Part of a series of articles titled The History of Slavery in St. Louis.

Article

A Society Built Upon Enslaved Labor

Missouri Historical Society

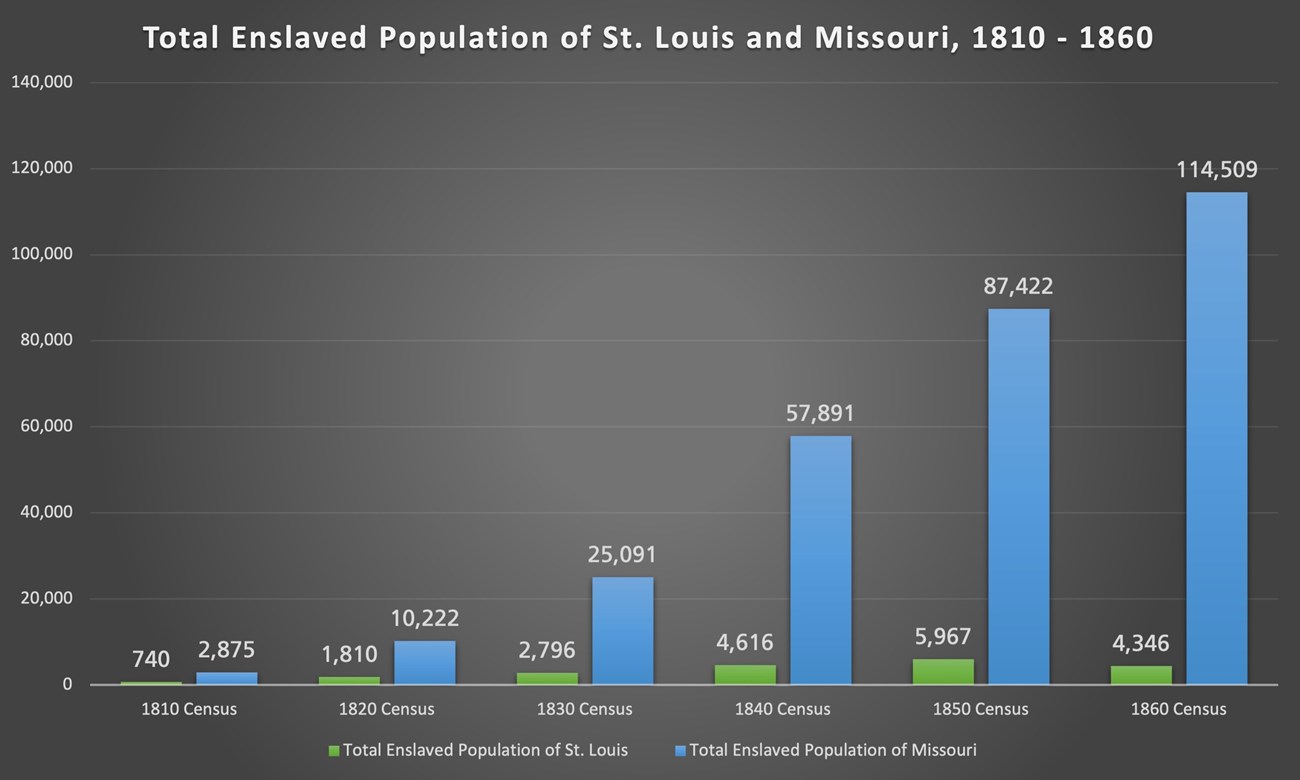

The institution of slavery existed in St. Louis for 100 years. French settlers Pierre Laclede, Auguste Chouteau, and their followers founded St. Louis in 1764. These White settlers relied upon enslaved Black people to build streets, construct Catholic churchs, work on farms, serve as nurses, and attend to household chores. Some of the city’s enslaved population had been born in Africa and forcibly brought to North America through the Middle Passage. Roughly thirty percent of St. Louis’s residents were enslaved during the city’s early colonial period.

As St. Louis grew to become a large urban city in the 1800s, enslaved people worked a wide range of occupations. In addition to farming, they worked in domestic roles such as laundry and cleaning, at construction sites and restaurants, on the docks of the Mississippi River, and on steamboats. Enslaved people endured horrible abuse, including working long hours without pay in terrible conditions and whippings by their enslavers. They also experienced the pain of permanent family separations through sales at auctions. Black abolitionist William Wells Brown, who had been enslaved in St. Louis as a teenager and young adult, later remarked that “no part of our slave-holding country is more noted for the barbarity of its inhabitants than St. Louis.”

NPS

The Language of Slavery

In recent years, scholars and activists have argued for more accurate language when describing the experiences of people who were enslaved. Debates about appropriate language continue today. This virtual exhibit aims to use person-centered language that emphasizes the humanity of the people who suffered under slavery.

-

Using “enslaved people” rather than “slave” emphasizes how a person was forced to perform their labor under the threat of violence and against their will. The term “slave” implies that a person was not fully human but instead a form of property.

-

Using “enslaver” instead “slaveholder” or “master” recognizes that enslaving another human as property was a deliberate, active choice rather than something natural or normal.

-

Using “freedom seeker” rather than “fugitive” highlights how enslaved people who attempted to run away were not criminals, but people who actively sought the freedom of themselves and their loved ones from slavery.

Smithsonian Institute

Slavery and Freedom: William Wells Brown

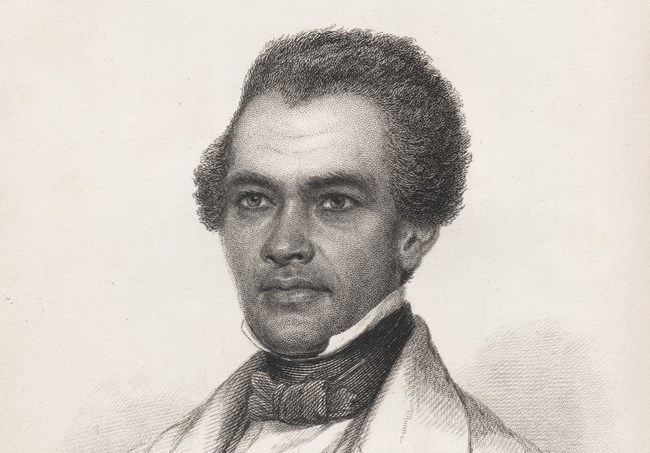

William Wells Brown (c. 1814–1884) was enslaved in St. Louis for eight years. As a teenager, Brown was “hired out” by his enslaver to work various jobs for other people in St. Louis. Around 1827 he briefly worked at the printing office of The St. Louis Observer, a newspaper operated by journalist Elijah Lovejoy. Becoming gradually opposed to slavery, Lovejoy would later die at the hands of a proslavery mob in Alton, Illinois, for his views. Brown also worked on numerous steamboats along the Mississippi River during this time. He worked as a butler and waiter on these boats, learning what life was like in both the free and slave states. These travels inspired Brown to seek freedom. At age 19, Brown ran away from a steamboat that had docked in Cincinnati, Ohio. He successfully evaded capture in part because Ohio outlawed slavery.

Brown went on to become a famous abolitionist (a person who called for the immediate end of slavery), writer, and speaker. His 1847 autobiography, Narrative of William W. Brown, made Brown famous in America and Europe. In addition to being a talented lecturer, Brown was the first known Black American to publish a novel (Clotel, 1853) and the first to write a play (The Escape, 1858). He also helped recruit Black soldiers to serve in the U.S. Army during the Civil War in the 1860s. Today, Brown remains a celebrated figure in American literary history.

Gateway Arch National Park/NPS

Last updated: November 2, 2023