Last updated: December 16, 2024

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Fort Ontario, NY and Jewish Refugees in WWII America

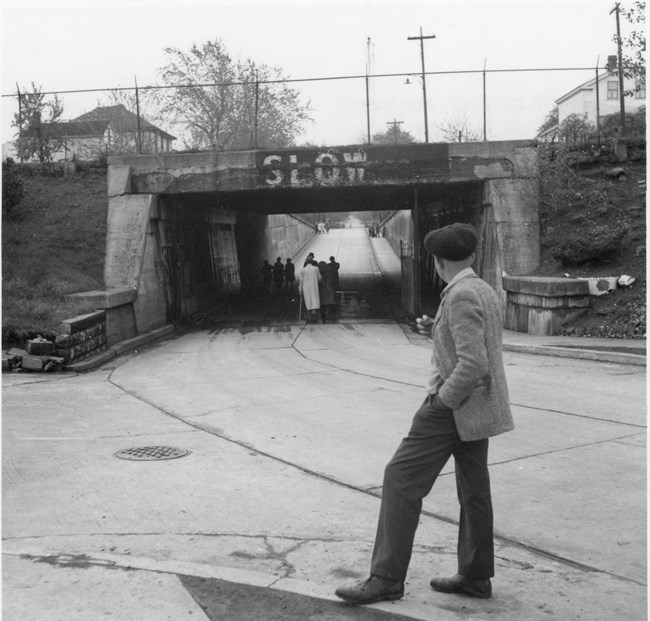

Photo by Hikaru Iwasaki, photographer, US Dept. of the Interior. Public domain, courtesy National Archives and Records Administration.

Introduction

In 1944, 982 Jewish refugees arrived from parts of Southern and Eastern Europe to Fort Ontario in Oswego, NY. These were the only refugees the United States took in during World War II. They lived in the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter for a year before President Harry Truman granted them resident status at the end of the war. Exploring their story helps students understand religion, foreign policy, refugee policy and the World War II home front. It is designed to fit into a larger unit on World War II or the Holocaust.

This lesson is based on a National Park Service article about Fort Ontario.

Grade Level Adapted For

This lesson is for high school learners but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives

Learners will be able to...

- Describe US policy towards Jewish refugees during World War II.

- Compare immigration and refugee policy in the United States during the 20th century.

- Close read a policy document and analyze context that impacts word choice.

- Compare multiple perspectives of an event to form a more complex historical understanding.

Essential Questions

What is the United States government’s responsibility to international refugees?

How should the United States and other countries respond to humanitarian crises?

Vocabulary

Refugee: A person forced to flee their country because of persecution, war or violence on the basis of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular group.

Immigrant: Someone who makes a conscious decision to leave their home and move to a foreign country, to permanently settle there, often through an institutionally sanctioned process.*

*Definitions modified from the UN Refugee Agency and the International Rescue Committee.

Background Reading

When World War II broke out, Nazi Germany had already begun the process of deporting Jewish people from their homes to enforced ghettos and passing antisemitic laws. In 1941, Nazi policy became more extreme, implementing a planned mass murder of Europe’s Jews known as the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.” While some Jewish people were able to emigrate outside of Germany and German-controlled areas, others were trapped as more and more countries in central and southern Europe came to be controlled by or allied with Nazi Germany. The US government did not begin efforts to help Jews fleeing Nazi genocide until 1944. This delay occurred for several possible reasons, including lack of belief of reports on the scale of the violence, complex immigration policy, and antisemitism in the United States. With increasingly horrifying stories coming from Europe, President Franklin D. Roosevelt formed the War Refugee Board (WRB) in order to organize resources and provide support to getting Jewish refugees out of Nazi-occupied countries.

Activities

Activity 1: Primary Source Analysis

On January 22, 1944, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9417, establishing a War Refugee Board.

Have students read the following excerpt from Executive Order 9417 and answer the following questions, individually or as a group.

WHEREAS it is the policy of this Government to take all measures within its power to rescue the victims of enemy oppression who are in imminent danger of death and otherwise to afford such victims all possible relief and assistance consistent with the successful prosecution of the war;

NOW, THEREFORE, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the statutes of the United States, as President of the United States and as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, and in order to effectuate with all possible speed the rescue and relief of such victims of enemy oppression, it is hereby ordered as follows: ...

2. The Board shall be charged with the responsibility for seeing that the policy of the Government, as stated in the Preamble, is carried out. The functions of the Board shall include without limitation the development of plans and programs and the inauguration of effective measures for (a) the rescue, transportation, maintenance, and relief of the victims of enemy oppression, and (b) the establishment of havens of temporary refuge for such victims. To this end the Board, through appropriate channels, shall take the necessary steps to enlist the cooperation of foreign Governments and obtain their participation in the execution of such plans and programs.

