Part of a series of articles titled Conversations about Legacies of Slavery .

Article

(H)our History Lesson: The Shields-Ethridge Farm, Two families, Two fates

This lesson was adapted by Talia Brenner and Katie McCarthy. If you're interested in more information and activities on this topic, explore the Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan “The Shields-Ethridge Farm: The End of a Way of Life.”

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for middle school learners, but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives:

Learners will be able to...

-

Understand how systems of slavery affect generations of people by creating unjust economic and social systems.

-

Read about the experiences of two families and how their lives differed based on the institution of slavery.

-

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

-

Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source.

Inquiry Question:

How did the institution of slavery affect generations of Americans?

Background:

From the late 1700s until the early 1900s, two different families lived at the Shields-Ethridge Farm. One family, the Shields-Ethridge family, were white landowners. The other family was descended from Leah, the first enslaved woman at the farm. Members of this family were African-American enslaved laborers and later wage workers and sharecroppers on the farm. Over 150 years, the members of these families experienced very different fates. In this lesson, students will trace these two families’ experiences at the Shields-Ethridge Farm, learn how these experiences relate to other events in U.S. history, and consider ways of making amends.

Reading

In 1799, Leah, an enslaved woman, and her infant daughter Sophia were sold to the Shields Farm.1 Both mother and daughter were bound to a life of slavery. Joseph and Peggy Shields purchased Leah and Sophia. The Shields had moved to northeastern Georgia only a year before.2 Joseph had inherited the money to start his plantation from his father.3

The couple were likely drawn to the area by the promise of large tracts of inexpensive land. White settlers had forced Native Americans off the land.4 The Shields-Ethridge Farm is located on land that been home to Cherokee tribes until 1784.5

During the early 1800s, Leah, Sophia, and other enslaved laborers farmed tobacco at the Shields Farm.6 Enslaved people received none of the profit they created. Instead, the Shields family grew richer and expanded their business. By 1810, the Shields enslaved four people. By 1820 the Shields enslaved seven people.7

In addition to the tobacco crop, Joseph Shields made money from enslaved people by renting their labor to other landowners. For example, Joseph and his son James made $96.31 in 1813 (the equivalent of well over $1000 in 2020) from renting out the people they enslaved.8

By this time, three generations of Leah’s family had been enslaved on the Shields Farm. Sophia, sold to the Shields family as an infant, now had children of her own. Her children were possibly fathered by men of the Shields family, because they are listed in the census as “mulatto.” Like many plantation owners, Joseph split up enslaved families as he moved his wealth around. Sophia was separated from her son Spencer, who was gifted to a member of the Shields extended family.9

When Joseph Shields died, James inherited most of his father’s wealth and land. He shifted the farm’s production to cotton, which was quickly becoming the new cash crop in northeastern Georgia.10 James Shields continued to expand the land he owned. To do so, he used both his own investment skill and government assistance. For example, the state of Georgia gave out land lots to Revolutionary War veterans and widows. James’ mother and mother-in-law both received land through this program. James later inherited these properties.11

By 1860, twenty people were enslaved on the Shields Farm. James, his wife Charity, and their family continued to profit from the cotton crop that enslaved people produced. In addition to supplying labor, enslaved people could be sold for large amounts of money. In the United States, the children of enslaved people were born enslaved. James increased his wealth over time by selling enslaved children and splitting up families. When James died in 1863, his estate was valued at $17,000 in Confederate currency. $13,300 of that amount was based on the people he enslaved.12

After the Civil War, formerly enslaved people on the Shields Farm now had their freedom, but had no money or property. They also faced a violently racist society where imprisonment and lynchings were common. In 1865, the year the Civil War ended. Sophia and her daughters Jarvy and Dicy signed a labor contract with Charity Shields, who had inherited her husband’s property. In this contract, they agreed to do the same work they had done when they were enslaved. Now however, they received a small wage for their labor. Other members of Sophia’s family continued to work in the Shields cotton fields.13 Across the South, many Black people continued to work on the plantations where they had been enslaved, lacking the means to go anywhere else.

Against the odds, some of Leah’s descendants eventually managed to purchase land. By 1875, Jarvy, who took the last name Shields, owned her own land.14 But the Shields family still had more land than Leah’s granddaughter ever would. Many of Jarvy's relatives never managed to became landowners.

In 1910, Ira Ethridge inherited the Shields family's property. Some formerly enslaved people were still working on the farm, now called Shields-Ethridge. Instead of working as wage earners, as they had after the Civil War, laborers now participated in a system called sharecropping. As sharecroppers, they rented from the landowner, in this case, Ira Ethridge. Most sharecroppers at the farm could afford to rent fewer than 10 acres, a small percentage of the Shields-Ethridge property.15

