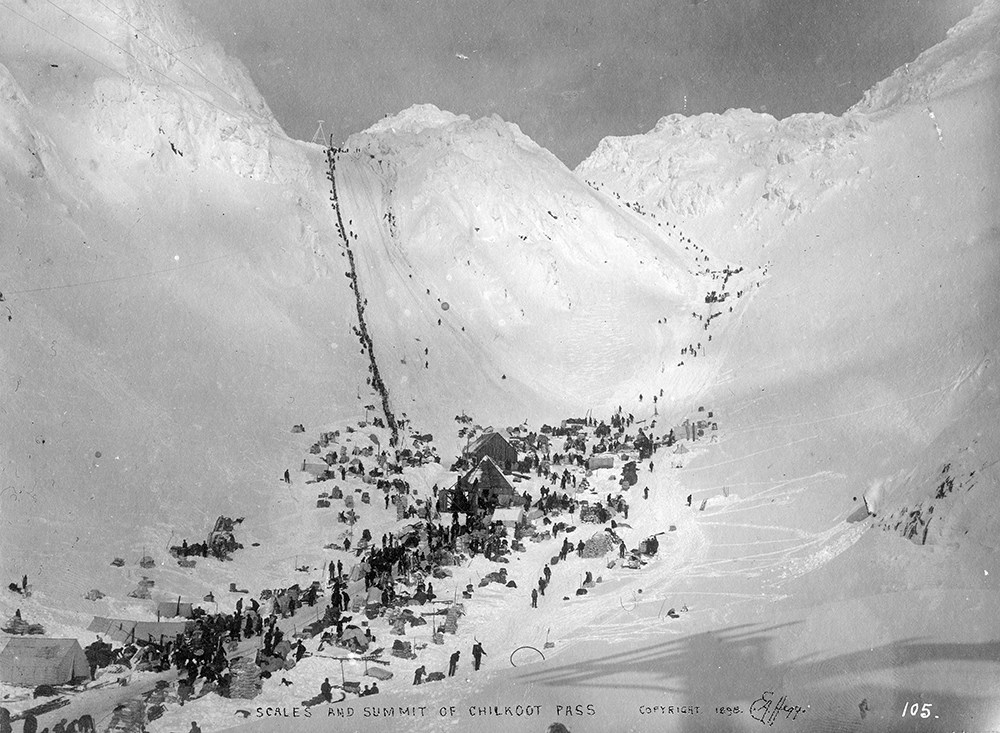

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library SS-32-10566. The elevation at the Scales is approximately 2750 feet, a thousand feet or more above timber line. During the winter, snow can build up to a depth of ten feet or more here. Snow has fallen every month of the year, and the winter snow pack sometimes lingers into August. Wind, fog, and rain are also frequent in this area. Fog in particular reduces the area's visibility to thirty feet or less. Because of the great snow pack, even a sunny day can be dangerous. Several historic photographs show travelers wearing crude sun goggles. In some accounts stampeders suffered from snow blindness. For these reasons, the site was hardly an attractive place to camp or cache goods. Nevertheless, thousands did so during the epic winter of 1897-98. Pre-Klondike Gold Rush The Scales had been a well-known site before the Klondike Gold Rush began. Alaska Natives passed through on their way to and from the Canadian Interior. Later, Ben Moore and the Ed Lung-Bill Stacey party were among those who cached their goods here. Most early prospectors, however, did not linger in the area. They typically camped at Sheep Camp or Stone House. From there they shuttled their goods forward to the summit of Chilkoot Pass. Then they moved their base camp all the way to Lake Lindeman. Once camp was moved they ferried their load from the pass down to their new base camp. Traffic over Chilkoot Pass increased as news of gold discoveries began in the 1880s and 90s. Shortly after the rush to Circle City began, improvements to the pass began. An entrepreneur named Peter Peterson first installed a crude rope tramway up from the Scales up Chilkoot Pass. After testing his tramway in Juneau, he installed it on the pass in the spring of 1894. The following year, he again established an operation, this time with the help of Ben Moore. J. T. Field, an owner of trading posts in Dyea and Juneau, also sponsored the scheme. The tramway system consisted of a series of ten sleds attached to ropes. It featured heavy poles dug into the snow. Loads were shunted up and down the pass on an endless rope. The system was powered by loading the sleds at the top with snow. This tram probably operated over the so called Peterson Route. This route went east of the present day trail. It was a longer, more roundabout alternative to the climb directly over Chilkoot Pass. Before the winter of 1896-97, most stampeders preferred it because of its more gradual ascent. The success of Peterson's scheme is debatable. Moore claimed that the system proved impractical and was soon abandoned. Juneau newspapers, however, reported that the tram was successful. Peterson remained in the area most of the spring season. He carried enough freight to anger the local Tlingits. They claimed that the tram had "forever put an end to the packing from Dyea to Lake Lindeman which formerly was a source of considerable revenue." Shortly afterwards, Peterson left the area and headed down to Yes Bay, south of Wrangell. But in the spring of 1896, he opened an improved tramway operation over Chilkoot Pass.