– Franklin D. Roosevelt, Executive Order 9417—Establishing a War Refugee Board, Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project

Student Questions

-

What is the purpose of this document? How can you tell from the content of the document?

-

Who does President Roosevelt mean when he says “victims of enemy oppression”? Why might President Roosevelt not specify who “victims of enemy oppression” were?

-

What actions does the executive order say the War Refugee Board will take on behalf of victims? What do you envision that looking like for Jews and other victims of the Nazis?

-

The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 had specific quotas for the number of people who could immigrate to the United States from Central and Southern Europe, where most Jewish refugees were from. What is the difference between an immigrant and a refugee? How is that difference reflected in Executive Order 9417?

Photo by Gretchen Van Tassel, photographer, US Dept. of the Interior. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration.

Background Reading

In the summer of 1944, President Roosevelt issued another executive order. In addition to supporting local efforts in Europe and providing food and other supplies, the War Refugee Board (WRB) would temporarily shelter 1,000 Jewish refugees from across Southern and Eastern Europe through Italy. The politically risky plan would circumvent US immigration quota laws. The refugees would be allowed to enter the United States as long as they promised to return to their home countries after the war.

The WRB settled the 982 refugees that made the journey in Oswego, NY at Fort Ontario. Officials chose Fort Ontario, an 18th and 19th century military fort that served as a hospital and training center. In some ways it resembled the detention camps used by the government for German Prisoners of War on US soil. There were barbed wire fences, military patrols and curfews. In other ways, Fort Ontario offered Jewish refugees safety and a sense of community.

A condition of the refugees being allowed into the United States was a promise they would return to Europe when the war was over. After the war, however, refugees lobbied to stay. In 1946, President Truman granted them visas and many applied for citizenship.

Activity 2: Oral Histories - Life at Fort Ontario

In 1984, researchers conducted oral history interviews with former refugees. Many were children when they came to Fort Ontario. Their memories of their escape from Europe and their first year in America reveal the complicated, and often traumatic, situation they found themselves in. Have students listen to parts of the oral history. These excerpts focus on the first impressions of Fort Ontario. If time allows, encourage students to explore longer sections. All audio recordings and transcripts are from:

“Oral Histories: Emergency Refugee Shelter at Fort Ontario (Safe Haven). Special Collections, Penfield Library, SUNY Oswego. https://www.oswego.edu/library/safe-haven.

Break students into groups. Assign each group an excerpt from an interview to read and listen to. Groups should answer the following questions and then be prepared to discuss their excerpt with the class.

Group 1: Walter Greenberg, Tape 270, Tape 2, Side A. 19:54-23:05.

“Well, I remember traveling on this train and stopping at Fort Ontario. Getting out, and um . . . having lots of people to meet us. I must say that I was very shocked and surprised that there was a fence around the camp. Uh, I argued about the fence with many people, for many, many years. And before our reunion in 1981 in Syracuse, we debated whether the fence was barbwire or whether it was a different kind of a wire. And most people said it was a chicken wire fence. And I said that it was a barbwire fence. The realty was that it was really a chicken wire fence with barbed wire on top of it. For my reality and for Walter Greenberg’s reality, for me it was a confinement and there was a fence and I was on the inside looking out and there were people on the outside looking in. Now, Fort Ontario for me was a bittersweet experience for me. Because I had left worn [sic]-torn Italy and I had everything that I needed and wanted. I had food, clothing, doctors if I was sick. School, I may add, for the first time in my life. Wonderful people. But I felt strange. I felt deceived. But I didn’t know why because I was too young to understand it. I think that it’s very difficult to sit here, forty years later and to really . . . to say what you’d like to hear . . . I mean, I’m a mature adult, forty years later trying to understand how I felt then. I felt wonderful and I felt terrible. Okay. That’s what the camp meant to me.”

Group 2: Maurice Kahmi, Tape 269, Side A. 6:13-7:20 and 9:38-11:33.

“Of Oswego. Well, of course, Oswego was a fairy tale for all of us, and though there was a barbed-wire fence. It didn’t mean anything because we knew everything was just fine, people were fine. The girls came to the fence every evening to flirt with us because they liked foreign boys, and we loved that, of course. The only problem as far as I was concerned was that I had been starving during the whole war, so when we got to Oswego there was so much food and my mother happens to be a very good cook, she worked in the kitchen so she would bring home loads of food every night and I just couldn’t stop eating. I got as fat as a butterball. Aside from that, everything was just wonderful. We went to school. Of course we had to fight the American boys because they were angry that the girls were flirting with us, so there was a fight every single day, but nothing was serious and we had a wonderful time in Oswego.”

