Last updated: July 9, 2024

Article

50 Nifty Finds #42: Model Rangers

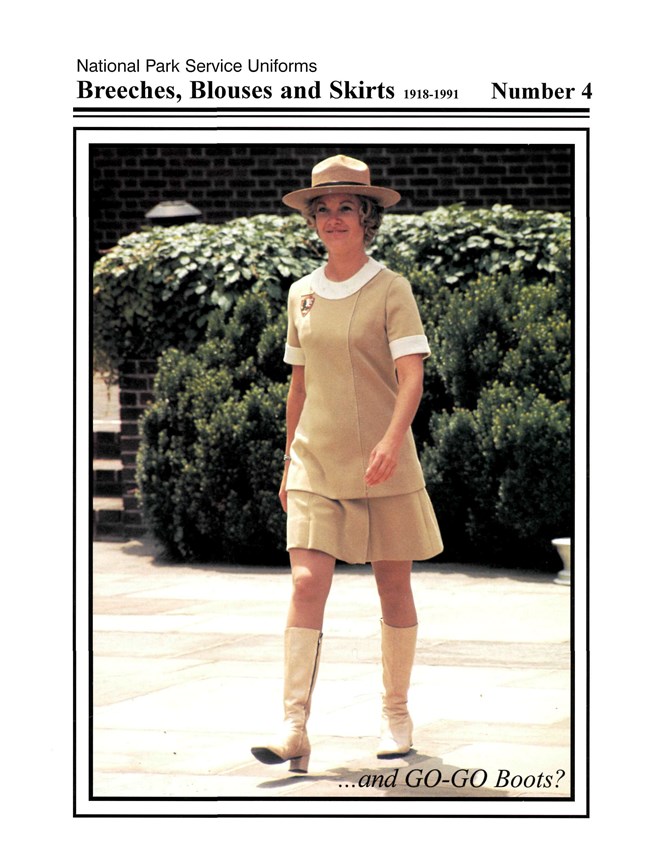

The beige women’s wardrobe is one of the most misunderstood National Park Service (NPS) uniforms. It’s also the uniform that usually gets the most attention—despite being worn for only three years. Many incorrectly believe it dates to the 1960s and featured miniskirts and go-go boots. The fact that it is the one least like the standard green ranger uniform wasn’t an accident. Designed with “apparel graphics” in mind from a color chart under consideration for NPS signs, it’s not surprising that it wasn’t functional for many jobs held by NPS women.

An Attempt at Unity

On July 28, 1967, management consultant James M. Kittleman submitted a report to NPS Director George B. Hartzog Jr, noting,

Field organization units of maintenance, interpretation, natural science, research, and personnel do not have the status and prestige of the traditional ranger but are equally as important to the success of the total operation.

Attempting to address this issue and improve NPS esprit de corps, in February 1969 Hartzog appointed a committee to recommend “a uniform which could be used by all employees without distinction to his employment status or capacity.” The committee was chaired by Midwest Regional Director Fred Fagergren and included Robert Gibbs, Robert Moore, and Hazel Oliff. It’s not known if there were other members, and Oliff may have been the only woman of the group. She worked for the NPS from 1957 to 1976 as a secretary. Given that she was Hartzog’s secretary at the time, it’s reasonable to assume that he was well informed about the direction the committee’s recommendations were taking.

The committee submitted its written recommendations to the director on June 26, 1969, as new uniform standards. On July 2, Hartzog approved and distributed them to all employees. Although today you might expect that statements such as “the purpose of these recommendations is to unify and bring about uniformity that shall apply to all National Park Service employees except US Park Police” to mean that men and women wore the same uniform, that wasn’t the case.

The new NPS green women’s uniforms replaced the 1962 uniform that had been based on American Airline stewardess uniforms and described by some as “early orthopedic” or “old maid dowdy.” Superintendents, regional directors, or directors designated who would wear the new uniform. The dress uniform consisted of:

- Dress: wool-blend, knit, yoked shift with stand-up collar, a long back zipper, and the NPS arrowhead shoulder patch; worn with gold name plate; $18/25

- Jacket: blazer-type acrylic, double-knit, double-breasted, V-neck jacket without collar, with gold “ladies’ size” NPS buttons and an NPS arrowhead shoulder patch; worn with gold name plate; about $25/30

- Vest: acrylic, double-knit, V-neck vest with gold NPS buttons down the front and on pockets; worn with gold name plate; about $15

- Blouse: white Bermuda or Peter Pan collar, roll-up sleeves or sleeveless, made from Dacron polyester cotton blend; cost $5/$3.50

