Part of a series of articles titled Dayton and Montgomery County, OH, WWII Heritage City.

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Navy WAVES Building Decryption Bombes in Dayton, Ohio

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. No known restrictions.

About This Lesson

This lesson is part of a series teaching about the World War II home front, focused on Dayton and Montgomery County, Ohio as an American World War II Heritage City. The lesson contains photographs, background reading, and two primary sources to contribute to learners’ understandings of the Navy WAVES contributions to building Bombes, a decryption machine for military intelligence, in Dayton, Ohio. It was written by educator Sarah Nestor Lane.

Objectives:

- Identify reasons why Dayton was selected as the location of building the Bombes.

- Describe the accomplishments of the Navy WAVES in Dayton, OH.

- Explain: a) reasons why women chose to enlist in the WAVES and b) the impact the WAVES had on military intelligence decryption efforts.

Materials for Students:

- Photos 1 - 6 (can be displayed digitally)

- Readings 1, 2, 3 (two primary, one secondary)

- Recommended: map of the Dayton area, Montgomery County, or the state of Ohio, to plot locations.

- Extensions: 1) Videos 2) Additional primary source reading

Getting Started: Essential Question

How did the Navy WAVES located in Dayton, Ohio contribute to the home front intelligence efforts?

Read to Connect

Teacher Tip: This is a primary source document to set the scene in understanding why the WAVES were sent to Dayton, Ohio, after their initial training. It may help students to revisit this document for new understandings after readings 2 and 3.

THE NATIONAL CASH REGISTER COMPANY

Dayton, Ohio

Office of The President

April 7, 1943

Capt. E. S. Stone

Ass’t Director, Naval Communications

Communications Annex

Nebraska Ave. & Massachusetts Ave., N. W.

Washington, D. C.

Subject: Use of Navy WAVES, and quartering thereof, in the execution of Navy Contract NSX 7892

Dear Sir:

(1) It seems desirable in the execution of subject contract to employ WAVES in certain assembly and soldering operations.

(2) The National Cash Register Company wishes to offer to the Navy Department the use of its summer camp, known as “Sugar Camp,” for quartering the necessary enlisted WAVES, mentioned in Paragraph (1).

(3) Sugar Camp includes 240 beds (4 to a cottage), which should be ample to quarter some 300 necessary enlisted WAVES, operating on shifts, as proposed.

(4) It is necessary to have 75 at the camp on or about April 19th and 225 on or about May 3rd.

(5) The National Cash Register Company proposes to furnish quarters, meals, and recreational facilities at the camp at a post not to exceed $2.75 per day, per person.

(6) Policing of the enclosed area will be accomplished by The National Cash Register Company civilian guards. In addition, a civilian caretaker and his wife have permanent residence at this camp.

(7) Since Sugar Camp is located on property owned by The National Cash Register Company, within easy walking distance of the Factory, no transportation costs will be incurred by the enlisted personnel.

(8) It is the intention of The National Cash Register Company to provide comfortable and homelike facilities for the assigned complement of WAVES. The camp has a swimming pool and other recreational facilities all of which will be available for their exclusive use.

Very truly yours

/s/ S. K. Allyn

Enclosure (A) VCNO Conf Serial 0833420

By Sarah Nestor Lane

Teacher Tip: This is a secondary document to provide more background information to connect to Readings 1 and 3.

President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Navy Women’s Reserve Act into law on July 30, 1942. This created the WAVES, which stands for Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. The WAVES helped meet the onshore needs of the US Navy while men were out at sea. The US Navy assigned most WAVES to aviation units. For example, the roles of some WAVES roles were to fix airplanes or to train men on celestial navigators. WAVES were first trained at Hunter College in New York City before going to a station.

