Last updated: March 30, 2023

Article

"The Electric Project": The Minidoka Dam and Powerplant (Teaching with Historic Places)

(Bureau of Reclamation)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

The big green generators are quiet now. For almost 90 years, their roar filled the old powerplant on the Bureau of Reclamation's Minidoka Irrigation Project all day, every day. The plant put the Snake River to work turning the power of falling water into electricity. The electricity was needed to pump irrigation water up to thousands of acres of sagebrush desert in southern Idaho.

The powerplant was also a step in the expansion of Reclamation's mission. The Reclamation Act of 1902 gave Reclamation just one job. That job was to bring irrigation water to the arid "American desert." By the late 1920s, the bureau's mission also included providing critical hydroelectric power to the rapidly growing cities and states of the West. Minidoka's powerplant represents that change toward an expanded mission. Not only did the powerplant supply power to run the irrigation system, it also brought electricity to people living in the towns and on the farms on the project. Minidoka settlers enjoyed the "magic force" of electricity at a time when more than 98 percent of American farmers had to do without such luxury.

The Secretary of the Interior approved construction of the Minidoka Project in 1904 to bring irrigation water to 120,000 acres of arid land lying north and south of the Snake River. The project facilities to be built included a long, low dam, a large reservoir, a complex system of canals, and a powerplant. Today, the Minidoka Project includes seven dams and thousands of miles of canals bringing water to more than a million acres of productive farmland. A second powerplant was completed at Minidoka Dam in 1997.

Reclamation is now the second largest producer of hydroelectricity in the United States. The bureau operates 53 powerplants, and delivers irrigation water to 140,000 farmers on 10 million acres of farmland, as well water for various uses to towns and cities.

About This Lesson

The Minidoka Dam and Powerplant is individually listed in the National Register of Historic Places. This lesson uses information from the National Register of Historic Places documentation entitled "Minidoka Dam and Powerplant" (with photos); a report entitled "Minidoka Dam, Powerplant and South Side Pump Division," prepared by Fraserdesign and Hess Roise and Company for the Bureau of Reclamation; the book Dams, Dynamos, and Development: The Bureau of Reclamation's Power Program and Electrification of the West, by Toni Rae Linenberger with initial assistance from Leah S. Glaser; and other Reclamation publications. The lesson was written by Marilyn Harper, historian, and edited by Teaching with Historic Places and Reclamation staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, geography, government, and civics courses, in units on the Progressive Era, history of the West, cultural geography, science, or the history of technology.

Time period: Early to mid-20th century

Relevant United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

"The Electric Project": The Minidoka Dam and Powerplant relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

-

Standard 1B - The student demonstrates understanding of Progressivism at the national level.

-

Standard 3B - The student demonstrates understanding of how a modern capitalist economy emerged in the 1920s.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

"The Electric Project": The Minidoka Dam and Powerplant relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity, and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

-

Standard C - The student uses appropriate resources, data sources, and geographic tools such as aerial photographs, satellite images, geographic information systems (GIS), map projections, and cartography to generate, manipulate, and interpret information such as atlases, data bases, grid systems, charts, graphs, and maps.

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard E - The student locates and describes varying land forms and geographic features, such as mountains, plateaus, islands, rain forests, deserts, and oceans, and explains their relationships within the ecosystem.

-

Standard F - The student describes physical system changes such as seasons, climate and weather, and the water cycle and identifies geographic patterns associated with them.

-

Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land uses, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

-

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard F - The student describes the role of institutions in furthering both continuity and change.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard I - The student gives examples and explains how governments attempt to achieve their stated ideals at home and abroad.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

-

Standard A - The student gives and explains examples of ways that economic systems structure choices about how goods and services are to be produced and distributed.

-

Standard C - The student explains the difference between private and public goods and services.

Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

-

Standard B - The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationship to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants, and security.

-

Standard D - The student explores the causes, consequences, and possible solutions to persistent, contemporary, and emerging global issues, such as health, security, resource allocation, economic development, and environmental quality.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard D - The student practices forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

Objectives for students

1) To describe the construction and early history of the Minidoka Project and Powerplant,

2) To explain the creation and development of electric power on the Minidoka Project and changes in the hydropower program of the Bureau of Reclamation as a whole,

3) To describe how the availability of electricity changed the lives of people living on the project,

4) To list the steps in turning falling water into electric power,

5) To prepare an exhibit or other interpretive product on power-related resources in the students' local area.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

1) One map, showing the arid West;

2) Three readings, about the history of the Minidoka Project, on the development of hydropower on the project, and on how project settlers used electricity in their daily lives;

3) Two illustrations, one schematic drawing of a hydroelectric generator and one drawing showing the Minidoka Project; and

4) Five photos including four historic images of the Minidoka Powerplant, life on the project, and the project landscapes.

Visiting the site

The Minidoka Project is located on either side of the Snake River in southeast Idaho. The project's irrigated fields are visible from Interstate 84/86 in the area around the towns of Rupert and Burley and from a number of state highways and local roads accessible from the Interstate. The fields are private property and not open to visitors.

During World War II, the Minidoka Relocation Center was established on Minidoka Project land. It housed more than 7,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, most of them American citizens, relocated from their homes on the West Coast as the result of post-Pearl Harbor hysteria. The Minidoka Relocation Center is now a National Historic Site, administered by the National Park Service. For more information and directions, please consult the website for the historic site.