Group 3: Adam Munz: Tape 271, Tape A, Side 1. 30:51-31:50. Change to Side 2. 0-0:42.

“Yes, we did not expect to be as curtailed in our movements as we were. The first period was the quarantine; the gate was around the camp; we needed special passes and so on. I understand it now much better than I did then. Then it was difficult to fathom why a land that prides itself on total freedom felt the need to restrict movements of a group of harmless people. Eventually we were allowed to leave the camp to go to school and so on. It wasn’t that bad. Some, however, likened the experience of being surrounded by a fence and living in Army barracks to concentration camps. The similarities stopped, however, there… by and large. The authorities in the school made every special effort to accommodate to us. “After all we didn’t speak the language very well; many of us didn’t speak it at all. They made special arrangements of all kinds, made it as easy as one could make entry into a foreign culture, into a school system that was alien to us. Some of the townspeople were very pleasant too; others looked on us as strange animals, looked at us as intruders. After all, 982 people invading a small town like Oswego must have been a cataclysmic event. I’m sure some regarded it as a mixed blessing.”

Group 4: Manya Hartmeyer Breuer, Tape 270, Tape 2, Side A. 12:25-14:53.

“All of a sudden, I was brought back to the sun, to sunshine and life. And I faced the beautiful country that took me in, which I was forever grateful. We were brought to Oswego, New York, by train and when we entered the camp I had Ernest and Lisa Breuer with me and the first day we were issued towels and soap, which we hadn’t seen in so long. I have to tell you; my first breakfast consisted by seven eggs. I ate all the bananas that I could find. [Crying again.] And food was so precious to me and the freedom too. Freedom to look up and not be scared or afraid that someone was going to pick you up and kill you. The first day in Fort Ontario the refugees lined up, I remember that very well. We were in a long line; and we were almost at the end of the line. And I see a man sitting on a chair with a camera in front of him. He didn’t take any pictures, but when I came into the camera and focused, he starts snapping my picture. I thought he was a tourist. It turned out later on that it was Alfred Eisenstaedt who took our pictures for Life Magazine, later on. Uh, how can I describe to you our feelings? We had come a long way and I was young enough and old enough to remember and to compare how lucky indeed I was to be in Fort Ontario, in this camp. Although it was not exactly as we thought it would be, it was another camp, but I didn’t mind that at all. I was just, as I said before, starting to live again.”

Student Questions

-

What do you know about the speaker (from your knowledge of the project or from what they say in the interview)? How does their background influence how you think about them as a source?

-

Describe their experience at Fort Ontario.

-

Describe their feelings about Fort Ontario.

-

What background information do you know about World War II, refugees, the United States, etc. that might influence what you hear in the tapes? How does that impact how you interpret the narrative?

As a class, come back together and have representatives from each group share what they learned. Compare the oral histories as a class by discussing these questions:

-

The fence is a recurring theme in the testimony. What did the account you listened to say about the fence? How does that compare with other accounts? What do you think about the fence?

-

Fort Oswego as a “fairy tale” is another theme. Why do you think that is? How did the interview you listened to refer to it? In what context? How does that fit with the conversation in your and other accounts about the fence?

-

How were the emotions and framing in the response you listened to similar or different from what your classmates describe? What does that tell us about the way people felt at the time and how they remember Fort Ontario today?

Wrap Up

-

How was the experience of Jewish Refugees to Ft Ontario similar and different to immigrant experiences (either at the time or from previous eras in history that you may have learned about)?

-

To what extent did the refugee placement at Ft. Ontario meet the mandate of the War Refugee Board and Executive Order 9417?

- How do you feel the United States should act in regards to refugees? To immigrants? What distinctions, if any, would you make?

Additional Resources

“Haven from the Holocaust” is a 1 hour radio documentary about Fort Ontario. The oral histories in this lesson were collected in part for this production and the program is a way to hear multiple perspectives and a larger narrative from Jewish refugees’ experiences.

“Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter” bibliography and article from the United States Holocaust Memorial to learn more and get additional resources.

The “Final Summary Report of the Executive Director, War Refugee Board” from September 15 1945, offers a primary source assessment of the successes and failures of the WRB more generally and, on pg 64-69, Ft Ontario in particular.

To see more great photographs and explore more current reflections on this history, read this New York Times article from 2020.

This lesson was written by Alison Russell.

Tags

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- world war ii

- wwii

- wwii home front

- religion

- religion and wwii

- judaism

- jewish history

- jewish heritage

- new york

- military history

- immigration

- migration and immigration

- refugee

- refugee camp

- women and migration

- franklin delano roosevelt

- harry s truman

- hour history lessons

- lesson plan

- teacher resources

- twhplp

- women's history