic Park: An Administrative History," 97-130; Germano and Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory," 55–56; Santos Steffy and Tomonari-Tuggle, "Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project," 21–22.

[21] Germano and Oelke Farley, "War in the Pacific National Historical Park: Cultural Landscapes Inventory," 56.

Learn More

-

Asan Beach Unit

Asan Beach UnitThe Asan Beach Unit is home to Imperial Japanese fortifications from WWII and memorials to the people who fought to free Guam.

-

The Sinking of the SMS Cormoran

The Sinking of the SMS CormoranThe SMS Cormoran sank in Apra Harbor on April 7, 1917. It was the first American action in World War I

-

Assan Beach during the Battle of Guam

Assan Beach during the Battle of GuamOn the morning of July 21, 1944, the Third Marine Division landed on the beach between Adelup Point and Assan Point.

-

Battle of Guam

Battle of GuamOn July 21, 1944, American forces landed at Guam, kicking off a 21-day fight to retake the island.

-

Liberators' Memorial

Liberators' MemorialThe Liberators' Memorial honors all the U.S. forces involved in the liberation of Guam.

-

Voices of Guåhan Oral History Tour

Voices of Guåhan Oral History TourHear stories about the Battle of Guam from the CHamoru and soldiers who lived through it.

Tags

- war in the pacific national historical park

- war in the pacific national historical site

- guam

- guam history

- assan beach

- military

- us navy

- us marine corps

- military infrastructure

- asian american heritage

- pacific islander

- asian american pacific islander

- aapi history

- aapi heritage

- international relations

- battlefield

- prisoner of war camp

- incarceration

- oceans

- spanish-american war

- vietnam war

- guam during wwii

- wwi

- world war i

- homefront

- wwii

- world war ii

- world war ii history

- world war ii home front

- pacific theater

- war in the pacific

- world war ii in the pacific

- battle of guam

- chamorro

- chamorro people

- chamoru/chamorro

- spanish colonization

- disability history

- hansen’s disease

- leprosy

- missionaries

- philippines

- quarry

- cemetery

- medicine

- military hospital

- nps history

- hospital

- religion