Birders will enjoy Minidoka National Wildlife Refuge, on the shore of Lake Walcott. Campers and boaters are welcome at Lake Walcott State Park.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Bureau of Reclamation, Photo by Barry Dibble)

Locating the Site

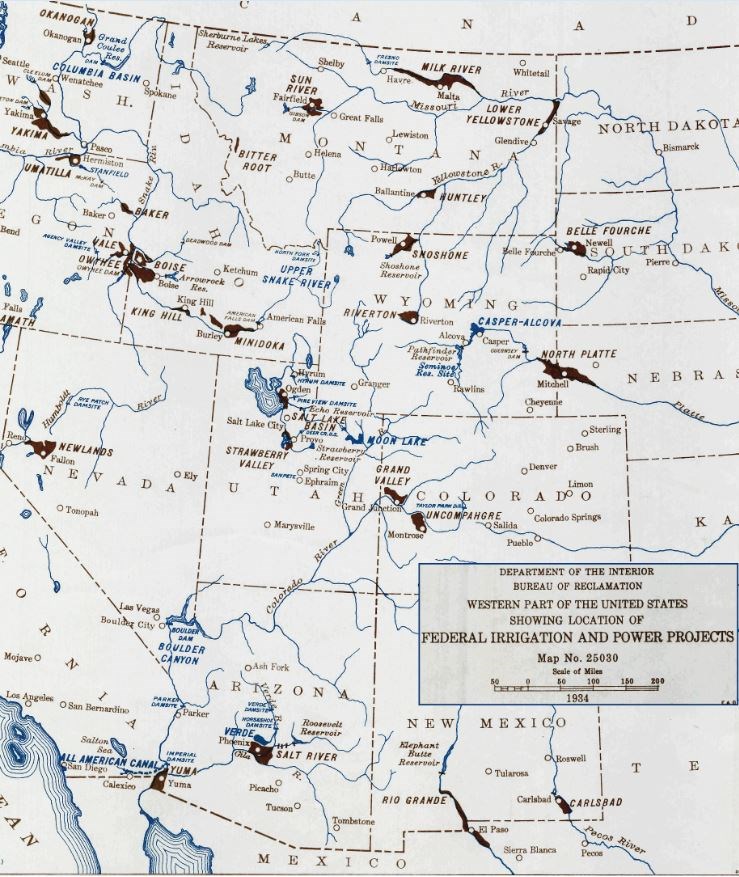

Map 1: Federal Irrigation Projects, 1934.

(National Archives and Records Administration)

Early 20th Century irrigation projects are shown in brown. New irrigation and power projects approved by 1934 are shown in blue.

Questions for Map 1

1) Find the Minidoka Project, an early project in Idaho, near Burley. Use the map scale to estimate how long the brown area is between its eastern and western ends. How wide is it at its widest point? Can you think of any comparison that might help you get a sense of how big this project actually is?

2) Find the Snake River. Where does it start? Where does it end?

3) How many other early projects can you find? What states are they in? Can you identify any geographical feature that the projects have in common?

4) What kind of climate do you think the regions with projects might have? Why do you think so?

5) How do you think irrigation might help people living on a project?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Minidoka Project

Congress passed the Reclamation Act in 1902. President Theodore Roosevelt signed it the same day it appeared on his desk. The Reclamation Act was one of the first laws passed after Roosevelt became the president. It was also one of the first important laws passed during the Progressive Era. Roosevelt sent a letter to the Secretary of the Interior when he signed the Act into law. In it, he said: "I regard the irrigation business as one of the great features of my administration and take a keen personal pride in having been instrumental in bringing it about."1

The Reclamation Act directed the Federal Government to build irrigation projects. These projects would bring water to the arid lands of the West with dams and canals. The money to build the projects would come from the sale of federally-owned lands in 16 western states and territories. That money would be put into a newly created "Reclamation Fund."2 The settlers on an irrigation project would have to repay the construction cost once the project was complete. That money would go back to the Reclamation Fund and be used to build new projects. Each settler on a federal irrigation project could claim no more than 160 acres. This was because the vision for federal irrigation was to turn the desert into small family farms.

The Reclamation Act assigned responsibility for building and operating the irrigation projects to the Secretary of the Interior. He promptly created the U.S. Reclamation Service, a branch of the U.S. Geological Survey, to design, build, and operate the irrigation systems. The U.S. Reclamation Service became an independent agency within the Department of the Interior in 1907, and was renamed the Bureau of Reclamation in 1923. The term "Reclamation" is used throughout this lesson to refer to both the U.S. Reclamation Service and the Bureau of Reclamation.

Reclamation engineers immediately began to look for possible sites for irrigation projects. They soon found a good place for a dam at Minidoka Falls on the Snake River in southern Idaho. One hundred and twenty thousand acres of largely vacant land lay on either side of the river. The location was perfect for an irrigation project. The soil was fertile, but the area only got about 12 inches of rain a year. This is not enough for farming unless it is irrigated. The Secretary approved construction of the Minidoka Project in 1904. It was the seventh project approved since the Reclamation Act was passed. It was the first federal irrigation project in Idaho.

Some privately developed irrigation existed in southern Idaho by 1904. Ranchers irrigated hay fields and pasture on land along streams. A number of small irrigation companies were providing water to irrigate farms close to the Snake River and along other southern Idaho streams. However, most settlers and private companies did not have enough money to build dams or complicated irrigation systems. One exception was the Twin Falls Canal Company. In 1902 that company began work on an irrigation project near the town of Twin Falls, about 50 miles west of where Minidoka Dam would be built. The company began to deliver irrigation water in 1905. The enterprise was an immediate success. That helped attract settlers to Reclamation's irrigation project.

The first visitors to the Minidoka area remembered it as an uninhabited sagebrush desert. Reclamation's first step in turning the dry land into farms was to build Minidoka Dam. The dam would hold back the water of the Snake River to create a large reservoir. It would be an earthfill dam, with a long concrete spillway. The dam, which still stands today, is 736 feet long, 86 feet tall, and up to 412 feet wide at the base. The spillway extends another 2,400 feet to the south from the dam. This long spillway was needed to pass floodwaters. In total, the dam and spillway is 4,475 feet long. The first step to build the dam was to cut a diversion channel on the north bank of the river, with a concrete structure at its upper end. During dam construction the river was turned into this diversion channel. This left the river channel dry so that the men building the dam could work in safety. When the dam and spillway were finished, the concrete diversion structure became the lower level of the powerplant.