- Skirt: A-line skirt with a small waistband and no pleats made from a wool blend or an acrylic wool jersey double-knit fabric; no price listed

- Scarf: silk or nylon with small arrowhead insignia interweave or matched motif, in various sizes for wear as a muffler, scarf, handkerchief or in hair

- Hat: pillbox made of material to match jacket, vest, skirt, and dress; similar to United Airlines stewardess style 1969

- Summer straw hat: straw with small brim, gross-grained and stitched cordovan-colored plastic band insert

The jacket, vest, and skirt could be of combination wool jersey or cotton provided the material matched in color and weight. The 1969 uniform standards also included drawings of appropriate skirt length. The descriptions accompanying them showed mini, midi, and regular skirt lengths. The mini length was “to show young knees and slim legs—wonderful look for sports” and the midi length “for after dark and perfect for wearing at home or to parties.” Neither were acceptable for the NPS uniform. At no more than two inches above the middle of the knee, the “regular short skirt is for everyone! Practical for busy lives and so right looking.” Miniskirts, which were mid-thigh or higher and shorter than the mini length described above, and boots were not part of this uniform.

Two types of shoes were available—leather pumps or wedge-heeled Oxfords. The skirt and blouse option resembles a uniform worn by women like Bera Arnn working as a park naturalist in Washington, DC, in the late 1950s.

In addition, a field uniform eliminated the earlier dress and replaced the skirt with culottes or slacks, provided they were made of the same material as the rest of the uniform. The culottes were plain or had a three-button placket closing and cost about $6. The slacks were also a polyester-cotton blend with a French waistband and a side zipper. Each pair cost $5. A work uniform was described only as a “proper, green-colored dress or jumper.”

Optional items for the uniform included an all-weather coat, green cardigan sweater, white cloth or cordovan leather or plastic gloves, and a white cloth or cordovan leather or plastic purse. No uniform suppliers were listed, but some of the drawings included in the standards suggest that most of the uniform items came from mail order catalogs.

The 1969 uniform standards were to come into effect on January 1, 1971. Ironically, three goals of the uniform guidelines—minimize changing uniforms, “avoid abrupt and wholesale change, stabilize and traditionalize the uniform,” and bring about one uniform with a minimum of options—do not appear to have applied to the women’s uniform. Although the standards recommend that proposed changes be carried out before the 1971 deadline, it’s unlikely that the committee envisioned the radical changes that came next.

Apparel Graphics

No records have been found documenting women’s reactions to the 1969 women’s uniform standards or why it wasn’t implemented as approved. Instead, a women’s uniform committee was established. An article in the April 2, 1970, NPS Newsletter reports that the committee was established in response to the June 1969 standards “directive that the women’s uniform be materially changed.” Yet the 1969 standards don’t say that. When he approved the 1969 uniform standards, Hartzog noted to all employees that “the women’s uniform has been materially changed” [emphasis added].

The challenges facing the committee were described as “identifying the needs of park women, choosing a designer, finding a manufacturer willing to such a relatively small group, pricing within the limited uniform allowance, and outfitting the many women stationed all over the country.” It seems that rather than implementing the 1969 uniform design, the committee started over.

Despite its focus on women’s uniforms, the committee was chaired by NPS Chief of Operations Robert Gibbs. He brought on Carole Scanlon, an interpreter at Independence National Historical Park, to represent women in the field and to “coordinate their activities.” Scanlon ran with the assignment and is credited with spearheading the process and the results. Gibbs’ involvement is largely unspecified, although a short biography of him is published along with the April 2, 1970, NPS Newsletter article discussing the process used to create the uniform. Scanlon noted,

Our first impulse was to hire a “name” designer, as many of the airlines had done. But we needed more than just a design—we wanted complete coordination of all facets of our front line staff. We had to have someone who was as interested in function as fashion—and who would listen to the unique wants and needs of our field personnel.

Scanlon reached out to Mary Joan Glynn, vice president of Doyle Dane Berbach, Inc. in New York City, one of the largest advertising agencies in the United States at that time. Glynn, head of “product styling,” worked on previous campaigns for airlines and a car rental company. In the 1960s she introduced the knit dress to American Airlines flight attendants, revolutionizing their uniforms. Irene Beckman, a product development associate and head of fashion styling at the company, assisted Glynn.