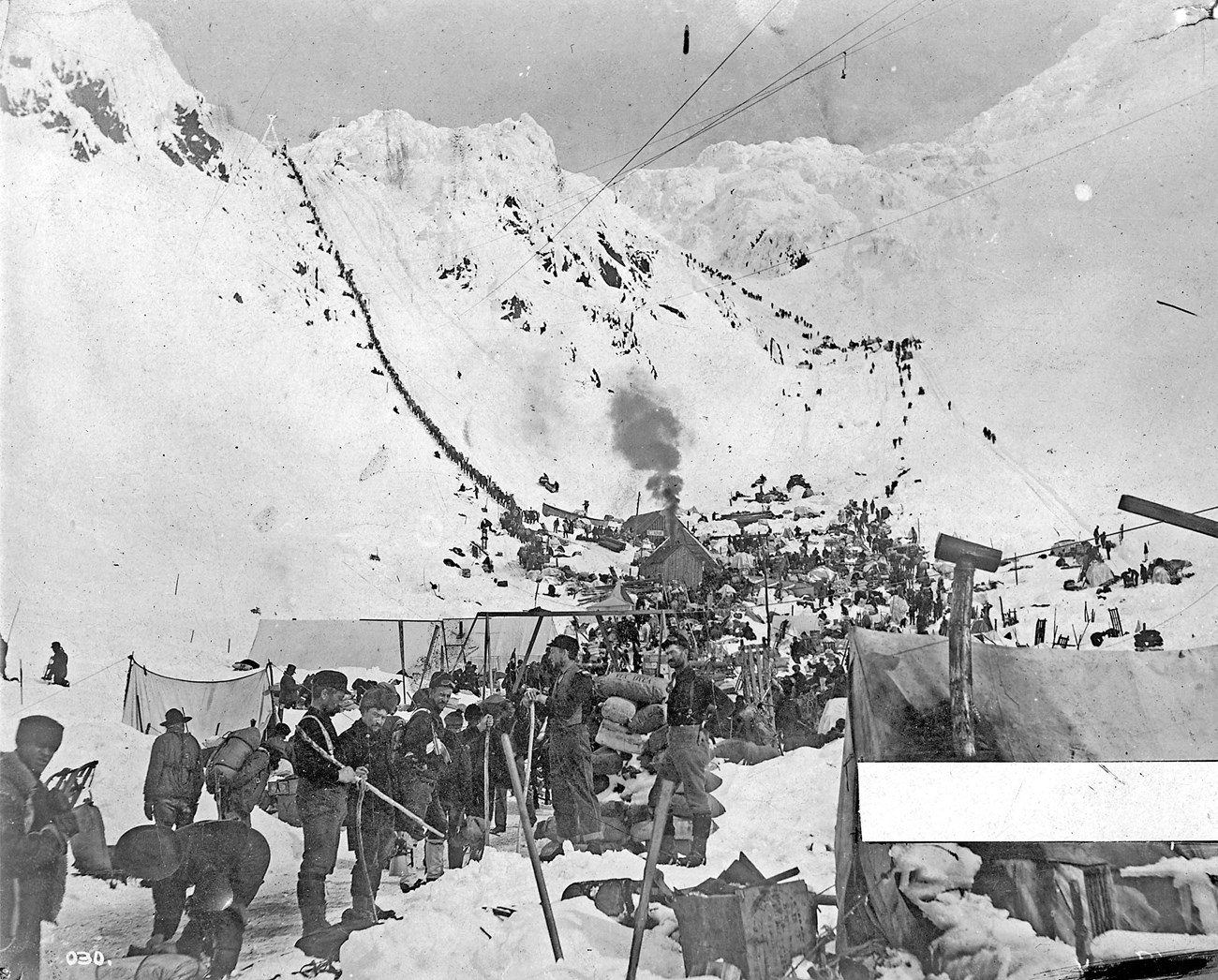

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55832a. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. Klondike Gold RushIn the spring of 1897, the first wave of Klondike stampeders headed north. With them, the demand for hauling goods over Chilkoot Pass increased. In anticipation, sourdough Archie Burns had claimed the summit area as a trading and manufacturing site the previous fall. Several months later, he began operating a horse drawn whim which pulled sleds from the Scales to the summit, directly up Chilkoot Pass. J. H. E. Secretan, who passed by in April 1897, noted that the lift was powered by "two wretched horses" plodding around in a circle, "winding up sleigh loads of supplies and passengers at one and one half cents per pound." Remnants of a whim still lie on top of Chilkoot Pass.Soon after news of the gold rush broke, the Scales began to witness increased activity. For perhaps the first time, the site became a summer camping area. In mid September the Scales hosted "some score of tents and huge piles of baggage." Even in summer, it was described as …one of the most wretched spots on the trail; there is no wood nearer than four miles, and that is poor. The wind blows cold, and everybody and everything is saturated. The tents are held to the earth by rock on the guy ropes.

Other parties camping there that month had a similarly inhospitable experience.Before August 1897, passers by called the site "the foot of the summit," "the foot of the pass," or "the foot of Chilcoot Summit." People heading north in mid summer, however, began to call the area "the Scales." By late September the place name was described without reference to quotation marks. As Alfred Daly and others have stated, the area got its name because "there is a tradition that some time or other there was a pair of scales where they weighed out the packs for the packers to take over the summit." Later, during the winter and spring of 1897 98, a large "steelyard scales" existed at the site. The namesake scales may have dated from Archie Burns' operation during the spring of 1897, or from scales the Indians used that same spring. The Scales probably remained a tent camp through the fall of 1897. But in December, a semblance of permanence began when Archie Burns returned to the Scales. He may have started up his horse powered tram again, and he installed a steam powered hoisting drum, followed soon afterwards by a gasoline powered tramway. Burns installed both machines on or near the top of the pass. His office and storage area were at the Scales. At about the same time that Burns arrived, the Dyea Klondike Transportation (DKT) Company moved into the area. The Company built a powerhouse at the south end of the Scales. They constructed a simple two bucket tramway from there to the top of the pass. The tramway lines hung well above the Scales area. The first DKT tramway tower was located at the false