Water stored in the new reservoir flowed to the fields through two main canals, one built on either side of the river. Hundreds of miles of smaller canals and ditches carried water from the main canals to the farms. The canals and ditches work the same way today. The project contains both low-lying lands near the river and higher ground to the south. The low-lying land consists of nearly 60,000 acres north of the river (known as the North Side Gravity Division) and 10,000 acres on the south (the South Side Gravity Division). Water can flow to these low-lying lands using only the force of gravity. However, gravity-fed canals could not deliver water to the 50,000 acres of higher land south of the river (the South Side Pumping Division). Those lands are on terraces that sit at a higher elevation than the river, and water cannot flow uphill. Reclamation decided to use electric-powered pumps to "lift" water up to the higher terraces. Three pumping stations were built on the Main South Side Canal. One pumping station is on each terrace to raise the water up to the next higher terrace. On each terrace, water can then flow using gravity alone through canals and ditches to the farms. Minidoka Powerplant was built to generate the electricity needed to operate the pumps.

Minidoka Dam was completed in 1906. The Gravity Division canals were completed in the winter of 1907/1908. Construction of the powerplant and the three pumping stations began in 1908 and finished in 1909. Reclamation installed the first power generating unit in the powerplant as soon as the building was finished in 1909. They also installed one pump in each pumping station. The last of the original five power units was installed in the powerplant in 1911. The powerplant was designed to allow more power units to be added in the future, if more electricity was needed. Reclamation often designed dams and powerplants to allow for future growth. The Minidoka Powerplant was the first federal powerplant in Idaho. After 1911, it generated the most electricity of all powerplants in the state.

The early years on the Minidoka Project were hard for those living there. The son of an early settler once called life there a "matter of survival."3 It was difficult because homesteaders began to file Homestead Act claims for project land in 1904, even before Reclamation began building the dam. But farmers on the gravity divisions did not start getting irrigation water until 1908. Those on the Pumping Division had to wait even longer. A lucky few received water in 1909, and by 1911, about 20,000 acres of the Pumping Division had water. While waiting for the water, settlers still had to complete actions to meet Homestead Act requirements. They had to clear the sagebrush and prepare the land to be farmed. They also had to build a house and live in it. These activities required money for building supplies or to hire help with doing that work. Many homesteaders gave up and abandoned their claims because they didn't have enough money to make these improvements and feed their families while waiting for the water to arrive.

Things were not easy even after the water came. Although fertile, the soil was sandy and difficult to farm. Many settlers had never before practiced irrigated agriculture, and some had never farmed at all. Settlers who had never tried irrigated farming were most likely to leave. The homesteaders who remained on their farms could not grow enough crops to make a profit until about 1916. Yet they still had to make annual payments to Reclamation to repay project construction costs, and for project operation and maintenance. There was also an annual charge for their water. In the early years, these expenses took most of what farmers earned. For these reasons, new settlers had replaced more than three-quarters of the original homesteaders by 1927.

By then, the water provided by the irrigation project and the hard work of the settlers had transformed the desert. One writer recalled a visit to the project in 1904:

"I shall never forget my first impressions. It was a journey of two days by team, mostly in dusty sagebrush through a region devoid of human habitation." Thirteen years later the same visitor reported that "the desert has vanished as if by magic; the landscape is completely altered."4

By 1919, there were more than 2,000 farms on over 110,000 acres of green, irrigated project land. The population had grown from a few hundred to 17,000. Railroads carried thousands of carloads of hay, potatoes, and other farm products to distant markets. The value of all the land around the project rose from practically nothing to almost $8 million. Rupert, Burley, and Heyburn, the largest of the six new towns on the project, had their own banks, schools, churches, and newspapers.5

Farming was still a risky business. Even the best-run farms could not avoid droughts and pests that destroyed their crops, and falling prices could reduce profits to nothing. But many settlers, like an anonymous woman writing in New Reclamation Era in 1927, could say they were "satisfied and contented." This woman wrote:

We came to the Minidoka project when it was new and have experienced some of its hardships not the least of which were the poor houses and lack of farm and road improvements. In 1910, sagebrush covered a large part of the Minidoka project. This brush was removed from the land, high places leveled, ditches made, and farming began in earnest. The new ditches often broke and flooded the wrong field. After some time and experience, these things were corrected.

Where it was once barren, bright flowers relieve the monotony of the sagebrush plains. The green of alfalfa and the gold of grain fields against a background of snow-capped mountains make a picture never to be forgotten. After years of work and worry that go with making a home on a new irrigation project, there comes contentment as a reward of well-directed labor."6

Questions for Reading 1

1) What was the Reclamation Act of 1902 intended to accomplish? Do you think the Minidoka Project succeeded in carrying out that intent?

2) Why did Reclamation think Minidoka would be a good location for an irrigation project?

3) List the various elements that made up the Minidoka Project by 1920. When was each of them completed? Do you think the whole irrigation system would work without any single one of these elements? Explain your answers.

4) When did homesteaders begin to file claims on project land? What do you think their lives would have been like before the water came to their farms and homes? How did it change after they had water?

5) What other problems did early settlers encounter? Why do you think those who had no experience with irrigation farming were more likely to abandon their claims? What skills or knowledge do you think would be required of an irrigation farmer that a dry-land farmer wouldn't need to have?

Reading 1 was adapted from "Minidoka Dam, Powerplant and South Side Pump Division" report published by Fraserdesign and Hess Roise and Company (2002) and articles published in the "Reclamation Record" and "New Reclamation Era."

