Part of a series of articles titled Commemorating ANILCA at 40.

Article

The Best Job in the World!

The History of Wild and Scenic River Designations in Alaska

Pat Pourchot, Retired, Department of the Interior

Following passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, Pat Pourchot came to Alaska in 1972 with the Department of the Interior to study federal lands for potential inclusion in new national conservation system units. Forty years later he again found himself working for the Department of the Interior as Special Assistant to the Secretary for Alaska Affairs. He retired from that position in March of 2015. He served in state government including eight years (1985-1992) as a legislator in the Alaska State House and State Senate, and as Legislative Director and Commissioner of the Department of Natural Resources for Governor Tony Knowles. His non-profit experience has included management positions with Commonwealth North, the Alaska Federation of Natives, the Alaska Conservation Foundation, Audubon Alaska, and Great Land Trust. He holds a BA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a MPA from Harvard University. He spends much of his spare time chasing rare birds throughout Alaska and North America.

PHOTO COURTESY OF PAT POURCHOT

Casting for grayling while floating down Beaver Creek north of Fairbanks I couldn’t believe how lucky I was. Just a month before, I had arrived in Alaska for the first time and now I was leading an interagency team assessing the suitability of this river for potential inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

I had been working in the Denver regional office of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (BOR) for less than two years—my first job out of college—when the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) passed in December 1971. This landmark legislation settled aboriginal land claims dating back to the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 with the conveyance of about 46 million acres of federal land to Native regional and village corporations. Most of Alaska’s approximately 375 million acres was in federal ownership at that time, but the State of Alaska had been granted approximately 103 million acres under the 1958 Statehood Act, much of which had not yet been conveyed. The pending Native and State conveyances raised a desire on the part of national conservation organizations and congressional leaders to initiate studies of potential new conservation system units. Under Section 17(d)(2) of ANCSA, the Secretary of the Interior was authorized to withdraw up to 80 million acres of federal land for study as potential additions to the national park, wildlife refuge, forest, and wild and scenic rivers systems. Following these withdrawals and study, the Department of the Interior (DOI) was to submit legislative proposals to Congress for consideration. If Congress did not act by December 1978, the withdrawals would lapse, and the land would be available for state and Native selections, or for general land uses under the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

In the spring of 1972, following passage of ANCSA, federal teams were assembled from Alaska and around the country to initiate the conservation system studies: a National Park Service team to study potential new or expanded national parks; a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service team for new or expanded national wildlife refuges; a U.S. Forest Service team for new or expanded national forests; and a BOR team for new wild and scenic rivers. When the Bureau was casting about for volunteers to go to Alaska, I could not raise my hand fast enough, having dreamed of going to Alaska since I was a kid. Although there was initial concern that my low pay grade might not be sufficient to sustain me in Alaska’s high-cost economy, I persevered and joined a five-person team in Anchorage in June 1972.

Our first task was to talk to Alaska land managers, local conservation groups, river user groups, and comb the literature for possible river candidates. This yielded dozens of rivers around the state that had been mentioned as having high value, particularly recreational value. Not surprisingly, many of the rivers were popular fishing, hunting, or floating rivers, many with some road accessibility. With an initial list of 166 rivers, we quickly realized we had more candidates than we could reasonably study and develop into potential legislative proposals. The next order of business was clearly to develop study criteria.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 states that:

certain selected rivers of the Nation which, with their immediate environments, possess outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural or other similar values, shall be preserved in free-flowing condition, and that they and their immediate environments shall be protected for the benefit of present and future generations.

Several rivers in the Act that were initially designated were some of the few U.S. rivers that were still undammed and largely undeveloped. Some segments of these rivers and rivers designated later were relatively short, and most were readily accessible at various locations. This was certainly not the situation in Alaska, where virtually all rivers were not dammed, most flowed dozens if not hundreds of miles through wilderness settings with no streamside developments, most had limited accessibility, and most would certainly qualify for inclusion in the Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

We developed several original criteria for Alaska rivers: (1) rivers should contain at least one, preferably more than one, outstanding value in comparison with other rivers in Alaska; (2) rivers should be selected that represent the different geographic regions and biomes of Alaska; (3) rivers should be of sufficient length to provide significant recreational opportunities or encompass most of the important values of the river; and (4) rivers should be of a length to provide effective management by a federal agency. The last criterion was in recognition that some rivers contained large segments of state or Native lands where long-term management by a federal agency would be difficult or not ensured. Although the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act does provide for the inclusion of state lands and waters, the Alaska National Interest Conservation Lands Act (ANILCA) specifically prevented state lands and waters, and all other non-federal ownerships, from inclusion in federal designations.