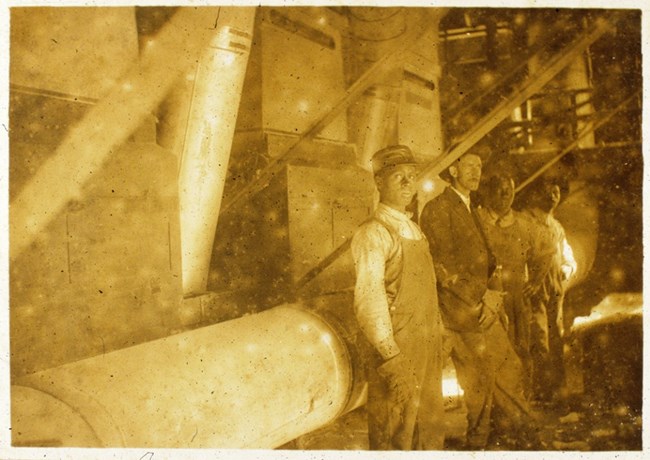

All year, sharecroppers performed the physically grueling work of farming cotton on the land. Each winter, sharecroppers repaired equipment and prepared the fields for planting. This work involved pulling out old stalks and plowing the field with the help of mules. In April, sharecroppers planted cotton seed. Throughout the spring, they thinned and weeded the growing plants. In the early summer, the cotton needed “chopping,” which consisted of removing weeds from around the cotton stalk. “Mopping” the plants with a mixture of arsenic and molasses was needed to kill boll weevils, a beetle that threatened the cotton crop. In the fall, families of sharecroppers picked the cotton bolls, which required bending and pulling for very long hours. The cotton then had to be cleaned, or “ginned.” The work was nonstop. Children on the Shields-Ethridge Farm were told to remove enough seed from the cotton bolls to fill their shoes before being allowed to go to bed. Each January, when the sharecroppers’ cotton was sold, Ira Ethridge kept 50% of the profit. From the sharecroppers’ 50%, he subtracted the money that sharecroppers had spent at the store Ira Ethridge ran. This system kept most sharecroppers in a cycle of debt. Sharecroppers had to continue farming cotton on rented land in order to pay the landowner back for the previous year’s debt. For extra money, sharecroppers also worked for wages in Ethridge’s own fields and in other side ventures like running a barbershop.16

There were both African-American and white sharecroppers on the Shields-Ethridge Farm. As late as the mid-twentieth century, some of the Black sharecroppers were descendants of people who had been enslaved on the Shields-Ethridge Farm.17 White sharecroppers were also very poor, but they had opportunities that Black sharecroppers did not. For example, between 1909 and 1938, the Bachelors’ Academy on the Shields-Ethridge Farm served as a public school for white students.18 The children of both white landowners and white sharecroppers could attend. Black sharecroppers’ children, however, had to walk to a segregated school that was farther away. That made getting an education, and all the benefits that come with it, much harder for Black children.

In the 1940s, cotton production and the sharecropping system began to die out on the Shields-Ethridge Farm. This was largely because of new agricultural technology. In this time period, huge numbers of African-Americans moved from the rural South to cities in the North in what is called the “Great Migration.” Yet the effects of 150 years of life on the Shields-Ethridge Farm did not go away. Two different families lived on the Shields-Ethridge Farm: the Shields-Ethridges and the descendants of Leah, the first enslaved woman on the plantation. Though all generations made their own decisions, they inherited different constraints and opportunities.

Discussion Questions:

-

How did Joseph and Peggy Shields get the land that became the Shields-Ethridge farm? Who was this land available to?

-

What were three ways the Shields family made money from enslaved people?

-

Why do you think Sophia, Jarvy, and Dicy signed the labor contract with Charity Shields after the Civil War?

-

What are some of the benefits of getting an education? What do you think were some of the effects of it being harder for Black children to get an education?

Footnotes:

1 Frances Patricia Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece: Two Centuries of Agricultural Change at the Shields-Ethridge Farm,” M.A. thesis, (University of Georgia, 2002), 23.

2 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 9.

3 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 7-8.

4 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 11.

5 Shields-Ethridge Farm National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (May 22, 1992),

http://www.shieldsethridgefarminc.com/pdfs/NR-Shields-EtheridgeFarm.pdf, 16; Elizabeth B. Cooksey, “Jackson County,” New Georgia Encyclopedia (July 14, 2006; last edited July 25, 2018),

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/jackson-county#:~:text=Jackson%20County%2C%20in%20northeast%20Georgia,War%20(1775%2D83).; “County History,” Franklin County, https://www.franklincountyga.gov/county-history/.

6 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 16.

7 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 17.

8 Receipt, Early Records, Shields-Ethridge Papers, in Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 17.

9 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 24.

10 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 16.

11 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 18, 20.

12 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 27.

13 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 32.

14 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 33.

15 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 52.

16 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 54.

17 Stallings, “Presenting Mr. Ira’s Masterpiece,” 33.

18 Shields-Ethridge Farm National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (May 22, 1992),

http://www.shieldsethridgefarminc.com/pdfs/NR-Shields-EtheridgeFarm.pdf, 19

Activity:

Understanding Experiences

Divide learners into five groups. Assign each group one of the following topics:

-

Land ownership

-

Inherited money and land

-

Access to education

-

Income

-

Physical and mental health

Have each group review the reading and discuss the ways that the two families had different experiences in terms of this topic over time. For some of the topics, such as “physical and mental health,” and “access to education,” students may speculate about information not provided in the reading. Have each group present their findings to the class.

Then, lead a discussion about the ways in which the two families fared differently over the generations. Who or what is responsible for that gap? Finally, ask learners how it might be possible to make amends.

Wrap-up:

-

Why might this topic matter to you or the people around you? Why might it matter to the country or to the world?

-

What is something you found really important in your research? Why do you think it happens that way?

-

What does this topic make you want to explore?

Additional Resources:

Shields-Ethridge Heritage Farm

The official website of the Shields-Ethridge Farm provides in-depth content about the family members, historic buildings, agriculture, and history of the farm. The site also has information about visiting the farm in small or large groups, with the farm's mobile app, or for public events.

Last updated: May 11, 2023