Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 20, Issue 2. Beringia: A Shared Heritage.

Article

Frank Churchill’s 1905 Documentation of the Reindeer Service in Alaska

Varpu Lotvonen and Patrick Plattet, University of Alaska Fairbanks

NPS photo

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) houses a historic collection of photographs from 1905 taken by Special Agent for the Department of the Interior, Frank C. Churchill. These photographs provide a glimpse into the daily lives of reindeer herders in northwest Alaska. The photos show reindeer herders and their families, reindeer herding activities, seasonal camps, and reindeer stations. The collection also documents early territorial schools and government buildings in Alaska as well as maritime life aboard the U.S. Revenue Cutter Bear (Bear). There are a smaller number of photos from East Cape, Chukotka depicting village life scenes, including butchering reindeer and unloading shipping freight.

The photographs that pertain to the U.S. Reindeer Service and herders are of interest because they were taken at a critical period in the Alaska Education and Reindeer Service history. Frank Churchill visited six of fourteen reindeer herding locations, including Teller, Deering, Kivalina, Point Barrow, Gambell, and Golovin. The photographs from his travels provide visual documentation of the territory’s early years of Alaska Native reindeer herding and identify locations of herds in the summer of 1905. By exploring this photographic collection, cross referencing it with Churchill’s final report (1906) and the travel log of the Bear in the summer of 1905 (Log Book of the U.S. Revenue Steamer Bear, July-December 1905), we provide the historical and political context in which the collection was made. In some cases, we identify people, places, and dates in the photographs. We also highlight the challenges Churchill confronted when inspecting the reindeer stations, which ultimately led to his recommendations for new management of the Reindeer Service, as described in the 1906 report.

How Reindeer Herding Got its Start in Alaska

By the time these photos were taken in 1905, reindeer had been herded in Alaska for twelve years. In 1892, domestic reindeer were brought from the Russian Far East to the Seward Peninsula through the efforts of General Agent of Education and Presbyterian Minister Sheldon Jackson. He argued that pastoralism was more valuable than subsistence hunting and that introducing reindeer herding in the new U.S. district of Alaska would improve the economic and societal welfare of Alaska Natives (see Ellanna and Sherrod 2004, Olson 1969, Schneider et al. 2005, Simon 1998, Stern et al. 1980). After unsuccessfully using Chukchi herders to mentor Iñupiat, Sámi herders from Norway were recruited in 1894 and again in 1898 to move to Alaska and teach Alaska Natives herding practices (Fjeld and Muus 2014, Lincoln 2014, Vorren 1994). Reindeer populations increased within the Alaska territory and herds ranged between the Kuskokwim River and Point Barrow (Ellanna and Sherrod 2004, Henkelman and Vitt 1985).

Although reindeer populations were increasing in Alaska, Alaska Native ownership of reindeer was not. By 1904, the vast majority of 10,234 reindeer were owned by missionary societies. General Agent of Education Jackson had appointed missionary societies the dual task of delivering education and managing reindeer operations. The abundance of reindeer owned by missionary societies, however, raised suspicions among U.S. Congress members over the management of the government program. There was Congressional concern that the U.S. Reindeer Service was neither helping the Indigenous Peoples of Alaska nor creating a good return on the government’s financial investment, but only generating income for missionary societies operating in the region (Churchill 1906: 8). The Secretary of the Interior wanted to know whether loaning government reindeer to missions was placing missions in competition with government and Indigenous herding industries (ibid: 115). To answer these questions, and to assess the conditions and management of the territory’s schools, Congress sent Department of the Interior Indian Agent Frank Churchill to Alaska to audit the reindeer stations, record conditions, and document how Alaska Natives were profiting from the industry.