summit. It is not known when construction of the powerhouse began, but the powerhouse (and tramway) were operating by March 14, 1898. Several other tramways were soon put into operation. One was Peterson's tram, which had previously operated from the spring of 1895 and 1896. Peterson, however, did not operate it in 1898. He leased it to J. F. Hielscher in mid February. Hielscher operated the tram over the Peterson Route that spring. Two other tramways built towers through the area, but neither operation had an office or powerhouse here. …the horrible sight of many dead horses drew my attention more than the beauty of the landscape. I could distinctly see a mass of dead horses lying in an enclosure where they had been led and shot. I could clearly make out nine, but many more were around the foot of the pass.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Hooper Collection, KLGO 0004.005.001.0005 38. In February, two entrepreneurs carved a series of three foot wide steps into the slope below the false summit. They strung a guide rope along the right side of the pathway, and carved out a bench every twenty steps as a rest area. Midway up the slope, they constructed two wooden archways over the route. These may have been designed to keep the tramway buckets from striking the stampeders. They were in place for only a short time. The operators charged a fee for their improvements. This fee allowed unlimited use of the steps for one day. Estimates vary widely on the length of time required to ascend the slope. Edward Banon, who climbed it in March, claimed the trip took only 30 minutes. Historian Pierre Berton stated that during the height of the rush the trip took six hours. This meant that most stampeders could only make one trip up the slope each day. The number of steps has been variously estimated at 1378, 1500, and "between 1100 and 1200." These so called "Golden Stairs" remained until the snow melted in June. Post Gold RushWith the decreasing stampeders, the Scales and other Chilkoot communities faded quickly away. The stampeders and most of the merchants moved north. The surface tramways were forced to close down when the snow melted. The DKT Company ceased operations in the summer of 1898. Soon, all that remained at the site were the remains of a few wooden buildings and tent frames. For awhile the camp may have been entirely deserted, but a minor revival took place during the winter of 1898-99. One of Archie Burns' tramways, and possibly two restaurants, operated for some or all of the winter.The completion of the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad to the summit of White Pass effectively eliminated traffic over the Chilkoot Trail. In early 1900, crews came into the area to disassemble portions of all three aerial tramways. That fall, Archie Burns also visited the site to remove his own tramway equipment. Based on what remains today in the area, however, he was only partially successful in his mission.