As Glynn and Beckman learned about the NPS mission, they and Scanlon spoke with dozens of women across the NPS about their jobs and uniform preferences. A four-hour meeting on the uniform was held with women of National Capital Parks (NCP). The committee sent the 250 uniformed women in the NPS a questionaire requesting personal statistics and size information. Many sent in suggestions with their answers. Men’s opinions were also solicited. Russell E. Dickenson, general superintendent of NCP (and future NPS director) stated, “This is great! In the past the difficulty with ladies in uniform was that they tried to adapt from men’s materials and styles. I think that the women’s uniforms need to be ‘jazzed up.’ I’d even like to see them in entirely different colors. Some colors just aren’t feminine.”

Dickenson’s comment may have sparked the change from the basic NPS colors of white, cordovan, green, gray, and gold established in the 1969 uniform regulations, but that can’t be proven. Unbelievably, Allen Fields, civil engineer at the Eastern Service Center and a member of the uniform committee, gave Glynn a chart of colors being considered for use on park signs and posters to use when selecting a color scheme. In the end, she selected a “colorful wardrobe in shades of beige, orange, and white” over the previous uniform of “murky green shades.”

Although marketed to NPS women for its flexibility that gave “far more freedom than in the regulations of the past,” Glynn’s creation had many similarities with the approved 1969 uniform. The flexibility, interchangeability, color coordination, and different uniforms for dress, field, and work were all part of the 1969 regulations; even the double-knit polyester, culottes, slacks, and arrowhead scarf were conceived before Glynn was hired. The biggest differences were the colors, hat style, and the uniforms for administrative staff and volunteers.

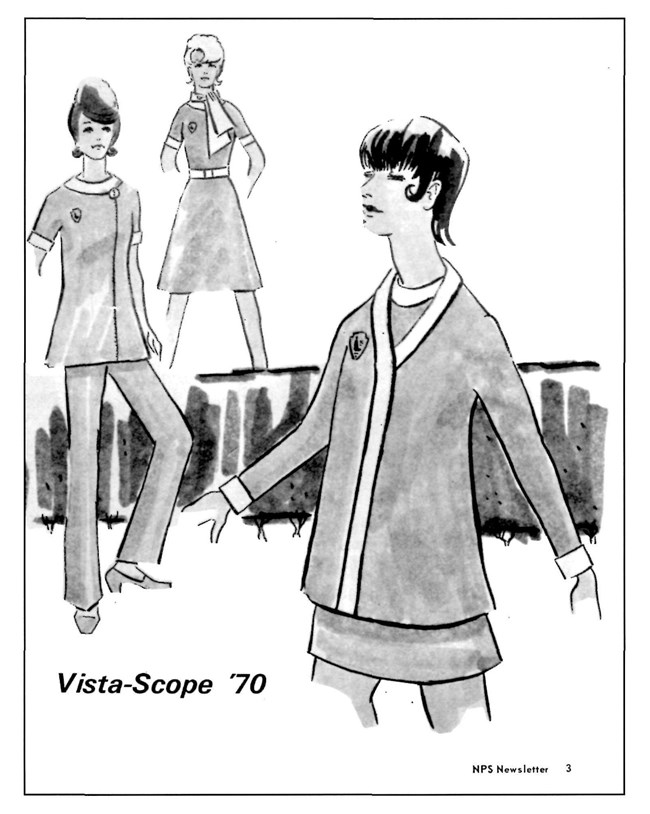

Vista-Scope '70

Although Glynn was known for creating full “packages” of products for all aspects of a company’s visual representations, and despite the committee’s desire for “complete coordination,” the women’s uniform was developed in a vacuum separate from the men’s uniform or the overall NPS brand image (except, of course, for matching the signs and posters!). The uniforms were referred to initially by the inscrutable “Vista-Scope ’70” name. It was later explained,

What we wear—the way we look—is an integral part of the total environment. In this era of concern with our surroundings, it is important to consider the visual impact of our apparel graphics. The National Park Service people have a very special stake in their visibility—for they must be a part of their environment yet be immediately identified by the visitors to the parks. Vista-Scope '70 is designed to achieve this objective. The color graphics have been drawn from the environmental roots of our natural heritage—from the colors of the earth and sand, from the air and snow, and the golden sun.

It’s unclear why the NPS green uniform color was not part of the color palette for the natural environment. These “apparel graphics” only applied to the women’s uniform, which would have certainly blunted their impact for the NPS. It’s worth noting, however, that the 1972 optional men’s uniform featured brown slacks, camel or green blazers, and gold shirts. Unfortunately, the details of its development are unknown. A connection to Vista-Scope ’70 cannot be made without further evidence.