Documenting Reindeer Herding in Alaska Territory

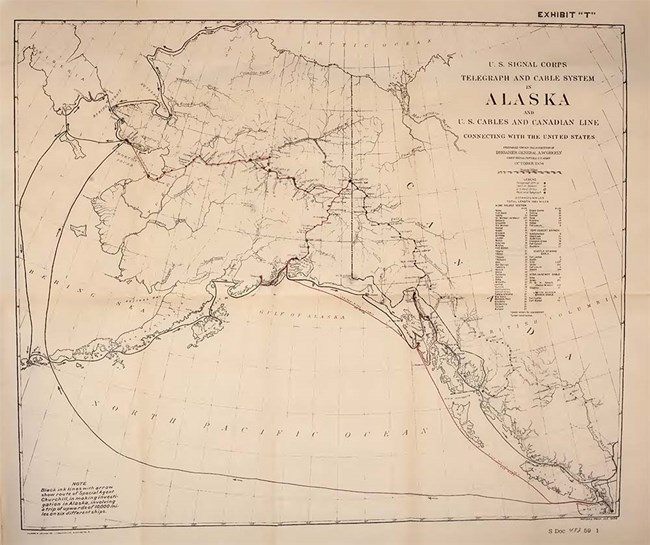

Churchill and his wife Clara traveled to Alaska from Seattle for four months in the summer of 1905. On a Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System map (Figure 1), Churchill drew his maritime route for his audit of the “Reindeer Service in the District of Alaska.” Starting in Seattle, they traveled to Nome, arriving in July where they boarded the Bear. The Bear made a brief stop in Chukotka, then traveled back to Alaska along the Alaska Peninsula, Kotzebue Sound, and as far north as Utqiagvik (Barrow; Lincoln et al. 2019). They visited coastal communities and what were in name reindeer stations, but, in reality, varied widely in terms of infrastructure. Most stations were simply camps and rangeland. On her return journey, the Bear retraced her route, stopping where possible at reindeer locations missed on the outbound trip due to weather. The Churchills remained on the Bear, heading south to Unalaska where they boarded the SS Dora after September 5th. They continued to travel along the Alaska Peninsula before heading back to Seattle through the Alaska panhandle.

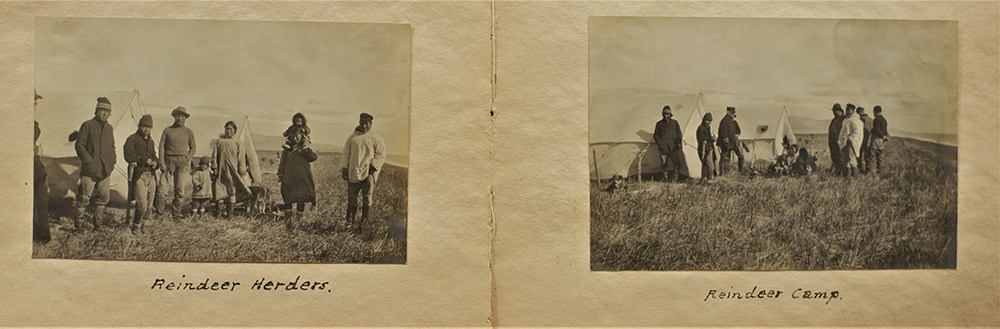

Along the way, through documentation and photography, Churchill tried to quantify herd numbers, record the names and backgrounds of reindeer owners and apprentices, and assess the management of the U.S. Reindeer Service. He met with reindeer agents, teachers, missionaries, and postal service agents, many of whom he and his wife maintained correspondence with beyond their voyage. Some of them shared photographs with the Churchills in the years after their journey north. This communication, particularly with William Thomas Lopp (a teacher and missionary in Wales starting in 1890, and by 1904 the superintendent of government schools and reindeer of the northern district of Alaska), was instrumental in Churchill’s understanding of and position on the future management of reindeer herding. Quotes, documentation, and letters from these settlers were taken as testimony and evidence for Churchill’s Reports on the condition of educational and school service and the management of reindeer service in the District of Alaska, which was delivered to the U.S. Congress in 1906. What is less clear from Churchill’s reports and photographs is how much he spoke directly with herders. He certainly had some level of interaction with them during his visits to reindeer herds and stations as well as aboard the Bear, as the photographs indicate (Figure 2 of Churchill posing in photo with herding families at Kivalina), but unlike the government officials, Alaska Native and Sámi herders are never quoted or credited in his report.