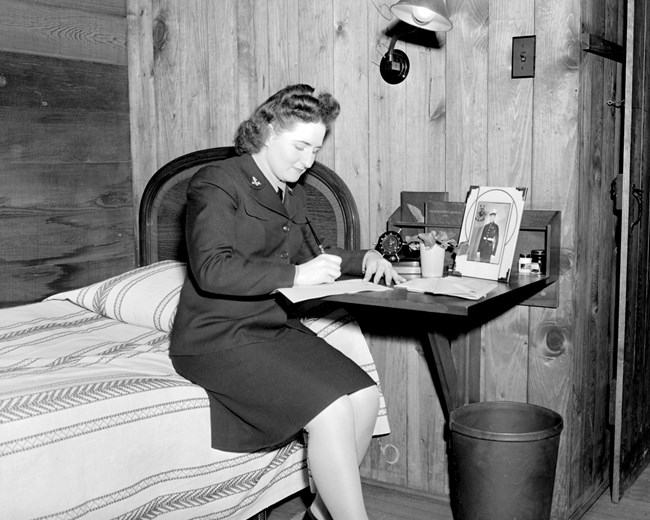

WAVES at Sugar Creek Cabins, Dayton

John Patterson built the Sugar Creek Cabins. Patterson was the original owner of National Cash Register (NCR). Built in the 1920s, the cabins housed NCR salesmen while they were being trained. WAVES went to Dayton, Ohio and resided in these cabins. The area supported recreation with a dining hall, outdoor pool, and baseball diamond. In their free time, WAVES used these and played baseball games. They also visited other local spots like the night club, theater, and restaurants. Twenty-four WAVES got married while in Dayton. Some marriages were to service members from the local military stations and airfields.

The WAVES worked in three shifts around the clock. An 8 a.m. - 4 p.m. shift day started with morning routines, breakfast in the NCR cafeteria, and then marching. WAVES marched to their building with the rest of that shift's WAVES. They worked their shift, returned to camp, ate dinner, and then relaxed.

Codebreaking: Bombes

So, what work did the WAVES do during their shifts? The WAVES in Dayton used the NCR factory to assemble Bombes, a decryption machine for military intelligence. A man named Joseph Desch, who worked at NCR, helped to design the Bombes. The government recruited Desch because he developed the first electronic calculator at NCR. The Bombes Desch designed were top-secret machines. The Bombes simulated a reversal of the four-rotor movements of the Enigma coding machine found on German submarines. The British had designed a Bombe that was successful at the start of the war. The British Bombe became ineffective after the Germans added a fourth rotor to the coding machine. The Bombes designed by Desch was six times faster in decrypting and worked with the four-rotor German machine.

The WAVES assembled the machines in Dayton’s NCR Building #26. Each machine weighed two tons and was seven feet tall, ten feet long, and two feet wide. The work required speed and accuracy with thousands of small tubes and pieces (see Reading 3). The WAVES built one hundred and twenty Bombes in Dayton. The entire process, from initial prototypes to final products, lasted from 1942 – 1946. The Bombes went to the Naval Communications Annex in Washington, D.C. WAVES went to the same location to help with operations and maintenance of the machines. About 3,000 workers operated the machines at the U.S. Navy facility in Washington, D.C (not all came from Dayton).

Today, there is only one original NCR Bombe remaining. The single Bombe is at the National Cryptologic Museum in Annapolis Junction, Maryland.

Courtesy of the Dayton History Archives.

By the numbers: WAVES (nationwide)

-

Recruitments were aged 18 to 36 (and officers 20 to 50)

-

In total, 90,000 women served in the WAVES (both enlisted and officer ranks).

-

70 enlisted and two officers were African American women (later recruitment).

Quotation to consider:

“That was the very last thing before you left the Navy. You walked in this room and he put the Bible in, and you put your hand on it and I had to repeat after him that I swore I would never tell of my activities during World War II. Like you know the consequences. If you talk, you’ll get shot. We went home and we never talked. Don’t you think that’s remarkable? That 600 women went home, got on with their lives, and never said a word.”

-Veronica Hulick, a member of the WAVES who were stationed in Dayton working with Bombes (from 2001 interview reunion; credit: NCR archives, Dayton History)

Courtesy of the Dayton History Archives.

Questions for Readings 1 and 2, Photos 1-3

-

What living quarters and accommodations were provided to the incoming WAVES?

-

Why was Dayton selected as a city to build Bombes in?

-

Describe the importance of the Bombes.

-

What did the Navy WAVES accomplish while in Dayton? How did this connect to the work in Washington DC?

Interview conducted by Claudia Watson during the Oct. 20, 2001 WAVES Reunion. (Credit: Montgomery Co. Historical Society)

Claudia Watson (CW): So how did you hear about the WAVES?