Fashion Shows

On February 25, 1970, Glynn presented design sketches, fabric colors, and swatches to the uniform committee. Its members enthusiastically endorsed them, and sample garments were ordered to illustrate the design to Director Hartzog.

About nine months after Hartzog approved the 1969 uniform regulations, the new women’s uniform was presented to him and the full uniform committee in a private fashion show on March 20, 1970. Scanlon modelled the various uniform options with Glynn’s narration. The unveiling was described in the NPS Newsletter as “an immediate success.” The article goes on,

As [Scanlon] modeled each outfit, the women gasped in delight and even the men beamed happily. A few secretaries in “civies” quickly exclaimed that they too would like to wear the uniform. Former rangers who had been opposed to ladies adopting the campaign hat were satisfied with the new variation, which looked equally attractive on several different women. Most important, everyone was impressed with the total coordination of the outfits, in terms of both color and design.

Creative license was probably taken with this description as suggested by photographs from the day, which only show one woman, Betty Gentry, present besides Glynn and Scanlon.The article notes that Hartzog was “so pleased with the results that he gave his immediate approval to the whole project.” He reportedly said, “It’s beautiful, simply beautiful. This will be an important addition to our overall public image and particularly to the many lovely ladies who work in our park system.”

The uniform was unveiled to a broader audience a few months later in a fashion show in the rose garden at Independence National Historical Park on June 27, 1970. In addition to Scanlon, the NPS women modeling the various uniform components were:

- Elaine Hounsell, ranger-naturalist at Lake Mead National Recreation Area

- Ellen Lang, park technician (and later superintendent) at Sitka National Historical Park

- Louise Boggs, maintenance worker at Independence NHP

- Marion Riggs (now Durham), archeologist at Walnut Canyon National Monument

- Ingar Garrison, wife of Lon Garrison, then regional director of the Northeast Region

- Helen Hartzog, Director Hartzog’s wife

Helen Hartzog was invited to participate by Lon Garrison and Chester A. Brooke, superintendent at Independence. The letter, which is also part of the NPS History Collection, asked her to model the "hostess apron" and suggested that if she was unavailable then perhaps her daughter would do it. Members of the government, fashion leaders, and news media were asked to join the "fashion preview." Director Hartzog served as the master of ceremonies for the event.

Asked how she was selected for the modeling job, Durham replied that her best guess was it was because she and the other women had sent in suggestions to improve the uniform. She recalled,

We get the announcement that the new design has gone through all the review process, and [what it looks like]. I thought, “Oh, yikes.” Well, the next thing I know, my superintendent gets a notice from the regional office, which has got the notice from the Washington office, that the archeologist at Walnut Canyon has been designated to appear in the fashion show that’s going to show this new uniform. We were shipped to New York City and put in a hotel and shuttled to and from this fashion house, where they fitted us all up with all these pieces. I was just assigned to model the culottes and the little tunic top. All of us are just kind of looking at each other and thinking, “Oh my God, we should be home.” So, we show up at Philadelphia with all these pieces from the fashion shop and the fashion people. Nobody’s done anything about a hat [for me]. There’s a guy standing next to me from Philadelphia, and he’s got on his straw [hat]. I said, “What size is your straw?” He said, “Seven.” I said, “Can I borrow it for this thing?” And I took it and I put it on. No approval. Nobody had said diddly do. I just did it.

Several hundred people attended the event including NPS management and field staff, the Junior League of Philadelphia, and a few tourists. The NPS History Collection includes a silent film of the event.

After the fashion show, Durham was selected to travel to the Southwest Regional Office and the parks in the NPS Southwest Region to model the uniform. She recalled,

My superintendent came storming into my office and said, “They want you now to have a car and drive all over the Southwest.” I went, what?! He had got some kind of an order to get me a government car, and I was to tour every park in the Southwest Region and model all of the pieces that were within this uniform selection. I mean, I was dumbfounded. I couldn’t believe it! The fashion company had my measurements. They made up a set of every single one of those pieces, and they sent it to me. We worked out a travel schedule. I went to every single Southwest park. Every single one of them. And it was uniform reaction. The women who were in ranger positions were delighted to have pants. The women who were in secretarial positions, their main question was, “Do we have to wear the hat?” I answered the question day after day after day.

As Durham had the only set of uniforms, local NPS women of similar size were recruited to model some of the uniforms with her.

Just when she thought it was over and returned to Walnut Canyon, Durham was told she needed to model the uniform for President Lyndon B. Johnson.

