Part of a series of articles titled On Their Shoulders: The Radical Stories of Women's Fight for the Vote.

Article

“All Men and Women Are Created Equal:” The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton

By Lori D. Ginzberg

Elizabeth Cady was born in Johnstown, New York, to a conservative, slave-owning family that held conventional ideas about women’s place; that experience – of both privilege and exclusion – shaped her thinking. Decades later she recalled that when, at age eleven, she sought to comfort her father for the loss of his son, Judge Daniel Cady sighed that he wished she had been a boy.[1] And although she received the best education available to girls at Emma Willard’s Troy Female Seminary, she fumed that she had been consigned to something merely “fashionable.”[2] The young Elizabeth turned those resentments into a broad and sweeping battle against women’s exclusion from the educational, legal, and political rights of men.

The personal and the political came together when Elizabeth Cady met the antislavery lecturer Henry Brewster Stanton at her radical abolitionist cousin Gerrit Smith’s home. The two married in 1840 and set sail for London, where Henry was a delegate to the World Antislavery Convention. There Elizabeth witnessed female abolitionists, including Lucretia Mott, being rejected as delegates, and a few men, notably William Lloyd Garrison and Charles Lenox Remond, joining them in protest. Eight years later, now a mother of three small boys in the village of Seneca Falls, eager to use her intellectual powers and focus her discontent, she, Mott, and several other friends convened a convention in Seneca Falls, New York.

Still, the “Declaration of Sentiments” that Stanton and her friend Elizabeth McClintock wrote and presented and the convention subsequently adopted is extraordinary. Adopting the pattern of the Declaration of Independence, it asserted that “All men and women are created equal” and held “mankind” responsible for women’s exclusion from the nation’s revolutionary promise. While the vote has come to be seen as the convention’s central demand, the Declaration of Sentiments listed numerous “repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman”: the laws of marriage that “compelled [wives] to promise obedience to her husband,” denied her the right to inherit or control property and, in cases of divorce, her children; the restrictions against women entering “all the profitable employments;” religious teachings that silenced her; social norms that created a double standard of morality; and a society that sought to “destroy her confidence in her own powers.” Stanton’s mission was to change all that and to ensure that women would be considered equal and independent citizens alongside men.

For the next half century, alongside Susan B. Anthony (whom she met in 1851), Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote, spoke and agitated on behalf of woman’s rights including, but never limited to, the vote. In many ways she lived a conventional life. She was a married woman and the mother of seven children, whose public work was made possible by a housekeeper, Amelia Willard. But if her life could seem sedentary, she was always in intellectual motion, and she longed for a larger sphere of action. “Men and angels give me patience!” she wrote a friend in 1852. “I am at the boiling point! If I do not find some day the use of my tongue on this question, I shall die of an intellectual repression, a woman’s rights convulsion!”[3]

Stanton’s demand for the vote was based on the simple idea that individuals should not be denied the rights of citizens simply on the basis of sex. Still, her appeals to universal justice were infused with racism and class prejudice. As early as 1848, when the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments protested that women were denied rights that were given to “the most ignorant and degraded men – both natives and foreigners,” Stanton’s sense of entitlement as an educated, white, native-born woman shaped her priorities.

