Transcript

Encompassing over 800 square miles in the Southern Appalachian Mountains, no other area of equal size in a temperate climate can match Great Smoky Mountains National Park in number and variety of animals, plants, fungi, and other organisms. It is the most biologically diverse National Park in the United States. Located within the Appalachian Mountain chain, the park became a refuge for many species of plants and animals that were displaced from their northern homes by changing climate conditions during the last ice age. The Smokies are one of the oldest mountain ranges in the world, formed perhaps 200-300 million years ago. Elevations in the park range from 850 to over 6,000 feet; a change in elevation that mimics the climate and habitat variations found from Georgia to Maine. Plants and animals common in the southern US thrive in the lowlands. Species common in the northern states find suitable habitats at the higher elevations. The crest of the Great Smokies runs in an unbroken chain of peaks for over 36 miles. The park's abundant rainfall and high summertime humidity provide excellent growing conditions.

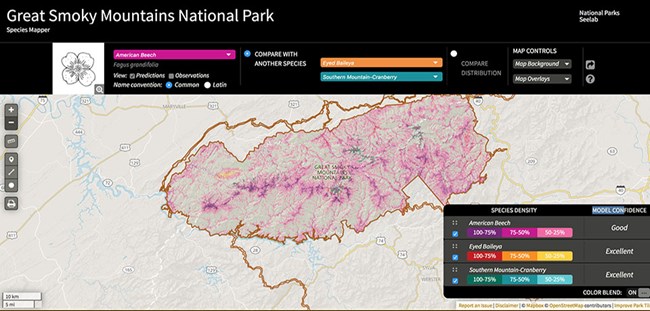

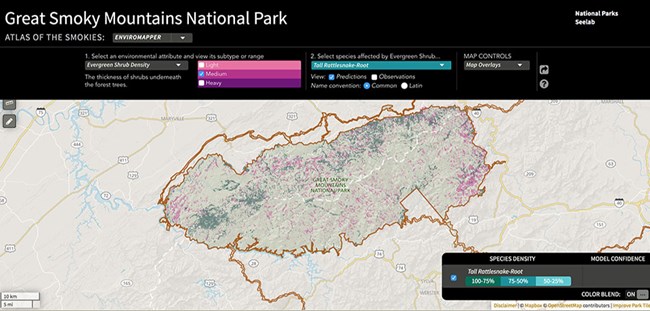

Weather and an array of habitat conditions supports a wide range of living things. Over 19,000 species have been documented in the park, including more than 100 species of native trees, over 1,500 flowering plant species, more than 200 species of birds, and over 9,000 different species of insects. With such biodiversity, how can park visitors and researchers learn where to find plants, animals and other organisms in the park? The park has partnered with the University of Tennessee to use analysis modeling and data visualization to predict the locations of the park’s species. Predictions are based on observations of species. Species have been observed and documented in the park for over a hundred years and new discoveries are being made all the time. The model analyzes the locations of these observations as well as the characteristics of the habitat such as slope, geology, elevation, forest type, temperature, and sun exposure. The results are predictions of where the species might likely be found in the park. Understanding where species are in the park is critical to their conservation. As the Park continues to gather data, the model will become more accurate and we will be able to add more species. Only when we understand the park’s biodiversity can we truly protect it.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

This video describes the the diversity of life in the Smokies and introduces viewers to the applications the park has created with the University of Tennessee.

Great Smoky Mountains is the most biodiverse park in the National Park system. Biological diversity, or ‘biodiversity’, means the number and variety of different types of animals, plants, fungi, and other organisms in a location or habitat. Encompassing over 800 square miles in the Southern Appalachian Mountains, no other area of equal size in a temperate climate can match the park's amazing diversity. Over 19,000 species have been documented in the park and scientists believe an additional 80,000-100,000 species may live here. In partnership with the University of Tennessee, Great Smoky Mountains National Park has created a series of tools to help people engage with the park’s natural resources.

NPS

NPS

Quen Eastridge In 1998, the Smokies began a park-wide biological inventory of all life forms; this project is referred to as an All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory or ATBI. The goal of an ATBI is to determine what species live in the park, their distribution, and their ecological community. Scientists have discovered nearly 10,000 species that were not previously known from the park, and many of these (~1000) had never been seen anywhere in the world before; they were new to science. The extraordinary diversity of this park led to the park’s designation as a United Nations World Heritage Site and International Biosphere Reserve. The ATBI in the Smokies is coordinated by our non-profit partner Discover Life in America, or DLIA. Together, the park and DLIA have made tremendous progress, and the ATBI has grown to become the largest sustained natural history inventory in the United States, and one of the largest in the world.

How does the modeling work? The park has partnered with the University of Tennessee to create tools to allow visitors to explore the environment and the species in the park. The tools use analytical models to predict where each species "live" in the park. These predictions are based on observations made during ongoing resource monitoring as well as research studies conducted by scientists from all over the world. The model analyzes the location of observations in tandem with the characteristics of the habitat, including terrain, slope, forests type, geology, elevation, temperature, and sun exposure. Through our wealth of species observation data as well as what we known about the park's environment, the computer model is able to predict where a species is likely to live in the park. As the datasets continues to grow, these predictions will continue to become better and better. Why such a wondrous diversity? In terms of weather, the park's abundant rainfall and high summertime humidity provide excellent growing conditions. In the Smokies, the average annual rainfall varies from approximately 55 inches in the valleys to over 85 inches on some peaks. The relative humidity in the park during the growing season is about twice that of the Rocky Mountain region. Extensive work and research is being done to preserve the biodiversity of the Smokies. Environmental factors such as air quality,water quality, and non-native species are monitored and fires are used as a tool to maintain healthy ecosystems. Recommended Reading

Great Smoky Mountains National Park: The Range of Life |

Last updated: December 22, 2022