Part of a series of articles titled Claiming Civil Rights .

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Fit for Service, Colonel Charles Young’s Protest Ride

This lesson was adapted by Katie McCarthy from the Lesson Teaching With Historic Places Lightening Lesson “Discover Colonel Young’s Protest Ride for Equality and Country.”

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for middle school learners but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives:

Students will be able to...

-

Describe how racism affected African American service men in the early 20th century and how Colonel Charles Young persevered through it.

-

Describe how racism before and after WWI impacted the fight for civil rights.

-

Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose.

-

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

Inquiry Question:

This picture shows the route Colonel Charles Young followed as he rode by horseback from Ohio to Washington D.C. Why do you think Colonel Young chose to make the trip to D.C. on horseback, instead of by train or car? What do you think could have motivated him to take such a journey?

as he rode horseback from Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. in June 1918.

Background:

When the United States entered World War I, racial segregation was entrenched in military culture as well as civilian society. Segregation enforced barriers that prevented African Americans from enlisting. Despite this, about 380,000 African Americans served in the U.S. military during the war.

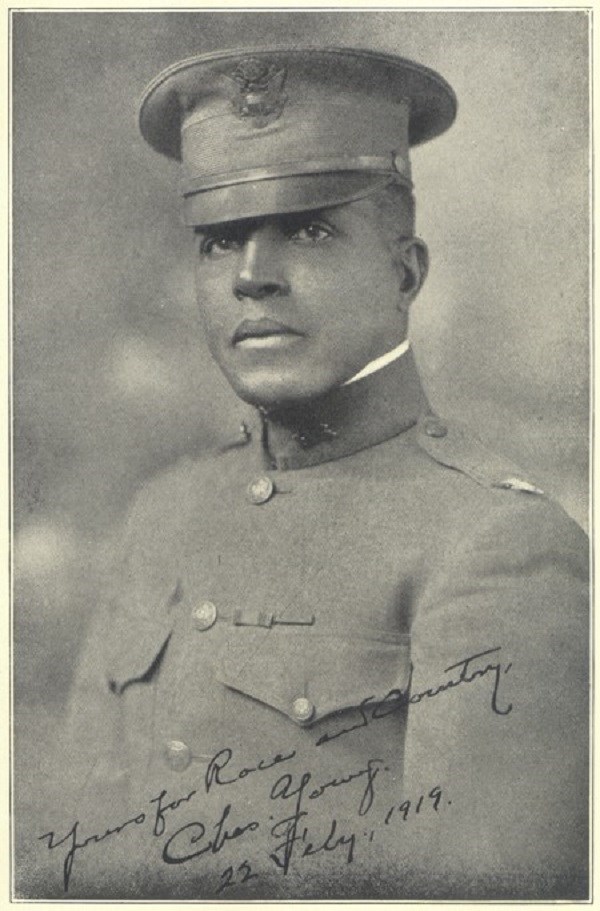

Colonel Charles Young was the highest-ranking African American Army officer in 1918. Despite an impressive leadership record, the Army refused Young’s request to command troops in Europe. Military leaders told him he was not healthy enough to serve.

To prove his fitness, Young made a difficult ride on horseback from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio to Washington, D.C. His brave display failed to persuade the Secretary of War. Young did not lead soldiers in Europe, but he fought for respect on the Homefront.

Reading:

Charles Young was born in May's Lick, Kentucky in 1864. His parents, Gabriel and Arminta, were enslaved at the time, making him enslaved at birth. His father escaped in 1865 and enlisted in the Union Army. Gabriel Young served in the 5th United States Colored Heavy Artillery. The family moved to Ripley, Ohio, after the war. As a boy, Charles Young was influenced by the town’s culture of activism and self-improvement. In many southern states prior to the Civil War, it was illegal for enslaved people to learn to read in write. However, Charles Young’s mother and grandmother could both read and write. Their example inspired Young to be a dedicated student. As a young man, Charles Young applied to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point after attending local schools. He became one of the first ten African Americans admitted to West Point.

During his career, Young served with the segregated 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments. Young led African American troops in Cuba, Haiti, the Philippines, Mexico, Africa, and in the western United States. Colonel Charles Young was the first African American superintendent of a National Park as an Army officer patrolling Sequoia National Park in California one summer. Under Young and other leaders, African American troops were some of the first U.S. government employees to work in National Parks.