1 Theodore Roosevelt to Ethan Alan Hitchcock, letter, June 17, 1902, found on the Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library website (accessed 1/2/15)

2 The states were Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Texas was not part of the original group because it had no federal lands, but was added in 1906.

3 Alvin C Holmes, Swedish Homesteaders in Idaho on the Minidoka Project (Twin Falls, ID: Ace Printing. 1976), 82.

4C. J. Blanchard, "The Minidoka Project: South Side Unit." Reclamation Record 8 (January 1917), 23; quoted in "Minidoka Dan, Powerplant and South Side Pump Division" (Fraserdesign and Hess Roise, Loveland CO, and Minneapolis, MN, 2002, photocopy--hereafter cited as "Fraserdesign/Hess Roise"), 141.

5 Barry Dibble, "What Has Been Done on the Minidoka Project in Southern Idaho," Reclamation Record 11 (February 1920), 73.

6 "Satisfied--Contented," New Reclamation Era 18 (December 1927), 184-85.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Hydropower at Minidoka

The Reclamation Act of 1902 gave Reclamation one job: to provide water for irrigation. But the water stored behind Reclamation's dams could be used for more than just irrigation. The force of that water could be used to generate electricity. A number of early irrigation projects used electricity to pump water for irrigation. The Minidoka Powerplant produced a lot of power, more than was needed for irrigation pumping. Congress passed a law in 1906 that allowed Reclamation to sell this "surplus" electricity. The money from selling power went back into the Reclamation Fund. That helped Reclamation by giving them more money to build new projects. It also helped the settlers because it was used to pay some of what they owed Reclamation for building and operating their project. But irrigation still came first. Reclamation could only sell power that was not needed for irrigation purposes. The bureau also wasn't allowed to build a powerplant except when electricity was needed for a project.

Reclamation installed five power units in the Minidoka Powerplant between 1908 and 1911. This made surplus power available all year round at Minidoka. Paying customers could use any electricity not needed for pumping during the May-September irrigation season. They could use all of the electricity during the rest of the year.

By 1912, Reclamation had hired Barry Dibble to sell the powerplant's surplus power to the towns and the settlers on the project. He worked to identify ways people could use electricity for more purposes. This was important because Reclamation needed to sell power to keep the plant running all year-round. Dibble didn't think lighting and other ordinary uses would raise enough money to do that. Electric heating seemed to be the answer, because it would use power only during the winter when the full amount was available to sell. Heating with coal was much cheaper, so using electricity for heating was almost unheard of at the time. Reclamation kept the price for electric heating very low to encourage more people to use it, rather than use coal.

Several project towns signed contracts to buy electricity from Reclamation in 1910. They would then sell the power to homes, stores, and factories. Reclamation built transmission lines from the powerplant to the towns. Reclamation also built substations in the towns, which stepped the power down to levels safe for use. Each town then built the distribution network to deliver electricity to their customers. They did not use much electricity at first, but sales to the towns doubled by the end of 1912. That year Reclamation also signed its first contract with a business, the Amalgamated Sugar Company in Burley. In 1914 and 1916, the towns of Rupert and Burley decided to install electrical systems in their new public high schools. By 1920, most stores and houses in towns were using electric power for heating and lighting. By this point, Reclamation called Minidoka the "Electric Project" because power was so widely used in towns.

It took longer to get electricity to the farms. In 1913, Reclamation signed contracts to deliver power to some farms close to the existing transmission lines. But building power lines to farms farther away from existing lines cost too much. Dibble encouraged settlers to form cooperatives to build the new lines, buy power from Reclamation at low rates, and then sell it to their members. He wrote that the farmers were initially "dumbfounded" at the cost to build the lines. But they soon came "to realize that the economies and comforts they can enjoy with electricity are sufficient to warrant the expenses." 1 About half of the 2,500 farms on the Minidoka Project had electricity as of 1926.

Increasing commercial sales was a mixed blessing. Surplus power had been available in 1911. But by 1915, the powerplant could not generate enough power to serve both irrigation pumping and sales. Reclamation needed to add another generating unit to the powerplant, but didn't have the money. In 1921, the Idaho Power Company, a private utility, provided some electricity for project use. In 1923, Reclamation bought Idaho Power Company's powerplants at American Falls, and used that electricity for the project. But it was still not enough power to run the irrigation system and meet the public demand for electricity. In 1927, Reclamation was finally able to add a sixth generating unit to the powerplant, which solved the power shortage for a while. Money from sales of surplus electricity between1910 and 1926 covered the whole cost of adding the sixth unit. In 1942, a seventh and final unit was added to the Minidoka Powerplant. All power from units 6 and 7 was for public sale.

At Minidoka and elsewhere, Reclamation sold surplus power to help pay the cost to build new project dams and canals. But until the late 1920s, Reclamation was not allowed to build powerplants where no project power was needed. It also wasn't allowed to build bigger plants just to generate more electricity to sell. This was because Congress did not want the Federal Government to compete with private electrical utility companies.

This changed when, in the 1920s, residents and politicians from southern California asked Reclamation to build a dam on the lower Colorado River. The river's floods had destroyed towns and farms in southern California. Reclamation was interested in building the dam, but it would cost more than was available from the Reclamation Fund. The solution was to build the dam with powerplants that could generate massive amounts of electricity. That electricity could be sold to cities in California and elsewhere in the southwest. That money would be used to repay the cost to build the dam. After long debate, in 1928 Congress passed the Boulder Canyon Project Act, which directed Reclamation to build Boulder Dam. Boulder Dam was soon renamed Hoover Dam. Congress approved building the dam with massive powerplants. The dam would not do just one job, it would do four jobs: prevent flooding, improve navigation on the lower Colorado, store water for irrigation and other uses, and generate electricity. This made Hoover Dam Reclamation's first "multi-purpose" project. After Hoover Dam was approved, Reclamation's mission was no longer limited to irrigation.

