Last updated: August 3, 2023

Article

(H)our History Lesson: WWII Conscientious Objectors at Patapsco Camp

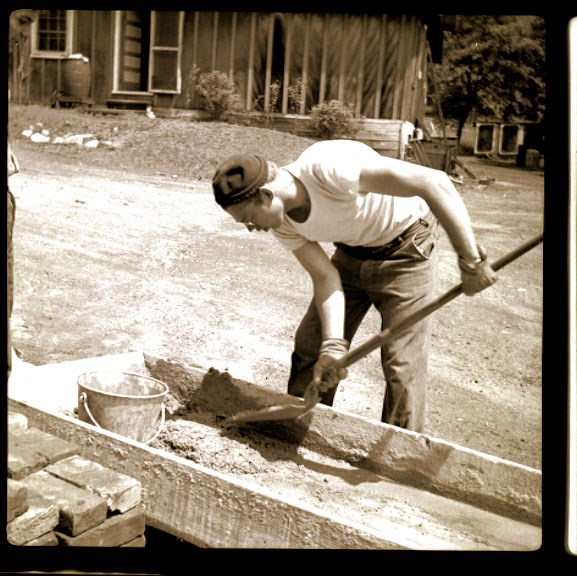

Courtesy Swarthmore College Special Collections, SCPC, DG056_CPS_Camp3_GroupPhoto

Introduction

During World War II, thousands of pacifists objected to military service because of their religious and moral beliefs. Some of them participated in a new iniatitive, the Civilian Public Service program, which allowed them to do "work of national importance" without violating their principles.

This lesson was adapted from the article Patapsco Camp (WWII Civilian Public Service Site). It can be taught as part of a unit on pacifism, the Civilian Public Service, World War II, and/or when teaching World Religions. The lesson has two readings and three activity choices, where a combination of all or some can be used to learn more about the topic. Each activity choice integrates reading and writing skills.

Grade Level Adapted For

Grades 6-12

Lesson Objectives

Students will be able to...

- Examine and evaluate primary and secondary sources to ask and answer historical and perspective-taking questions.

- Explore the ways that culture, specifically religion, shows continuity and change in communities under pressure in World War II.

- Write in opinion, informative, and/or narrative styles to share and connect to historical information.

Essential Question

How did Conscientious Objectors (COs) contribute to the development of the US during World War II?

Courtesy Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

Background Readings

The primary and secondary source readings below will introduce students to the story of conscientious objectors at Patapsco Camp.

Teacher Tip: Direct students to underline or circle surrounding context clues that provide context to the unknown words. Tell them to consider perspectives of those described, along with the varying beliefs the readers of the article may have held.

Reading 1: Primary Source

Reading #1 is a newspaper article from the Gettysburg Times in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania from February 20, 1941. The report describes the opening of the new camp.

From The Gettysburg Times (Gettysburg, PA), Feb. 20, 1941. (Source)

Washington Feb. 20 – One of the strangest phases of national defense will open its doors soon. It is privately financed and only partially provided for by law and recognized by the military as an integral part government supervised, but it is of the defense set-up. It is the first camp of conscientious objectors. With 125 to 150 boys, whose religious or conscientious scruples prevent their taking part in any militaristic activities, Patapsco State Park camp, near Baltimore, Maryland, will be the first of a nationwide network of camps where lads who will not spill blood will do their civilian bit by giving a year of labor to work that is useful to the nation and a contribution to the national welfare.

Patapsco is an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp and what these boys will do there it [sic] not a great deal different from the non-militaristic activities of the CCC. They’ll contribute to reforestation, soil conservation, road construction, and the hundred or so other things which are considered vital to national welfare, but which have nothing to do directly with the defense program.

The C.O.’s who will go into these civilian camps should not be confused with those who will be inducted into the army for non-combatant training, such as that in the medical corps. The latter’s scruples forbid only participation in actual combat.