Sue Unger Eskey (SE): Well, I actually had, I think I had made up my mind to do something like that before I even knew there were going to be WAVES because when I was in high school, I was in a social studies class and we were studying about the war on both sides of the world and we were in the middle. And our teacher went around the room and asked us what we would do if someone attacked our country. Well, with all the bravado of a 17-year-old, I said, Oh, they wouldn’t dare. We’re the biggest, the best, the brightest and so forth and every superlative I could think of to describe our country. And he just sort of thought about it and said, Well, let’s say they do attack, what are you going to do? And, you know, in those days there really wasn’t much for girls to do. There weren’t many career choices for anyone and women didn’t have a large place on the professional scene. So I wasn’t sure at all what I was going to do. . . . And finally I said, Well, I really don’t know what I’m going to do because I’m only a girl, but I promise you I will do something. And it was like I was making a vow, you know, to myself and to him. But it sort of stuck, you know, and then, of course, when Pearl Harbor came the following year and then the WAVES were started about seven months after Pearl Harbor, I investigated the WACS and the WAVES and I decided I wanted to become a WAVE because their standards were higher and I liked the uniforms. I thought we looked more like ladies than the WACS did. There were so many things that I considered in these comparisons. So I made up my mind I was going to be a WAVE.

CW: . . . how did you go about enlisting? How old were you when you enlisted?

SE: By this time I was 20 years old and I wrote to Chicago because Rockford had a recruiting station, of course, but they didn’t have the information about women going into the service as yet. So Chicago was our main recruiting station. So I received brochures and an application and I read through; and the more I read, the more excited I got about becoming a WAVE. So I filled out all my papers and went home the following weekend and expected my parents to sign them. But my mother just absolutely refused and she said, No daughter of mine is going to go into the service. She was just adamant about it. She just didn’t think women had a place in the military. And my father was usually my mentor when I was growing up, so he read them over and he asked me a few questions and finally he said, Well, mother, I’m going to go ahead and sign her papers because she’s determined and you know she’s going to go when she’s 21. So he signed. Well, my mother was furious. She said, David, you don’t know what you’re doing. You’re sending your youngest daughter off to fight in a war. . . . .

SE: So she was really disturbed by it and anyway I sent my papers in and I was given orders to report to Chicago in January of 1943 and I passed all the tests and was sworn into the WAVES. But the first class had already started at Hunter College in New York City where I would be assigned, so I waited for the second class which was beginning on March 3, 1943. So mother and dad took me to the train on March 2 to go to New York City. My mother was very tearful and I’ve never forgotten her parting words of advice. She said, Now, darling, if they don’t treat you nicely, you just come right straight home. [SE laughs.] That was my mother. So I’m on my way to New York City to Hunter College.

[…. After training at Hunter College...]

SE: .. some of us were expecting to go to California because they wouldn’t tell us where we were going, but they sort of let it slip that we were going west, you know, when we were leaving Washington. And, of course, west to us in our younger days meant going to California. So we expected to go on to California .. the great Mecca. And so we had no idea until we got off the train and then the sign on the station said, Welcome to Dayton, Ohio. I thought, Dayton, Ohio? You know, so my mind was open. . . .

CW: Did you have to constantly pay attention [to the Bombes] or was there any like downtime when you were waiting for it to run or was it a constant vigilance?

SE: No. Once we had our machines, um, set .. set up .. we had a menu to set them up .. a printed menu and this told us which wheels to .. how our wheels were to be set. We had 36 wheels on each side of the machine that had to be set. And this told us all of our work instructions and so forth, but we had to check them. And then we checked them again. And then someone else came out and checked them, so they actually were checked three or four times before the machines were turned on. And at first it was not a real slow process. But it took time for us until we got accustomed, you know, to the point where we could just go right down the line with them, so eventually we picked up speed later on. Both speed and accuracy. But we had to be accurate because accuracy was always the name of the game. And speed was very important. So, uh, those things were not too time consuming.

