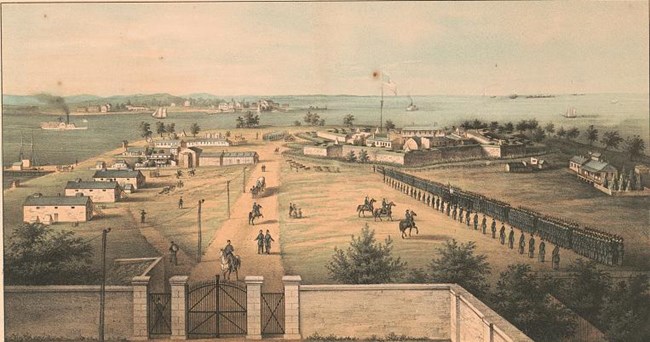

NPS/Tim Ervin In the years following the Battle of Baltimore, Fort McHenry remained an active military fort. The fort went through many upgrades such as building additions, improved bomb proofs, creation of an outer battery, and the installation of larger seacoast Columbiad guns. Following Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, Southern slave-owning states began to secede from the United States of America starting with South Carolina. In no place was there a greater rise in tensions than the state of Maryland. Because of Maryland’s role as a border state, Fort McHenry would once again serve an important purpose in a time of war.

NPS Rising Tensions and a Firm ResponseIn April of 1861 southern batteries opened fire on U.S. troops at Fort Sumter and in response President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to help put down the rebellion. The call for troops also incensed Maryland secessionists and tensions rose in Baltimore as the city became a powder keg ready to explode. The crisis came to ahead when on April 19, 1861 the 6th Massachusetts regiment marched through the city from the President Street Rail Station to the Camden Station to travel to Washington D.C. The sight of federal troops marching through the city angered secessionists who began attacking the troops starting a riot in which 4 soldiers and 12 civilians were killed, and 36 soldiers and hundreds of civilians were wounded.

NPS The American BastilleFort McHenry was never attacked during the Civil War, and any further uprisings after the Pratt Street Riots were deterred. The fort’s most important role became what no one could have predicted: that of a prison. The fort’s first major influx of prisoners of war came in the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam (1862), fought in the western part of Maryland. Fort McHenry soon became a much-needed space to house captured Confederate soldiers who were eventually transferred to larger facilities. Fort McHenry’s new role as a transition site for POWs was established and just about any Confederate POWs captured in the eastern theater of war would pass through the site at some point. The largest surge of captured Confederates came following the Battle of Gettysburg (1863) in which 6,957 prisoners were held at the fort at one time.

|

Last updated: July 16, 2025