6,700 Already Listed

Plans for the civilian training camps, of which Patapsco is the first, were prepared by several government agencies, and the National Service Board of Religious Objectors. This latter is a coordinating board which represents all the religious groups whose beliefs forbid participation in wars or war activities.

The plan was given the official stamp recently when President Roosevelt issued an executive order setting the machinery in motion.

About 25 camps are already planned but it is expected that the number may reach 100 or more before next fall. With camp sites and some equipment provided by the CCO, with other equipment provided by the Army, with work direction by Agriculture and Interior department experts, these camps will offer work for the unofficially estimated 6,700 young men who already have been classified by Selective Service as conscientious objectors.

An odd thing about the C.O. work camps is that although Congress set them up in the Selective Service Act, no funds were provided for financing them. Thus the actual maintenance of the camps will be financed by the purely private National Service board. There is a request in Selective Service’s 1942 budget for maintenance of the camps, but Paul C. French, Quaker secretary of the National Service board, says the board does not want any government funds and for the present, at least, would rather do its own financing. With food, clothing, medical care and salaries of supervisory personnel, it is expected that the maintenance cost will run about $35 a man per month.

One Objector

At least one amusing story has come out of the preliminary plans for the C.O. camps. Officials tell of one patriarchal Minnonite [sic] farmer who inquired what his pacifist sons would have to do in the camp. He was informed that they would have to work eight hours a day. The old farmer exploded like a volcano.

“Eight hours,” he shouted. “No son of mine is going to a place like that. Fourteen hours is a good day’s work. These camps will only send my sons home lazy.”

Reading 2: Secondary Source

Reading #2 is a secondary source summary of conscientious objection during World War II, the creation of the Civilian Public Service program, and experiences and controversies at Patapsco Camp.

Excerpt by Sarah Nestor Lane (October 2022)

Background

Voluntary enlistments accounted for less than 40 percent of service members in World War II; the rest were drafted. Those who objected to the draft were called conscientious objectors. For those who objected to the draft for religious reasons, they did so because they belonged to churches that viewed any violence as incompatible with Christianity, and against their longstanding faith commitments. Conscientious objectors (COs) had three options: join the armed forces in a non-combatant role (ex. medic), volunteer with the Civilian Public Service (CPS), or go to jail. CPS was provided under the 1940 Selective Service and Training Act. This law sparked controversy as it provided for the first peacetime draft in US history. In May 1941, CPS camps began to open, with Patapsco Camp in Elkridge, MD being the first. The camps were mostly located at prior Civilian Conservation Corps campsites.

Challenges

Many COs faced harassment from civilians who were upset by COs’ unwillingness to fight and risk their lives in combat. However, COs faced other challenges and dangerous situations, such as smoke jumping, where they would parachute into remote areas to fight fires. Some COs participated in human medical experiments such as testing medications and a scientific study measuring the effects of starvation on the human body.

COs were not paid, and their families did not receive benefits, like those in the armed forces did. This caused financial burden on families and pushed some COs to enlist as noncombatants to support themselves and their families. Women weren’t draft-eligible, but a few worked at CPS camps as nurses or dieticians. Some sites allowed wives of the COs to live there, and others did not.

Patapsco Camp Controversies

In total, 154 workers spent time at Patapsco Camp during its existence as a CPS facility. COs at Patapsco worked heavily in building trails and maintaining the woodland area. Their work in protecting and developing natural resources helped to expand and develop the National Park Service. They protested tasks at the camp seen as connected to the war efforts, like building an air raid tower.

Racial tensions, common in a segregated United States, also reached Patapsco residents. In 1942 the Patapsco camp was set to move to Powellville, Maryland, but locals protested the presence of an African American CO. His fellow Patapsco COs refused to transfer in solidarity, but in the end, the African American CO was transferred to a different camp. The move did happen, which lead to the closure of the Patapsco camp in 1942.

Reading Responses

Teaching Tips: Before answering the questions, have students meet within small groups to discuss any unknown terms, or questions about the ideas in the background readings. You could assign a question or two to different small groups to report back on to the whole group, as a “jigsaw” strategy, to shorten this part of the lesson.