I bundled everything up into a garment bag and made arrangements. Flew to Austin. Got a rental car, drove out to the ranch. I’m so surprised at how casual it was. When I got there, I had to ford a little river to get to the gate. And that’s all it was. It was just a gate, like a ranch gate. There was a guy standing there. He said, “Yes?” And I told him. And he said, “Oh, yes, we’re expecting you.” Opened the gate. Said, “Go down here. Turn right. Drive down here a mile. There are two little houses on your left. Stop at the one where the president and Mrs. Johnson are sitting on the porch.

She remembers changing in one of the small bedrooms in the house. “I changed clothes and walked out, showed him what it looked like. Went back in, put on another piece, came back out.” Neither the President nor First Lady reacted each time she came out and did “a little twirl.” When she finished, the President asked about reactions to the uniform.

I said, “It’s better than what we have, but it’s not what we want.” He said, “What do you want?” I said, “We would prefer, because we are their peers, to have the same uniform as the men who do the same job.” He had no response. I didn’t expect him to. His question was far more serious than I anticipated. I didn’t anticipate he would ask me a question, to tell you the truth. So, my response to him was pretty off, right from my heart. Because I really felt, just from having spent all that time in all those pieces, that it was going to be a real disaster. That’s kind of why I answered the way that I did, that it was better than what we had, but it wasn’t what we wanted.

Worrying that she would miss her flight, Durham wore the slacks and tunic to the airport. Seeing her in uniform a child asked her, “Are you an elevator operator or a stewardess?”

The Women's Wardrobe

Director Hartzog approved the new uniform in a memo to “The Ladies of the National Park Service” on August 11, 1970. Attached to the memo were Guidelines for the New National Park Ladies’ Wardrobe. The fact that it was referred to as a wardrobe rather than a uniform is telling. He also reported on the preview event that, “The men, including superintendents, field directors, and many guests thought they were most attractive. The ladies seemed to like them too!”

The basic uniform elements were:

- dress

- jacket

- tunic

- culottes

- slacks

- zip-up smock

- work smock

- pop-on

- hat

- scarf

- scarf hat

The August 1970 memo also included additional specifications for “outerwear and special duty wear.” These items, based on climate and duty, were to be agreed upon by the employee and the supervisor. Interestingly these all relied on “off-the-rack” clothes available from the 1970 Fall–Winter Sears and Roebuck catalog. These optional uniform elements were:

- White or brown ski jacket

- White or dark brown cardigan sweater

- Camel tan jeans with flared legs

- Wheat beige cotton twill jeans

- Light-brown or gold umbrella

- White or beige short gloves for dress wear

- Dark-brown gloves with a lining for warmth

- Beige neutral tone panty hose or stockings

- Beige (not bone) to light-brown shoes

- Beige to brown leather boots

- Clear vinyl rain hat cover to fit hat size

- Beige to light-brown handbag (leather in winter, straw or fabric in summer)

- Sunglasses with simple frames

Specifications for jewelry were simple pearl or gold earrings and personal rings. “Judicious use of the American Indian craftwork in silver and turquoise” was also recommended. A new gold name tag was to be positioned just above the National Park Service patch. Specifications for makeup and hair noted,

With personal appearance an important part of our environmental personal graphics, we recommend simplicity and a healthy natural look in all makeup and hair styling.

The wardrobe guidelines didn’t mention the lifeguard uniform, although a butternut-beige one-piece swimsuit with terry jacket was mentioned as part of Vista-Scope ’70. The nurses uniform is also left out of these guidelines because they remained the traditional white nurse’s uniform dress, cap, stockings, and shoes with a white or blue cardigan sweater and blue nurses cape.

Hartzog wrote to the field that he “would like to see all the uniforms in the parks by the end of November.” The women were to get their orders to Hart Shaffner and Marx, the uniform manufacturer, by September 18. The $125 uniform allowance was to offset costs, but the women had to personally pre-pay with their orders. The uniform shipments were delayed, however, and women didn’t receive them until January 1971.

Ironing Out the Wrinkles

On December 4, 1970, an advance release of the new uniform standards was sent to all field directors. This was an interim draft, as it contains sections where new language has been pasted over what would have been an earlier version. The cover memo sent with release also stated, “A notable change in this release is the inclusion of a weight chart based on body frame and height which should provide a more workable guideline than the chart originally proposed,” suggesting that NPS women were not pleased with the earlier version that hasn’t been found. Although Vista-Scope ’70 was included in the August 1970 wardrobe guidelines, it isn’t mentioned in the advance release or the final uniform standards.