Alongside his Army service, Young taught military science at Wilberforce University in Ohio. As a teacher, he worked with other important African American thinkers and scholars like W.E.B. DuBois and Paul Laurence Dunbar. An activist and historian, DuBois included Colonel Young’s achievements in his writings about Black history. Dunbar was a poet and playwright, and Young composed music for Dunbar’s verses.

Colonel Young married a woman named Ada Mills in 1904. In 1907, Colonel and Mrs. Young bought a house near the university in Wilberforce. They called it “Youngsholm.” Ada lived here with their two children, Marie and Charles Noel. Their historic house was built around 1839 and was a station on the Underground Railroad. Today, both Wilberforce University and Young’s house are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The First World War began in 1914, but the United States did not join until April 6, 1917. When the U.S. did go to war, African Americans were eager to serve in the military. Many volunteered. However, in a segregated society, some people asked: who would lead the African American troops in Europe? Would the leaders be men of color or would they be white? At age 53, Colonel Young was the highest-ranking African American military officer in the United States at the time. He and his supporters believed he should lead these soldiers.

However, Army officials did not agree. In June 1917, the Army promoted Charles Young to the rank of Colonel but declared that he was physically unqualified to lead troops in World War I. Colonel Young did not accept this. He believed it was his duty to lead troops in France. Colonel Young objected formally and sent documents to show he was healthy. From his home in Ohio, he tried to appeal to the senior officials in government and asked them to change their minds, but he could not persuade them.

After a year of arguing his case, Colonel Young mounted his horse in Wilberforce on June 6, 1918, and began a difficult 16-day ride to Washington D.C. He rode horseback for 497 miles. Today, if you followed Colonel Young’s route in a car, you would drive for almost eight hours. On horseback, it took Colonel Young two weeks to cross through Ohio, West Virginia, Maryland, and Virginia to get to Washington D.C. Young completed his ride on June 22 when he arrived in the District of Columbia. He was tired and worn but healthy. In the capital, Young met with the Secretary of War, Newton Baker. The Secretary did not change his mind even after seeing proof that Young was physically fit and able to command. After a lifetime of bravery and leadership, and after a great show of strength, Colonel Young still could not persuade the U.S. Army to give him a command in Europe.

Colonel Young continued to serve in the Army despite discrimination and barriers to the positions he wanted. The Army assigned him to a unit in Liberia, a country in Africa with ties to the United States. Americans founded it in 1847 to be a new home for free African Americans. Colonel Young died in Liberia on January 8, 1922 and the Army buried him in Arlington National Cemetery. This cemetery is located in Arlington, Virginia, right across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The United States reserves it for American soldiers and individuals like presidents, senators, and diplomats.

Colonel Young's ride showed his strength, his patriotism, and his ability to stand against the odds. He challenged people who considered themselves superior to him because of their race. He was an exceptional person, but he was not alone in this case. Many African American World War I soldiers dealt with racism in the Army. They also faced it when they returned home. Several African American World War I soldiers were lynched (murdered by a mob without a trial) after the war. This kind of terrorism was widespread in the United States after the war. In 1919, lynch mobs murdered 77 African Americans and legal segregation lasted for over forty more years. The conditions they faced during this era led up to the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Questions for Reading 1: “The Life and Service of Colonel Charles Young”

-

Who was Colonel Charles Young? In your own words, describe in a short paragraph why Young is an important person to study in history.

-

Do you think Colonel Charles Young was qualified in 1917 to lead troops in Europe during World War I? List three events from his life in the United States that may have prepared him for this work and briefly explain how those events prepared him.

-

In two sentences, explain in your own words why Colonel Young rode from Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. What do you think motivated him? Why?

-

Youngsholm is preserved as evidence of Young’s life. From the essay, what other places might have evidence of Young’s life? What might you be able to learn about them by studying that place?

Activities:

In each of these activities, participants engage critically and analytically with Colonel Young’s ride from Ohio to D.C. In the first, learners analyze newspaper accounts of the event for potential bias. In the second, participants create a map from their location to Washington, D.C. Educators should choose one of the following activities to complete with their learners.