Once the machine was turned on, it would sometimes run for very short runs. And I understand after reading Jennifer Wilcox’ books that those were the three wheel Enigma runs that did the short runs and then those that had the .. doing four wheel Enigma runs were the long runs. And I was so glad to discover that because I was on the left-hand side of the room and I would sit and wait and I’d say, Come on, machine, let’s have a little action here, you know because I wouldn’t be getting very many hits and I’d have to wait a long time. And I would look across the room and the girls on the other side of the room were already setting their machines up for another run and I would think, Come on, here, let’s get with it. Let’s go. [SE laughs.] And then after I read her book I realized, well I had to have been on a four wheel Enigma machine and then I know that the officer of the day that I worked under once in a while would sometimes bring special runs out to me and so I knew that whatever I was doing must have been different from what someone else was doing and, uh, at first it was very tedious for us because we had to stay with our machine. We couldn’t turn our back on our machine. It was rather dangerous because they revolved .. those code wheels revolved about I think it was 7,000 times a minute extremely fast, so it could have been extremely dangerous if you weren’t, weren’t careful. And that’s why I say, I always got 4.0 in safety. I checked all my safety rules, you know. On my test I always got a 4.0 in safety.

CW: What was the danger about turning your back on them?

SE: Because there was no cover on the front of the machine and all these wheels were exposed. Of course, they were about this big around maybe 5, 6 inches in diameter but every one of them was spinning at this very high rate of speed. And if you turned your back on them and accidentally backed up to your machine, you know, there would have been a tragic accident. And then each machine .. each of those wheels was locked in by a toggle switch, and we had to be very sure, you know, that it was absolutely clamped down because I always had visions of one of those wheels flying out and decapitating somebody across the room. So we were very careful with it very, very careful. And, um, the heat sometimes I .. we talked about that .. that the heat made you feel sort of logy sometimes, also. So when you were working toward the front of the machine when the machine was on, it would just get awfully hot. And then we had banks of cabinets behind us that had extra wheels in these cabinets. So we were sort of closed in between the machine and the cabinet, you know, so the air didn’t circulate too well at first. And eventually they did put some sort of an air conditioning system in which helped an awfully lot. But it got to the point where they allowed us to write letters. We could bring magazines in as long as they were checked at the guard house when we came through. And if we brought anything else in that couldn’t go in to the room, if we came in with packages or something like that, they were always checked. But we never could take those things in with us. They were always kept at the guardhouse.

Courtesy of Dayton Codebreakers, Montgomery Co. Historical Society

Questions for Reading 3, Photos 4-5

1. Why did Sue Eskey enlist in the WAVES?

2. Describe Eskey’s work with the Bombes. Include her tasks and the dangers of the work for the WAVES.

3. How do you think Eskey's enlistment story and time in Dayton compares to other WAVES’ experiences?

Extension Activities:

1. Videos

Support your students’ understandings with more visual, multimedia resources.

-

Watch the documentary clip, “The Secret Dayton Project that Broke the Enigma Code” (8:49) by University of Dayton.

-

See an original, and the last remaining, Bombe that was built in Dayton: WAVES and the Bombe - YouTube (5:07) by the National Security Agency

2. Additional Primary Source reading

Teacher Tip: Note how the WAVES' work is described in the article.

"Fifty WAVES Begin Training At NCR Plant," The Dayton Herald (Dayton, Ohio), Wed, Apr 21, 1943 (p. 5)

“A detachment of about 50 WAVE’s (Women’s Auxiliary Volunteer Emergency Service) arrived yesterday to begin training at the National Cash Register company (NCR).

First of a group of several hundred who will arrive within the next few days, the WAVE’s will learn the operation of bookkeeping machines manufactured by the company, and used by the U.S. navy department.

The WAVE’s will be quartered at Sugar Camp on Schantz Avenue, summer camp maintained by the NCR where the company conducted schools for its salesman in previous years.”

Resources

Dalton, C. (2013). Home Sweet Home Front: Dayton During World War II.

National Air and Space Museum: Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service: The WAVES Program in World War II

Recruitment Posters | Homefront Heroines: The WAVES of World War II

Tags

- teaching with historic places

- military history

- twhplp

- twhp

- hour history lessons

- wwii

- world war ii

- wwii history

- world war ii history

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- women's history

- waves

- american world war ii heritage city program

- awwiihc

- dayton

- ohio

- world war 2

- women and technology

- women in world war ii

- mid 20th century

Last updated: August 11, 2023