There are other notable differences between the advance release and the final standards. In the draft, volunteers with public contact duties were authorized to wear any class of uniform prescribed by the superintendent. However, “the supportive personnel’s zip-up smock was designed to meet the requirements of a volunteer uniform and should be used whenever possible.” The orange pop-on was specified for NPS wives “when serving as official hostesses for Service funcions, either in-house or public.” Wives could also wear the supportive personnel’s zip-up smock or the domestician’s work smock when serving a related function. In the final standards, all volunteer personnel were to wear the pop-on, and a separate NPS wives category was eliminated.

A Departure

The final December 1970 standards acknowledge that “The women’s dress uniform is a departure from the traditional forest green,” once again noting its embrace of the environment and the colors of earth and sand, air and snow, and the sun. In an apparent acknowledgement that the public might not recognize women as NPS employees, it declares, “The dress hat serves as a link to the past and the male counterpart and as initial identification for the park visitor.”

The options in the standards are so variable that charts were needed to clarify which elements could be worn under what circumstances. The dress uniform alone had six options:

-

Class A (Basic): Dress, jacket, tan to light-brown shoes, felt hat, and gold nametag. This uniform was worn for all formal and semiformal occasions, social functions, and official contacts outside the park. On ceremonial occassions the scarf and gloves had to be worn. Discretion was urged in deteriming the use of the hat, which was not recommend for indoor use.

-

Class B (Warm Weather): Basic uniform without the jacket. A straw hat might be authorized instead of the felt hat. The scarf and gloves were to be worn for ceremonial ocassions despite the weather.

-

Class C (Cool Weather): Basic uniform except that the tunic and slacks or tunic and culottes were worn instead of the dress, and boots were worn instead of shoes.

-

Class D (Warm Weather): Same uniform as Class C, but the jacket isn’t worn.

-

Class F: Tunic, jeans, felt or straw hat (depending on season), and shoes or boots (depending on the terrain). The Class F uniform could only be worn in situations where rough terrain or hazardous conditions existed. A parka could be worn in cold weather.

A work uniform was also created for jobs where the dress uniform would be inappropriate. Together with a new uniform for men in 1971, it was the first special uniform created for maintenance personnel. It consisted of:

- domestician’s work smock

- beige or tan to light-brown shoes or boots

- white or dark-brown sweater

- beige uniform coat

- scarf or scarf hat

- gold nametag

- brown leather or straw handbag, depending on the season

If the duties were conducted outdoors in extreme weather conditions, the Class F uniform without the hat could be authorized by the superintent.

Under “special uniforms,” cooperating association personnel could be authorized to wear the support personnel zip-up smock. Improbably it was also suggested that this zip-up smock could serve as a maternity uniform. All volunteers were assigned the orange pop-on. The lifeguard uniform consisted of a one-piece “classic” swimming suit in bright orange, a bright orange nylon shell jacket, and a bright orange baseball cap. The swimming suit was marked with the standard American Red Cross livesaving emblem on the lower left side of the suit. An NPS arrowhead patch was sewn on the right top of the jacket, and the gold nametag was worn above it. The white nurses uniform remain unchanged from earlier versions.

Setting the Record Straight

The women’s 1970 beige uniform is one of the most misunderstood NPS uniforms (see also the Myth of the Men’s Uniform). The context in which the uniform was created has been described above. Three specific myths about the uniform concern miniskirts, boots, and badges.

Contrary to popular beliefs, miniskirts—or indeed any skirts—were not part of the 1970 uniform. In fact, the NPS never authorized a uniform miniskirt. The culottes seen in photographs have been mistaken for skirts by some (which is, after all, the point of culottes!). The prescribed length for the basic dress and culottes was no shorter than one inch above the knee. In fashion terms, this is “above-knee” length. Although this was a loosening of the previous standard that required the hem be at the knee when kneeling, it doesn’t equate to miniskirts, which were worn at mid- to high-thigh. In practice, dress and culotte lengths varied by women—and what their supervisors allowed. Indeed, even the photograph above from the June 1970 fashion show documents that women wore varying hem legths at, above, and below the knee. It’s imporatnt to note, however, that the photographs taken at the public unveiling represented the uniform six months before the official standards were released. Although some women undoubtedly wore higher hems, it wouldn’t have been in keeping with the 1970 uniform standards.