Photo by William Hamilton (Col. Frank C. and Clara G. Churchill Collection, NMAI. AC.058, Alaska [P23369], 1905 July-September, Box 20: 058_020_019).

Churchill’s ethnocentric views, typical of the time, hindered his investigation. He missed important information by neither quoting Alaska Natives directly, nor presenting their knowledge and perspectives. Perhaps Churchill did not feel their words would carry weight with the U.S. Congress members for whom he was writing. Despite Churchill’s colonial biases, the report he delivered to the U.S. Congress was sympathetic to concerns of Indigenous Peoples of Alaska, critical of the role of missionary societies in the reindeer project, and critical of the Bureau of Education’s handling of both education of Alaska Native students and their management of reindeer. His report had immediate impact. It is unclear if Churchill’s investigation led to the resignation of General Agent for Education in Alaska Sheldon Jackson. However, it did result in the complete overhaul of the U.S. Reindeer Service and the Alaska Bureau of Education, which was fulfilled by Jackson’s successor, Lopp. As part of new regulations recommended to Congress in 1906, missionary societies were no longer allowed to profit from reindeer herding and they were removed from both the management of Alaska Native territorial schools and the Reindeer Service.

The Photographic Documentation

The NMAI collection emerges from these interactions and investigations. It is composed of 285 photographs taken by Churchill from June through October 1905. These photos were supplemented by an additional 44 photographic prints taken by William Hamilton of the Bureau of Education, who also traveled on the Bear with the Churchills from July to September 1905, and 71 photographic prints taken by Lopp in 1906 and 1909-1910. They contain images of reindeer herding activities that the Churchills could not experience during their short summer trip.

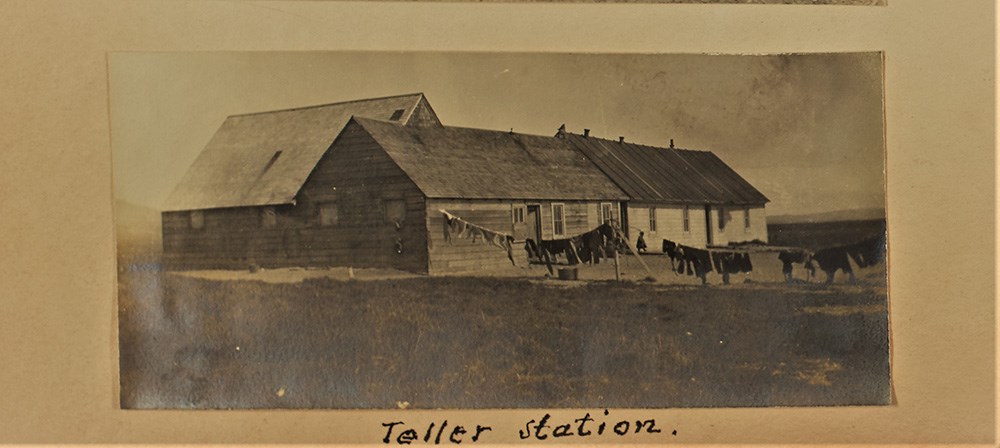

It is very likely that Churchill took the photos in order to jog his memory when he needed to write his report. There are several photographs of government-funded buildings (Figure 3). A major criticism from Congress was that funds allocated to build schools and reindeer stations were not used for those purposes (1906: 65-70). Certainly, the photographs would help Churchill, who had an extraordinary task. Not only was he charged with auditing herd sizes and assessing the management of the Reindeer Service, but also with documenting methods of management and conditions of the territory schools. In 1905, schools in Alaska were segregated as a result of the Nelson Act. Non-Native students were placed in separate schools administered locally, under the jurisdiction of the Governor of Alaska, while Indigenous Alaskan students were placed in federally administered schools, run by the Department of the Interior. Churchill’s written observations and photographs no doubt served as evidence and enabled him to record and remember information in order to make such assessments.