Activity 1: Analyzing Primary Sources

In this activity, participants explore two accounts of Colonel Young's ride and then explore how reporters’ perspectives, including bias and the assumptions they make about their audience, influence the historical record. This activity has two parts. In the first, participants compare and contrast two historic newspaper articles about the same event to identify potential biases. In the second, students identify two newspaper articles about a current day event and analyze them for bias.

First, provide learners with a copy of the primary sources below. Ask them to identify similarities and differences in the two accounts published in leading African American publications, the Cleveland Advocate and the nationally-read paper, The Crisis. As they read, have students consider the following questions:

-

Who is this newspapers primary audience? What this their relation to Colonel Young?

-

What is the overall message of this article?

-

What emotions or feelings might this article inspire in its readers?

Then, guide a class discussion to go over their observations or have students write down their compare/contrast observations as lists.

Col. Young Rides to Capital on Horseback

Washington's Colored population was agreeably surprised today with the arrival of Colonel Charles Young, who came all the way from Wilberforce, Ohio, his home a distance of 650 miles [sic], on horse back and foot. The Colonel looks fit for an endurance hike or for service at the front. The restoration to active duty in this war, of the race's senior army officer, it is believed by race men here, would remove one source of unrest within the race.

Source: Taylor, Ralph. "Col. Young Rides to Capital on Horseback." Cleveland Advocate, June 29, 1918, p. 4.

[Editor’s note: The Cleveland Advocate was a weekly Republican paper focusing on local and national news that were of interest to African Americans.]

The Horizon, a news bulletin taken from The Crisis

Colonel Charles Young in order to test his physical fitness made a trip from Xenia Ohio, to the National Capital on horseback, a distance of 497 miles. He arrived in first class condition in sixteen days.

Source: "The Horizon: The War." The Crisis, August 1918, Vol. 16, No. 4, p. 187.

Next, have participants explore the concept of unintended or implicit bias in news reporting further. Ask your learners to search an online database of recent newspapers to find two news articles from different publications about current events. They should save or print out the two documents, study them, and be prepared to compare and contrast them.

Ask participants to theorize why the accounts are different, using examples from their classroom work and personal experiences, and how assumptions made in news reporting might affect the work of historians. Ask them to give an example of how a historian might solve problems with using news articles to study history.

With their articles and study, students can write a one-page analysis to answer these questions or give a short oral presentation to the class.

Activity 2: Create a Map

In order to safely travel from Wilberforce, Ohio to Washington D.C., Colonel Young had to carefully map out his route. If you were to travel by horseback from your house to Washington D.C., how long would it take you? How many stops would you have to make? Assuming that you can only travel 30 miles at a time, carefully map out a route. Make sure to pay attention to where you can stay overnight, especially if you don’t want to be stuck camping on the side of the road! When you’re done, draw out your route on a physical or digital map.

Wrap-up:

-

What do you think motivated Colonel Charles Young to make the trip to Washington D.C.?

-

How do you think Colonel Charles Young felt at different points during his life and career? When is a time when you felt like that?

-

Why might actions such as Colonel Charles Young matter to you and your community? Why is it important that we learn about it?

-

Can you think of any parallels to Colonel Charles Young’s story in our country today?

Additional Resources:

National Park Service

The National Park Service manages the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument in Wilberforce, Ohio, the historic home of Colonel Charles Young and his family. It is open to the public and offers a museum, guided ranger tours, and an archive.

Ohio History Connection

The Ohio History Connection's The African American Experience in Ohio 1850- 1920 offers free access to 100+ primary sources from the life of Colonel Charles Young, including creative writing, military documents, and letters from family and individuals like W.E.B. Dubois, R.R. Moton, and Booker T. Washington. Young’s letters relate his own thoughts about experiencing racism, including racism in school and in the Army. The same collection of African American history includes the Ralph Tyler Collection. Tyler was an African American WWI war correspondent and his articles chronicle African American life during World War I.

The United States World War One Centennial Commission

The US WWI Centennial Commission's mission is in part to educate Americans about the World War. Its robust website provides teachers and facilitators with lessons, timelines, and interactives to support student exploration and curricula. The website has a searchable teaching resource database.

The Modernist Journal Project

Formed through a Brown University / University of Tulsa partnership, the project

provides digitized copies of the NAACP’s The Crisis (1910 -1922). The collection is a trove of information on African American World War I soldiers, including Charles Young.

Last updated: May 9, 2023