- What were conscientious objectors’ options if they would not participate in the armed services?

- What needs did Patapsco camp, and other C.O. camps like it, fill? (Consider the needs of COs, the community, and natural resources.)

- What were the COs contributions to environmental and park spaces?

- How were COs and their family’s needs met, or not met? Describe the additional impact of one’s race and gender.

- Compare the primary and secondary source readings. What information varies between the two, and why do you think that is? Compare author’s purpose and place in time.

- Reread the last section, “One Objector,” of the newspaper article from The Gettysburg Times. Describe the author’s tone and voice. Why may the author have included this short vignette (story)?

Courtesy Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

Activities

Teaching Tip: You could provide each of these three activities on a menu as a choice to students to choose from, or provide the one that aligns to your current English Language Arts objectives.

1. Letter to the Editor

Subject integration: Opinion writing, letter writing

The opening of Patapsco Camp and other CPS camps attracted intense scrutiny from the public and media. One paper called it “one of the strangest phases of national defense.” Imagine you have read this description in the paper, develop an opinion about the camps, and decide to act upon it.

Write a letter to the editor to respond. A letter to the editor is a way to respond to an article published in a newspaper that includes your own opinion, and usually includes details to prove your point. Letters to the editor are published so the public can read your opinion in connection to a previous article. Include the following in your letter.

- Do you agree or disagree with the description, “one of the strangest phases of national defense,” and why?

- Clearly share your opinion on the impact of the COs at CPS camps, and use historical facts, from the primary & secondary sources, to help prove your point.

- Make sure your writing is using appropriate past and present tenses (you are pretending to write at the time of the CPS camps opening).

Further reflect with peers after writing: Do you think your opinion aligns with those held by Americans at the time? Why or why not?

Activity extension: Global Perspectives

Conscientious objector issues were not isolated to the United States. The following is an example excerpt from a letter to the editor in London, England, regarding the pay of conscientious objectors for their work during the war in non-combatant and civilian roles:

“ . . . But the question also arises: ‘Why should anyone, whether a conscientious objector or over military age or engaged in a reserved occupation, be allowed to earn higher wages than the soldier in the field? To place everyone on the soldier’s footing would meet with formidable obstacles, but it would help to ensure that the war was not unnecessarily prolonged through the working of vested interests. – Yours, &c., Donald H. Whitmore”

- How do you think views on conscientious objectors did, or did not, vary across different country’s home fronts?

- How is religion an example of culture showing both continuity and change?

[Source: “Letters to the Editor: The Further Question,” The Manchester Guardian (London, England), April 2, 1940, 12.]

2. Historical Marker Design

Subject integration: informational writing, media, and design

Develop a new, informative, media-integrated historical marker that could be displayed at the Patapsco Camp site to tell the story of the COs. Use the information from the primary and secondary sources. The marker could be designed using a digital design platform, a slide, or poster.

The marker should include:

- A timeline of important dates, such as the start of the war, the date of the camp opening, and the date of its closing.

- The “why” of CPS camps and the work done by the COs

- Images with captions

- A way for readers to get more information (ex. a QR code, or recommended website)

- Other details that would interest visitors to the site.

Use this site for reference on historical markers in use today.

3. Patapsco Camp Perspective-Taking

Subject integration: Narrative writing

Directions: Pretend you were a conscientious objector in World War II who joined the Civilian Public Service and was at Patapsco Camp. Take on what you believe to be, based on the sources, their historical perspective. Write a series of first-person journal entries that outline the following (blend creativity with the historical facts you have learned to develop the story):

- The beliefs that lead you to be a conscientious objector

- Why you decided upon the CPS route, rather than other options

- The activities and work you did at Patapsco Camp, along with challenges you faced

This lesson was written by Sarah Nestor Lane, an educator and consultant serving the National Park Service’s Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. This lesson was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.