Photo by Frank Churchill (Col. Frank C. and Clara G. Churchill Collection, NMAI. AC.058, Alaska [P23379], 1905 June-October, Box 18:058_018_036).

Clara Churchill used these photographs to create annotated albums. The phrases captioning some of the photos are more from a personal rather than technical perspective, and hence indicate that the albums served as memorabilia. She also gifted albums. During their tour, she gave O. C. Hamlet, Captain of the Bear, an album entitled Reminders of the Cruise of U.S.S. Bear 1905, which is now in the Bancroft Archives, University of California Berkeley Library.

The Journey and its Impact on Churchill’s Thinking

Although Churchill only spent a few weeks visiting the region of Alaska where reindeer were herded, his experiences on the Bear and landing to inspect herds, stations, and schools quickly laid bare fundamental problems with the reindeer project. His experience in Teller, Wales, and Kivalina serves as examples of the challenges he observed.

Teller

In Teller, the first reindeer station he visited, Churchill confronted the challenges of herd management. The Bear arrived on July 19th and left two days later. During that time, despite the opportunity to get close to the reindeer, he lamented that, it was impossible to count them or to tell to whom they belonged (Churchill 1906: 56). In his introductory comments about herding in Alaska, Churchill explained:

The first question to answer is, what is the number of deer in Alaska; the second, where are they located; the third by whom are they owned. Strange as it may appear, these questions can not be answered with exact figures, either by the local custodians in Alaska or by the tables found in the annual report of the Bureau, and it is suspected that accuracy in the deer account has never been looked upon as essential, and even a return of loaned deer appears to have been purely a matter of bookkeeping by the Bureau (ibid: 46-47).