Questions for Reading 2

1) Did the Bureau of Reclamation plan to sell electricity when it began planning the Minidoka Project? Why did it start? Why did it keep on selling power?

2) How was the money that came in from selling surplus power used by Reclamation? How did that help Reclamation? How did it help the settlers?

3) By 1913, irrigation pumping and power sales took up almost all of the electricity generated at the Minidoka Powerplant. What problems do you think might have existed for farmers on the Pumping Division if there wasn't enough power? What problems for people in towns?

4) Why do you think Reclamation's mission was limited to irrigation before the Boulder Canyon Project? What tasks did Hoover Dam have, in addition to irrigation? Why do you think Congress decided to add these new tasks?

Reading 2 was compiled from "Minidoka Dam, Powerplant, and South Side Pump Division" (Fraserdesign and Hess Roise and Co., Loveland, CO, and Minneapolis, MN, 2002) and "Dams, Dynamos, and Development: The Bureau of Reclamation's Power Program and Electrification of the West" (Toni Rae Linenberger and Leah S. Glaser, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, 2002).

1 "Annual [Minidoka] Project History," 1914, quoted in "Minidoka Dan, Powerplant and South Side Pump Division" Fraserdesign and Hess Roise, Loveland CO, and Minneapolis, MN, 2002, photocopy, 141.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: "The Electric Project"

In 1920, less than 2 percent of the nation's farmers had electricity. But on the Minidoka Project, things were different. Reclamation Record and New Reclamation Era were monthly journals published by Reclamation to present stories of the agency's accomplishments. In the Reclamation Record, the agency proudly reprinted an article from the Burley Bulletin, a newspaper published in one of the towns on the Minidoka Project. The article read:

Farming is supposed to be a suntime business that is carried on according to the amount of daylight available. . . . And, of course, it is true that the farmer is dependent to a great extent upon daylight for the completion of his field work.

During the busy season, he must be in the fields at daybreak and must stay there until dark. Before and after these field hours he must feed and water the stock and do a lot of other work at the barn and in the house. Both summer and winter he is pretty likely to do these chores before daylight and after dark. . . . Until the last three or four years the great majority of farm homes still got along with the old kerosene lantern for barn and yard work and with the lamp for the house.

What a difference there is now in the farm homes on the Minidoka Project. Instead of the coal oil lamp lighting just the center of the living room and carried from room to room when light was needed, and cleaned and filled every day, are found handsome electric fixtures. On the living room table is a reading lamp with a shade that softens the bright rays of the electric bulbs, but allows them to reach the farthest corners of the room. Bracket lights on the walls give plenty of extra light whenever it is needed.

In the barn the old lantern is known no more. Electric lamps are strung wherever they will do the most good.1

Another Reclamation Record article from the same year provided more detail:

Electricity for lighting purposes is always used wherever service has been obtained. In addition, the farmer, and especially the farmer's wife, are using electricity for a great diversity of purposes. . . The electric iron is the most popular of all appliances, and the records show that over 75 percent of the rural consumers use the iron. The washing machine is perhaps a second choice and, in spite of their high prices, over one-third of the farmers' wives are washing with electric washing machines. Electric cooking appliances are just beginning to come into popular use on the rural lines. . . A large increase in the cooking load is expected during the coming year.

Vacuum cleaners, electric incubators and brooders, and many other labor-saving devices are coming into more general use. Considerable energy was used during the past spring in homemade brooders, which were equipped in many cases with a carbon-filament lamp to supply the necessary amount of heat to keep the little chicks warm. Many a farmer now has a motor . . . which drives a pump, cream separator, grindstone, food grinder, and numerous other appliances for labor saving.

Half of the farmers have large yard lights on poles. With all these burning at night it is difficult to tell from a distance where town begins and country ends.2

An article in the New Reclamation Era reported that about half of the 2,500 farms on the project had electricity in 1926. By this time, the list of electric appliances had grown:

Many [housewives] also use electric hot plates, grilles, toasters, waffle irons, percolators, curling irons, warming pads, ranges, churns, sewing machines, and house fans.3

The star of the "Electric Project" was Rupert's "Electric High School," built in 1914.4 The Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah) described its features in a long article entitled "Electric Devices Reign Supreme at the New High School":

Rupert, Idaho, is at the present time decidedly in the limelight because of its new and model "electric high school." This building has the distinction to be the first large building in the world to be heated entirely by electricity. An electric ten-horsepower motor supplies all the power needed for driving the lathes, saws, etc., in the manual training department. An electric water heater supplies hot water for the domestic science rooms. In the domestic science room, each girl of a class of 20 has her individual disk stove.5 This room is also provided with electric flatirons and will have an electric range and electric equipment for the adjoining cafeteria lunchroom.

The building is supplied with a fine system of electric lights throughout, the auditorium and stage having lights and switchboard control similar to those of the better theaters. This room is also equipped for using a moving picture machine. The lighting, as well as much of the other equipment, has been planned with the view of making this building a "model community center."

The system of schools housed in Rupert's fine school buildings is just as modern as the buildings themselves. The district is a large consolidated district. Modern enclosed school wagons transport to and from school all children outside a reasonable walking distance and within a reasonable driving distance. The high school is an accredited four- year high school. The high school, with eight teachers, has a fine band, orchestra, glee clubs, and athletic teams. When it is remembered that eight years ago this part of the great Snake River valley was a sagebrush desert and that less than four years ago the Rupert school system consisted of part of one building, the transformation is wonderful.6

Questions for Reading 3

1) How did farm families on the Minidoka Project use electricity?