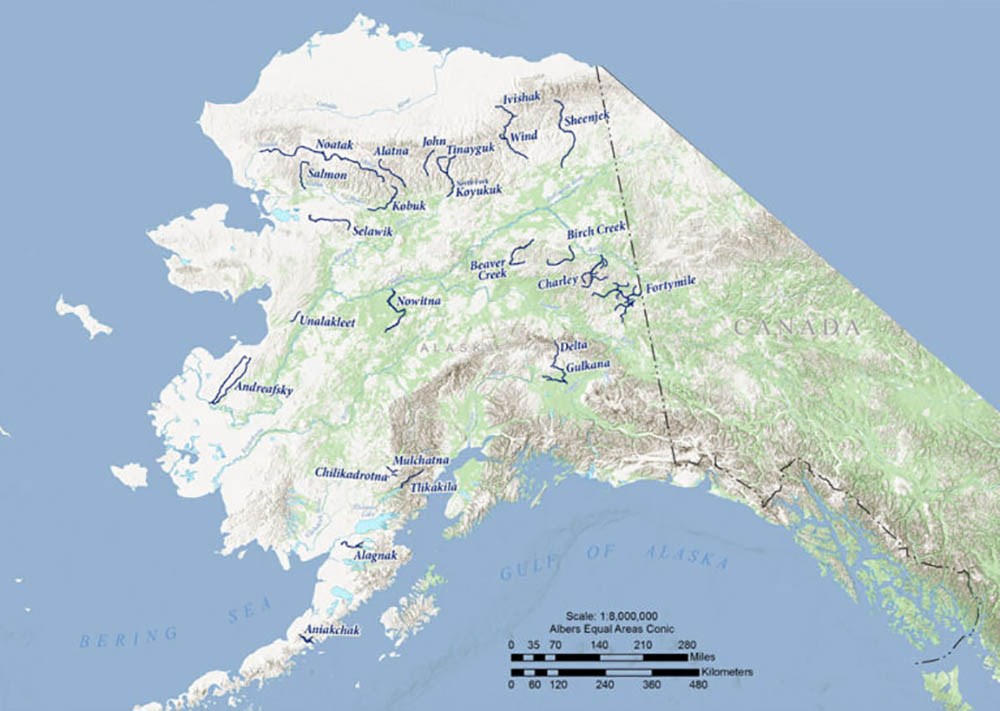

MAP PRODUCED BY THE FAIRBANKS PADDLERS

Based on these criteria and further research and literature review, we reduced our study list to 69 rivers of about 7,000 river miles. We then embarked on a mammoth two-day overflight of a large swath of Alaska from Anchorage to the North Slope. After a very bumpy half day and losing three of five lunches on the plane, we landed in the 90-degree June heat of Fairbanks. After collecting our stomachs, we headed for the Brooks Range and had spectacular views of many of our rivers. Additional overflights and research, consultation with the other federal teams, and further application of our criteria reduced the number of study rivers targeted for more in-depth field investigation.

Then the real fun began. We grouped rivers that might be efficiently inspected together and divided them up among our team. Some rivers were road accessible like Birch Creek and the Gulkana River, but most were reachable only by air. We employed float planes, wheel planes, and helicopters to put-in and take out people, watercraft (canoes and rafts), and gear on the rivers. In those days, we had the ability and luxury to use, when available, fire helicopters on contract with the BLM for the summer. Helicopters provided some unique access opportunities, like into the upper Bremner River (a tributary of the Copper River) and the Salmon River in the Brooks Range that few, if any, recreationists had previously enjoyed.

That first summer we ran river trips on about a dozen rivers with interagency parties. For most trips we invited a representative of the State of Alaska, typically from the Department of Fish and Game, the existing or potential federal land managing agency, a land-owning Native corporation, and others having special knowledge or interest in the river area. Typical inspection teams ranged from four to eight participants. Trip logs and photos were compiled for all inspections—which are still available through the Alaska Resources Library and Information Services and used by recreationists and others today. After the summer season, field notes, and information from participants and existing literature were incorporated into draft river reports describing the resources, important values, and potential for designation of the various rivers.

The initial work and recommendations of the various federal teams were used by the Secretary of the Interior to make final withdrawals of 80 million acres to protect potential additions to the various conservation systems. The work of the federal teams continued for several years to support the first legislative proposal by Interior Secretary Rogers C. B. Morton of approximately 80 million acres of new parks, refuges, forests, and wild and scenic rivers, and then with a change of administrations in 1976, to add additional acreage to the proposals before Congress. In 1980, ANILCA passed. The work of the federal teams laid the groundwork for the creation of over 100 million acres of new or expanded national parks, refuges, and forests.

From 1972 through 1976, I had the opportunity to float over 20 of the “best” rivers throughout Alaska. The field work took me from the shores of the Gulf of Alaska to the Yukon-Tanana Uplands, to the clear lakes and streams of Bristol Bay, to the stark beauty of the Brooks Range. Throughout our field work, we did not experience any injuries, evacuations, animal attacks, or aircraft accidents. Our Bureau of Outdoor Recreation team (later changed to the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service and eventually absorbed into the National Park Service) took special pride in the designation of over 3,200 river miles in 26 new wild and scenic rivers. It was truly the best job I ever had!

Last updated: June 23, 2022