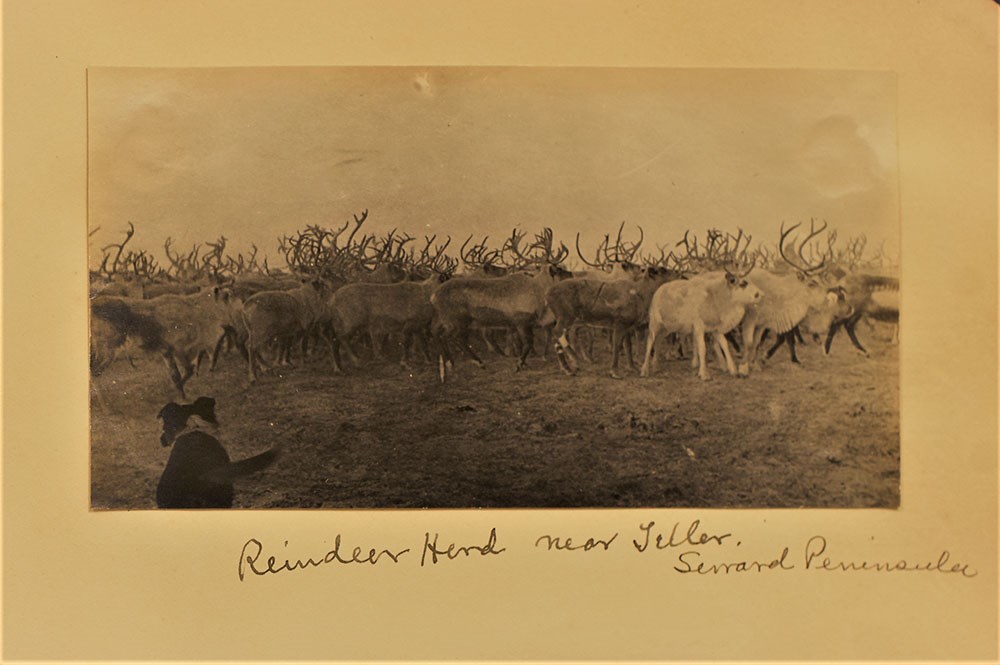

This might indicate that Churchill did not meet with herders at Teller. Had he spoken directly to them, they likely would have been able to quantify their own deer or identify who owned the deer they were herding. It was not until the Bear’s return trip through Teller on August 10th that Churchill acquired reindeer estimates and names of owners from the local reindeer superintendent Rev. T. L. Brevig, who had been out of the territory on Churchill’s first stop in Teller. Brevig, a Norwegian-born missionary and teacher, reported the following numbers, but admitted they were estimates based on a count done the previous year by Lopp. According to Brevig, five Alaska Natives owned reindeer: 15-year-old Ab Likak owned 254, Dun Nak and Se Keog each had 113, Se Raw Look 11, and Koy Look, 10. The Lutheran mission had the largest number at 404, while the government owned 130 (Churchill 1906: 56). Lopp photographed a working dog tending to a herd near Teller (Figure 4), perhaps belonging to the Sámi herder, I. A. Bango, who was paid $500 a year and was fed by the mission in exchange for managing the mission herd.

Photo by W.T. Lopp (Col. Frank C. and Clara G. Churchill Collection, NMAI. AC.058, Alaska [P23364], 1906, 1909-1910, Box 21: 058_021_010).

In addition to understanding firsthand the difficulties of counting and identifying reindeer owners from a large herd, Churchill’s experiences in Teller readily exposed a second major problem of the Reindeer Service: No one understood or agreed on the remuneration of apprentices or who was to pay for their food supplies. Stressing that Brevig had only given out 25 deer to Alaska Natives in the last five years, Churchill criticized:

There seemed to be a lack of knowledge everywhere as to the number of deer that an apprentice would have at the end of his five years’ service; also whether deer turned over to apprentices would come from the mission herd or the Government herd. Then again the matter of who is to furnish the herders with rations does not appear to be settled, and this adds more to the tangle (Churchill 1906: 57).

Teller was the oldest and original reindeer station in Alaska, and as such, Churchill was disappointed that it was not the model for the rest of the industry. He stressed:

Teller is situated on the only harbor in these northern waters; hence ships can safely remain at anchor, and this being the parent station it is only fair to expect that it should have been so conducted that the management should be safely taken as a model in the development of the deer industry (ibid: 57).

Wales

The Bear passed Wales July 21st and again on August 9th during her return trip from Utqiagvik, but was unable to land. For this reason, Churchill relied entirely on Lopp’s knowledge for the documentation of the Wales herd. Churchill wrote:

Mr. W. T. Lopp, now a district superintendent under the Bureau, was a passenger on the ship for several days, and through him I was enabled to obtain the information that would have been sought on shore, and very much more in detail than I could have hoped to secure had I made the landing (ibid: 53).

Lopp was engaged with the reindeer project in Alaska almost from the beginning. Based on numerous quotes, concerns, and testimony from Lopp documented in Churchill’s 1906 report, and based on photos he shared with the Churchills, Lopp had considerably influenced Churchill’s perspectives on both the management of the schools and the Reindeer Service (see also Willis 2006: 291).