2) Why do you think a newspaper in Salt Lake City, Utah, would publish a long article on a high school in Rupert, almost 200 miles away? What about it being "electric" was so interesting?

3) Reclamation reported that project farm families at Minidoka were buying electrical appliances as fast as they could afford them in 1920. Why do you think that might have been the case? Consider how having electric appliances changed a farm wife's life. How would those tasks be completed without electric appliances?

4) In what ways was Rupert's school "electric"? Look around your classroom and see how electricity is used there. What would your classroom be like without electricity?

5) School prepares students for the future. What kind of future did the "electric high school" prepare its students for?

1The excerpt is quoted from "Electricity and Home Building--The Minidoka Electric Project a Shining Example," Reclamation Record 11 (April 1920), 183, an article originally published in the Burley Bulletin, a newspaper published in Burley, Idaho.

2 Howard H. Douglas, "Use of Electricity in Rural Communities on the Minidoka Project," Reclamation Record 11 (September 1920), 500-501.

3 "Minidoka Project Homes Enjoy Electrical Aids," New Reclamation Era 17 (July, 1926), 119.

4 Burley built its own "Electric High School" in 1916.

5 Disk stoves use a solid metal disk for the burner. Some modern hot plates still work like that.

6 Salt Lake Tribune, March 29, 1914, 11.

Visual Evidence

Illustration 1: Schematic Drawing of a Hydroelectric Generator.

(Illustration courtesy of the Bureau of Reclamation)

All generating units have four main parts: a turbine, a rotor (a series of magnets), a shaft connecting the turbine to the rotor, and a stator (a coil of copper wire). Water flows down from the reservoir and rushes toward the turbine blades. The force of the falling water spins the blades when it hits, which turn the shaft connected to the rotor above. The rotor spins. This creates a magnetic field as its magnets sweep past the coils of copper wire in the stator. This creates an electric current.

In the powerplant powerhouse, the current travels from the generator through wires, out to long distance power lines, and into the homes, schools, and businesses of the electricity users.

Questions for Illustration 1

1) What are the main parts of a hydroelectric power generator? What parts aren't shown in the illustration? (Refer to Reading 1 if necessary)

2) What is hydroelectric power? Explain in your own words.

3) What role does gravity play in producing electricity? What other natural force can you find in the generator?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Aerial View of Minidoka Dam and Powerplant, 2015.

You are looking east toward the Minidoka Dam and Powerplant. The dam on the south end is 86 feet high and 736 feet long. The 2,400-foot-long concrete spillway stretches out in a zig-zag, south to north. The historic, multistory 1909 powerplant can be seen at the north end of the dam, between the river and the reservoir. Water flows from the reservoir through the powerplant generators, and then into the river. The distance the water falls between the reservoir and river determines how much power the plant can generate.

The two main project canals are also visible. The Main North Side Canal appears vertical in the bottom left part of the image. The Main South Side Canal appears horizontal near the upper right edge.

Questions for Photo 1

1) Identify the Minidoka Dam, powerplant building, canals, and the reservoir in Photo 1. What evidence in the photo helped you find them?

2) How does the level of the water in the reservoir compare with the level of the water after it leaves the powerplant? How does this difference relate to the production of electricity in the powerplant?

3) Assess the length of the dam and spillway. Sometimes the best way to get a sense of the size of a large structure is to compare it to something you know. A football field is 360 feet long. How many fields long is the dam?

4) How did the Reclamation Act change the landscape of the West? What evidence of the effects of the Minidoka Project do you see in this photo?Visual Evidence