The description of the uniform footwear is worth further discussion because of the confusion created by the cover of Workman’s women’s uniform report, which references go-go boots. White go-go boots were never part of the uniform standards. Specific shoes weren’t bought from the uniform supplier. Rather, women were given guidelines to follow when buying new shoes or evaluating what they already had in their closets. The December 1970 Uniform Standards—and available earlier drafts—specify the uniform footwear as:

- Shoes should be simple in styling and have a comfortable heel. Color should be beige or tan to light brown in the same color family as the basic uniform, smooth or lightly grained leather (not suede or reptile).

- Boots should be simple in styling and comfortable and for winter should have warm lining. Again, color should be beige or tan to light brown in the same color family as the basic uniform in smooth or lightly grained leather (not suede or reptile). Work boots should coordinate as nearly as possible.

In pre-publication correspondence with Workman preserved in the NPS History Collection, Durham states that she “detested everyone calling them go-go boots” (yet he put that on the cover anyway). Although the boots may look pearlescent white as printed, the original photograph and others taken the same day clearly show they were tan. A review of dozens of available photographs of women wearing the 1970 uniform show women wearing low-heeled tan or brown shoes or do not show the footwear. A woman riding a horse wears cowboy boots in one photo.

Like hemlines, it’s possible that a small number of women did wear white vinyl go-go boots with their uniforms, but if they did it was an individual or local change not in the official uniform standards. All the photos cited as evidence of the go-go boots feature Durham and were taken on a single day at the June fashion show at Independence. Workman’s cover photo and tagline, together with the historical association of miniskirts and go-go boots, resulted in sexualization of NPS women and this uniform. Inevitably when the 1970 beige uniform is discussed in the media or elsewhere, the focus is on “miniskirts and go-go boots” rather than what women in the early 1970s were accomplishing as professional NPS employees, how the public treated them differently from men rangers because of the uniform, or the barriers they faced in expanding into different fields within the NPS.

The issue of the NPS badge and the women’s uniform is more of a misunderstanding than a myth. It is true that, unlike the earlier 1962 uniform, women couldn’t wear the NPS badge with this uniform. However, many men could no longer wear it either because in the 1969 uniform standards, Director Hartzog limited wearing of the badge to “personnel involved directly in law enforcement, trained in law enforcement, or as might be designated.” Women weren’t excluded from wearing the badge per se because of this uniform. However, policies limiting women from moving into law enforcement positions were based on their gender. Beginning in February 1974 women could wear the gold “National Park Ranger” badge with the traditional and field uniforms, but not the Class A dress or pantsuit.

Women React

In 1972 Kathleen Higgins, supervisory park guide at Mesa Verde National Park, wrote a letter to the editor of the NPS Newsletter stating, “I have been quite disturbed over the new women’s uniform for a long time, but really did not see what I could do about it. Said uniform is most impractical for Mesa Verde, and it occurs to me that this may be the case in some other areas.” Her complaints about the uniform were many:

- The material the uniforms were made from wasn’t durable, was too heavy for summer months, and snagged easily.

- The uniforms were poorly made, requiring “constant repair of unsewn seams.”

- The manufacturer suggested hand washing the uniform only, which affected how crisp it looked. The heavy fabric weight resulted in more perspiration in the summer and the need for more frequent washing. It also meant that it didn’t dry quickly, and women sometimes had to come to work in damp clothing if it was washed the night before.

- The uniform was too expensive—employees could rarely afford more than one of each required item, making all the other problems worse.

Higgins suggested that a uniform of a white, roll-sleeve blouse with arrowhead patch, tan (wheat-colored) Levi jeans with belled-bottoms, lightweight hiking boots, belt, nametag, and NPS pin would be more practical and more affordable for women.

June T. Nichols, park technician at Chaco Canyon National Monument (now Chaco Culture National Historical Park), fired back in another letter to the newsletter editor. She disagreed with all that Higgins complained about, saying that she had had none of those problems. Her only complaint was related to the uniform’s fit.

Your true size doesn’t mean much in “tailoring” when there is only small, typical, and large mailed out. (I gave my measurements, drew a picture, and said I was “pear shaped.” What did I get? A dress that was too tight in the hips and sagged at the bust)! Let’s give the uniform a chance but suggest a uniform company to handle the product so we do get a tailored uniform.

Other women complained that the uniform was too cold in the winter. Another issue evidenced in the uniforms in the NPS History Collection is that dye batches were poorly matched, resulting in different shades of beige between dresses, tunics, trousers, and jackets. Several women noted that the uniform was flammable and could melt if they got too close to a fire.

Ruthanne Heriot recalled her experience with the new uniform in 1984.