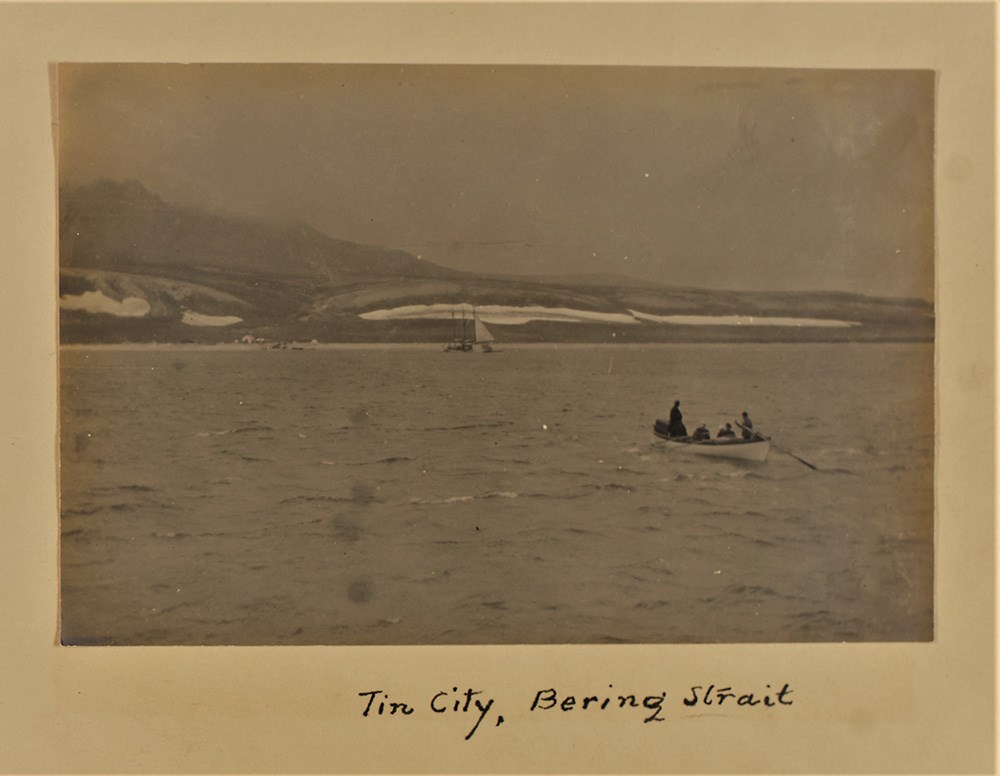

They spent extensive time together. According to the Bear’s logbook, Lopp boarded in Teller on July 19th and he and the commanding officer joined Churchill to inspect the Teller herd the following day. Lopp stayed on the Bear with the Churchills until August 9th when he disembarked at Tin City (southeast of Wales; Figure 5). He also visited and inspected the reindeer stations and herds, when possible, with Churchill throughout Kotzebue Sound and the north slope of Alaska.

Photo by Frank Churchill (Col. Frank C. and Clara G. Churchill Collection, NMAI. AC.058, Alaska [P23379], 1905 June-October, Box 18: 058_018_045).

Amid his discussions with Lopp, Churchill identified unclear record-keeping, a third major problem with the Reindeer Service. Conflicting Bureau of Education reports obscured whether or not Sheldon Jackson gave the Wales Congregationalist Mission 118 reindeer as a gift or a loan. In his Twelfth Annual Report on Introduction of Domestic Reindeer into Alaska, Jackson indicates that ... [t]his mission has long since returned to the Bureau of Education 118 deer ... that were loaned to them (Jackson 1903: 13, see also Churchill 1906: 53). Conversely, Lopp, who was the teacher and reindeer superintendent in Wales at the time, insisted that these animals were a gift to the mission. Churchill writes,:

Mr. Lopp said, however, that there was never any uncertainty about the question, and that the deer were actually given to the mission, and that he never knew why they were carried on the books as a loan (Churchill 1906: 54).

Of concern to Churchill and the U.S. Congress was that the missionary societies were making considerable money from a government loan without repayment. These loans carried no interest; 100 deer were loaned to missions, and usually five years later, 100 deer were returned. In some cases, the missions were asked to provision apprentices, but agreements were loosely formed. Protective of government resources and the appearance of fairness, Churchill wrote:

The mixing up of interests to the extent that we find here must be regarded as unwise in the long run, as it tends to conflict of authority and to stir up jealousies and antagonisms that were better avoided (ibid: 54).

