Last updated: July 15, 2025

Article

African Americans and the Hot Springs Baths

Government Free Bathhouse

The federal government began providing free baths for poor people after 1878 by building a frame bathhouse over the popular “mud hole” spring, and continued to provide free baths for indigents until 1956. During the early 1880s people who could afford to pay also bathed there, believing the water to be superior. Everyone—black, white, male, or female—had equal access to this bathhouse, but because the spring flow there was not very strong, two or three hour waits for a bath were common. The government erected a new brick free bathhouse on this site in 1891. Remodeled in 1898 on a sexually and racially segregated plan, the bathhouse nevertheless gave indigent black and white bathers equal access to the facilities. In 1921 a new government free bathhouse opened its doors to the public. It, too, was segregated by sex and race with separate facilities for black women, white women, black men, and white men. After 1956, indigent black bathers were sent to the Pythian Hotel Bathhouse and the National Baptist Sanitarium and Bathhouse.

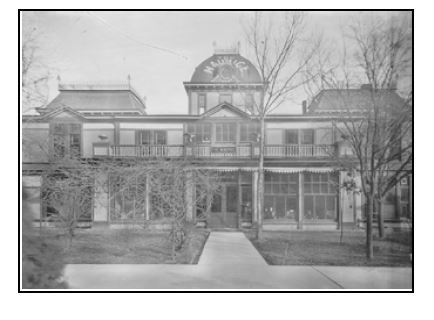

African Americans and the Early Pay Bathhouse

Little is known about African American bathing during the 1860s and 1870s. In the 1880s black patrons could buy bath tickets at the Ozark Bathhouse, the Independent Bathhouse, and possibly the Rammelsberg Bathhouse on Bathhouse Row, but they were not allowed to bathe during the hours considered optimum by prescribing physicians, particularly from 10 a.m. to 12 noon. Since black communities were at some distance from Bathhouse Row, physicians agreed that walking home in the cool early morning or late afternoon hours after bathing might be a health risk; even so, for several years nothing was done to remedy the situation. An African American man named A. C. Page took over the Independent Bathhouse lease in 1890, operating it less than a year as an exclusively black bathhouse. William G. Maurice then purchased it, remodeled it, and reopened it as the Maurice Bathhouse, serving white patrons only.

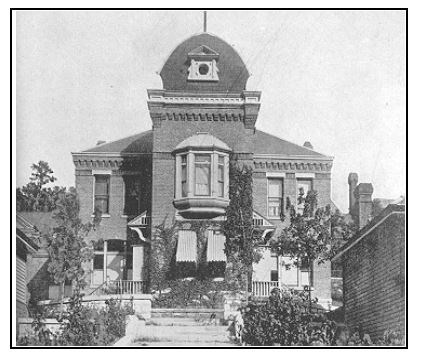

Crystal Bathhouse

The Crystal Bathhouse was the first to be built for the exclusive use of African Americans. Designed by architect John McCaslin (who also designed the Maurice Bathhouse and the Great Northern Hotel and Baths), it opened in 1904. The Crystal had a good location at 415 Malvern Avenue at the edge of the African American business district. Owned by M. H. Jodd and A. R. Aldrich, white men, the bathhouse with rooms to rent above was managed by R. L. Torrence. In 1908 the lease was transferred to the Knights of Pythias of North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia, under local management by Dr. Claude M. Wade and John T. T. Warren. The Crystal burned in the 1913 fire, which destroyed 50 city blocks along Malvern, Central and Ouachita Avenues. From that time until the Pythian Bathhouse opened, blacks wanting baths had to claim to be indigent and bathe at the Government Free Bathhouse.

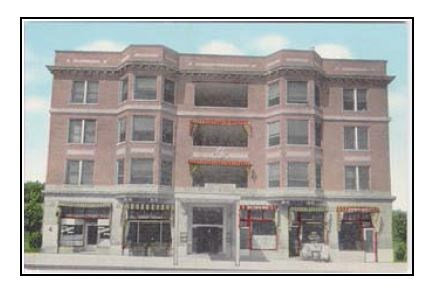

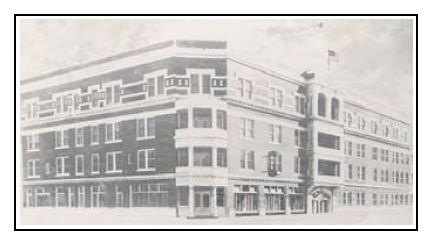

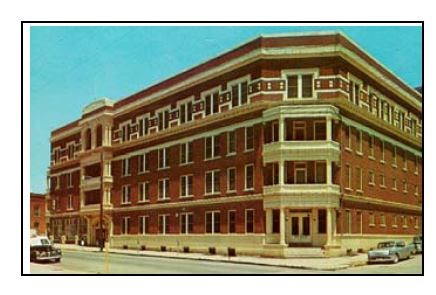

Pythian Bathhouse and Sanitarium

The Pythian, named for its proprietors, the Knights of Pythias, stood on the site of the former Crystal Bathhouse. African American W. T. Bailey, head of the architecture department of the Tuskeegee Institute in Alabama, designed the building. The hotel opened on December 27, 1914 under the management of J. T. T. Warren. The bathhouse provided bathing services half price for members of the Knights of Pythias insurance organization. The building was remodeled and enlarged to add a sick ward and more rooms and to relocate the bathhouse, rising from a two-story to a four-story building. When the Woodmen of the Union Building closed in 1935, its hospital was relocated to the fourth floor of the Pythian under the direction on Dr. John E. Eve. The Pythian operated successfully until desegregation in 1965 opened the rest of the town’s bathhouses for black patrons. After operating part time for a number of years, the building closed in 1974. The Austin Hotel parking lot is now located on the site.