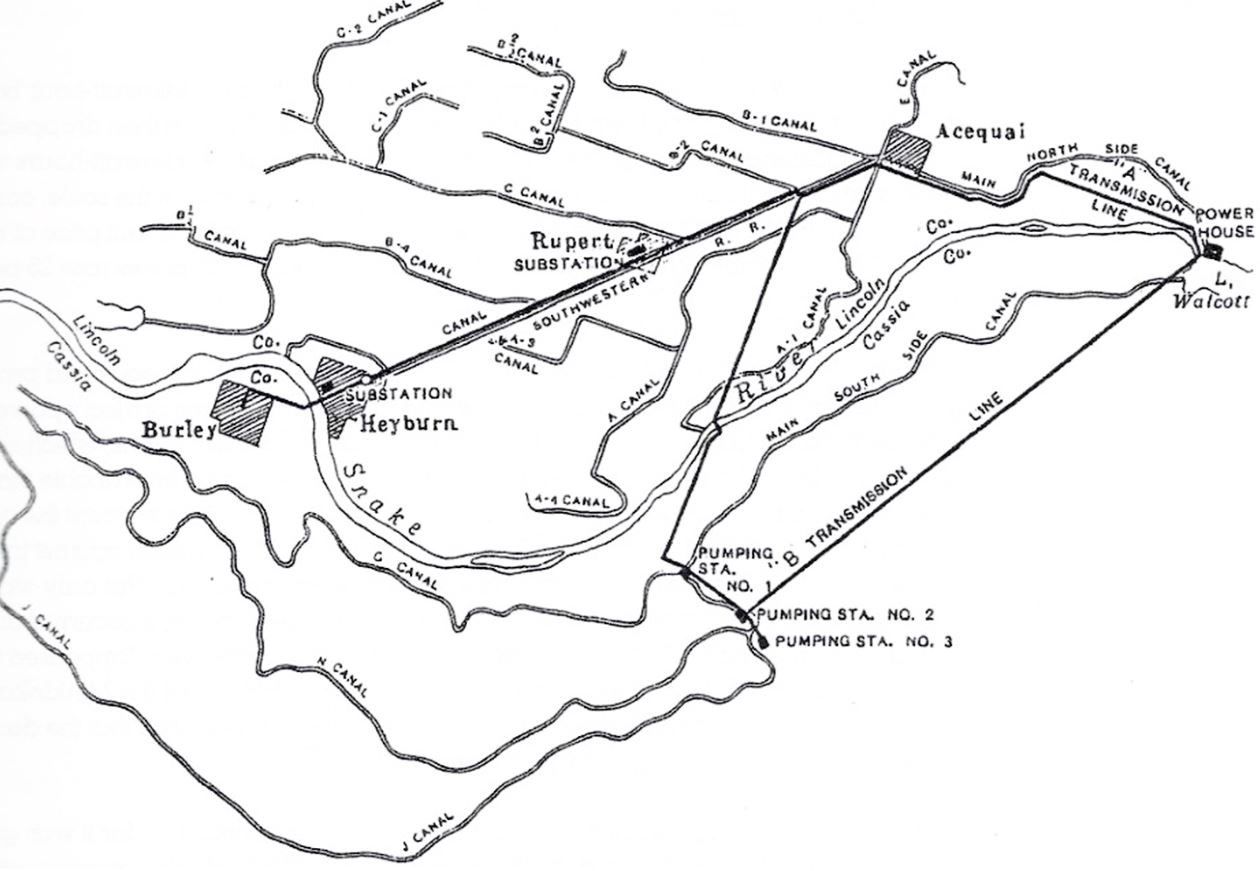

Illustration 2: Minidoka Project in 1911, showing Main Transmission Lines.

(Originally published in Electrical World, Dec. 30, 1911.)

Questions for Illustration 2

1) Locate the Snake River in Illustration 2. Then find Minidoka Powerplant (called 'Power House' on this drawing). Trace the course of Transmission Line A, which begins at the powerplant and generally follows the Main North Side Canal and the Southwestern Railroad line. Where does it go? What purpose do you think it served? Why were the substations located in the towns? (Refer to Reading 2 if necessary)

2) Trace the course of Transmission Line B. Where does it go? What purpose did it serve? (Refer to Reading 1 if necessary)

3) Look for the Pumping Lift Stations. Where are they in relation to the transmission line and the canals? Why does this relationship exist? (Refer to Reading 1 if necessary)

4) Can you find any evidence of electricity going to farmers living outside the towns on this map? Why do you think that might be the case? (Refer to Reading 2 if necessary)Visual Evidence

Photo 2: Homesteader's Home, Minidoka Project, ca. 1910.

(Bureau of Reclamation)

Questions for Photo 2

1) Divide this photo into sections and make a list of everything you see in each section. How many buildings and structures did you find? What purpose do you think they served? What kind of place is this? What buildings can you find in Photo 2 and what do you think they were used for?

2) What evidence of agriculture can you find? Do you think this place receives much rain? Do you think this farm was receiving irrigation water? What evidence can you find in the photo to help you answer that question?

3) Was this homestead using electricity? How can you tell?

4) Do you think this homestead was typical? Why or why not? (Refer to Reading 1 if necessary)

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: Interior of the Minidoka Powerplant, 1911.

(Bureau of Reclamation)

Photo 3 shows the five original generators installed between 1908 and 1911. The five large machines on the balcony are transformers. Cables carry electricity from the generators to the transformers. The heavy, shielded cables coming out of the tops of the transformers and leading out of the building carry electricity to the transmission lines.

Questions for Photo 3

1) Compare Photo 3 with Illustration 1. What part of the powerplant does the photo show? What is located beneath the floor, in the lower level you cannot see in this picture? How does that relate to the production of electricity?

2) How would you describe the generators? How big are they? How can you tell?

3) How many generators do you see in this photo? Why did Reclamation leave room to add more generators? Did they add any later? (Refer to Reading 2 if necessary.)

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Canal and Transmission Lines, ca. 1915.

(Bureau of Reclamation; photographer unknown)

Questions for Photo 4

1) Compare this photo with Illustration 2. Where might the photo have been taken? What canal might this be? Why do you think so?

2) How many groups of buildings can you identify in this photo? Do you think each group is a farm? Do you think this would be a good location for a farm? Why or why not?

3) How did Reclamation change this landscape when they brought the irrigation water to the land?

4) What does this scene reveal about life in the early 20th century? How is it "modern" compared to our lives today? How does it look "old-fashioned"? Do you think the people who lived on these farms in 1920 thought their life was "modern" or "old-fashioned?" Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Domestic Science Class, Rupert High School, ca. 1914.

(Bureau of Reclamation)

This photo shows 16 high school girls and their teacher in what would later be called a "home economics" class.

Questions for Photo 5

1) What evidence of electricity can you find in this classroom? Where do they get their light? Compare what you see with the description in Reading 3 of electrical conveniences and appliances at the school.

2) Look around your classroom and compare electrical use in the photo to use in today's classrooms. What is the same, and what is different?

3) Most of the homes on the Minidoka Project did not have electric stoves in 1914. Why do you think the school taught girls how to use electric stoves if most did not have them at home?

4) In the first half of the 20th century, high school girls took "domestic science" or "home economics" classes like the one shown here. Boys took classes called "manual training" or "shop," where they learned how to work with metal and wood. What does the difference in how boys and girls were trained tell us about what the school expected for them in the future?

Putting It All Together

By studying "'The Electric Project': The Minidoka Project and Powerplant" students have learned how the Bureau of Reclamation's Minidoka Project used electricity for irrigation purposes. They also learned how the Bureau came to provide electricity to project farms and small towns in the early 20th century, transforming the lives of the settlers. They have also discovered that the "Electric Project" is an example of how Reclamation's mission expanded from providing water for irrigation, to providing both water and power for farms and cities.

Activity 1: Centuries of Change: How Everyday Life Has Changed Due to Electricity.

Have your class study and contrast the ways everyday tasks were completed in the late 19th century, early 20th century, and today, using the technology available to them in each period. Students should ultimately consider the ways and extent to which access to electricity, and labor saving devices and conveniences, altered how Americans live.