For me, this "ranger hat" typified the problems with these uniforms: it was hard to keep on, got dirty very quickly, and the fabric did not stand up well at all. The uniforms themselves, being double-knit polyester, snagged quite easily and seams tended to split. As a historian, I wasn't that active out-of-doors but those women who were had more problems. As a curator, I wound up wearing a "uniform" of beige jeans and my white shirt with the arrowhead patch for identification.

Heriot’s “uniform” sounds much like what Higgins recommended. Durham described her experience with the uniform this way in 1996:

The idea of change, with options, was good; the final design was NOT AT ALL what any of us who’d made suggestions for change over the years had in mind. The fabric was a nightmare, and the color was totally useless for any park outside the streets of New York or Philadelphia. The polyester caught every snag imaginable, and it was hot and uncomfortable to wear. I can guess that the female rangers at Mesa Verde (whose plight in crawling through tunnels & up rope ladders in tight skirts was what led me to ask for changes) saw only VERY LITTLE improvement in their situations. And that was only because pants were an option, even if the pants were an impossible fabric & an impractical color.

The monetary cost of creating the 1970 women’s uniform is unknown. Despite the investment, the uniform was replaced in February 1974. Women who hoped that new regulations would allow women to wear the standard NPS uniform were disappointed. Although the new uniform included a “traditional uniform” option that more closely resembled the men’s field uniform, the dress and field uniforms were dark-green polyester. Durham perhaps best sums of the position of many women when she wrote on August 29, 1996,

Most of the women I talked with accepted the 1970 change with the idea that at least we’d seen CHANGE, and that the next push was to get us into the standard uniform. We looked at the 1970 uniform as a first step to be tolerated only as long as we had to. I have to tell you that the [1974 uniform change] was a bigger disappointment to me. To lobby for, and hope for, acceptance as an equal in dress as well as job—and then to be handed a change in fabric and change in color to green (as if that made use equal), was truly a letdown. I can’t tell you how elated I was when we finally were able to buy the gray shirt and green pants.

Sources:

--. (1970, April 2). “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Ranger…” NPS Newsletter, Vol. 5, No. 7, pp. 1-2, 7. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

--. (1970, July 29). “National Park Service Guides Outfitted in Style by Designer.” The Herald Statesman (Yonkers, New York), p. 20.

--. (1970, July 29). “She Perks Up Park Personnel.” Daily Mount Vernon Argus (White Plains, New York), p. 16.

--. (1977, February). “Three WASO Brass Retire.” National Park Service Newsletter, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 5. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/newsletter-v12n2.pdf

Higgins, Kathleen. (1972, February 7). “Feedback.” [Letter to the editor]. NPS Newsletter, Vol. 7, No. 2, p. 4. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Delozier, Loretta. (1970, April 2). “Vista-Scope ’70 Design and Concept.” NPS Newsletter, Vol. 5, No. 7, pp. 3-6. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Delozier, Loretta. (1970, July 9). “Behind the Seams.” NPS Newsletter, Vol. 5, No. 14, pp. 3-4, 6. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Durham, Marion, J. (1989, November). “NPS Women and Their Uniforms.” Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, Vol. 34, No. 11, pp. 19-21. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/courier-v34n11.pdf

Heriot, Ruthanne. (1984, March). “A Personal Memoir on NPS Women’s Uniforms.” Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 32-33. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/courier-v29n3.pdf

Nichols, June T. (1972, March 6). “Feedback.” [Letter to the editor]. NPS Newsletter, Vol. 7, No. 4, p. 6. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

NPS Oral History Collection (HFCA 1817). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

NPS Uniform Records (HFCA-01249). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. (1970). Fall and Winter 1970 Catalog. Kansas City, Missouri. Accessed January 16, 2024, at https://christmas.musetechnical.com/ShowCatalog/1970-Sears-Fall-Winter-Catalog

Sears, Roebuck and Company. (1970). Fall and Winter 1970 Catalog. Kansas City, Missouri. Accessed January 16, 2024, at https://archive.org/details/1970-sears-fall-winter-catalog_202308/page/n1/mode/2up

Vanston, Christine. (1970, July 19). “Design for Guiding.” The Times-Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), p. 25.

Workman, R. Bryce. (1998). Breeches, Blouses, and Skirts, 1918-1991. National Park Service Uniforms #4. National Park Service, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Tags

- antietam national battlefield

- chaco culture national historical park

- ford's theatre national historic site

- independence national historical park

- lake mead national recreation area

- mesa verde national park

- sitka national historical park

- walnut canyon national monument

- nps history collection

- nps history

- hfc

- uniform

- uniforms

- women

- women history