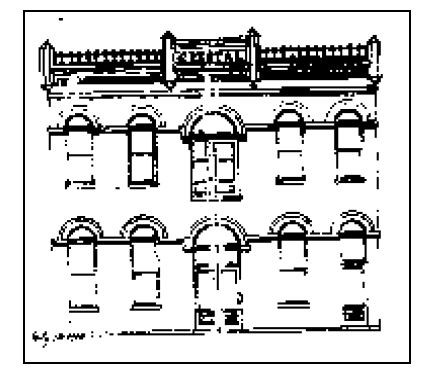

Woodmen of the Union Building

Tuskegee Institute architect W. T. Bailey designed the Woodmen of the Union Building in 1922; it was financed by the fraternal insurance company, Woodmen of the Union under the leadership of John L. Webb. This impressive building complex featured first-class hotel accommodations and a 2000 -seat theater, along with a 600 capacity meeting auditorium, gymnasium, print shop, beauty parlor, and newsstand. Count Basie, Pegleg Bates, and Joe Louis were only a few of the top name entertainers, sports celebrities and political figures who came during its prime. Blacks could now choose between two bathhouses.

The building was also the primary health care facility for the African American community, housing a hospital, doctor and dental office as well as a bathhouse, vital services since other medical facilities in the city were for whites only. The hospital provided treatment to members free of charge and also treated black indigent patients referred from the Government Free Bathhouse and other healthcare facilities in the city.

National Baptist Hotel and Sanitorium

The African American National Baptist Convention bought the Woodmen of the Union Building in 1948 and remodeled it over the next two years. The management continued the tradition of the Woodmen of the Union by providing a hospital, nurses’ training school, and doctors’ offices with the hot springs baths still an important part of the health care. It also hosted the annual National Baptist Association Convention until the early 1980s when the organization bought another hotel in Nashville, Tennessee.

It closed in 1983. Alroy Puckett, manager from 1968 until closing, remarked, “It’s a small price to pay for integration. If that is what is killing us then let it go on.”

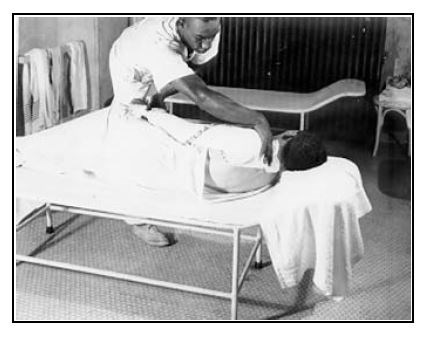

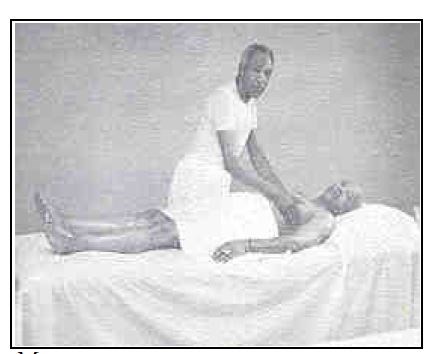

Bathhouse Employees

Aside from management, the mainstay of the bath industry from early times was the bath attendant and until the 1980s, most bath attendants were African American. Massage services were added in the bathhouses in the 1890s and later chiropodists. Take a look at the duties involved.

Bath Attendants

Bath attendants are referred to as early as 1875. By the early 1900s, the government listed specific duties for bath attendants which included cleaning the bathing areas, helping invalids, laundering patients’ bath robes, and rubbing mercury; they were expected to furnish all supplies needed to perform these duties.

In 1910 the government employed a doctor as medical director of the bathhouses. Regulations changed to specify that the bath attendants “shall not be required to handle helpless invalids, rub mercury, furnish mops, brooms, or cleaning materials; furnish or launder towels, mitts, sheets, or robes; pay for the services of the porter or perform work which properly belongs to him; or incur any expense whatsoever incident to the operation of the house not specifically authorized.” Rules and regulations Governing Bath Attendants in the Pay Bathhouses Receiving Hot Water from the Hot Springs on the Hot Springs Reservation, 1914. Attendants were still required to clean bathhouse areas assigned by the manager.

The medical director began classes in 1910 to instruct the bath attendants on physiology, hygiene, and first aid. They had to pass a written test, and their work had to be observed and approved in order to keep their employment. “They are all Negroes.... Major Harry Hallock, Medical Director

Massage

Those giving massage were originally called “masseur” if male and “masseuse” if female. In the 1960s both began to be called massage therapists. The earliest records available show that one of the first African American masseurs was James Truman. We know that he was working as a masseur in the Arlington Hotel Bathhouse in 1922. One of the first African American masseuses was Estella Hughey, who worked at the Majestic Hotel Bathhouse in 1926. Her husband, Earl C. Hughey, began working as a masseur in 1929.

Other Positions

Male and female mercury rubbers were on staff, generally in combination with another duty. The mercury rubber applied an ointment containing mercury to the bather as directed by the patient's physician to treat syphilis. It was applied using a glove or brush. Mercury was the primary treatment for syphilis from the 1500s until the advent of penicillin in the 1940s.

A porter would take male bathers and a maid would take female bathers from the lobby to the dressing room, helping the bather undress and don the bath sheet. These employees also cleaned the dressing rooms as well as the public areas of the building. Today they are called dressing room attendants.

Management employees tended to reflect the race of the clientele—African American in the Crystal, Pythian, Woodmen of the Union and National Baptist.

As mentioned in this article, African Americans could work in bathhouses but not use them before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Here are some photographs of buildings that were owned and operated by the African American community.