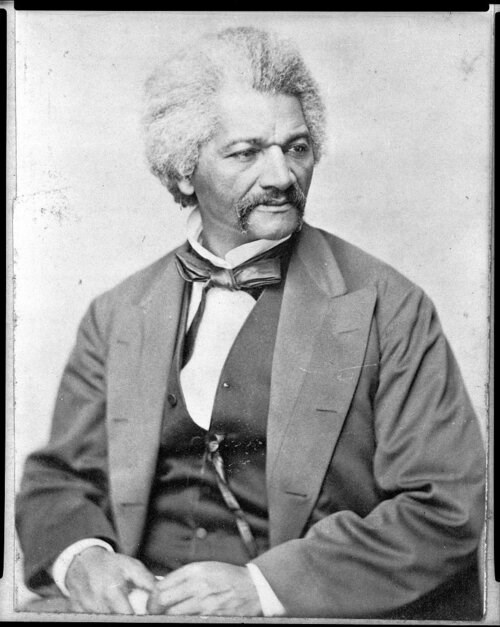

Stanton’s prejudices became especially visible – and divisive – immediately after the Civil War. In the late 1860s, many abolitionists, among them Lucy Stone and Frederick Douglass, who had long advocated for women’s rights, joined Radical Republicans in arguing that there was greater urgency in gaining the vote for African-American men than for women. Stanton and Anthony were outraged. Declaring themselves the defenders of universal liberty, they nevertheless resorted to the view that some people were better suited to exercise political rights than others. If suffrage is to be extended gradually, Stanton insisted, “it would be wiser and safer to enfranchise the higher orders of womanhood than the lower orders of black and white, washed and unwashed, lettered and unlettered manhood.”[7] With the end of the abolitionist and women’s rights coalition after the Civil War, an independent women’s suffrage movement emerged in 1869 that was made up of two competing organizations; Stanton and Anthony led the National Woman Suffrage Association for much of the rest of their lives.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an absolutist, for better or worse, and she remains a controversial figure, larger than life, brilliant, charismatic, and confident. Many in her own time considered her a dangerous radical, whose insistence on women’s complete legal, political, and religious equality with men threatened to turn the world upside down. Others, including thousands of women who heard her speak, thought Stanton a thrilling lecturer, someone who turned their frustrations as daughters, wives, and mothers, and their exclusion from the full rights of Americans, into a platform for action. And while Susan B. Anthony came to be most closely associated with the vote, Stanton would come to embody the idea that the “personal is political” to many feminists of the 1970s. This analysis, which moved beyond claims to political and legal equality to include critiques of marriage, motherhood, and domestic violence, insisted upon women’s full emancipation from the constraints society imposed on their sex.

Historians too have found Stanton complex and often contradictory. Although virtually all scholars acknowledge, and regret, Stanton’s bigoted rhetoric, they differ about how much her elitism and racism reflect a deep vein in her thought. Some consider Stanton’s elitism common to her era and class, which it surely was; some believe that Stanton’s bigotry represented a strategic decision made under difficult political circumstances. But many argue that Stanton’s priorities narrowed her very definition of women’s rights to those that white, middle-class women most fervently sought, and, to a large extent, gained. To Stanton, gaining the vote would establish women such as herself – educated, native born, and white – as independent citizens alongside men. In contrast, African American, working-class, and immigrant women often viewed the vote less as a symbol than as a tool, one their communities needed desperately to advance economically, to demand protection from violence, and to assert their right to be heard. Unable to recognize this perspective as a legitimate challenge to the ideals of liberal individualism, Stanton’s racism reflected a serious failure of her radical imagination. All, however, would likely agree with Stanton who, having promoted educational, economic, marital, and political rights for women, declared, "This sounds like a very radical proposition now, but be sure that someday in the future Americans will ask how these things could ever have been done otherwise."[9]

Author Biography

Lori D. Ginzberg is a professor of History and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Penn State University. She is the author of several books, including Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York (Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2005) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2009). She has been the recipient of numerous awards, including fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and the Huntington Library. In the summer of 2017 she taught an NEH summer seminar for K-12 teachers in Philadelphia on the topic “What Did Independence Mean for Women? 1776-1876.” This year she will be speaking throughout the country, as well as on radio and in podcasts, about Elizabeth Cady Stanton and about the complexities and challenges of historic commemoration. Lori Ginzberg lives in Philadelphia.

Footnotes

[1] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eighty Years and More: Reminiscences 1815-1897 (NY: Schocken Books, 1971; reprinted from T. Fisher Unwin edition, 1898), p. 20.

[2] Ibid, p. 35.

[3] Stanton to Susan B. Anthony, April 2, 1852, in Theodore Weld Stanton and Harriot Stanton Blatch, eds., Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Selected Letters (NY: Harper and Brothers, 1922), 2:41-42.

[4] Stanton, Eighty Years and More, p. 201.

[5] For an excellent discussion of the Women’s Bible see Kathi Kern, Mrs. Stanton’s Bible (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2001).

[6] Stanton to Martha Coffin Wright, [May 28], 1860, in Stanton and Blatch, eds., ECS 2:80-81.

[7] Stanton, “Female Suffrage Committee,” [June 19, 1867], in Ann D. Gordon, ed., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: Volume 2: Against an Aristocracy of Sex, 1866-1873 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2000), 2:72-73.

[8] Stanton to Clara Colby, June 16 [1890], Patricia Holland and Ann D. Gordon, eds., The Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources 1991), microfilm reel 28.