This example of unequal distribution of government resources shaped the conclusions of Churchill’s report, whereby he advised the U.S. Congress to eliminate loans of reindeer to missionary societies and to remove them from reindeer management.

Kivalina

The Bear travelled along the Seward Peninsula, stopping at the Deering reindeer station and Kotzebue. On the 26th of July, the Bear landed at Kivalina, called Corwin Lagoon at the time. There, Churchill met with and photographed two herders and their families, Electoona who has 172 deer, and Otpella with 48 deer (ibid: 52; Figure 6). According to earlier Bureau reports, Electoona and Otpella had affiliations with the Kotzebue herd but had moved their deer to Kivalina either temporarily (for summer rangeland) or permanently, perhaps due to competing access to rangeland near Kotzebue. Countering the narrative that Jackson promoted in Bureau of Education reports that schools and herds were only successful when managed by the missionary societies, Electoona and Otpella were successful independent herders despite the fact that there was neither Bureau of Education infrastructure, nor missions in the region to “manage” their herds. Because he was neither an employee of the Bureau of Education nor a proponent of missionary societies, Churchill’s direct observations offered Congress a fresh perspective, which complicated and often contradicted the scenarios that Jackson had been presenting to the government for over ten years.

Photo by Frank Churchill (Col. Frank C. and Clara G. Churchill Collection, NMAI. AC.058, Alaska [P23368], 1905 August-October, Box 19: 058_019_005).

Churchill’s experience in Alaska and direct observations of reindeer also identified several instances of what Churchill considered wasteful uses of government funds. Churchill wrote:

The Department authorized, April 18, 1905, the expenditure of $5,000 to establish a schoolhouse and dwelling at Kivalina… After a personal inspection nothing was seen nor heard to warrant the establishment of a school at this place. There is no village, and the only natives found were Electoona…and Otpella…with their families on the beach… It is possible that the establishment of the school may result in a few Eskimo families building huts in the vicinity, but it is hardly probable, for a long time at least (1906: 52-53).

Churchill’s oversight sought to ensure that the herding situation and local educational needs matched the Bureau’s policies and justified government expenditures. In the case of Kivalina, Churchill struggled to understand why the Bureau allocated funds to build a school and pay a teacher when he could find no pupils and could see no work being done. He wrote:

Carrying out the declared policy of the Bureau of arbitrarily establishing deer stations so as to make a complete chain on the Arctic coast, must be the only excuse for putting in this school (ibid: 52-53).

Under Jackson, the Bureau sought to build numerous reindeer stations regardless of need or suitable rangeland. Churchill’s statement reveals a second more implicit policy, whereby the Bureau of Education established reindeer stations and schools in the same locations. This policy continued as reindeer herding was introduced through western Alaska and in the Alaska Peninsula and Iliamna regions such that in some cases there were schools built where no children lived and reindeer stations built near inadequate rangelands (see Lincoln 2014).

Conclusion

Though Churchill had never been to Alaska before 1905, he had years of experience as a U.S. government agent negotiating with Native North American Tribes. He understood treaty relationships between the U.S. and Tribal governments and recognized the legal obligations to Indigenous Peoples residing in the United States. With this background, and his protection of government resources, Churchill identified essential problems with the Reindeer Service, such as inadequate bookkeeping and misinformed policies. His experience in Alaska helped him understand the concerns of Alaska Natives. He wrote:

Herding requires a tenacity of purpose wholly new, and even if the natives took willingly to the new order of things, where is the food for himself and family coming from if he spends his time watching deer? The answer comes at once. They must be fed by those who put them into their new environment (Churchill 1906: 62).

He even confronted Jackson’s most significant tenet that Alaska Natives should turn away from hunting to become “civilized” herders. Churchill writes:

as for supplanting the present principal occupation of Eskimo in deriving the most of his living from hunting and fishing, nobody believes it possible or desirable. Fish, blubber, oil, and wild fowl are necessary articles of food in the Arctic (ibid: 36).