First, have students keep a daily diary of their use of electricity. They should note each time they use an electrically operated item to make life more convenient or to complete a task (examples: use electric lights, make breakfast, or for entertainment). They should note the device and purpose of use.

Next, bring the class together to compile a list of their individual observations. After compiling the list, review the Minidoka Project lesson plan readings and other available materials. A book, available on the internet, that would be useful to understand late 19th century life is From Attic to Cellar or Housekeeping Made Easy, written by Elizabeth Holt and published in 1892.

Have students identify, using Holt, how daily activities and tasks were accomplished in the late 19th century. Using Minidoka Project readings, have students identify how those activities and tasks were accomplished by 1920.

Then have students compare the list of activities and tasks they compiled to identify how these tasks were accomplished by the early 21st century. This might be accomplished as an individual homework assignment or in class as group assignments.

Then, in class discussion, compare and discuss change over the last 150 years. Ask your students to consider where we will be in another 100 years. Ask them to use what they have learned in this activity to reach those conclusions.

Activity 2: Public vs. Private Power

Reclamation and a private utility company, Idaho Power Company, worked together to help solve power shortages on the Minidoka Project in the early 1920s. Each benefited from the bargain. But this was not always the case. A national debate about public versus private power had begun early in the 20th century. The debate grew when Reclamation began planning the Boulder Canyon Project (Hoover Dam) in the 1920s. Progressives and other advocates of public power thought electricity should be treated as a necessary service, like water, generated and provided to consumers by non-profit federal, state, and municipal agencies. They also hoped competition between public and private energy providers might lead to lower rates. Others thought having the government involved in providing electricity was inherently inefficient, and some felt it sounded a lot like socialism. Some thought electricity was just another commodity, and so should be produced and sold by profit-making private companies. People owning or holding stock in private power companies feared they would lose business and profits. Small Bureau of Reclamation powerplants like at Minidoka caused little public controversy, because the electricity generated was primarily for project use, and sales were not large enough to threaten private utility markets. But Hoover Dam would produce huge amounts of power for commercial sale, competing with private enterprise. Congress approved construction of Hoover Dam only after long debate between public and private power advocates, both in Congress and in the press.

Ask each student to write a report comparing and contrasting the Minidoka Project with the Boulder Canyon Project. Have them describe the both arguments vocalized in the early 20th century that were for and against public utility projects. There are many resources online students can discover to help research that topic, like this page at PBS.org. They will find information about the location, approval date, purpose, size, planned generating capacity, states involved, and cities/towns served for the Minidoka Project in the readings. Ask the students to present their reports to the class. Finally, ask the whole class to discuss why they think reactions to the two projects were so different.

Activity 3: How do you get your electricity?

When you ask most people how they get their electricity, the answer is "I turn on the switch." Perhaps a better question would be "Where does it start?" Ask students to investigate the electric power system in their community. Does the money their parents pay for electricity go to a public utility or to a private company? Is water the source of power to generate electricity for their community? If not, what is and why? When was electricity first available in their area? What buildings, structures, or systems exist to produce the power and to deliver it to businesses, homes, and other users? Where are they? (Some may not be recognizable as power related facilities, or are so much taken for granted that no one notices them.) Who built them? Who checks them to be sure they are operating safely? Who is responsible for keeping them in good working condition?

Some of these power-related facilities may be impressive historic structures. Some may have been sources of great local pride when they were first created. Others may be strictly utilitarian structures or even ugly, but may still be important parts of the community's history. Have students work in groups to identify and research these facilities. Ask them to determine whether any of them are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. If they are, obtain copies of the National Register documentation to use as part of their research. Ask the groups to work together to create their choice of an exhibit, podcast, online brochure or tour, short documentary, article for the local newspaper or historical society newsletter, driving or walking tour, or other interpretive product. Select a day when the students can present their findings to the rest of the class, or even at a school assembly. Offer the interpretive materials to the local historical society, library, and/or chamber of commerce. If none of the facilities is officially recognized for its historic significance, the class may want to initiate the nomination process for obtaining local or state designation or for listing in the National Register.

Research may reveal that some structures have suffered from deferred maintenance. Have the class consider what dangers may exist if a power facility can no longer operate safely or efficiently. The class might want to consider taking action to call this potential problem to the attention of their local government.

Students have learned how the Bureau of Reclamation's Minidoka Project came to provide electric power to the project's farms and small towns in the early twentieth century. They have also discovered that this "Electric Project" was a step towards a major expansion of Reclamation's mission. Students interested in learning more will find many useful sources on the Internet. Some sources are:

Bureau of Reclamation Resources

The Bureau of Reclamation's Mid-Pacific Region has developed a website that contains educational materials that use an idealized farm to explain the three basic irrigation methods, how each one works, when it works best, and what the costs and benefits are. The site also includes lesson plans.

U.S. Energy Information Administration

The EIA Energy Kids website provides teachers and students with information on energy use in the United States. This hydropower resource introduces the history, forms, and environmental impacts of hydroelectricity. Students may use this and other site resources to explore many types, uses, and considerations of energy use.

U.S. Geological Survey Water Science School

The U.S. Geological Survey has created a Water Science for Schools website that answers every question you are likely to have about water, from the water cycle to water quality to how wet your state is. The site includes Teacher Resources.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

The website of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has a link to a chapter of a book that provides simple explanations of how an irrigation system works, with graphics. Other chapters in the same book, published by the FAO in 1985, cover soils, topography, etc.

Learn Engineering

This engineering science education and outreach website presents "people the so called 'tough engineering concepts' in a logical and simple way." The website covers electrical, mechanical, and civil engineering topics and uses video, engaging graphics, and plain-language articles to teach engineering.