[9] Stanton to Martha Coffin Wright, Feb. 10, 1861, in Stanton and Blatch, eds., ECS 2:87.

Selected Bibliography

Barkley Brown, Elsa. "Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom." Public Culture 7 (1994): 107-146.

DuBois, Ellen Carol and Richard Cándida Smith, eds. Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Feminist as Thinker: A Reader in Documents and Essays. New York: NYU Press, 2007.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848-1869. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

Dudden, Faye E. Fighting Chance: The Struggle Over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage jn Reconstruction America. NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 2014.

Ginzberg, Lori D. Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Ginzberg, Lori D. Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life. NY: Farrar, Straus Giroux, 2009.

Hoffert, Sylvia D. When Hens Crow: The Woman's Rights Movement in Antebellum America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Jones, Martha S. All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2007.

Kern, Kathi. Mrs. Stanton’s Bible. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Kerr, Andrea Moore. Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995.

Lutz, Alma. Created Equal: A Biography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. New York: John Day Company, 1940.

Stanton, Henry B. Random Recollections (1887: HBS died while revising this 3rd edition)

Stanton, Theodore Weld and Harriot Stanton Blatch, eds. Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Selected Letters. NY: Harper and Brothers, 1922.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. press, 1998)

Tetrault, Lisa. The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898. Chapel Hill: Univ of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman's Rights Convention. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Lori D. Ginzberg is a professor of History and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Penn State University. She is the author of several books, including Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York (Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2005) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2009). She has been the recipient of numerous awards, including fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and the Huntington Library. In the summer of 2017 she taught an NEH summer seminar for K-12 teachers in Philadelphia on the topic “What Did Independence Mean for Women? 1776-1876.” This year she will be speaking throughout the country, as well as on radio and in podcasts, about Elizabeth Cady Stanton and about the complexities and challenges of historic commemoration. Lori Ginzberg lives in Philadelphia.

Footnotes

[1] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eighty Years and More: Reminiscences 1815-1897 (NY: Schocken Books, 1971; reprinted from T. Fisher Unwin edition, 1898), p. 20.

[2] Ibid, p. 35.

[3] Stanton to Susan B. Anthony, April 2, 1852, in Theodore Weld Stanton and Harriot Stanton Blatch, eds., Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Selected Letters (NY: Harper and Brothers, 1922), 2:41-42.

[4] Stanton, Eighty Years and More, p. 201.

[5] For an excellent discussion of the Women’s Bible see Kathi Kern, Mrs. Stanton’s Bible (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2001).

[6] Stanton to Martha Coffin Wright, [May 28], 1860, in Stanton and Blatch, eds., ECS 2:80-81.

[7] Stanton, “Female Suffrage Committee,” [June 19, 1867], in Ann D. Gordon, ed., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: Volume 2: Against an Aristocracy of Sex, 1866-1873 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2000), 2:72-73.

[8] Stanton to Clara Colby, June 16 [1890], Patricia Holland and Ann D. Gordon, eds., The Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources 1991), microfilm reel 28.

[9] Stanton to Martha Coffin Wright, Feb. 10, 1861, in Stanton and Blatch, eds., ECS 2:87.

Selected Bibliography

Barkley Brown, Elsa. "Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom." Public Culture 7 (1994): 107-146.

DuBois, Ellen Carol and Richard Cándida Smith, eds. Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Feminist as Thinker: A Reader in Documents and Essays. New York: NYU Press, 2007.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848-1869. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

Dudden, Faye E. Fighting Chance: The Struggle Over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage jn Reconstruction America. NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 2014.

Ginzberg, Lori D. Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Ginzberg, Lori D. Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life. NY: Farrar, Straus Giroux, 2009.

Hoffert, Sylvia D. When Hens Crow: The Woman's Rights Movement in Antebellum America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Jones, Martha S. All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2007.

Kern, Kathi. Mrs. Stanton’s Bible. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Kerr, Andrea Moore. Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995.

Lutz, Alma. Created Equal: A Biography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. New York: John Day Company, 1940.

Stanton, Henry B. Random Recollections (1887: HBS died while revising this 3rd edition)

Stanton, Theodore Weld and Harriot Stanton Blatch, eds. Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Selected Letters. NY: Harper and Brothers, 1922.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. press, 1998)

Tetrault, Lisa. The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898. Chapel Hill: Univ of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman's Rights Convention. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Last updated: December 14, 2020