Despite identifying problems and limits of the herding industry, Churchill supported its continuation, stating:

I beg leave to refer to the general trend of this report, throughout which the general policy of getting the animals into the hands of the natives as fast as their capacity for caring for them can be developed has been made prominent (ibid: 63).

The Churchill report and associated archives add to this important facet of Alaska’s history. It offers alternative and critical perspectives of government programs, their employees, and missionaries. Such investigations not only add to our collective understanding of history, but also, investigating these archival sources illuminates the history of land use from which the National Park Service and other government agencies define their current management policies. Perhaps even more importantly, these investigations shed light on the historical engagements between Alaska Natives and U.S. government administrators that continue to frame contemporary relationships today.

References

Churchill, F. C. 1906.

Reports on the condition of educational and school service and the management of Reindeer Service in the District of Alaska. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Ellanna, L. J. and G. K. Sherrod. 2004.

From Hunters to Herders: The Transformation of Earth, Society, and Heaven Among the Inupiat of Beringia. Edited by Rachel Mason. Anchorage: National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office.

Fjeld, F. and N. Muus. 2014.

The Sami Reindeer People of Alaska: Stories and Photos from the Reindeer Project. Duluth, Minnesota: Faith Fjeld and Nathan Muus.

Henkelman, J. W. and K. H. Vitt. 1985.

Harmonious to Dwell: The History of the Alaska Moravian Church, 1885–1985. Bethel, Alaska: Moravian Seminary & Archives.

Jackson, S. 1903.

Twelfth annual report on introduction of domestic reindeer into Alaska, 1902. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Lincoln, A. 2014.

The history of reindeer herding on the Alaska Peninsula, 1905–1950. Alaska Journal of Anthropology 12(2): 23-45.

Lincoln, A., V. Lotvonen, and P. Plattet. 2019.

Reminders of the Cruise of the U.S.S. Bear: An illustrated chronology of Frank Churchill’s 1905 journey to Alaska and Siberia, Poster presented at the 46th Annual Meeting of the Alaska Anthropological Association, Nome, Alaska, February 27–March 2, 2019.

Olson, D. F. 1969.

Alaska Reindeer Herdsmen: A Study of Native Management in Transition. Institute of Social, Economic and Government Research, University of Alaska.

Schneider, W., K. Kielland, and G. Finstad. 2005.

Factors in the adaptation of reindeer herders to caribou on the Seward Peninsula, Alaska. Arctic Anthropology 42(2): 36-49.

Simon, J. K. 1998.

Twentieth Century Iñupiaq Eskimo Reindeer Herding on Northern Seward Peninsula, Alaska. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Stern, R., E. L. Arobio, L. L. Naylor, and W. C. Thomas. 1980.

Eskimos, Reindeer, and Land. School of Agriculture and Land Resources Management, Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Vorren, Ø. 1994.

Saami, Reindeer, and Gold in Alaska: The Emigration of Saami from Norway to Alaska. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press.

Willis, R. 2006.

A new game in the North: Alaska Native reindeer herding, 1890-1940. The Western Historical Quarterly 37(3): 277-301.

Archives

Reminders of the Cruise of U.S.S. Bear 1905. To Capt. O. C. Hamlet From Mr. & Mrs. Frank C. Churchill. Bancroft Library Archives, Bancroft BANC PIC 1905.13607–ALB.

Log Book of the U.S. Revenue Steamer Bear, July-December 1905, National Archives Catalog, Available at: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6919240 (accessed 1 May 2021)

Col. Frank C. and Clara G. Churchill Collection, National Museum of the American Indian. AC.058, Alaska [P23379, P23368, P23369, P23364], Box 18-21, 1905, 1906, 1909-1910.

Last updated: December 15, 2021