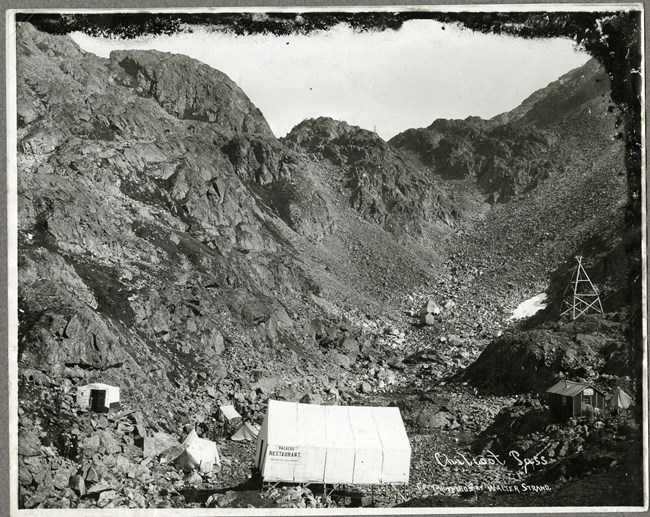

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59644. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. “A Sea of Debris”Since 1900, the Scales area has continued to decay. By September 1906, only two buildings still stood at the site. They were still standing five years later. A post gold rush photo shows one of the two remaining buildings was the former Scales restaurant. The use of the other building is unknown.By the time the Chilkoot Trail opened for recreation use in the 1960s there were no standing structures. The sixty intervening years had reduced the site to a large, scattered sea of debris. J. R. Lotz, who passed through in the summer of 1963, noted that the area had been "swept away by slides". Five years later, a guide book noted a large number of artifacts. These included "horseshoes, muleshoes, spiked creepers, remnants of harness, old cable, galvanized telegraph wire, utensils, kerosene lamps, axes, shovels, tram parts and where protected, items of discarded clothing." In 1973 Archie Satterfield advised that the site contained "evidence of cabins, machinery, cooking utensils, tools, sleds, clothing and other debris slowly rotting away." Since then, many items have been lost to weathering, rock slides, theft, and vandalism. Reports from NPS rangers say that artifact removal and burning of historic wood has been a continuing problem. Reports generated from archeological field work noted the ongoing destruction of the resources. Despite the loss of artifacts over the years, many remnants of the gold rush remain at the Scales. A 1979 archeological survey team located two structural scatters, a boiler, and "hundreds of domestic and industrial artifacts ... seen among the rocks." These included cable, wire, pots, pans, shoes, clothes, pulleys, bandings, tin cans, ceramics, wheels, rod, pipe, shovels, basins and other materials. In 1982-83 archeological survy teams inventoried historic materials at the Scales. These surveys located, identified, and catalogued hundreds of artifacts. Today this area is closed to camping to protect the gold rush remnants. Each summer several thousand backpackers pass through this area. Most use the area like the stampeders, as a resting spot before climbing up to the pass.

Left image

Right image

|

Last updated: January 28, 2020